The Hippocratic Oath: Are We Hurting Ourselves and Each Other?

August 15, 2023

Related Articles

-

Echocardiographic Estimation of Left Atrial Pressure in Atrial Fibrillation Patients

-

Philadelphia Jury Awards $6.8M After Hospital Fails to Find Stomach Perforation

-

Pennsylvania Court Affirms $8 Million Verdict for Failure To Repair Uterine Artery

-

Older Physicians May Need Attention to Ensure Patient Safety

-

Documentation Huddles Improve Quality and Safety

AUTHORS

Balaj Rai, MD, Kettering Medical Center, Kettering, OH

Zachary Gilbert, MD, Kettering Medical Center, Kettering, OH

Charles Brenden Croughan, MD, Kettering Medical Center, Kettering, OH

Harvey Hahn, MD, Kettering Medical Center, Kettering, OH

PEER REVIEWER

Ellen Feldman, MD, Altru Health System, Grand Forks, ND

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

- Healthcare workers have a higher prevalence of burnout compared to the rest of the population, with higher levels of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization.

- The symptoms of burnout can be categorized broadly into a five-stage model. Burnout occurs in stage 4, causing self-doubt, social isolation, pessimism, escapist activities, and physical symptoms.

- The most recognized survey instrument is the Maslach Burnout Inventory-Human Services Survey, a 22-item questionnaire based on the three core principles of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and personal accomplishment.

- Unfortunately, the amount and quality of evidence to prevent and treat burnout is low. A systematic review article found only 29 randomized controlled trials that looked at interventions in physicians and nurses to improve mental health, well-being, physical health, and lifestyle.

- Common interventions include sleep, exercise, social interaction, and mindfulness/prayer. Failure to address burnout can lead to anxiety, depression, mental illness, leaving medicine, and even suicide. It is important to identify risk factors and signs in ourselves and our colleagues.

Introduction

While there are multiple definitions of well-being, it commonly is described as a dynamic and ongoing process involving self-awareness and healthy choices, resulting in a successful and balanced lifestyle.1 Well-being incorporates a balance between the physical, emotional, intellectual, social, and spiritual realms, thus leading to a sense of accomplishment, satisfaction, and belonging. It protects us from the unique demands of medical training and life beyond the four walls of an emergency department (ED). Burnout results from chronic stress, which leads to emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and decreased feelings of personal accomplishment.2

Historically, burnout was seen as a sign of weakness within the requirements of our profession.4 Speaking about emotional exhaustion or self-care was a detriment in modern medical care. Burnout can be synonymous with impairment, with the labeling of burnout leading to further emotional isolation.5 Within the current medical schemata of team-based, patient-centered care, we know that emotional care for patients can yield a sustainable social return on investment.6 Why should emotional care for ourselves and each other be any different? The inherent conflict in balancing our personal and professional lives can lead to dissatisfaction in both. Our goal is to open a discussion about burnout, contributors that lead to burnout, and steps to deal with, minimize, and prevent burnout, which will facilitate better care for patients and caregivers alike.

What Is Burnout?

Burnout is a dysfunctional response to chronic, job-related stress. In 1974, Freudenberger initially coined the term.7 Later, in 1981, Maslach and Jackson developed the first burnout assessment tool, called the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI).2 Burnout is characterized by three core elements: emotional exhaustion, cynicism/depersonalization, and reduced professional efficacy/personal accomplishment.2 Emotional exhaustion is the most universally accepted and prevalent of the three cores and consists mainly of fatigue. Cynicism/depersonalization is affected by exhaustion, causing people to distance themselves emotionally from their work and the people they serve. Chronic and overwhelming demands increasingly become challenging to fulfill because of the first two core elements, ultimately leading to reduced professional efficacy/personal accomplishment.8 Although burnout does not appear in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-V), it recently was recognized as a syndrome in the 11th revision of the World Health Organization (WHO) International Classification of Disease (ICD-11) in 2019, with the definition as stated earlier.9

An Explosion of Interest and Focus on Burnout

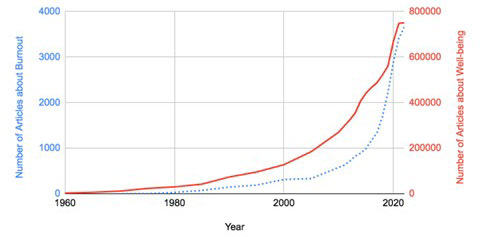

There has been increasing interest in the subject of burnout over the years. One can observe this by the increasing number of publications yearly on this topic. Figure 1 shows a rapid increase in the number of citations on burnout on PubMed from 1970 to 2022 (left Y-axis). Less known is a parallel explosion in the interest in well-being (right Y-axis).

Figure 1. Expanding Interest in Well-Being and Burnout from 1960 to 2022 |

|

This graph shows the number of PubMed articles for burnout and well-being per year from 1960 to 2022. The number of articles about burnout is plotted on the dotted line and the number of articles about well-being is plotted on the unbroken line. |

Scope of the Problem

Although initial research on burnout focused mainly on those working in the human services industry, its known effect since has expanded to those in various occupations across the globe.10,11 Anyone can be affected by burnout, but there is a higher prevalence of burnout in healthcare workers compared to the rest of the population.12 A Mayo Clinic study in 2015 compared 5,313 physicians with 5,392 employed nonphysicians. Physicians had higher levels of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and overall burnout compared to the general population using a two-item burnout measure. Even when adjusted for age, sex, relationship status, and hours worked per worker, physicians were at increased odds for burnout compared with the general population (odds ratio [OR], 1.97), as well as for lower rates of satisfaction with work-life balance (OR, 0.68).13 High levels of burnout also are seen in medical and surgical residents, with a prevalence of 51%. Rates vary depending on specialty, gender, age, and location.12

Every year, Medscape releases a report on burnout and depression in physicians. In 2022, Medscape released data from a survey of 13,069 physicians across 29 specialties from June to September 2021. It reported that approximately 47% of physicians felt burned out, a 5% absolute increase compared to the 2021 Medscape survey results, with the highest rates being seen in emergency medicine and critical care at 60% and 56%, respectively.14 Burnout extends to the nursing field as well. A 2021 report found that up to 95% of nurses have felt burned out in the past three years. Of these nurses, 47.9% were actively seeking less stressful nursing positions, looking to quit the profession entirely, or already had done so in the past three years.15

There is considerable overlap between burnout and the development of mental health disorders. In a recent worldwide survey of 5,931 cardiologists, 28% admitted to having a mental health condition.16 It also is important to note that this survey was conducted in 2019, before the COVID-19 pandemic.

Workplace Well-Being

Burnout has become such a ubiquitous condition that the Surgeon General of the United States recently published a report on its effect, prevention, and treatment, not only for the general workplace, but also for healthcare.17,18 The report focuses on and asserts the belief that “workplaces can be engines of mental health and well-being.” The report focuses on five essentials for workplace mental health and well-being: protection from harm, connection and community, work-life harmony, mattering at work, and opportunity for growth. The first essential, protection from harm, focuses on establishing a workplace that is physically and mentally safe and allows adequate rest and mental health support. Workplace violence in the ED is increasing. The American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) and the Emergency Nurses Association created a campaign called “No Silence on ED Violence” to draw attention to the problem. More details and resources can be found at https://stopedviolence.org/.

The second essential strives to create a culture built on trust, inclusion, collaboration, and belonging. The third essential focuses on creating a work-life harmony with increased workplace autonomy, more worker-oriented schedules, respect between work and home time, the ability to eat and drink while on shift, built-in breaks (particularly after difficult cases), and attention to the schedule to make emergency medicine a viable and enriching career. Some schedule modifications include the use of nocturnalists or weekend-only staff, limitation of night shifts after a certain age, and early completion of the schedule (particularly holiday schedules) that allow for family adjustments. The fourth essential builds on engaging workers in decisions, building a culture of gratitude, recognizing achievements, and connecting each worker with the company mission and their role in patient care. An example of this is providing feedback on all admitted cases, not just those with bad outcomes. The final essential focuses on the high level of training, education, mentoring, and ability for career advancement, and making sure feedback is facultatively healthy. There should be due process and transparency in business operations consistent with the policies of ACEP and the American Academy of Emergency Medicine.

These five essentials are building the framework where businesses and their most important asset, their people, can work together to facilitate trust, connection, community, and growth to construct a healthy national workforce.

Symptoms and Progression of Burnout

The symptoms of burnout can be categorized broadly into a five-stage model.19 The honeymoon phase (stage 1) includes positive symptoms of job satisfaction, optimism, and high productivity levels. The onset of stress (stage 2) can include cardiovascular symptoms, anxiety, reduced sleep quality, increased irritability, and neglect of personal needs. As stress becomes chronic (stage 3), the person may experience persistent fatigue, procrastination, social withdrawal, apathy, and cynicism. Burnout occurs in stage 4, causing self-doubt, social isolation, pessimism, escapist activities, and physical symptoms. Finally, habitual burnout (stage 5) ultimately leads to chronic sadness and mental and physical fatigue, and may even result in mental disorders, such as depression and anxiety.

Internal and External Factors that Contribute to Burnout

Internal and external risk factors can lead to burnout.20 Internal factors include those with idealistic expectations of themselves, high ambition, perfectionism, wanting to please others, and viewing work as the only meaningful activity. High demands at work, time constraints, lack of autonomy, long hours, multiple jobs, low wages, decreased morale, toxic work culture, and increasing responsibilities encompass some external factors for burnout. Various habits can lead to burnout, such as perfectionism, lack of self-advocacy, diminished levels of sleep (including night shift work), lack of exercise, failure to ask for support or help, and failure to engage in self-care activities.21 Just as various habits can contribute to burnout, burnout can form habits. Burnout often can produce habits of unhealthy lifestyle choices (alcohol, tobacco, and substance abuse), unhealthy diets, and poor work productivity and quality in one’s job.22,23

Diagnosis/Quantification of Burnout

There are numerous indexes for measuring burnout. Most of these adhere to some form of the three core elements of burnout outlined by Maslach and Jackson in the original MBI from 1981. Although numerous measurement indexes exist for burnout, the MBI is the most widely used worldwide. The original version of the MBI, now referred to as the Maslach Burnout Inventory-Human Services Survey (MBI-HSS), is a 22-item questionnaire based on the three core principles of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and personal accomplishment.

This survey initially was designed to assess burnout in occupations focused primarily on human services, such as physicians, nurses, counselors, teachers, etc. The MBI since has expanded to include people in any profession in the 16-item survey, the MBI-General Survey (MBI-GS). The survey focuses primarily on the three core principles of exhaustion, cynicism, and professional efficacy. There are three other forms that have more targeted populations: MBI-Educators Survey, MBI-Human Services Survey for Medical Personnel, and MBI-General Survey for Students.24,25

The Mayo Clinic has developed an easy-to-use, web-based Well-Being Index (WBI).26 The seven- to nine-question WBI focuses on six domains: meaning in work, quality of life, the likelihood of burnout, work-life integration, severe fatigue, and suicidal ideation.27 The WBI was designed to be completed in a few minutes via a mobile device and has been validated in multiple healthcare occupations, such as physicians, medical residents/fellows, pharmacists, nurses, medical students, and the general population. In addition, the WBI compares the individual to others in the same category across the nation, with results tracked over time. Resources to improve well-being are provided to those with abnormal scores.

There are numerous other burnout inventories. Some popular generalized inventories include the Oldenburg Burnout Inventory, the Copenhagen Burnout Inventory, the Burnout Assessment Tool, and the Shirom-Melamed Burnout Questionnaire.28-31 There also are occupation-specific burnout assessment tools, such as the Physician Burnout Questionnaire, School Burnout Inventory, the Athlete Burnout Questionnaire, and much more.32-34

Although there are multiple tools to measure burnout, there is a need for a generalized consensus on cutoffs to what constitutes burnout, making it difficult to obtain accurate measures of burnout prevalence on a large scale. For instance, a meta-analysis of 109,628 physicians from 182 studies across 45 countries found that the prevalence of burnout among physicians varied widely.35 Overall burnout ranged from 0% to 80.5%, while subcomponent analysis ranged from 0% to 86.2% for emotional exhaustion and 0% to 87.1% for a reduced sense of personal accomplishment. This considerable variation resulted from inconsistent measurements of what constitutes burnout among the articles chosen. There were 142 unique definitions for meeting overall burnout or burnout subscale criteria. Although most incorporated either the MBI-HSS or the MBI-GS, different cutoff values were applied to burned-out physicians between the studies, precluding any accurate conclusions on the prevalence of physician burnout.

The Costs of Burnout

Beyond the personal toll of burnout, there also is an economic price. A statistical model estimates that burnout costs from $2.6 billion to $6.3 billion per year, primarily because of the cost of physician turnover.36 Further, healthcare systems are becoming aware of the cost advantages of proactively limiting burnout.

An article laid out the business case for taking burnout seriously as part of a health system’s financial plan. This study used statistical modeling estimates to highlight the return on investment of preventing burnout at 12.5%.37 This is a conservative estimate, since costs primarily were focused on physician turnover and did not account for another feature of burnout, lost productivity. Preventive measures will be desperately needed; the Association of American Medical Colleges estimates there will be a shortage of 54,000 to 139,000 physicians by 2033.38

Effect of the COVID-19 Pandemic

On Jan. 30, 2020, the WHO declared a public health emergency of international concern because of the rising prevalence of COVID-19. At the time of the declaration, the death toll was officially 171. By the end of 2020, the death toll stood at 1,813,188, with some estimates of global death greater than 3 million.39

This large coronavirus wave shocked the world, severely affecting healthcare workers, especially those working in close contact with COVID-19 patients. Occupational stressors included higher workloads, the continual stress of possible personal suffering from prolonged sickness or death, inadequate sleep, excessive fatigue, and the continual need for sympathy with patients and families surrounding end-of-life periods. Added layers of personal protective equipment (PPE) contributed to dehydration, poor nutrition, and excessive fatigue.40 Numerous studies have shown higher levels of stress, anxiety, and depression in those in direct contact with COVID-19 patients vs. those without direct contact.41-43

One survey by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in 2022 found that nearly half of the 26,069 public health workers surveyed in the United States dealt with at least one indicator of anxiety, depression, or post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) during the COVID-19 pandemic, and one in 12 experienced suicidal thoughts.44 Less time dealing with job challenges and a continuously evolving field with changes in medical management and workplace regulations seems to have contributed to burnout, stress, anxiety, and depression.45

Another survey showed that 60.5% of nurses experienced emotional fatigue, 42.3% experienced depersonalization, and 60.6% experienced diminished self-adequacy.46 An extensive review comprising 14 meta-analyses, a systematic review, and an umbrella review of meta-analyses showed the extent of the COVID-19 pandemic’s profound effect on healthcare workers’ mental health. This extensive research showed the inevitability of being subjected to burnout from unprecedented stressful surroundings. Especially seen among nurses with the closest contact with patients, these circumstances led to PTSD, anxiety, depression, and a sincere feeling that it was not if, but when, they would come into contact with COVID-19, with the potential of long-term health effects and possible death.47

A survey of 2,440 physicians highlighted the increase in burnout from 38.2% to 62.8% throughout the pandemic.48 Mean depression scores increased by 6.1%, while work-life integration fell from 46.1% to 30.2%.

In an extensive healthcare survey of more than 20,000 respondents across 42 health systems, the researchers found COVID-19 adversely affected healthcare workers.49 Anxiety and depression were prevalent in 38%, work overload was present in 43%, and burnout was present in 29%. Interestingly, the feeling of being valued by their organization was the only factor found to be protective, ultimately resulting in a 40% reduction in burnout.49 This point will be discussed further later in this article.

The Ohio Physicians Health Program (OhioPHP) surveyed more than 13,000 healthcare providers and found significant changes in stress-related factors as the result of COVID-19.50 The survey uncovered a 347% increase in apathy; a 367% increase in feeling depleted at work; a 23% increase in alcohol use; an 87.5% increase in personal suicidal ideation; a 702% increase in depressed mood, depression, and hopelessness; and a 56% increase in workload.

Of note, one in four providers sought professional help for these feelings. Fifty-six percent did not seek help because of time constraints, 40% did not know where to seek help, and 31% did not seek help because of concerns about confidentiality.

Prevent Burnout or Promote Well-Being?

One of the significant changes needed within the medical community is a change to promote well-being instead of only preventing burnout. Two famous quotes describe this mentality. In the first Chinese medical textbook, Huang Dee Nai-Chang said, “The superior doctor prevents sickness. The mediocre doctor attends to impending sickness. The inferior doctor treats actual sickness.” Dr. “Patch” Adams famously said, “If you focus on the problem, you can’t see the solution. Never focus on the problem.”

A familiar axiom in medicine is “The most important question in medicine is ‘why’” — why did this happen to the patient? Only after answering this question can we develop a successful medical treatment plan. Falling short would be treating only the symptoms of the disease (i.e., putting a Band-Aid on it) and not addressing the root cause of the disease.

In a similar context, understanding our “why” as physicians can help us deal with factors leading to burnout and help prioritize habits that lead to personal well-being. The stronger our “why,” the more resilient we will be. Another way to answer the question of “why” is to figure out our purpose and find what gives our jobs real meaning.

“Ikigai” is a well-known concept in Japanese culture. Loosely translated, it means “purpose or meaning of life.” Although the concept of ikigai is common in Asia, it is not well-known in the Western world. A small study of Europeans and North Americans demonstrated that having a high sense of ikigai positively explained 31% of the variance in well-being scores and negatively explained 21% of the variance in depression scores.51

Lack of meaning is one of the factors that cause physicians so much frustration with electronic medical records (EMR). It is not just the added time EMR takes that contributes to burnout, but also the lack of meaning doctors feel when completing all the record-keeping.52 Most people feel in a flow state when operating near the top of their abilities or at the “top of their license.”53

Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi has published numerous studies focusing on this very subject. In his studies, one of the highest flow states was found in surgeons while they were performing surgery in the operating room. Working on completing EMR records is on the other end of the spectrum. Furthermore, putting effort into the EMR typically is viewed as needing to be more aligned with the values of improved patient care, since it reduces time with the patients and can interfere with interpersonal communication (although results are mixed).54 If charting is done after hours, it can erode personal and family time, thus further leading to burnout.

Finally, successive upgrades typically lead to small changes in workflow, which lowers efficiency. This has been recognized as a significant problem in clinical medicine. The American Medical Informatics Association, along with other health organizations, have put together a plan to try and reduce the documentation burden by 25% by the year 2025.55

To promote well-being, it is essential to understand the landscape involved. The Stanford Model of Professional Fulfillment is one of the most well-used models.56 This model has three main categories: a culture of well-being, efficiency of practice, and personal resilience. (See Table 1.) What can be seen immediately is that two-thirds of well-being mainly is in the employer’s control, and only one-third is a personal responsibility. It is true that physicians can and should have an effect on the efficiency of practice, but that can occur only in an environment that values their opinion and where they are treated as an essential part of the team, not just as employees.

Table 1. Factors in Professional Fulfillment 56 |

||

Culture of Wellness |

Efficiency of Practice |

Personal Resilience |

Leadership support |

Identification and redesign of inefficient work practices |

Self-care support |

Measurement of well-being |

Streamlining electronic medical records |

Safety nets for someone in crisis |

Values are aligned |

Realistic staff scheduling |

Peer-to-peer support |

Involvement of physicians in the redesign of workflow |

||

Building a constructive relationship between physicians and healthcare administration is critical to creating a cohesive environment. An excellent example of the effectiveness of this dyad of a physician-administrative partnership approach was seen in a randomized controlled trial of reducing burnout in 34 clinics and including 166 doctors.57 The comprehensive study showed a significant reduction in burnout from 21.8% to 7.1%. Furthermore, specific interventions to improve physician workflow led to a significantly higher 5.9 OR of less burnout. Lastly, working on targeted quality improvement projects also led to a significant 4.8 OR for less burnout. This study highlights the importance of administrative support and the work environment features contributing to physician burnout.

Well-Being

Personal resilience also is critical, since it is entirely under the physician’s control. The rest of this article will focus on methods to enhance well-being and, thus, reduce the risk of burnout.

Unfortunately, the amount and quality of evidence to prevent and treat burnout is low. A systematic review article found only 29 randomized controlled trials that looked at interventions in physicians and nurses to improve mental health, well-being, physical health, and lifestyle. These 29 studies totaled only 2,708 subjects.58 Another systematic review analyzed 19 studies totaling 1,550 physicians and did find some significant treatment effects, but the overall effect size was small.59 Furthermore, in both review articles, most studies that showed a treatment effect were time-consuming (hours per week for multiple weeks), which may have worked in a study environment, but have questionable long-term sustainability.

A small randomized controlled trial done at the Mayo Clinic had sustainable results out to one year, but it also required one hour of physician time every other week. Interestingly, that time was protected and paid for by the institution.60 This continues to highlight the need for the administration to support well-being efforts. Empowerment and engagement at work increased by 5.3 points in the intervention arm vs. a 0.5-point decline in controls. Rates of depersonalization decreased by 15.5% in the intervention arm vs. a 0.8% increase in the control arm. No statistically significant differences in stress, symptoms of depression, overall quality of life, or job satisfaction were seen. What was the intervention in this study? A simple, facilitated physicians small-group meeting.

A systematic review of 74 resilience studies showed that only nine met the quality requirements to be included. Of these, only four were randomized controlled trials.61 The reviewers found that the degree of effect and overall quality could have been higher in each study, making it hard to recommend any of the studied interventions.

Although the research interest and data on burnout are large, reproducible, and robust, the research on preventing or treating burnout or enhancing well-being is much more sparse. What can we do? One area with much more data that we could use as a surrogate for burnout or well-being is stress. The stress literature is much more robust and well-developed than the current state of burnout studies. Furthermore, stress is the underlying problem in almost all incidences of burnout. Mitigating stress already is considered an essential part of well-being.62

This brings about another important point. Prevention should focus on maintaining well-being rather than treating burnout. After burnout occurs, it is much more challenging and costlier to treat. Furthermore, as demonstrated in the Medscape and OhioPHP surveys, more than 40% of the doctors answered that they would not seek professional help for several reasons.50

Our efforts should focus on reducing stressful reactions that accumulate over time and lead to burnout. Acute treatments are needed for physicians in crisis, such as those abusing alcohol and drugs or contemplating quitting or, worse yet, suicide. Most of our efforts should be on preventing this at the earliest stage possible rather than expending monumental effort at the very end. Now is an excellent opportunity to shift our culture toward one promoting well-being rather than fighting the end stages of burnout. Recognizing that stress is a key component to burnout has changed the focus to preventing stress to prevent burnout.63

What Is Stress? How Does it Harm Us?

Stress has long been considered harmful to a person’s health, but the exact mechanism was not well-defined. A well-performed mechanistic study correlated perceived stress with amygdalar activation, bone marrow activation, and arterial inflammation. In addition, it drew a connection to how all these correlated to cardiovascular events.64 The authors found that increased perceived stress positively correlated with increased mid-brain amygdalar activation, bone marrow activation, vascular inflammation, C-reactive protein (CRP) levels, and cardiovascular events. Of note, quantitative positron emission tomography imaging was used to assess and quantify brain, bone marrow, and vascular activity. Table 2 shows strategies for increasing well-being and decreasing the risk of burnout.

Table 2. Personal Strategies for Increasing Well-Being and Decreasing Burnout |

|

Factor |

Target Goal |

Ikigai |

Find your why; maybe find it again51 |

Work hours |

30 to 45 hours per week65-68 |

Sleep |

Six to nine hours per night73-76 |

Attitude adjustment |

Positive attitude, practice gratitude69-70 |

Exercise |

45 minutes per day, three to five times per week77-80 |

Time outdoors |

As much as possible81-89 |

Social activity |

Engage daily, and with a large circle of contacts85,86 |

Meditation or prayer |

Daily87-92 |

Workplace Management

As briefly discussed earlier, the workplace either can increase stress or decrease it. Emergency medicine, by its very nature, is a stressful career. In fact, the very features that draw people to the field contribute to the stress. Long hours, night and weekend coverage, an unpredictable workflow, and the loud, chaotic environment all contribute to stress. Making the environment work for the staff while preserving the excitement that is emergency care is tricky. But there are some options.

The work environment needs to be conducive to care. This means limiting boarders (inpatient overflow). Because boarding has become routine, few in hospital administration even see this as a problem. Just because there is inpatient overflow does not mean they have to be in the ED. At least one institution successfully converted an old patient ward in the basement to a boarding unit. Load leveling is another approach.

Excess patient load should be distributed among all units. In one institution, the ED accepted and cared for the first eight boarders, then every inpatient unit took one patient. Where patients cannot be moved from the physical ED, staff can be reassigned to level the load.

Working in the ED is difficult, but there are ways to reduce that stress. All staff should be able to eat and drink while on duty. If leaving the ED is not an option, then eating in the ED can be permitted. It is a myth that The Joint Commission or another agency forbids this. There should be a room where staff can go to debrief and decompress after an emotional case. There also should be a lactation room (not a bathroom) for those who breast feed.

Workload is a critical factor for well-being. A review of randomized controlled trials of residency hours demonstrated that shorter work hours led to significantly less emotional exhaustion and dissatisfaction, and improved overall well-being.65 Interestingly, personal sleep time, patient length of stay, and serious medical errors were not different.

In one study examining 50,273 nurses across the United States, factors such as more than 40 hours per week worked, a stressful working environment, and inadequate staffing were reported as statistically significant, leading to burnout in nursing.66 In the general population, the risk of burnout is higher with lower levels of education and socioeconomic status in women, while burnout is highly linked to marital status in men, with higher rates of burnout seen in single, divorced, or widowed men.67

These are but a few of the components of a well workplace, one that reduces the natural stress of the ED. A good medical director speaks of wellness frequently and listens to their staff’s suggestions for making their workplace a better one. A retrospective study of more than 1,900 individuals followed for at least 10 years found that an average workweek of more than 45 hours was associated with a 16% increase in cardiovascular events.68 There was a dose-response curve in that the risk increased to 35% after 55 hours per week and doubled when the work hours exceeded 75 hours per week. There also was increased risk after the workweek hours became less than 30, thus creating a U-shaped curve. Unfortunately, the authors did not speculate on the potential reason for this. A potential reason for this U-shaped curve might be that when people work a lower number of hours, it could be associated with increased financial stress or underemployment, which also can lead to stress.

An Attitude of Gratitude

The mind is a very powerful thing, allowing people to work far past the point of exhaustion. There are several powerful examples of the effect of attitude on health.

Studies of attitude often are seen as pseudoscience. However, several good examples demonstrate the power of the mind backed up by the scientific method and, more importantly, quantitative and objective data.

In a randomized controlled trial of gratitude journaling, researchers asked participants to write down five things they were grateful for at the end of each day for 14 days. The authors were able to show significant increases in positive affect, subjective happiness, and life satisfaction and a decrease in negative affect and depression.69

In another study of heart failure patients, the authors measured emotional response to gratitude and directly measured inflammatory biomarkers.70 These included C-reactive protein, tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), interleukin-6 (IL-6), interferon-gamma-gamma (IFN-gamma), and suppression of tumorigenicity 2 (ST2). Gratitude was associated with more sleep, less depressed mood, less fatigue, and, importantly, significantly and quantifiably lower inflammatory biomarkers.

Another component of attitude is emotion. Anger and laughter, interestingly, have opposite effects on our physiology. A meta-analysis of nine studies of angry outbursts found that the OR for myocardial infarction or acute coronary syndrome increased to 4.74, the OR for ischemic stroke increased to 3.62, and the OR for intracranial aneurysm rupture increased to 6.3. Finally, the OR for ventricular arrhythmias increased from 1.8 to 3.2 after an angry outburst. The risk period extends for two hours after the episode.`

Another study showed that mental stress, even from watching a movie, could affect physiologic function. In a small mechanistic study of brachial artery flow reactivity, volunteers were scanned before and after watching 15 to 30 minutes of either a comedy (“There’s Something About Mary” or “Kingpin”) or an intense war movie (“Saving Private Ryan”).72 After watching the comedy, brachial artery flow reactivity increased by 22%. After watching the war movie, brachial artery flow reactivity decreased by 35%, with effects lasting up to 48 hours.

If anger and stress can lead to a higher risk of serious cardiovascular events and laughter can improve cardiovascular function, we can see how attitude could have a profound effect on our well-being, not just from an emotional standpoint but from a physiologic one as well. Another vital point to remember is that the effects of laughter were protective for up to two days, compared to the two hours of increased risk with anger. Further studies looking into the association of laughter with hard clinical outcomes are needed before prescribing it as a therapeutic intervention.

You Can Sleep When You Are Dead …

Rest and recovery, especially sleep, are just as important as workload. In a large sample of 444,306 Americans, researchers found that about 34% do not get the recommended seven hours of sleep per night.73 Sleep is critical for optimal health and cognitive function. The American Academy of Sleep Medicine and the Sleep Research Society reviewed 5,314 scientific articles on sleep and published a consensus statement. They concluded that averaging less than seven hours of sleep per night is associated with weight gain, obesity, diabetes, hypertension, heart disease, stroke, depression, and increased risk of mortality. Furthermore, diminished sleep is associated with impaired immune function, increased errors, and a greater risk of accidents.74

Poor sleep can exacerbate the effect of cardiac risk factors leading to death from heart disease, stroke, and cancer.75 This study is fascinating, since sleep duration was measured in a sleep lab instead of self-reported. In this study of 1,654 subjects, less than six hours of sleep was associated with an increased mortality risk. The limitation of this study was that there was only a single determination of sleep duration, but the strength is its objective measure, not self-reported sleep.

Similar to workload, sleep also follows a U-shaped curve. In a large observational study of 461,347 patients taken from the UK Biobank, short sleep duration (less than seven hours) was associated with a 19% increased risk of myocardial infarction (MI).76 Sleeping longer than nine hours was associated with a 34% increased risk of MI. Interestingly, one extra hour of sleep mitigated the risk of MI by 20%.

Personal Wellness: Exercise and Stress

The most studied method to mitigate stress likely is exercise.77 In the Aerobics Center Longitudinal Study, 4,888 subjects were followed for approximately 15 years.78 Low levels of negative emotions led to a 34% reduction in mortality. High levels of cardiorespiratory fitness also led to a significant 46% reduction in mortality. The best group, those with low levels of negative emotions and high cardiorespiratory fitness, had a 63% reduction in mortality. This study looked at the relative effect of both factors but did not directly test the hypothesis of exercise mitigating the effects of stress.

That hypothesis was tested in a study of 549 patients stratified by stress level and put on an exercise program.79 High stress levels in this study led to a four-fold increase in mortality (22% vs. 5%, high stress vs. low stress). Mortality decreased by 60% in the group that improved its exercise level. More impressive was the finding that people in the high-stress/high-exercise group did not experience any mortality during the study period. However, the high-stress/low-exercise group had a 19% fatality rate. Interestingly, in the low-stress group, exercise did not significantly affect survival. A limiting factor in this study was the mean follow-up of 3.5 years.

Exercise and Mental Health

In an extensive study of more than 1.2 million Americans, exercise was strongly correlated to improved mental health.80 All forms of exercise were associated with this positive effect, with effect size varying from 11.8% to 22.3%, depending on the activity. Exercise also was associated with a 43.2% reduction in days with poor mental health. Finally, the ideal duration and frequency for maximal mental health were around 45 minutes daily, three to five times per week.

Go Outside, Get into Nature, Go Forest Bathing

A large study of more than 900,000 Danes looked at the relationship between exposure to green spaces during childhood and mental illness during adolescence and adulthood.81 They found that those with the lowest green space exposure had an associated 55% increase in overall mental health conditions. An interesting point of this study is that the researchers only looked at access to green space, not if subjects used them.

One aspect of green spaces is forest bathing. Forest bathing is an intentional walk in nature for its potential therapeutic benefits. Although there has been much interest, the field has been hampered by early studies that were small in size, with varying interventions (walking for 15 minutes vs. six hours) and potential biases (especially publication bias). In a meta-analysis of 17 studies of forest bathing, there was a small but nonsignificant reduction in systolic blood pressure, but a uniform decrease in depression scores.82 Although this was a well-done meta-analysis, each study used in the analysis was very small and numbered only from six to 60 patients. A more recent and more extensive review and meta-analysis examined 11 studies ranging in size from 126 to 2,257 patients studied for the potential benefits of forest bathing.83 The review showed that forest bathing was associated with decreased blood pressure, reduced negative emotions, and decreased biomarkers of inflammation.

Although there has been quantitative data on forest bathing (blood pressure, biomarker measurement, standardized and scored survey instruments), many still desire more objective measures. One well-described objective measure of stress is cortisol levels. A recent meta-analysis looked at eight studies with 348 participants. It showed that forest bathing results in at least a short-term lowering of cortisol levels.84

Be Social

Social interaction has a substantial effect on well-being. In an extensive survey done by Cigna, more than 20,000 people described the state of loneliness in America.85 Forty-six percent of respondents felt lonely, 47% felt left out, 43% felt that their relationships were not meaningful, and only 53% felt that they had any meaningful in-person interactions. Of those with daily meaningful in-person interaction, 88% said their overall mental and physical health was at least good. In addition, 89% of those who said their relationships with their coworkers were at least good also reported at least good overall health. Of note, Generation Z (those born around 1997 to 2012) was the loneliest generation and the least likely to say they were in good, very good, or excellent health. Interestingly, social media use did not predict loneliness.

The Health Professionals Follow-up Study is an excellent example of the power of social connection. This study tracked 34,901 male health professionals for more than 24 years. One of the analyses examined the interaction between social connection and suicide over that period.86 Those with the highest social integration score had a 64% lower relative risk of suicide than the least integrated group. Furthermore, several variables strongly affected suicide risk. Marriage was associated with a 40% reduction in suicide risk. Having a large social network of family and friends was associated with a 50% reduction. Attending religious services at least once a week was associated with a 51% risk reduction.

Mindfulness and Prayer

Two similar strategies that researchers have studied are mindfulness (a type of meditation) and prayer. Both mindfulness and prayer are forms of quiet time and a source of self-reflection. Mindfulness meditation has been shown to have a moderate effect on well-being.87 The limitations of using this technique typically are related to time, the need for a guide (which often necessitates a physical meeting), and sustainability. A possible solution to these issues is using prerecorded sessions on mobile devices.

A small study of 238 workers showed that mindfulness sessions on mobile devices significantly affected well-being, distress, job strain, and perceptions of workplace social support.88 These effects were accomplished with 10 to 20 minutes of mindfulness sessions daily. Furthermore, there was a small but significant reduction in self-reported blood pressure over the course of the study in the intervention group, with the effects lasting up to 16 weeks.

For those who practice religion, a form of mindfulness practice is prayer. An interesting statistical modeling study of more than 2,600 Americans examined the interplay of stress, worship attendance, and personal prayer.89 The researchers found that worship attendance could mitigate stress response, but personal prayer was required for worship to have a significant benefit.

Worship attendance and prayer both were modeled using normal distributions. The response to stress by worship attendance was similar at low, mean, and high levels of attendance. However, the amount of personal prayer (1 standard deviation [SD] below, mean, and 1 SD above) significantly affected the response to stress at each worship level.

In another study, researchers looked at the effect of prayer on nurses.90 This study looked at 335 nurses at a single medical center who participated in Salat or prayer. Prayer was associated with decreased job stress and increased well-being. In contrast to the modeling study noted previously, group (or congregational) prayer had a more significant effect than individual prayer.

There are multiple subtypes of prayer. A recent review article compared four types: prayer efficacy (the belief that prayer can solve problems), devotional prayer (praise of God and prayer for others), prayers for personal support, and prayer expectancies (whether God can answer prayers).91 Prayers of prayer efficacy, prayers for personal support, and one form of devotional prayer (asking God for forgiveness) all were associated with worse anxiety. Only devotional prayer (praise of God) and prayer expectancies correlated with lower anxiety.

Teaching, like medicine, is a high-stress career field. In a small randomized controlled trial of 50 teachers and staff, prayer significantly improved job satisfaction and reduced emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and psychological impairment.92 This study, like meditation studies, did require prayer teaching sessions.

This study was done at a Catholic institution and, along with the earlier cited Muslim nurse study, represented work environments that favor prayer. It is unknown if prayer would have the same effects in a more secular work culture.

A final quantitative study looked at gene expression in the context of well-being. This study examined transcriptome analysis before and after hedonic or eudaimonic exercises.93 “Hedonic” represents an individual’s positive emotional experience, while “eudaimonic” represents experiences based on meaning and a noble purpose outside of oneself. The researchers studied 80 individuals and 53 genes before and after to measure changes in the transcriptome. Hedonic well-being was associated with increased pro-inflammatory gene expression and decreased antibody gene expression. Eudaimonic well-being was associated with no change in pro-

inflammatory expression but increased antibody gene transcription. We look forward to further research in this area and a possible connection between pursuing meaning and a noble purpose with improved immune function.

Conclusion

Developing and maintaining wellness is essential to the continued success of the medical field. Within the rigors of the medical profession, we often forget to take care of ourselves while dealing with the complexities of patient care. It is hoped that increasing discussions about wellness will help curtail burnout in the medical profession. Medicine is a complex and stressful job, but it does not have to lead to burnout. Healthcare is one of the few careers encompassing all four components of ikigai: passion, skill, helping others, and reasonable compensation.

A quote that sums up medicine well is from the character Jimmy Dugan in the movie “A League of Their Own.” He said, “Of course it’s hard. It’s supposed to be hard. If it were easy, everyone would do it. Hard is what makes it great!” Medicine is hard, but that is why it is so great.

REFERENCES

- Eckleberry-Hunt J, van Dyke A, Lick D, Tucciarone J. Changing the conversation from burnout to wellness. Survey of Anesthesiology 2015;59:15-16.

- Maslach C, Jackson SE. The measurement of experienced burnout. Journal of Organizational Behavior 1981;2:99-113.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. NHE Fact Sheet. https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/NHE-Fact-Sheet#:~:text=NHE%20grew%202.7%25%20to%20%244.3%20trillion%20in%202021%2C

- Maslach C, Goldberg J. Prevention of burnout: New perspectives. Applied and Preventive Psychology 1998;7:63-74.

- Iacovides A, Fountoulakis KN, Kaprinis S, Kaprinis G. The relationship between job stress, burnout and clinical depression. J Affect Disord 2003;75:209-221.

- Leck C, Upton D, Evans N. Social return on investment: Valuing health outcomes or promoting economic values? J Health Psychol 2016;21:1481-1490.

- Freudenberger HJ. Staff burn-out. Journal of Social Issues 1974;30:159-165.

- Maslach C, Schaufeli WB, Leiter MP. Job burnout. Annu Rev Psychol 2001;52:397-422.

- ICD-11 for Mortality and Morbidity Statistics. QD85 Burnout. https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en#/http://id.who.int/icd/entity/129180281

- Schutte N, Toppinen S, Kalimo R, Schaufeli W. The factorial validity of the Maslach Burnout Inventory-General Survey (MBI-GS) across occupational groups and nations. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology 2000;73:53-66.

- Bocheliuk VY, Zavatska NY, Bokhonkova YO, et al. Emotional burnout: Prevalence rate and symptoms in different socio-professional groups. Journal of Intellectual Disability-Diagnosis and Treatment 2020;8:33-40.

- Low ZX, Yeo KA, Sharma VK, et al. Prevalence of burnout in medical and surgical residents: A meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019;16:1479.

- Shanafelt TD, Hasan O, Dyrbye LN, et al. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance in physicians and the general US working population between 2011 and 2014. Mayo Clin Proc 2015;90:1600-1613.

- Kane L. Physician Burnout & Depression Report 2022: Stress, Anxiety, and Anger. Medscape. Published 2022. https://www.medscape.com/2022-lifestyle-burnout

- Curry M. Nursing CE Central: Nurse Burnout Study 2021. Nursing CE Central. Published Aug. 6, 2021. https://nursingcecentral.com/nurse-burnout-study-2021/#:~:text=Nursing%20burnout%20is%20a%20major,within%20the%20last%20three%20years

- Sharma G, Rao SJ, Douglas PS, et al. Prevalence and professional impact of mental health conditions among cardiologists. J Am Coll Cardiol 2023;81:574-586.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The U.S. Surgeon General’s Framework for Workplace Mental Health and Well-Being. Published 2022. https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/workplace-mental-health-well-being.pdf

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Addressing Health Worker Burnout – The U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory on Building a Thriving Health Workforce. Published 2022. https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/health-worker-wellbeing-advisory.pdf

- De Hert S. Burnout in healthcare workers: Prevalence, impact and preventative strategies. Local Reg Anesth 2020;13:171-183.

- Kaschka WP, Korczak D, Broich K. Burnout: A fashionable diagnosis. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2011;108:781-787.

- Gustavo M. 8 toxic habits that lead to burnout. Psych2Go. Published Oct. 8, 2021. https://psych2go.net/7-toxic-habits-that-lead-to-burnout/

- Chandler KD. Work-family conflict is a public health concern. Pub Health Pract (Oxf) 2021;2:100158.

- Mental Health America. Mind the Workplace: Employer Responsibility to Employee Mental Health. Published 2022. https://www.mhanational.org/mind-workplace

- Schaufeli WB, Bakker AB, Hoogduin K, et al. On the clinical validity of the Maslach Burnout Inventory and the Burnout Measure. Psychol Health 2001;16:565-582.

- Mind Garden. Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI). https://www.mindgarden.com/117-maslach-burnout-inventory-mbi

- Well-Being Index. https://www.mywellbeingindex.org/

- Dyrbye LN, Satele D, Shanafelt T. Ability of a 9-item well-being index to identify distress and stratify quality of life in US workers. J Occup Environ Med 2016;58:810-817.

- Demerouti E, Bakker AB. The Oldenburg Burnout Inventory: A good alternative to measure burnout and engagement. In: Halbesleben JRB, ed. Handbook of Stress and Burnout in Health Care. Nova Science Publishing, Inc.;2008:65-78.

- Kristensen TS, Borritz M, Villadsen E, Christensen KB. The Copenhagen Burnout Inventory: A new tool for the assessment of burnout. Work & Stress 2005;19:192-207.

- Schaufeli WB, Desart S, De Witte H. Burnout Assessment Tool (BAT)—Development, validity, and reliability. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020;17:9495.

- Lundgren-Nilsson Å, Jonsdottir IH, Pallant J, Ahlborg G Jr. Internal construct validity of the Shirom-Melamed Burnout Questionnaire (SMBQ). BMC Public Health 2012;12:1.

- Moreno-Jimenez B, Barbaranelli C, Galvez Herrer M, Garrosa Hernandez E. The Physician Burnout Questionnaire: A new definition and measure. TPM 2012;19:325-344.

- Salmela-Aro K, Kiuru N, Leskinen E, Nurmi JE. School Burnout Inventory (SBI) reliability and validity. European Journal of Psychological Assessment 2009;25:48-57.

- Raedeke TD, Smith AL. Athlete Burnout Questionnaire (ABQ). Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology 2009.

- Rotenstein LS, Torre M, Ramos MA, et al. Prevalence of burnout among physicians: A systematic review. JAMA 2018;320:1131-1150.

- Han S, Shanafelt TD, Sinsky CA, et al. Estimating the attributable cost of physician burnout in the United States. Ann Intern Med 2019;170:784-790.

- Shanafelt T, Goh J, Sinsky C. The business case for investing in physician well-being. JAMA Intern Med 2017;177:1826-1832.

- Association of American Medical Colleges. The Complexities of Physician Supply and Demand: Projections from 2018 to 2033. Published June 2020. https://www.aamc.org/media/45976/download?attachment

- World Health Organization. The true death toll of COVID-19: Estimating global excess mortality. https://www.who.int/data/stories/the-true-death-toll-of-covid-19-estimating-global-excess-mortality

- Sharifi M, Asadi-Pooya AA, Mousavi-Roknabadi RS. Burnout among healthcare providers of COVID-19; a systematic review of epidemiology and recommendations. Arch Acad Emerg Med 2020;9:e7.

- Wu Y, Wang J, Luo C, et al. A comparison of burnout frequency among oncology physicians and nurses working on the frontline and usual wards during the COVID-19 epidemic in Wuhan, China. J Pain Symptom Manage 2020;60:e60-e65.

- Chen Q, Liang M, Li Y, et al. Mental health care for medical staff in China during the COVID-19 outbreak. Lancet Psychiatry 2020;7:e15-e16.

- Lai J, Ma S, Wang Y. Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Netw Open 2020;3:e203976.

- Koné A, Horter L, Thomas I, et al. Symptoms of mental health conditions and suicidal ideation among state, tribal, local, and territorial public health workers—United States, March 14-25, 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2022;71:925-930.

- De Simone S, Vargas M, Servillo G. Organizational strategies to reduce physician burnout: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Aging Clin Exp Res 2021;33:883-894.

- Hu D, Kong Y, Li W, et al. Frontline nurse’ burnout, anxiety, depression, and fear statuses and their associated factors during the COVID-19 outbreak in Wuhan, China: A large-scale cross-sectional study. EClinicalMedicine 2020;24:100424.

- Chirico F, Ferrari G, Nucera G, et al. Prevalence of anxiety, depression, burnout syndrome, and mental health disorders among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A rapid umbrella review of systematic reviews. J Health Soc Sci 2021;6:209-220.

- Shanafelt TD, West P, Dyrbye LN, et al. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life integration in physicians during the first 2 years of the COVID-19 pandemic. Mayo Clin Proc 2022;97:2248-2258.

- Prasad K, McLoughlin C, Stillman M, et al. Prevalence and correlates of stress and burnout among U.S. healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A national cross-sectional survey study. EClinicalMedicine 2021;35:100879.

- Ohio Physicians Health Program. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Health and Well-being of Ohio’s Healthcare Workers: Executive Summary. Published 2022. https://simplebooklet.com/covid-19survey#page=1

- Wilkes J, Garip G, Kotera Y, Fido D. Can ikigai predict anxiety, depression, and well-being? Int J Ment Health Addict 2022; Mar 1:1-13. doi: 10.1007/s11469-022-00764-7. [Online ahead of print].

- Nelson K, Stewart G. Primary care transformation and physician burnout. J Gen Intern Med 2019;34:7-8.

- Csikszentmihalyi M. Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. Harper and Row; 1990.

- Alcocer Alkureishi M, Lee WW, Lyons M, et al. Impact of electronic medical record use on the patient-doctor relationship and communication: A systematic review. J Gen Intern Med 2016;31:548-560.

- American Medical Informatics Association. AMIA 25x5: Reducing documentation burden to 25% of current state in five years. https://amia.org/about-amia/amia-25x5

- Stanford Medicine. The Stanford Model of Professional Fulfillment. https://wellmd.stanford.edu/about/model-external.html

- Linzer M, Poplau S, Grossman E, et al. A cluster randomized trial of interventions to improve work conditions and clinician burnout in primary care: Results from the Healthy Work Place (HWP) Study. J Gen Intern Med 2015;30:1105-1111.

- Mazurek Melnyk B, Kelly SA, Stephens J, et al. Interventions to improve mental health, well-being, physical health, and lifestyle behaviors in physicians and nurses: A systematic review. Am J Health Promot 2020;34:929-941.

- Panagioti M, Panagopoulou E, Bower P, et al. Controlled interventions to reduce burnout in physicians: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med 2017;177:195-205.

- West CP, Dyrbye LN, Rabatin JT, et al. Intervention to promote physician well-being, job satisfaction, and professionalism: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med 2014;174:527-533.

- Lavin Venegas C, Nkangu MN, Duffy MC, et al. Interventions to improve resilience in physicians who have completed training: A systematic review. PLoS One 2019;14:e0210512.

- Lee FJ, Stewart M, Brown JB. Stress, burnout, and strategies for reducing them: What’s the situation among Canadian family physicians? Can Fam Physician 2008;54:234-235.

- Bruce SP. Recognizing stress and avoiding burnout. Currents in Pharmacy Teaching and Learning 2009;1:57-64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cptl.2009.05.008

- Tawakol A, Ishai A, Takx RA, et al. Relation between resting amygdalar activity and cardiovascular events: A longitudinal and cohort study. Lancet 2017;389:834-845.

- Sephien A, Reljic T, Jordan J, et al. Resident duty hours and resident and patient outcomes: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Med Educ 2022;57:221-232.

- Shah MK, Gandrakota N, Cimiotti JP, et al. Prevalence of and factors associated with nurse burnout in the US. JAMA Netw Open 2021;4:e2036469.

- Ahola K, Honkonen T, Isometsä E, et al. Burnout in the general population. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2006;41:11-17.

- Conway SH, Pompeii LA, Roberts RE, et al. Dose-response relation between work hours and cardiovascular disease risk: Findings from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics. J Occup Environ Med 2016;58:221-226.

- Fofonka Cunha L, Campos Pellanda L, Tozzi Reppold C. Positive psychology and gratitude interventions: A randomized clinical trial. Front Psychol 2019;10:584.

- Mills PJ, Redwine L, Wilson K, et al. The role of gratitude in spiritual well-being in asymptomatic heart failure patients. Spiritual Clin Pract (Wash D C) 2015;2:5-17.

- Mostofsky E, Penner EA, Mittleman MA. Outbursts of anger as a trigger of acute cardiovascular events: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Heart J 2014;35:1404-1410.

- Miller M, Mangano C, Park Y, et al. Impact of cinematic viewing on endothelial function. Heart 2006;92:261-262.

- Liu Y, Wheaton AG, Chapman DP, et al. Prevalence of healthy sleep duration among adults—United States, 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2016;65:137-141.

- Consensus Conference Panel; Watson NF, Badr MS, Belenky G, et al. Recommended amount of sleep for a healthy adult: A joint consensus statement of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine and Sleep Research Society. J Clin Sleep Med 2015;11:591-592.

- Fernandez-Mendoza J, He F, Vgontzas AN, et al. Interplay of objective sleep duration and cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases on cause-specific mortality. J Am Heart Assoc 2019;8:e013043.

- Daghlas I, Dashti HS, Lane J, et al. Sleep duration and myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2019;74:1304-1314.

- O’Keefe EL, O’Keefe JH, Lavie CJ. Exercise counteracts the cardiotoxicity of psychosocial stress. Mayo Clin Proc 2019;94:1852-1864.

- Ortega FB, Lee DC, Sui X, et al. Psychological well-being, cardiorespiratory fitness, and long-term survival. Am J Prev Med 2010;39:440-448.

- Milani RV, Lavie CJ. Reducing psychosocial stress: A novel mechanism of improving survival from exercise training. Am J Med 2009;122:931-938.

- Chekroud SR, Gueorguieva R, Zheutlin AB, et al. Association between physical exercise and mental health in 1.2 million individuals in the USA between 2011 and 2015: A cross-sectional study. Lancet Psychiatry 2018;5:739-746.

- Engemann K, Pedersen CB, Arge L, et al. Residential green space in childhood is associated with lower risk of psychiatric disorders from adolescence into adulthood. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2019;116:5188-5193.

- Yi Y, Seo E, An J. Does forest therapy have physio-psychological benefits? A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022;19:10512.

- Stier-Jarmer M, Throner V, Kirschneck M, et al. The psychological and physical effects of forests on human health: A systematic review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021;18:1770.

- Antonelli M, Barbieri G, Donelli D. Effects of forest bathing (shinrin-yoku) on levels of cortisol as a stress biomarker: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Biometeorol 2019;63:1117-1134.

- Cigna Healthcare. Cigna 2018 U.S. Loneliness Index. https://www.cigna.com/assets/docs/newsroom/loneliness-survey-2018-fact-sheet.pdf

- Tsai AC, Lucas M, Sania A, et al. Social integration and suicide mortality among men: 24-year cohort study of U.S. health professionals. Ann Intern Med 2014;161:85-95.

- Spinelli C, Wisener M, Khoury B. Mindfulness training for healthcare professionals and trainees: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Psychosom Res 2019;120:29-38.

- Bostock S, Crosswell AD, Prather AA, Steptoe A. Mindfulness on-the-go: Effects of a mindfulness meditation app on work stress and well-being. J Occup Health Psychol 2019;24:127-138.

- Rainville G. The interrelation of prayer and worship service attendance in moderating the negative impact of life event stressors on mental well-being. J Relig Health 2018;57:2153-2166.

- Achour M, Muhamad A, Syihab AH, et al. Prayer moderating job stress among Muslim nursing staff at the University of Malaya Medical Centre (UMMC). J Relig Health 2021;60:202-220.

- Upenieks L. Unpacking the relationship between prayer and anxiety: A consideration of prayer types and expectations in the United States. J Relig Health 2022;30:1-22.

- Chirico F, Sharma M, Zaffina S, Magnavita N. Spirituality and prayer on teacher stress and burnout in an Italian cohort: A pilot, before-after controlled study. Front Psychol 2020;10:2933.

- Fredrickson BL, Grewen KM, Coffey KA, et al. A functional genomic perspective on human well-being. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2013;110:13684-13689.