Author

Daniel Migliaccio, MD, FPD, FAAEM, Clinical Associate Professor, Division Director of Emergency Ultrasound, Ultrasound Fellowship Director, Department of Emergency Medicine, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Peer Reviewer

Katherine Baranowski, MD, FAAP, FACEP, Chief, Division of Pediatric Emergency Medicine, Department of Emergency Medicine, New Jersey Medical School, Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, Newark

Executive Summary

- Teen patients are at an increased risk of medical adverse outcomes, including preeclampsia, preterm birth, intrauterine fetal growth retardation, and infant death.

- Indications for emergency contraception include any female patient in whom pregnancy is not desired and who experienced any of the following: unprotected vaginal sexual intercourse, sexual assault, or vaginal sexual intercourse with concern for contraceptive failure.

- Generally, the law protects minors in allowing them access to sexual health testing and contraception without parental consent, but laws can be variable, so clinicians should be aware of local protocols.

- Clinicians also should have an increased concern for sexual abuse or sex trafficking in pregnant adolescents. One study showed that two-thirds of pregnant adolescents had been sexually abused. Another demonstrated that women who had a history of childhood sexual abuse were twice as likely to become pregnant during adolescence.

- The differential for first-trimester vaginal bleeding is broad but includes benign nonobstetric causes (vaginitis, cervicitis, trauma), bleeding in a viable intrauterine pregnancy (threatened abortion), spontaneous abortion (miscarriage), and ectopic pregnancy.

- It is important to note that tachycardia may not be seen in a ruptured ectopic pregnancy if there is diaphragmatic/vagal nerve stimulation from intraperitoneal blood products.

- The discriminatory level of beta-human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) is the hormone level at which an intrauterine pregnancy should be seen on transvaginal ultrasound. This level varies with the type of ultrasound machine and skill set of the ultrasonographer; however, it typically is considered to be ~1,500 mIU/mL. Even if the beta-hCG level is < 1,500 mIU/mL, the pelvic ultrasound still is indicated to evaluate for signs of ectopic pregnancy (adnexal mass, free fluid in the cul-de-sac). This is crucial because ectopic pregnancies can have beta-hCG values well below the discriminatory level.

This article is the first of a two-part series that focuses on an important emergency medicine topic — teenage pregnancy. In this first part, the author focuses on the unique features that affect diagnosis and management of pregnancy in adolescence. Part two will focus on obstetrical emergencies in pregnant teenagers.

— Ann M. Dietrich, MD, FAAP, FACEP, Editor

Introduction and Epidemiology

In the United States, there are approximately 17.4 births per 1,000 adolescent females aged 15-19 years and 0.2 births per 1,000 aged 10-14 years. 1-3 There has been a steady decrease in these numbers over the last decade, which is attributed in part to widespread availability and education on contraceptives.4 Disparities in adolescent pregnancy are seen among various racial groups, with birth rates being twice as high in Hispanic and non-Hispanic Black teens when compared to non-Hispanic whites and 2.5 times as high in American Indian/Alaskan Native teens.1

Meanwhile, common risk factors that are associated with adolescent pregnancy include concomitant mental health conditions, lower socioeconomic conditions, and geographic locations with fewer publicly funded family medical providers. Protective factors against adolescent pregnancy include higher levels of education and using contraceptives.2,5,6 Overall outcomes of pregnancies in adolescents (< 20 years of age) in the United States include 25% that are terminated electively, 15% that result in miscarriage, and 61% that result in a birth.7 It is estimated that 82% of pregnancies in mothers aged 15-19 years are unintentional.8

This article is part one of a two-part narrative discussing the unique features of teenage pregnancy. This article will discuss the social impacts of teenage pregnancy as well as outline key factors in the diagnosis and management of early adolescent pregnancies, including topics such as first trimester abdominal pain and vaginal bleeding. Part two will focus on obstetrical emergencies in pregnant adolescents.

Clinical Awareness, Social Effects, and Importance of Prevention

Teen pregnancy and subsequent childbearing have a significant impact on social and economic factors for both teen parents and their children. Therefore, pregnancy recognition/diagnosis and prevention carry a critical role. Pediatric healthcare providers, including those in the emergency department (ED), should have a low threshold for suspecting pregnancy in adolescents.

Despite this, the diagnosis of teen pregnancy frequently is missed. One study compared the presenting complaints and historical information of pregnant adolescents (≤ 16 years of age) whose diagnosis of pregnancy was made or not made in the ED of a tertiary-care hospital. The researchers found that < 10% of patients who had pregnancy diagnosed mentioned the possibility of pregnancy at initial triage, and 10.5% denied having had sexual activity. Sixty-eight percent of patients whose pregnancy diagnosis was missed had no documentation of their menstrual or sexual history in the chart.9 Teen patients are at increased risk of medical adverse outcomes, including preeclampsia, preterm birth, intrauterine fetal growth retardation, and infant death.10-18 Therefore, prompt diagnosis and establishment of prenatal care are critical.

In addition to medical adverse outcomes, there are numerous detrimental social and economic effects of teen pregnancy. Adolescent mothers are less likely to receive a high school diploma or to enroll in college. They also are more likely to live in poverty and face unemployment than women who delay childbearing. Adolescent fathers also are less likely to complete a college education and have been found to earn less income and have higher levels of unemployment. Children of teen mothers are more likely to have health and cognitive disorders and are more likely to drop out of high school. Female children of teenage mothers are more likely to have an adolescent pregnancy themselves, while male children of teenage mothers have higher rates of incarceration.14,19-23

Given the potential downstream socioeconomic and mental health outcomes, education and prevention of adolescent pregnancy are of substantial importance. Emergency medicine clinicians also should be familiar with emergency contraception, both its options and indications. Emergency contraception is a method of preventing pregnancy after intercourse has occurred. Indications for emergency contraception include any female patient in whom pregnancy is not desired who experienced any of the following: unprotected vaginal sexual intercourse, sexual assault, or vaginal sexual intercourse with concern for contraceptive failure. Generally, the law protects minors in allowing them access to sexual health testing and contraception without parental consent, but laws can be variable, so clinicians should be aware of local protocols. See Table 1 for information regarding emergency contraception options, their timing of use relative to unprotected intercourse, efficacy, and availability.24,25

Table 1. Emergency Contraception24-28 |

|||

| Contraception | Timing | Efficacy | Availability |

Levonorgestrel (Plan B) |

Up to three days after unprotected intercourse |

1.7% to 2.6% pregnancy risk |

Available over the counter |

Ulipristal acetate (Ella) |

Up to five days after unprotected intercourse |

1.2% to 1.8% pregnancy risk |

Requires prescription |

Copper intrauterine device |

Up to five days after unprotected intercourse, but may be effective at any time in the menstrual cycle when a urine pregnancy test is negative |

0.1% pregnancy risk |

Requires outpatient office visit and clinician insertion (typically not available in an emergency department setting) |

Combined oral contraceptives (Dose: 100 mcg to 120 mcg ethinyl estradiol + 0.5 mcg to 0.6 mg levonorgestrel per dose x 2 doses 12 hours apart) |

Up to five days after unprotected intercourse |

11% pregnancy risk |

Requires prescription |

Pregnancy Diagnosis, Initial Steps, and Access to Care

A 16-year-old female presents to the ED with several days of constipation. She has had associated bloating and nausea, but no vomiting. She has otherwise been well. She denies any vaginal bleeding or discharge. She is sexually active with one male partner, and she has not been using any contraception. Her last menstrual period was five weeks ago.

There are some unique features to keep in mind when diagnosing pregnancy in adolescents. Adolescent patients may be less forthcoming regarding their suspicion of possible pregnancy, and, therefore, pediatric healthcare providers should routinely collect a menstrual and sexual history on female patients.9 Providers also should consider pregnancy in patients presenting with symptoms of early pregnancy, including amenorrhea, nausea, breast pain, fatigue, weight gain or bloating, and urinary frequency.29

A pregnancy diagnosis typically is confirmed with either urine or serum beta-human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) testing. While most serum pregnancy tests can detect hCG levels as low as 1 mIU/mL to 2 mIU/mL, urine pregnancy tests are typically less sensitive, with detection levels beginning at 20 mIU/mL to 50 mIU/mL.29 Diagnosis, or support thereof, also can be confirmed with a pelvic ultrasound, which is discussed in more detail later.

When ordering a pregnancy test, it is important to provide both pre-test and post-test counseling to patients. Pre-test counseling includes notifying the patient that the test will be ordered and also asking the teen how she would feel or what she would do should the test result be positive. Parental consent and notification laws vary by state, but nearly every state allows testing for pregnancy without parental consent. Most states also allow women younger than 18 years of age to consent to prenatal care without a parent.30 The first step of post-test counseling is to inform the adolescent of a positive test and elicit their thoughts and feelings about the test result. Adolescents have a wide range of emotions in relation to a positive result, and appropriate resources should be provided, particularly if there is any concern for self-harm.

Pregnancy and thoughts of child rearing are a time of immense emotional and physical change, and for those without adequate support or coping skills, maladaptive coping techniques (substance abuse, overt denial, etc.) can occur. The incidence of pregnancy denial at 20 weeks' gestation is estimated to be one in 475, and the incidence of denial persisting until delivery is one in 2,500.31

Denial of pregnancy has been associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes, including lack of prenatal care, precipitous and often unassisted delivery, and fetal abuse or neglect.32 It is important for emergency clinicians to be aware of pregnancy denial. If it is suspected, coordination of care with either inpatient consultation or close outpatient follow-up with both an obstetrician and a psychological/psychiatric team may be indicated.

Sexual Abuse and Adolescent Pregnancy

Clinicians also should have an increased concern for sexual abuse or sex trafficking. One study showed that two-thirds of adolescent women who became pregnant had been sexually abused.33 Another demonstrated that women who had a history of childhood sexual abuse were twice as likely to become pregnant during adolescence.34 Childhood sexual abuse also has been closely associated with post-traumatic stress disorder, substance use disorders, and it can contribute to other areas of impaired judgment, such as an increase in high-risk sexual behaviors. Asking an adolescent about a history of abuse may allow for early trauma intervention and ultimate improvement in psychosocial and clinical outcomes. Several hospitals are adopting trauma specialists (typically a specifically trained social worker) who may be available to provide support and resources to the patient.

Support, Options, and Follow-up Care

Despite variation of laws by state requiring notification of parents, it typically is recommended that the patient be encouraged to inform her parent(s) or an adult support person as well as the father of the baby. All available options should be discussed with the patient. This includes three predominant options: motherhood, abortion, and adoption.35 These options should be, at a minimum, briefly mentioned and discussed.

Clinicians in the ED often do not have the time or resources to have an extensive conversation regarding options, and therefore a timely referral to another individual who can provide unbiased counseling is important. In this current political climate, very close care and attention must be taken regarding abortion counseling and the options presented. Providers must be up to date with state and local laws. Adolescents < 15 years of age have been shown to be less likely to obtain prenatal care.36 Helping to facilitate coordination of prenatal care and providing early pregnancy resources is advised. Whenever possible, the ED clinician should be the one to physically call and schedule a patient appointment and, at minimum, should provide contact information with a referral.

Substance Use in Teen Pregnancy

Rates of unplanned pregnancies are higher in teens who use substances, including tobacco, alcohol, marijuana, and opioids.37 All of these substances can be teratogenic to a developing fetus.

Combined with delayed pregnancy recognition and prolonged fetal exposure to these substances, unintended teen pregnancies pose a higher health risk to both the mother and developing fetus.

It is important, therefore, for providers to take a thorough medication and substance use history in all pregnant adolescents presenting to the ED. Clinicians also should discuss the adverse effects of drugs, alcohol, and smoking on both the fetus and the patient. Additionally, patients should be started on prenatal vitamins. If the patient is on any known teratogenic medications (and the pregnancy is desired or a decision regarding continuation of the pregnancy has not yet been made), instructions for safely discontinuing these medications should be given. Table 2 shows some of the most common prescription teratogens, although the list is not all-inclusive. A medication reconciliation and pharmacy consult may be beneficial in a time-constrained ED when available to review all of the patient’s medications and determine any need for adjustment.

Table 2. Teratogenic Prescription Medications38 |

|

| Medication Type | Medications |

Neurologic medications (antiepileptics/migraine/psychiatric medications) |

|

Antimicrobial medications |

|

Anticoagulant medications |

|

Antithyroid medications |

|

Immunocompromising drugs/chemotherapy |

|

Hormonal medications |

|

Acne medications |

|

Perinatal and Postpartum Depression

A 16-year-old female, gravidity 1, parity 0, at 28 weeks’ gestation presents to the ED with a loss of hope and depressive symptoms. The patient describes suicidal ideation with thoughts of intentional overdose to end her life. She denies any ingestion or self-harm. She has no prior psychiatric history or inpatient psychiatric admissions. She lives at home with one parent, and the father of the baby is no longer involved.

Perinatal and postpartum depression can affect any mother or pregnant woman, independent of race, age, education, or income. However, postpartum depression has been shown to be twice as common in adolescent mothers when compared to adults.39 Additionally, adolescents aged 15-19 years who have been diagnosed with a major mental illness have been shown to be nearly three times as likely to have an adolescent pregnancy when compared to those without mental illness.40 In addition to an increased incidence of perinatal and postpartum depression in teens, recognition and access to care often are limited or hindered secondary to a shortage in pediatric psychiatric care, as well as the stigma surrounding teen pregnancy.41 Although less frequent than in the outpatient setting, ED clinicians do encounter pregnant adolescents throughout the perinatal and postpartum period and can serve a key role in identification and potential diagnosis of perinatal mental health issues. ED clinicians should use a validated screening tool for evaluation if there is clinical or patient concern for perinatal depression, such as the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (viewable online at https://stan.md/304uAyE).42 However, basic screening questions, including assessing a patient’s mood, suicidal ideation, as well as home safety, should be performed during every ED visit from a pregnant adolescent. Early identification can lead to facilitated follow-up for proper intervention by behavioral health specialists.

Intimate Partner Violence During Pregnancy

Approximately 3.2% of women report physical abuse in the form of being pushed, hit, slapped, kicked, choked, or physically hurt by an intimate partner during their most recent pregnancy, and the prevalence of intimate partner violence (IPV) is even higher in teen mothers at nearly 7%.25 IPV has been associated with both adverse maternal and fetal outcomes, including preterm delivery, low birth weight, maternal traumatic injury, and perinatal maternal mental health disorders, such as depression, suicidality, and post-traumatic stress.6 Therefore, routine screening for IPV is necessary to help identify, and thus reduce, violence and improve outcomes. In the ED, clinicians routinely should ask teen mothers about IPV.

First-Trimester Vaginal Bleeding

A 17-year-old female, gravidity 1, parity 0, at 10 weeks’ gestation presents to the ED with lower abdominal cramping and vaginal bleeding for the past four hours. She has not yet had an ultrasound during this pregnancy. She is otherwise healthy and has had no prior abdominal surgeries. Vital signs are within normal limits.

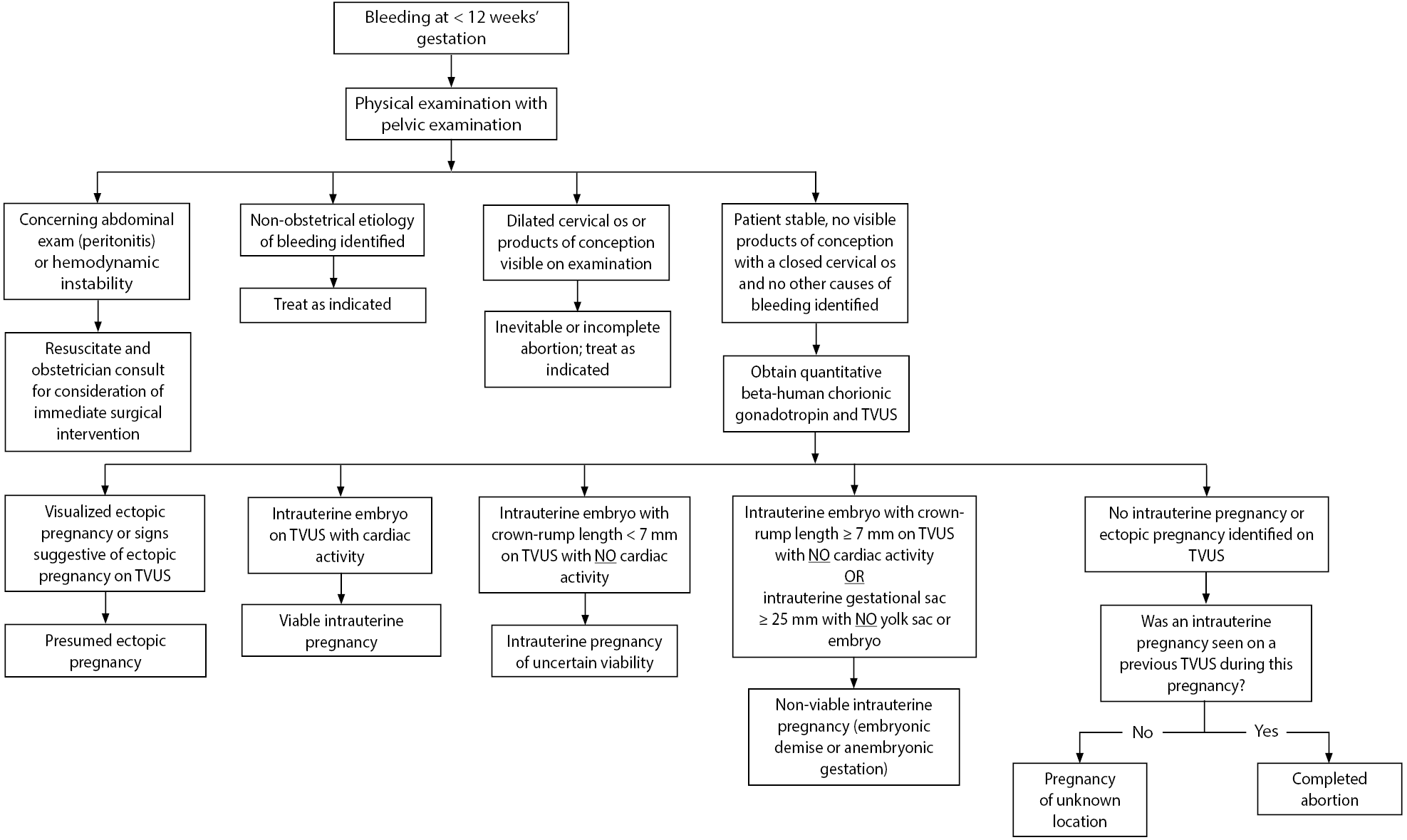

About one-fourth of women will experience some degree of first-trimester vaginal bleeding during pregnancy, and adolescent pregnancies are no exception.43,44 The differential for first-trimester vaginal bleeding is broad but includes benign nonobstetric causes (vaginitis, cervicitis, trauma), bleeding in a viable intrauterine pregnancy (threatened abortion), spontaneous abortion (miscarriage), and ectopic pregnancy.45 When it comes to early pregnancy diagnoses, many terms are used. (See Table 3.) Figure 1 displays a diagnostic algorithm for first-trimester vaginal bleeding.

Table 3. Early Pregnancy Diagnoses and Terminology |

|

| Diagnosis | Symptom |

Threatened abortion |

Vaginal bleeding < 20 weeks' gestation in which there is an ultrasound-confirmed, viable, intrauterine pregnancy with a closed cervix |

Viable intrauterine pregnancy |

Intrauterine embryo with cardiac activity and a closed cervix |

Intrauterine pregnancy of uncertain viability |

Intrauterine embryo of crown-rump length < 7 mm, with closed cervix, and no cardiac activity |

Spontaneous abortion |

Spontaneous loss of pregnancy < 20 weeks' gestation

|

Embryonic demise/missed abortion |

Embryo with a crown-rump length ≥ 7 mm without cardiac activity |

Pregnancy of unknown location |

Positive pregnancy test without an intrauterine or ectopic pregnancy identified on transvaginal ultrasound |

Anembryonic gestation |

Gestational sac ≥ 25 mm without a yolk sac or embryo |

Ectopic pregnancy |

A pregnancy that is outside of the uterus |

Subchorionic hemorrhage |

Blood present between the chorion and the uterine wall |

Figure 1. Diagnostic Algorithm for First-Trimester Vaginal Bleeding |

|

TVUS: Transvaginal ultrasound Adapted from Reproductive Health Access Project. First trimester bleeding algorithm. Updated Nov. 1, 2017. https://www.reproductiveaccess.org/resource/first-trimester-bleeding-algorithm/ and Hendriks E, MacNaughton H, Mackenzie MC. First trimester vaginal bleeding: Evaluation and management. Am Fam Physician 2019;99:166-174. |

The first step in evaluating a patient presenting with vaginal bleeding is obtaining a thorough history and examination. It is important to obtain information regarding the patient’s menstrual history and whether she has had an ultrasound during this pregnancy. This helps facilitate gestational dating and, importantly, whether the pregnancy is known to be intrauterine. Obtain an obstetrical history with the number of prior pregnancies and births (gravidity and parity — Gs and Ps) and history of complications/outcomes of prior pregnancies. Ask questions to help quantify the amount of bleeding (pads per hour being saturated, the passage of blood clots, and comparison to the patient’s normal menstrual period).

Determine the degree and location of pain, if there is any, and whether there are any other associated symptoms concerning for hypovolemia or anemia (e.g., dizziness, syncope, shortness of breath, chest pain). Then, assess vital signs and perform an examination. The physical exam should pay close attention to vital sign derangements that may indicate severe blood loss and/or a ruptured ectopic pregnancy, such as tachycardia or hypotension.

However, it is important to note that tachycardia may not be seen in a ruptured ectopic pregnancy if there is diaphragmatic/vagal nerve stimulation from intraperitoneal blood products. Signs of hemodynamic instability or peritoneal signs on abdominal examination may indicate the need for prompt evaluation by an obstetrician for emergent surgical intervention. The physical exam should include a speculum exam to evaluate for nonobstetrical causes of bleeding, quantify the degree of bleeding (spotting vs. hemorrhage), and assess for visible products of conception or clots in the cervical os to suggest the diagnosis of incomplete abortion. If there are products of conception present in the os, it is important to remove this tissue because it can help to slow bleeding, and the tissue can be sent to pathology.

Additional laboratory assessment typically is indicated and includes a quantitative beta-hCG level, hemoglobin analysis, a pelvic ultrasound, urinalysis, and a type and screen (to determine the patient’s Rhesus [Rh] status). Additional studies may include a complete blood count if there is concern for larger volumes of blood loss and a gonorrhea/chlamydia and wet prep/potassium hydroxide (if indicated per history or examination). Patients with first-trimester bleeding also warrant a pelvic ultrasound.

A quantitative beta-hCG level will help to indicate whether an intrauterine pregnancy (IUP) and/or fetal cardiac activity should be visible on ultrasound. The discriminatory level of beta-hCG is the hormone level at which an IUP should be seen on transvaginal ultrasound.46 This level varies with the type of ultrasound machine and skill set of the ultrasonographer; however, it typically is considered to be ~1,500 mIU/mL.47,48 Even if the beta-hCG level is < 1,500 mIU/mL, the pelvic ultrasound still is indicated to evaluate for signs of ectopic pregnancy (adnexal mass, free fluid in the cul-de-sac). This is crucial because ectopic pregnancies can have beta-hCG values well below the discriminatory level.

A positive pregnancy test with an empty uterus and the presence of free fluid in the right upper quadrant (RUQ) on ultrasonography is highly concerning for ectopic pregnancy and warrants an emergent obstetrical consultation. An ED/point-of-care ultrasound of the RUQ in a patient where there is concern for ectopic pregnancy can greatly reduce the time to diagnosis and, therefore, prompt treatment.49

Pregnancy of Unknown Location

A pregnancy of unknown location describes when a patient who has a positive pregnancy test, is hemodynamically stable, and has a benign abdominal exam, but there is no evidence of IUP or ectopic pregnancy on ultrasonography. For these patients, the monitoring of symptoms and ectopic return precautions (i.e., worsened pain, increased bleeding, dizziness, syncope) should be discussed in conjunction with an obstetrical (OB) consultation. Additionally, serial quantitative beta-hCG testing and repeat ultrasounds are indicated until a definitive diagnosis can be made.

Intrauterine Pregnancy of Unknown Viability

An intrauterine pregnancy of unknown viability describes the scenario when a patient has vaginal bleeding, a confirmed IUP on ultrasound, but no detection of fetal cardiac activity. The patient’s beta-hCG level and the size of the embryo can help indicate whether this is likely to be a missed abortion vs. an early IUP that will go on to be a viable pregnancy. A beta-hCG level of > 5,000 mIU/mL to 6,500 mIU/mL and a crown-rump length of ≥ 7 mm are more suggestive of a missed abortion.50 Unless there is definitive evidence of a missed abortion as suggestive earlier, repeat ultrasound should be performed in seven to 10 days to confirm viability.45

Threatened Abortion

A threatened abortion describes the scenario when a patient has vaginal bleeding but a confirmed viable IUP on ultrasound. Once fetal cardiac activity has been confirmed on ultrasonography, the risk of spontaneous abortion decreases significantly to approximately 11%, but detection of a subchorionic hemorrhage can increase this risk despite the presence of cardiac activity.51,52 Management of threatened abortion includes discussions with patients regarding bleeding precautions (more than two pads per hour for more than two hours or development of dizziness, chest pain, shortness of breath, or syncope), routine outpatient obstetrician follow-up, and repeat ultrasound if bleeding continues.

Types of Spontaneous Abortion: Incomplete, Inevitable, Missed, and Anembryonic Gestation

Spontaneous abortion describes the scenario when a patient has an IUP on ultrasound but no fetal cardiac activity despite either a previous ultrasound showing cardiac activity or an embryo with crown-rump length ≥ 7 mm. In these cases, there are typically three options for management (expectant, medical, and surgical), and physicians should counsel patients and use shared decision-making in conjunction with an OB consultant to guide management choice. Patient mental health and complication risk are similar among all three treatments.53,54

- Expectant management is watchful waiting and letting the pregnancy pass without any further interventions. This typically is effective for incomplete abortion; however, it is less effective for missed abortions.55

- Medical management includes administering medications (typically 800 mcg intravaginal misoprostol ± 200 mg oral mifepristone). Although it has not been shown to increase completion rates for incomplete abortions, it is more effective than expectant management for missed abortions.56,57

- Surgical management typically is performed by uterine vacuum aspiration, which is an office-based procedure that usually allows for less uncertainty in terms of completion and fewer days of bleeding.

Importantly, there have been several new laws instated regarding abortion care and the provision of medical and/or surgical management. Providers need to be familiar with these regulations and follow state, local, and institutional policy. All patients should be offered contraception with outpatient follow-up after early pregnancy loss.

Ectopic Pregnancy

Ectopic pregnancy describes the scenario when a patient has an adnexal mass or extrauterine embryo confirmed by ultrasound or free fluid in the cul-de-sac (along with the absence of an IUP when otherwise normally expected) in the presence of a positive pregnancy test. Keep in mind that an IUP on ultrasonography requires the presence of both an intrauterine gestational sac and yolk sac. Without the presence of a yolk sac or fetal pole, the fluid-filled structure could be a pseudo-gestational sac that can be seen with ectopic pregnancy. The incidence of ectopic pregnancy in the United States is 1% to 2%, and 6% of maternal deaths are due to ruptured ectopic pregnancies.58 Risk factors for ectopic pregnancy include previous ectopic pregnancy, tubal surgery, intrauterine device use, in vitro fertilization in current pregnancy, previous sexually transmitted infections or pelvic inflammatory disease, and tobacco use/smoking.59-65 Similar to spontaneous abortion, there are three management options for ectopic pregnancy (expectant, medical, and surgical) in conjunction with an OB consultant. The criteria for each are:

- Expectant: beta-hCG level < 1,000 mIU/mL, ectopic mass < 3 cm with no fetal cardiac activity, minimal pain or bleeding, no evidence of rupture, patient reliable for follow-up care.66

- Extensive counseling and surveillance with repeat beta-hCG levels every 48 hours to confirm decreasing levels and then every week until negative.67

- Medical: beta-hCG level < 2,000 mIU/mL, ectopic mass ≤ 3.5 cm with no fetal cardiac activity, minimal symptoms with stable vital signs, no evidence of rupture, patient reliable for follow-up care.

- Intramuscular methotrexate followed by trending of beta-hCG levels.47

- Surgical: advanced ectopic (high-beta-hCG, large mass, fetal cardiac activity), contraindications to methotrexate, signs of rupture or severe symptoms, unreliability for follow-up care.

- Salpingectomy or salpingostomy.

Finally, an Rh status should be determined with vaginal bleeding during early pregnancy. Although the risk of alloimmunization is low (1.5% to 2%), patients with an Rh-negative status should receive Rho(D) immune globulin (Rhogam) within 72 hours of pregnancy loss at a dose of 120 mcg to 300 mcg.68

Hyperemesis Gravidarum

A 15-year-old female, gravidity 1, parity 0, at 10 weeks’ gestation presents to the ED with three weeks of persistent nausea and vomiting, and she has been unable to tolerate oral intake for the past two days. She reports more than 10 episodes of non-bloody, non-bilious emesis today. She denies any diarrhea, constipation, fever, diarrhea, vaginal bleeding or discharge.

Approximately 75% of pregnant women will have some degree of nausea with or without vomiting during early pregnancy.69,70 The onset of nausea typically is between four and six weeks’ gestation, with a peak around weeks nine through 12. For the majority of women, these symptoms resolve by mid-pregnancy. For most, these symptoms are not severe enough to affect daily life. However, 0.3% to 2% of pregnant women develop hyperemesis gravidarum, a condition that is characterized by severe vomiting that results in weight loss of > 5%, ketonuria, electrolyte abnormalities, and dehydration that are refractory to standard outpatient medical treatment.69 These patients often will require admission for intravenous fluid hydration. Risk factors for hyperemesis gravidarum include both fetal and maternal factors, as described in Table 4.71,72 Maternal complications of hyperemesis gravidarum include Wernicke’s encephalopathy, central pontine myelinolysis, acute tubular necrosis, Mallory-Weiss tears, pneumomediastinum, splenic avulsion, and social/psychological impacts (anxiety, depression, lost work time).73-75

Table 4. Risk Factors for Hyperemesis Gravidarum |

|

| Fetal-Related Risk Factors | Maternal-Related Risk Factors |

|

|

On presentation, patients with hyperemesis gravidarum present with severe vomiting and associated symptoms, such as weight loss, orthostasis, and presyncope. Common exam findings often include signs of dehydration, including tachycardia, positive orthostatic vital signs, dry mucous membranes, and poor skin turgor. It is important to remember that hyperemesis gravidarum is a diagnosis of exclusion and, therefore, a broad differential should be considered. Other causes of vomiting in pregnancy may include gastroenteritis; gastroparesis; biliary colic or cholecystitis; pancreatitis; appendicitis; pyelonephritis; ovarian torsion; diabetic ketoacidosis; migraine headaches; preeclampsia, hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelet count; acute fatty liver of pregnancy; and molar pregnancy.76-78 Molar pregnancies are rare abnormal pregnancies that result from aberrant fertilization. They are more common among maternal extremes of age, including ≤ 15 years. Molar pregnancies typically result in higher serum beta-hCG levels and are associated with a higher prevalence of hyperemesis gravidarum.79 These pregnancies carry a risk of becoming locally invasive in the uterus and can metastasize, causing malignant disease.80

Diagnostic workup often includes urinalysis, complete metabolic panel, and serum quantitative beta-hCG and thyroid stimulating hormone. Imaging typically is not indicated unless there is clinical concern for a molar pregnancy or an alternative etiology of vomiting that would require imaging for diagnosis. Laboratory abnormalities commonly seen with hyperemesis gravidarum include a hypokalemic, hypochloremic metabolic alkalosis, ketonuria, transaminitis with liver function tests typically two to three times the upper normal limit, and hemoconcentration.77

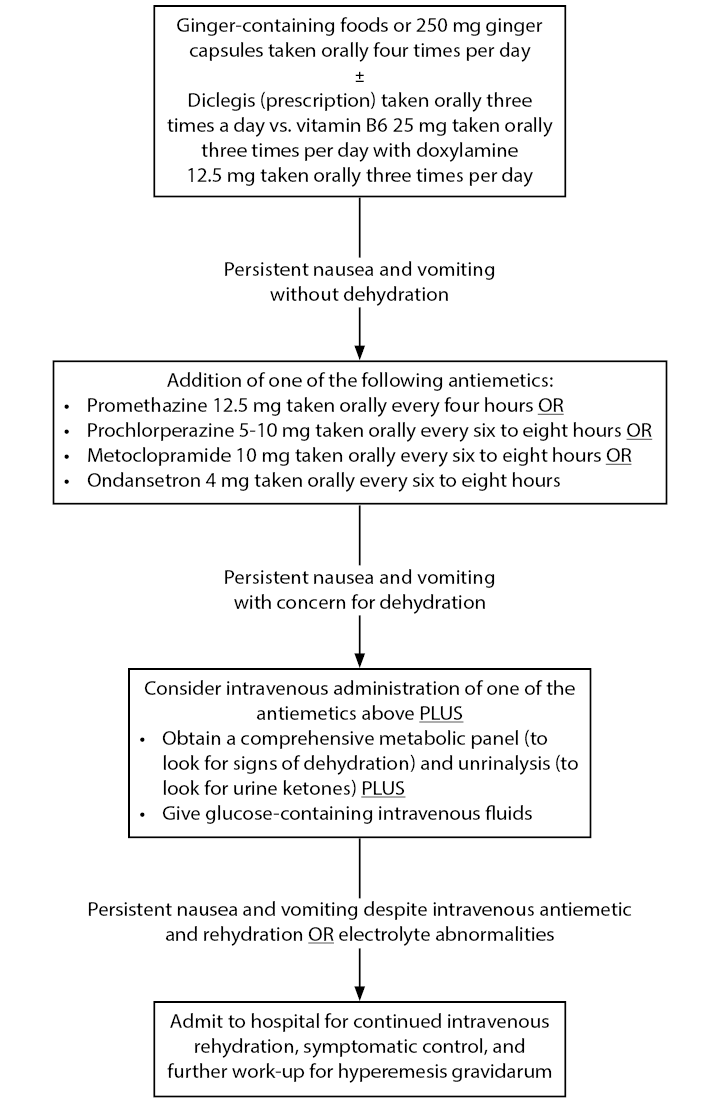

Treating vomiting in pregnancy is multimodal, including dietary modifications, over-the-counter medications, prescribed medications, and parenteral fluids and nutrition for refractory cases. Figure 2 discusses management options and indications for these therapeutic interventions.70,77 Patients with evidence of laboratory abnormalities and/or who are unable to tolerate oral intake despite administration of antiemetics and glucose-containing fluids may warrant obstetrics consultation for admission. It is important to note that diclegis is the only category A prescription available and that using other antiemetics warrants a risk-benefit discussion with the patient.

Figure 2. Therapeutic Interventions for Nausea and Vomiting in Pregnancy |

|

Conclusion

Emergency medicine clinicians understand pregnancy-related complications and management. An additional focus of pregnancy in the adolescent population should be an impetus on counseling and prevention, given the significant social and economic adverse impacts of teen pregnancy. Several high-risk conditions are at least equally, if not more, prevalent in adolescent mothers than in adult mothers, including pregnancy denial, substance use disorders, sexual assault and intimate partner violence, and peripartum and postpartum depression. It is important that ED clinicians be aware of these conditions and ensure that deliberate screening, counseling, and arrangement of appropriate follow-up is performed routinely from the ED.

Two of the most common pregnancy-related presentations to the ED include first-trimester vaginal bleeding and nausea and vomiting. ED clinicians should be well-informed on the clinical presentation, risk factors, diagnostic workup, and management of these conditions.

References

- Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Osterman MJK, Driscoll AK. Births: Final data for 2018. Nat Vital Stat Rep 2019;68:1-47.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Reproductive health: Teen pregnancy. Updated Nov. 15, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/teenpregnancy/about/index.htm

- United Nations Statistics Division. Demographic Yearbook 2013. Published 2015. http://unstats.un.org/unsd/demographic/products/dyb/dyb2013/Table10.pdf

- Lindberg LD, Santelli JS, Desai S. Changing patterns of contraceptive use and the decline in rates of pregnancy and birth among U.S. adolescents, 2007-2014. J Adolesc Health 2018;63:253-256.

- Maslowsky J, Powers D, Hendrick CE, Al-Hamoodah L. County-level clustering and characteristics of repeat versus first teen births in the United States, 2015-2017. J Adolesc Health 2019;65:674-680.

- Maravilla JC, Betts KS, Couto E, et al. Factors influencing repeated teenage pregnancy: A review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2017;217:527-545.

- Kost K, Maddow-Zimet I, Arpaia A. Pregnancies, births and abortions among adolescents and young women in the United States, 2013: National and state trends by age, race and ethnicity. Published September 2017. https://www.guttmacher.org/report/us-adolescent-pregnancy-trends-2013

- Finer LB, Zolna MR. Unintended pregnancy in the United States: Incidence and disparities, 2006. Contraception 2011;84:478-485.

- Causey AL, Seago K, Wahl NG, Voelker CL. Pregnant adolescents in the ED: Diagnosed and not diagnosed. Am J Emerg Med 1997;15:125-129.

- Fraser AM, Brockert JE, Ward RH. Association of young maternal age with adverse reproductive outcomes. N Engl J Med 1995;332:1113-1117.

- Olausson PM, Cnattingius S, Goldenberg RL. Determinants of poor pregnancy outcomes among teenagers in Sweden. Obstet Gynecol 1997;89:451-457.

- Rees JM, Lederman SA, Kiely JL. Birth weight associated with lowest neonatal mortality: Infants of adolescent and adult mothers. Pediatrics 1996;98:1161-1166.

- Phipps MG, Blume JD, DeMonner SM. Young maternal age associated with increased risk of postneonatal death. Obstet Gynecol 2002;100:481-486.

- Paranjothy S, Broughton H, Adappa R, Fone D. Teenage pregnancy: Who suffers? Arch Dis Child 2009;94:239-245.

- Malabarey OT, Balayla J, Klam SL, et al. Pregnancies in young adolescent mothers: A population-based study on 37 million births. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2012;25:98.

- Ganchimeg T, Ota E, Morisaki N, et al. Pregnancy and childbirth outcomes among adolescent mothers: A World Health Organization multicountry study. BJOG 2014;121(suppl 1):40-48.

- Traisrisilp K, Jaiprom J, Luewan S, Tongsong T. Pregnancy outcomes among mothers aged 15 years or less. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 2015;41:1726-1731.

- Brosens I, Muter J, Gargett CE, et al. The impact of uterine immaturity on obstetrical syndromes during adolescence. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2017;217:546-555.

- Perper K, Peterson K, Manlove J. Diploma attainment among teen mothers. Child Trends. Washington;2010.

- Hoffman SD, ed. Kids Having Kids: Economic Costs and Social Consequences of Teen Pregnancy. The Urban Institute Press;2008.

- Assini-Meytin LC, Green KM. Long-term consequences of adolescent parenthood among African-American urban youth: A propensity score matching approach. J Adolesc Health 2015;56:529-535.

- Nord CW, Moore KA, Morrison DR, et al. Consequences of teen-age parenting. J Sch Health 1992;62:310-318.

- Kingston D, Heaman M, Fell D, et al. Comparison of adolescent, young adult, and adult women’s maternity experiences and practices. Pediatrics 2012;129:e1228-e1237.

- Shen J, Che Y, Showell E, et al. Interventions for emergency contraception. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2019;1:CD001324.

- Committee on Adolescence. Emergency contraception. Pediatrics 2012;130:1174-1182.

- Cleland K, Zhu H, Goldstuck N, et al. The efficacy of intrauterine devices for emergency contraception: A systematic review of 35 years of experience. Hum Reprod 2012;27:1994-2000.

- Glasier AF, Cameron ST, Fine PM, et al. Ulipristal acetate versus levonorgestrel for emergency contraception: A randomised non-inferiority trial and meta-analysis. Lancet 2010;375:555-562.

- Noon B, Dixon W. Rethinking emergency contraception. EM Resident. Published April 22, 2020. https://www.emra.org/emresident/article/emergency-contraception/

- Sayle AE, Wilcox AJ, Weinberg CR, Baird DD. A prospective study of the onset of symptoms of pregnancy. J Clin Epidemiol 2002;55:676-680.

- Guttmacher Institute. An overview of consent to reproductive health services by young people. Updated Aug 30, 2023. https://www.guttmacher.org/state-policy/explore/overview-minors-consent-law

- Jenkins A, Millar S, Robins J. Denial of pregnancy – a literature review and discussion of ethical and legal issues. J R Soc Med 2011;104:286-291.

- Miller LJ. Psychotic denial of pregnancy: Phenomenology and clinical management. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1990;41:1233-1237.

- Boyer D, Fine D. Sexual abuse as a factor in adolescent pregnancy and child maltreatment. Fam Plann Perspect 1992;24:4-11,19.

- Noll JG, Shenk CE, Putnam KT. Childhood sexual abuse and adolescent pregnancy: A meta-analytic update. J Pediatr Psychol 2009;34:366-378.

- Daley AM, Sadler LS, Reynolds HD. Tailoring clinical services to address the unique needs of adolescents from the pregnancy test to parenthood. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care 2013;43:71-95.

- Teagle SE, Brindis CD. Perceptions of motivators and barriers to public prenatal care among first-time and follow-up adolescent patients and their providers. Matern Child Health J 1998;2:15-24.

- Salas-Wright CP, Vaughn MG, Ugalde J, Todic J. Substance use and teen pregnancy in the United States: Evidence from the USDUH 2002-2012. Addict Behav 2015;45:218-225.

- Tsamantioti ES, Hashmi MF. Teratogenic medications. StatPearls. Updated Jan. 10, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK553086

- Dinwiddie KJ, Schillerstrom TL, Schillerstrom JE. Postpartum depression in adolescent mothers. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol 2018;39:168-175.

- Vigod SN, Dennis CL, Kurdyak PA, et al. Fertility rate trends among adolescent girls with major mental illness: A population-based study. Pediatrics 2014;133:e585-e591.

- Reese D. The mental health of teen moms matters. Seleni. Published 2018. https://www.seleni.org/advice-support/2018/3/14/the-mental-health-of-teen-moms-matters

- ACOG Committee Opinion No. 757: Screening for perinatal depression. Obstet Gynecol 2018;132:e208-e212.

- Everett C. Incidence and outcome of bleeding before the 20th week of pregnancy: Prospective study from general practice. BMJ 1997;315:32-34.

- Hasan R, Baird DD, Herring AH, et al. Association between first-trimester vaginal bleeding and miscarriage. Obstet Gynecol 2009;114:860-867.

- Hendriks E, MacNaughton H, Mackenzie MC. First trimester vaginal bleeding: Evaluation and management. Am Fam Physician 2019;99:166-174.

- Connolly A, Ryan DH, Stuebe AM, Wolfe HM. Reevaluation of discriminatory and threshold levels for serum beta-hCG in early pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 2013;121:65-70.

- Barnhart KT, Guo W, Cary MS, et al. Differences in serum human chorionic gonadotropin rise in early pregnancy by race and value at presentation. Obstet Gynecol 2016;128:504-511.

- Barnhart KT. Clinical practice. Ectopic pregnancy. N Engl J Med 2009;361:379-387.

- Rodgerson JD, Heegaard WG, Plummer D, et al. Emergency department right upper quadrant ultrasound is associated with a reduced time to diagnosis and treatment of ruptured ectopic pregnancies. Acad Emerg Med 2001;8:331-336.

- Doubilet PM, Benson CB, Bourne T, et al. Diagnostic criteria for nonviable pregnancy early in the first trimester. N Engl J Med 2013;369:1443-1451.

- Poulose T, Richardson R, Ewings P, Fox R. Probability of early pregnancy loss in women with vaginal bleeding and a singleton live fetus at ultra-sound scan. J Obstet Gynaecol 2006;26:782-784.

- Deutchman M, Tubay AT, Turok D. First trimester bleeding. Am Fam Physician 2009;79:985-994.

- Nanda K, Lopez LM, Grimes DA, et al. Expectant care versus surgical treatment for miscarriage. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;2012:CD003518.

- Trinder J, Brocklehurst P, Porter R, et al. Management of miscarriage: Expectant, medical, or surgical? Results of randomised controlled trial (miscarriage treatment (MIST) trial). BMJ 2006;332:1235-1240.

- Luise C, Jermy K, May C, et al. Outcome of expectant management of spontaneous first trimester miscarriage: Observational study. BMJ 2002;324:873-875.

- Kim C, Barnard S, Neilson JP, et al. Medical treatments for incomplete miscarriage. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;1:CD007223.

- Neilson JP, Hickey M, Vazquez J. Medical treatment for early fetal death (less than 24 weeks). Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006;2006:CD002253.

- Creanga AA, Shapiro-Mendoza CK, Bish CL, et al. Trends in ectopic pregnancy mortality in the United States: 1980-2007. Obstet Gynecol 2011;117:837-843.

- Clayton HB, Schieve LA, Peterson HB, et al. Ectopic pregnancy risk with assisted reproductive technology procedures. Obstet Gynecol 2006;107:595-604.

- Ankum WM, Mol BWJ, Van der Veen F, Bossuyt PM. Risk factors for ectopic pregnancy: A meta-analysis. Fertil Steril 1996;65:1093-1099.

- Bouyer J, Coste J, Shojaei T, et al. Risk factors for ectopic pregnancy: A comprehensive analysis based on a large case-control, population-based study in France. Am J Epidemiol 2003;157:185-194.

- Mol BWJ, Ankum WM, Bossuyt PMM, Van der Veen F. Contraception and the risk of ectopic pregnancy: A meta-analysis. Contraception 1995;52:337-341.

- Cheng L, Zhao WH, Zhu Q, et al. Risk factors for ectopic pregnancy: A multi-center case-control study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2015;15:187.

- Cheng L, Zhao WH, Meng CX, et al. Contraceptive use and the risk of ectopic pregnancy: A multi-center case-control study. PLoS One 2014;9:e115031.

- Hoover RN, Hyer M, Pfeiffer RM, et al. Adverse health outcomes in women exposed in utero to diethylstilbestrol. N Engl J Med 2011;365:1304-1314.

- Craig LB, Khan S. Expectant management of ectopic pregnancy. Clin Obstet Gynecol 2012;55:461-470.

- Barash JH, Buchanan EM, Hillson C. Diagnosis and management of ectopic pregnancy. Am Fam Physician 2014;90:34-40.

- Committee on Practice Bulletins–Obstetrics. Practice bulletin no. 181: Prevention of Rh D alloimmunization. Obstet Gynecol 2017;130:e57-e70.

- Goodwin TM. Hyperemesis gravidarum. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am 2008;35:401-417, viii.

- [No authors listed.] ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 153: Nausea and vomiting of pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 2015;126:e12-e24.

- Whelan LJ. Chapter 99: Comorbid Disorders in Pregnancy. In: Tintinalli JE, Stapczynski JS, Ma OJ, eds. Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide. 8th ed. McGraw-Hill;2016.

- Fell DB, Dodds L, Joseph KS, et al. Risk factors for hyperemesis gravidarum requiring hospital admission during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 2006;107(2 Pt 1):277-284.

- Giugale LE, Young OM, Streitman DC. Iatrogenic Wernicke encephalopathy in a patient with severe hyperemesis gravidarum. Obstet Gynecol 2015;125:1150-1152.

- Eroğlu A, Kürkçüoğlu C, Karaoğlanoğlu N, et al. Spontaneous esophageal rupture following severe vomiting in pregnancy. Dis Esophagus 2002;15:242-243.

- Yamamoto T, Suzuki Y, Kojima K, et al. Pneumomediastinum secondary to hyperemesis gravidarum during early pregnancy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2001;80:1143-1145.

- Friedman S, Agrawal JR. Chapter 7: Gastrointestinal & Biliary Complications of Pregnancy. In: Greenberger NJ, Blumberg RS, Burakoff R, eds. Current Diagnosis and Treatment: Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Endoscopy. 3rd ed. McGraw-Hill;2016.

- Heaton HA. Chapter 98: Ectopic Pregnancy and Emergencies in the First 20 Weeks of Pregnancy. In: Tintinalli JE, Stapczynski JS, Ma OJ, eds. Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide. 8th ed. McGraw-Hill;2016.

- Ahmed KT, Almashhrawi AA, Rahman RN, et al. Liver diseases in pregnancy: Diseases unique to pregnancy. World J Gastroenterol 2013;19:7639-7646.

- Soto-Wright V, Bernstein M, Goldstein DP, Berkowitz RS. The changing clinical presentation of complete molar pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 1995;86:775-779.

- Berkowitz RS, Goldstein DP. Current advances in the management of gestational trophoblastic disease. Gynecol Oncol 2013;1281:3-5.

This article is the first of a two-part series that focuses on an important emergency medicine topic — teenage pregnancy. In this first part, the author focuses on the unique features that affect diagnosis and management of pregnancy in adolescence. Part two will focus on obstetrical emergencies in pregnant teenagers.

Subscribe Now for Access

You have reached your article limit for the month. We hope you found our articles both enjoyable and insightful. For information on new subscriptions, product trials, alternative billing arrangements or group and site discounts please call 800-688-2421. We look forward to having you as a long-term member of the Relias Media community.