Right Upper Quadrant Pain in the ED

By Aesha Shah, MD, and Manuel Hernandez, MD, MS, MBA, CPE

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

- Etiologies of patients presenting with right upper quadrant (RUQ) abdominal pain include numerous intra-abdominal, retroperitoneal, or intrathoracic conditions.

- Evaluation of patients with RUQ abdominal pain includes a thorough history and physical, obtaining supplemental laboratory tests including complete blood count, liver function tests, and lipase and may include diagnostic imaging such as ultrasound, computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, or nuclear imaging.

- Among imaging modalities, both consultative or point-of-care ultrasound can be the initial imaging of choice because they can reliably evaluate for biliary and hepatic pathology and are readily accessible.

- Cholangitis is a highly fatal etiology of RUQ abdominal pain.

- Patients with cholangitis may present with Charcot’s triad (fever, RUQ pain, and jaundice) or Reynolds’ pentad if they also have hypotension and altered mental status.

- In patients with suspected cholecystitis or cholangitis, management with intravenous fluids, broad-spectrum antibiotics, and early surgical or gastroenterology consultation, respectively, is indicated.

- Etiologies of acute hepatitis include viral, alcoholic, autoimmune, and toxin-related.

- Patients with acute hepatitis may have a range of presentations, from mild abdominal pain and elevated liver function tests to fulminant liver failure.

- Causes of pancreatitis include alcohol, gallstones, hypertriglyceridemia, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), and medications.

- Treatment of pancreatitis is largely supportive, including intravenous fluids and pain control.

- Important intrathoracic conditions to consider in patients presenting with RUQ abdominal pain include pulmonary embolism, pneumonia, and acute coronary syndrome.

Introduction

Right upper quadrant (RUQ) abdominal pain is a frequently encountered chief complaint in the emergency department (ED) and requires methodical evaluation. Emergency physicians face the challenge of distinguishing between a broad range of potential etiologies, from benign conditions to life-threatening emergencies. This report provides a comprehensive guide for managing RUQ pain, offering insights into the pathophysiology, clinical presentations, and evidence-based approaches to diagnosis and treatment. The main goals in the assessment of RUQ abdominal pain in the emergency setting include stabilization, accurate diagnosis, and initiation of or referral for definitive care.1

Epidemiology

RUQ pain represents a significant subset of abdominal pain complaints in the emergency department. The prevalence varies widely, influenced by patient demographics, regional health trends, and common comorbidities. Biliary causes, including cholelithiasis and cholecystitis, are among the most frequently encountered conditions. Hepatic etiologies, such as hepatitis and liver abscesses, also contribute significantly. Additionally, retroperitoneal and thoracic structures as well as referred pain from other intraperitoneal structures can mimic abdominal pathology, further complicating diagnosis.2

RUQ pain occurs across a wide spectrum of ages, but presentations differ between pediatric and adult populations. For example, pediatric presentations often lack localization, necessitating a broader differential, while adults more commonly present with focal tenderness correlating to biliary or hepatic pathology.3

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of RUQ pain varies by organ system, reflecting the diverse anatomy and function of the region.4

Biliary Tract: Conditions such as gallstones or cholangitis result from obstruction or infection of the biliary ducts, leading to inflammation, ischemia, or sepsis.5

Liver: Hepatic pain may arise from parenchymal inflammation (e.g., hepatitis), abscess formation, or vascular congestion. Liver function tests often aid in distinguishing hepatic causes from other etiologies.6

Retroperitoneal Structures: The pancreas and kidneys, although located posteriorly, can cause RUQ pain due to their proximity and shared neural pathways.7

Thoracic Pathology: Referred pain to the RUQ can result from diaphragmatic irritation, pulmonary embolism, or cardiac conditions, owing to shared sensory innervation.8

A comprehensive understanding of these pathophysiological mechanisms is critical for accurately diagnosing and managing RUQ pain in the emergency department.

Etiology

Biliary Etiologies

Biliary Colic

Of all the biliary etiologies of RUQ pain, biliary colic is commonly encountered and perhaps one of the least urgent. Generally, the most common cause is gallstones causing intermittent obstruction of the biliary duct nocturnally. Occasionally, these patients present with intermittent RUQ pain with chronicity associated with dietary trigger, such as such as high fat-containing foods. Pain also can radiate to the epigastrium or right scapula with involvement of nausea, vomiting, and diaphoresis.2 Pain typically should not last more than 24 hours. Exam findings include possible positive Murphy’s sign but without peritoneal signs (rebound tenderness, guarding, or Rovsing’s sign).

Of note, another condition, sphincter of Oddi dysfunction, can present similarly to biliary colic. Unlike biliary colic, it most commonly presents after meals. Its proposed pathogenesis is currently unclear and under study, but likely caused by sphincter stenosis due to obstruction.4 Similar to biliary colic, it is a diagnosis of exclusion in the emergency department.

Acute Cholangitis

Acute cholangitis represents a potentially deadly bacterial infection of the biliary system resulting from obstruction. The classic presentation of cholangitis is that of Charcot’s triad: RUQ pain, jaundice, and fevers.2 Septic shock from ascending cholangitis also can be described by Reynolds’ pentad, which, in addition to Charcot’s triad, includes hypotension and altered mental status. Furthermore, it should be suspected in patients presenting with RUQ abdominal pain and sepsis, especially in patients with known history of pancreatic malignancy, history of choledocholithiasis, or recent history of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP).5,7 A recent retrospective study found up to a 5% incidence of acute cholangitis post-ERCP and up to a 40% risk in cases of ERCP in the setting of malignancy.7 The Tokyo Guidelines can be used as a clinical tool to increase sensitivity of diagnosis.5 (See Table 1.)

Table 1. Tokyo Guidelines for Acute Cholangitis 2018 | ||

Part A: Systemic Inflammation | Part B: Cholestasis | Part C: Imaging |

Fever and shaking/chills (38°C) | Jaundice (T-bili > 2 mg/dL) | Common bile duct dilation (> 7 mm) |

Lab evidence of inflammation (elevated/decreased WBC or elevated CRP/ESR) | Lab evidence: Abnormal liver function tests (ex: high ALT/AST) | Evidence of dilation on imaging. (ex: stricture, stone, stent, malignancy) |

Suspicion of cholangitis: One or more A plus one or more B plus C. Definitive cholangitis: one or more of A, B, and C | ||

WBC: white blood cell; CRP: C-reactive protein; ESR: erythrocyte sedimentation rate; ALT: alanine aminotransferase; AST: aspartate aminotransferase Adapted from: An Z, Braseth AL, Sahar N. Acute cholangitis: Causes, diagnosis, and management. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2021;50(2):403-414. Miura F, Okamoto K, Takada T, et al. Tokyo Guidelines 2018: Initial management of acute biliary infection and flowchart for acute cholangitis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2018;25(1):31-40. | ||

Cholangitis is one of the most emergent causes of RUQ pain. It is most commonly caused by migration of bacteria from the duodenum to the common bile duct. Typically, bacteria that ascend into the biliary tree are expulsed with bile during contraction of the gallbladder. In the setting of an obstruction from choledocholithiasis or mass, this defense mechanism is ineffective, eventually leading to bacteremia.

Acute Cholecystitis

Cholecystitis is a commonly encountered emergent pathology in patients with RUQ abdominal pain. Cholelithiasis that progresses to acute inflammation is the leading culprit for acute cholecystitis. About 10% to 15% of all patients with cholelithiasis progress to developing calculous cholecystitis.9 Acute calculous cholecystitis develops after obstruction of the cystic duct from choleliths of biliary sludge.

The risk factors for calculous cholecystitis development include female sex, obesity, rapid weight loss, oral hormonal contraceptive use, or pregnancy. In general, clinical evidence will include a positive Murphy’s sign both during exam and during sonography. RUQ pain also may refer to the right shoulder.2 Patients may have associated fevers, but typically will lack jaundice. Acalculous cholecystitis is a less common subtype.2,10 It typically is found in 5% to 10% of patients with acute disease and is caused by inflammation of the gallbladder in the absence of biliary sludge or cholelithiasis.9 Unlike calculous disease, it is more common in males. Other risk factors include critical illness, burns, diabetes, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), total or peripheral parenteral nutrition, and atherosclerosis.9,10 The Tokyo Guidelines can be used as a clinical tool to increase sensitivity of diagnosis. (See Tables 2 and 3.)

Table 2. Tokyo Guidelines for Acute Cholecysitis 2018 | ||

Part A: Local Inflammation | Part B: Systemic Inflammation | Part C: Imaging |

Positive Murphy’s sign (tenderness to palpation with inspiration in the RUQ) | Fever and shaking/chills (38°C) | Evidence of debris, pericholecystic fluid/edema, or gallbladder thickening > 3 mm on RUQ ultrasound |

RUQ mass, pain, or tenderness | Lab evidence of inflammation (elevated/decreased WBC or elevated CRP/ESR) | |

Suspicion of cholecystitis: One or more A plus one or more B plus C. Definitive cholecystitis: One or more of A, B, and C | ||

RUQ: right upper quadrant; WBC: white blood cell; CRP: C-reactive protein; ESR: erythrocyte sedimentation rate Adapted from: An Z, Braseth AL, Sahar N. Acute cholangitis: Causes, diagnosis, and management. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2021;50(2):403-414. Miura F, Okamoto K, Takada T, et al. Tokyo Guidelines 2018: Initial management of acute biliary infection and flowchart for acute cholangitis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2018;25(1):31-40. | ||

Table 3. Key Features of the Sampled Biliary Etiologies of Right Upper Quadrant Abdominal Pain | ||||

Pathology | Presentation | Lab Findings | Radiographic Findings | Treatment |

Biliary colic | Intermittent RUQ abdominal pain | Typically normal | Gallstones with secondary signs of cholecystitis | Pain control, outpatient surgical referral |

Cholecystitis | RUQ abdominal pain, + Murphy’s sign, +/- fever | Possible elevation in total bilirubin and LFTS, leukocytosis | Gallstones and +/- gallbladder distension, gallbladder wall thickening, pericholecystic fluid | IVF, IV antibiotics, surgical consultation |

Cholangitis | Charcot’s triad: Fever, RUQ pain, jaundice Reynolds’ pentad: above triad plus hypotension and AMS | Usually elevation in total bilirubin, LFTs, leukocytosis | US or CT may demonstrate dilated biliary ducts +/- air in the biliary system, +/- obstructive mass or gallstones | IVF, broad spectrum IV antibiotics, GI consultation for emergent ERCP |

RUQ: right upper quadrant; LFT: liver function tests; IVF: intravenous fluids; IV: intravenous; US: ultrasound; CT: computed tomography; GI: gastroenterology; ERCP: endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography; AMS: altered mental status | ||||

Hepatic Etiologies

Viral Hepatitis

Viral hepatitis represents hepatocellular injury of the liver caused by various viruses. Common viral hepatitis agents include hepatitis A, B, C, D, and E. The first three forms are the most common. In general, viral hepatitis should be suspected in patients with significant risk factors. For hepatitis B and C, this will be exposure to needle-stick injuries (healthcare professionals) or intravenous drug use.11 Hepatitis B and C are less likely to present acutely but pose a risk for developing hepatocellular carcinoma, which also can be a cause for RUQ pain, especially if tumor burden is causing biliary obstruction.12 Compared to hepatitis C, hepatitis B rarely can present with fulminant liver failure requiring liver transplantation. Hepatitis A, on the other hand, is more likely to present acutely. Risk factors include consumption of contaminated food or travel to an endemic region (Asia, Mexico, Africa, and South America).13 Hepatitis A typically self-resolves and does not progress to chronic disease. However, 1% of cases can present with fulminant liver failure, of which only 31% require liver transplant.11 Hepatitis D only occurs in patients with concomitant hepatitis B and can present similarly. Hepatitis E typically causes mild disease and is caused by fecal-oral transmission but can lead to critical illness in pregnant patients.

Alcoholic Hepatitis

Alcoholic hepatitis involves an acute or chronic inflammatory response in the setting of chronic alcohol use.14 In addition to the general presentation of inflammation, patients with alcoholic hepatitis may develop cirrhosis of the liver and associated complications, including esophageal variceal bleeding and hepatic encephalopathy.14,15 These individuals also may present with first time upper gastrointestinal bleeds, which can be from variceal bleeding.

Autoimmune Hepatitis

Another subtype of liver inflammation is secondary to autoimmune processes. Autoimmune hepatitis tends to affect women more than men, and the symptoms and signs can be similar to patients presenting with viral forms of hepatitis. These patients also may present with signs and symptoms of generalized inflammation, such as arthralgia or fevers.16 In addition, they may already be diagnosed with other predisposing gastroenteric disorders, such as inflammatory bowel disease.

Toxic Hepatitis

Regarding drug-induced or toxin-mediated hepatitis, there are more than 1,000 offending agents that can trigger drug-induced liver injury.17 The National Institutes of Health maintains an online database of these agents, called LiverTox.18 Internationally, the most common offending agent is amoxicillin-clavulanate (Augmentin).17 Clinicians also should consider drug-induced liver injury in patients with HIV who are on anti-retroviral therapy. Other medications frequently implicated include anti-seizure medications, amiodarone, and antidementia medications such as memantine. Other toxicities that may cause hepatitis and fulminant liver failure include acetaminophen and Amanita poison.19

Perihepatitis

Perihepatitis involves the inflammation of the hepatic capsule. Perihepatitis is also known as Fitz-Hugh-Curtis syndrome. This diagnosis should be considered as a cause of RUQ pain, especially in young sexually active females. It represents a sequela of pelvic inflammatory disease and is most associated with Chlamydia trachomatis.20 Presentation involves RUQ pain with radiation to the right shoulder, similar in presentation to cholecystitis.2

Pyogenic Liver Abscess

Hepatic abscess can be pyogenic, amebic, or fungal. Pyogenic hepatic abscesses typically are polymicrobial. Risk factors for the development of pyogenic abscess include diabetes, immunosuppression, inflammatory bowel disease, biliary disease, and recent history of a biliary procedure.21 These patients can present in a similar manner to cholangitis or with signs of sepsis. In addition, there may be pulmonary findings of crackles or dullness to percussion, suggesting a pleural effusion that is a sequela of the inflammation caused by the nearby abscess.

Amebic Liver Abscess

Amebic liver abscesses are less common in the United States and are caused by Entamoeba histolytica.22 Risk factors include immigration or travel to endemic areas: Africa, Asia, and Central and South America.21 Typically, patients with amebic abscesses present similarly to pyogenic disease and also may have concomitant watery diarrhea.2

Budd-Chiari Syndrome

Budd-Chiari syndrome, otherwise known as hepatic vein thrombosis, has the potential to become an emergent cause of acute liver failure, and ultimately patients may require transplantation. It occurs when a prothrombotic state leads to acute occlusion of the hepatic veins (outflow tract). This can lead to hepatic congestion and liver failure.23 Clinical signs include jaundice, RUQ pain, and ascites.2

Portal Vein Thrombosis

It is important to differentiate Budd-Chiari syndrome from portal venous thrombosis. Acute portal vein thrombus has varying presentations depending on the affected vessels. For example, if one of the splanchnic veins is affected, the patient may have colicky abdominal pain with diarrhea.2 One of the main risk factors for development of portal vein thrombus is cirrhosis.24

Retroperitoneal Etiologies

Pancreatitis

Acute pancreatitis can present with RUQ pain. It occurs when there is a direct obstruction of the pancreatic duct preventing enzyme release or secondary to acute inflammation of the pancreas itself. Pancreatitis frequently is caused by alcohol consumption and gallstones. It also can develop secondary to hypertriglyceridemia, as well as a complication of recent ERCP.25 Another less common etiology includes blunt abdominal trauma. The classic presentation includes persistent pain, likely in the epigastric region that can radiate to the RUQ and back. Patients also may present with nausea and vomiting. Importantly, patients may present with a severe form of pancreatitis. In these cases, there may be a mass inflammatory response that can present akin to distributive shock: hypotension and tachycardia with warm extremities.

Pancreatic Malignancy

Cancer is the most likely culprit in patients presenting with long-standing vague RUQ or epigastric pain. Patients will endorse additional history of vomiting, unintentional weight loss, or failure to thrive. Additionally, a high suspicion of malignancy should be held in patients who are older than the age of 40 years with acute pancreatitis and no other risk factors, such as alcoholism.26 These individuals also may have other concomitant bilious disease, such as cholangitis and, thus, may present with jaundice. Patients with pancreatic malignancy also may present with painless jaundice.

Nephrolithiasis

Patients with nephrolithiasis also can present with pain in the RUQ. As the stone translocates from the kidney to the ureter, leading to obstruction, the patient may have RUQ or right flank pain that may radiate to the right lower quadrant or right groin. Patients may present with severe, sudden onset of right flank or RUQ pain. The pain associated with obstructive nephrolithiasis typically is colicky and intermittent. These patients often have associated dysuria and hematuria. Almost 50% of cases of obstructive nephrolithiasis will involve nausea and vomiting.27 On physical exam, patients may have costovertebral angle (CVA) tenderness and, less commonly, RUQ pain and/or right lower quadrant tenderness to palpation.

Pyelonephritis

Infection of the kidneys may present with RUQ or right flank pain. Patients with pyelonephritis may have associated dysuria, fever, nausea, and vomiting.28 Pyelonephritis also can lead to sepsis and complications such as renal abscess.

Thoracic Etiologies

Pulmonary Embolism

One of the more commonly missed diagnoses in the emergency department, pulmonary embolism (PE) is a potentially emergent cause of RUQ pain. Patients can present with pleuritic chest pain and pain during inspiration. Furthermore, patients can have referred pain to the RUQ, particularly if there is an associated pulmonary infarct. In addition, patients may have symptoms of dyspnea and cough.29 They also may have calf swelling or pain if there was a preceding deep vein thrombosis. The most common vital sign abnormality seen in patients with PE includes tachycardia.29 Hypotension also can be present if there is large thrombus causing significant strain to the right side of the heart.

Pneumonia

Acute pneumonia can cause inflammation in the lung parenchyma, resulting in diaphragmatic irritation.30 This can lead to acute pain to the RUQ. Patients with pneumonia typically will present with concomitant infectious complaints, such as cough and fever, and may have associated chest pain and shortness of breath. Other associated symptoms may include nausea and pain or post-tussive-induced vomiting. Finally, on physical exam patients may present with crackles during lung auscultation. In addition, vital signs may vary from normal to those consistent with sepsis and septic shock, including hypoxia.

Other Potential Causes

Understanding the myriad of structures and organ systems in the thoracoabdominal cavity, there are a number of other diagnoses that less commonly can present with RUQ pain as a presenting symptom. These include, but are not limited to: acute coronary syndrome, appendicitis, diaphragmatic injury, intra-abdominal ectopic pregnancy, and mesenteric ischemia/infarction.

Evaluation

Laboratory Studies

Laboratory studies are a cornerstone in the evaluation of RUQ pain, providing critical insights into potential diagnoses. While a wide variety of laboratory studies may be useful in the evaluation of RUQ abdominal pain, it is important to focus laboratory diagnostics based on the patient’s history, physical examination, relevant history, and corresponding differential diagnosis. This section discusses common laboratory tests and highlights expected findings associated with specific conditions.

Complete Blood Count

The complete blood count (CBC) frequently is ordered to assess for signs of infection, anemia, or other hematologic abnormalities. Leukocytosis is a common finding in acute cholecystitis and cholangitis, as well as other infectious processes. The presence of anemia may indicate gastrointestinal bleeding or chronic liver disease in the appropriate clinical setting.

Liver Function Tests and Coagulation Studies

Liver function tests (LFTs) help evaluate hepatic and biliary function by measuring serum levels of bilirubin, transaminases, and alkaline phosphatase. Elevated alkaline phosphatase and bilirubin are suggestive of biliary involvement, including infection, inflammation, obstruction, and/or cholangitis. Elevated alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) are indicative of hepatocellular injury, as seen in viral hepatitis or toxic hepatitis. In instances of advanced liver disease with considerable liver damage, liver enzymes may appear to be within or below the reference range. In these instances, a prolonged prothrombin time may be present, suggesting advanced damage and disease progression as the liver loses its synthetic function.

Lipase

Pancreatic enzymes are critical for diagnosing acute pancreatitis. Key findings include elevated amylase and lipase. Lipase is more specific to pancreatic injury and has become the gold standard laboratory test to assess for pancreatic inflammation or injury. Mild elevations in lipase also may occur in biliary obstruction. As in the case of advanced hepatic injury, patients with severe chronic pancreatitis or other forms of pancreatic disease causing severe pancreatic damage may result in the patient presenting with clinical findings suggestive of pancreatic inflammation or damage without evidence of an elevated lipase.

Inflammatory Markers

C-reactive protein (CRP) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) are nonspecific markers of inflammation. Elevated CRP and ESR are indicative of infection or inflammatory conditions, such as cholecystitis or hepatitis. Since CRP and ESR are nonspecific inflammatory markers, they tend to have limited value in the acute setting. However, they may add value for ongoing evaluation and monitoring of broader disease processes

Hepatitis Panel

A hepatitis panel helps identify viral hepatitis and includes serologic markers for hepatitis A, B, and C. Positive anti-hepatitis A virus (HAV) immunoglobulin M (IgM) suggests acute hepatitis A infection, hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) positivity indicates chronic hepatitis B infection, and a positive HBsAg with a positive anti-hepatitis B virus (HBV) core IgM represents acute hepatitis B. Anti-hepatitis C virus (HCV) antibodies suggest acute or chronic hepatitis C. Confirmatory ribonucleic acid (RNA) testing is required to diagnose hepatitis C. (See Table 4.)

Table 4. Laboratory Assessment and Interpretation in the Evaluation of Viral Hepatitis | ||||

Anti-hepatitis A, IgM | Hepatitis B surface antigen | Anti-hepatitis B core, IgM | Anti-hepatitis C | Clinical Significance |

+ | – | – | – | Acute hepatitis A |

– | + | + | – | Acute hepatitis B |

– | + | – | – | Chronic hepatitis B |

– | – | – | + | Possible acute or chronic hepatitis C** |

**Needs confirmatory testing with hepatitis C virus polymerase chain reaction as a positive test can represent a prior cleared infection or a false positive IgM: immunoglobulin M Adapted from: Ostapowicz G, Fontana RJ, Schiodt FV, et al. Results of a prospective study of acute liver failure at 17 tertiary care centers in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137(12):947-954. | ||||

Additional Laboratory Studies to Consider

Depending on the clinical scenario, additional laboratory studies may be indicated, including:

Urinalysis: This test is helpful in diagnosing urinary etiologies, such as infectious and obstructive pathologies. It also is useful in identifying dehydration, as demonstrated by elevated specific gravity and ketone levels.

Pregnancy Test: A pregnancy test should be ordered in all biologically female patients of child-bearing age. It is important for consideration of intra-abdominal ectopic pregnancy or ruptured ectopic pregnancy. Pregnancy testing also is useful to support shared decision-making with respect to imaging modalities and potential radiation exposure.

D-Dimer: Another inflammatory marker, D-dimer is useful for the evaluation of suspected pulmonary embolism.

Cardiac Enzymes: Cardiac enzymes should be included when the patient’s history and presentation suggest that acute coronary syndrome cannot be excluded.

Blood Cultures and Lactic Acid: These tests are essential for the management of obvious or suspected sepsis. Elevated lactic acid levels suggest a more severe infectious process with corresponding physiologic impact.

Imaging and Diagnostic Modalities

Imaging and diagnostic modalities are integral to the evaluation of many causes of RUQ pain, providing essential data to guide diagnosis and management. The choice of imaging modality should be tailored to the patient’s clinical presentation and suspected diagnosis. This section reviews key imaging modalities, highlighting their applications, limitations, and expected findings.

Ultrasound

Ultrasound is the first-line imaging modality for evaluating RUQ pain. It is particularly useful for biliary pathologies, including cholelithiasis, choledocholithiasis, and acute cholecystitis. Key diagnostic findings seen on ultrasound in the setting of biliary disease include gallstones, gallbladder wall thickening (> 3 mm), pericholecystic fluid, and a positive sonographic Murphy’s sign. A dilated common bile duct (> 7 mm) and/or a hydropic gallbladder also can represent distal obstruction from a stone or mass.2,9 (See Figures 1-3.)

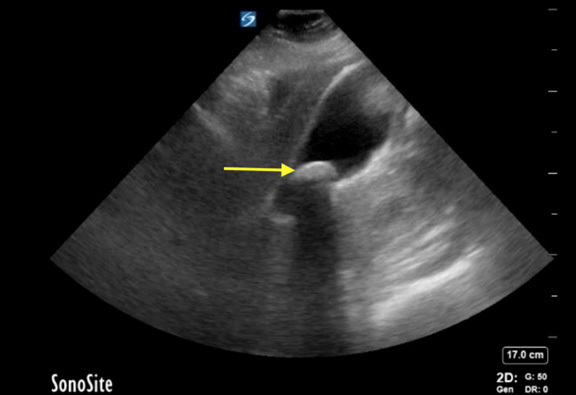

Figure 1. Cholelithiasis in the Gallbladder |

Presence of cholelithiasis within the gallbladder (yellow arrow). Note the posterior acoustic shadowing of the stones. |

|

Image courtesy of Daniel Migliaccio, MD, FPD, FAAEM. |

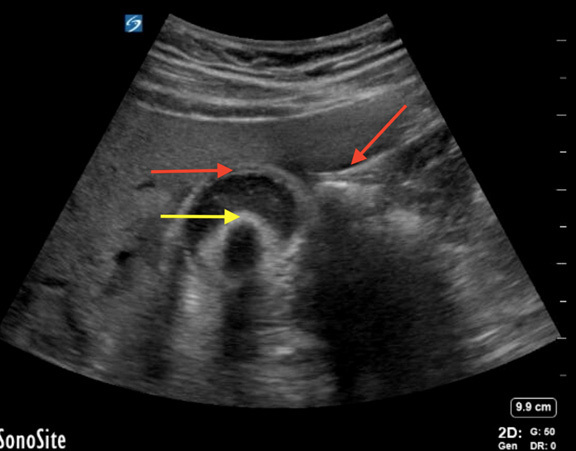

Figure 2. Cholecystitis |

Cholecystitis evidenced by gallstone (yellow arrow) wall thickening with pericholecystic fluid (red arrows). Sludge also is present inside the gallbladder. |

|

Image courtesy of Daniel Migliaccio, MD, FPD, FAAEM. |

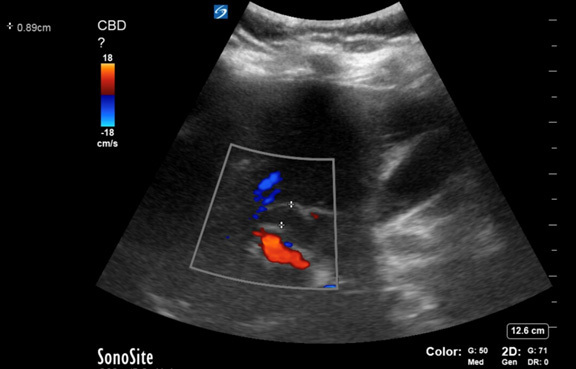

Figure 3. Cholangitis Resulting from Biliary Obstruction |

Evidence of dilated common bile duct measuring at 0.89 cm in a case of cholangitis resulting from biliary obstruction. Note the common bile duct is sitting above the hepatic artery. |

|

Image courtesy of Daniel Migliaccio, MD, FPD, FAAEM. |

A recent review suggests starting with an ultrasound of the RUQ to evaluate for common bile duct dilation. Dilation > 7 mm is indicative of acute obstruction. Ultrasound has a specificity of nearly 100%, although its sensitivity is only 38%.2,5 This variability is largely due to differences in technician skill. Another limitation of ultrasound is reduced efficacy in patients with a high body mass index (BMI) because of increased tissue depth and sound wave scattering.31

In cases where ultrasound findings are equivocal and there is ongoing concern for bile duct obstruction, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) or ERCP may be indicated for further evaluation and treatment.7 Despite its limitations, ultrasound is cost-effective and readily available, making it a primary tool in the emergency department.

Computed Tomography

Computed tomography (CT) scans provide detailed cross-sectional and three-dimensional reconstructed imaging, making CT valuable for detecting possible etiologies of RUQ pain. While less sensitive than ultrasound for biliary pathology, CT is more effective in identifying alternative or complicated diagnoses, such as pancreatitis, abscesses, or perforations.2

CT imaging with intravenous contrast enhances visualization of vascular structures and inflammation. Sensitivity for cholecystitis approaches 96%, although specificity is lower at 56%.9,10 This makes CT a reasonable option for patients with generalized abdominal pain or obesity, where ultrasound may be less effective.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) offers superior soft tissue contrast and is particularly useful for evaluating complex hepatic or biliary conditions. MRCP is a specialized technique that provides noninvasive visualization of the biliary tree and pancreatic ducts. Findings may include bile duct obstruction, strictures, or masses.3

Although MRI is not commonly used as a first-line imaging modality because of its cost and availability, it is playing an emerging and growing role in select cases requiring detailed anatomical evaluation.

Nuclear Medicine Studies

Nuclear medicine studies, such as hepatobiliary iminodiacetic acid (HIDA) scans, assess bile flow and gallbladder function. HIDA scans are particularly sensitive and specific (both > 90%) for diagnosing acute cholecystitis. Findings include non-visualization of the gallbladder, delayed emptying, or obstruction.2,9

While HIDA scans are the most accurate imaging modality for biliary pathologies, they also are the most expensive and time-consuming and not always readily available in the ED setting. As such, HIDA scans typically are reserved for cases with high clinical suspicion and nondiagnostic results from other modalities.

Point-of-Care Ultrasound (POCUS)

Point-care-ultrasound (POCUS) is a tool used by emergency medicine providers in aiding clinical decision-making. One such utility of POCUS is evaluating RUQ pain. The use of POCUS has numerous benefits, including its accessibility, low cost, and immediate insight into a patient’s presentation leading to rapid decision-making. One cohort study found that POCUS had a statistically significant improvement in developing a differential diagnosis and ordering complementary testing in patients with RUQ abdominal pain.32 Furthermore, it highlighted the benefits of a protocolized process for POCUS for RUQ pain. Another study also showed that there were statistically significant similarities in the quality of POCUS studies completed by emergency medicine physicians when compared to radiology technicians.33 Potential limitations of POCUS include patient factors, such as bowel gas and increasing body mass index (BMI), and provider factors, such as a lack of training or skill, leading to inadequate image acquisition.33

Key Applications and Diagnostic Findings

POCUS is widely used in the ED for evaluating RUQ pain, with specific applications including:

Gallstones: Identification of hyperechoic foci with posterior acoustic shadowing.

Biliary Obstruction: Common bile duct dilation (> 7 mm) indicates obstruction, with a specificity close to 100% but a sensitivity of only 38%.2,5

Acute Cholecystitis: Identification of gallbladder wall thickening (> 3 mm), pericholecystic fluid, gallstones, and a positive sonographic Murphy’s sign are hallmark findings. Air within the gallbladder wall may suggest emphysematous cholecystitis.

Free Fluid: Rapid detection of intraperitoneal fluid in the context of trauma or rupture.

Hepatic Abscess: Hypoechoic or complex fluid collections may be identified in cases of pyogenic liver abscess.

Management

General Principles

Management of RUQ pain in the emergency department prioritizes stabilization, accurate diagnosis, and timely initiation of treatment or referral for definitive care. The approach is guided by the underlying etiology, clinical presentation, and patient-specific factors, such as age, comorbidities, and hemodynamic stability. Across all conditions, the goals are to alleviate symptoms, address the underlying cause, and prevent complications. Treatment frequently involves a multidisciplinary team including emergency physicians, surgeons, gastroenterologists, and intensivists.

Biliary Causes

Biliary Colic: Management in the emergency department focuses on symptom control and patient education. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or acetaminophen can be sufficient for pain relief in patients with biliary colic. Patients with biliary colic should receive a referral to a general surgeon for a discussion of the options for management, including the possibility of an elective cholecystectomy. Patients should be advised to avoid dietary triggers, such as high-fat meals, and given strict return precautions for biliary obstruction.2,3

Acute Cholangitis: Acute cholangitis is a life-threatening condition requiring prompt intervention. Initial management involves:

- Antibiotic Therapy: Empirical broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics targeting streptococci, Enterobacteriaceae, and anaerobes are standard. Coverage may include piperacillin-tazobactam or a combination of cefepime with metronidazole. In healthcare-associated cases, antipseudomonal coverage is recommended.2,5,7

- Biliary Drainage: The provider should obtain an emergent consultation with a gastroenterologist for coordination of ERCP. ERCP is the treatment modality of choice for decompression of the biliary tree.7

- Supportive Care: Intravenous fluids and hemodynamic support are critical in septic patients. Ultimate disposition involves admission for continued care and consideration of interval cholecystectomy to prevent recurrence. Mortality rates vary significantly based on severity, ranging from 2% to 65%.6

Acute Cholecystitis: Patients with acute cholecystitis require early surgical consultation. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy within 24 to 48 hours of symptom onset is associated with better outcomes, including reduced mortality and surgical complications. Antibiotic therapy targets similar organisms as acute cholangitis. In critically ill patients unable to undergo surgery, percutaneous cholecystostomy may be performed as a temporizing measure.2,10,34

Hepatic Causes

Viral Hepatitis: Management of viral hepatitis depends on severity. Stable patients with mild symptoms are treated with supportive care, including hydration and antiemetics. Fulminant hepatic failure necessitates transfer to a facility with liver transplant capabilities. In pediatric cases of hepatitis A, immunoglobulin may be administered to mitigate disease progression.11

Alcoholic Hepatitis: Treatment includes supportive care, correction of coagulopathies, and management of alcohol withdrawal. Corticosteroids or pentoxifylline may be considered for severe cases, although their efficacy remains debated. Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP) should be suspected and treated empirically in patients with ascites. When possible, patients with ascites and concern for SBP should have a diagnostic paracentesis performed to analyze the ascitic fluid for infection.14,15

Autoimmune and Toxic Hepatitis: Autoimmune hepatitis may be managed with corticosteroids and hepatology consultation. Toxin-induced hepatitis typically requires cessation of the offending agent and administration of specific antidotes, such as N-acetylcysteine for acetaminophen toxicity.2,17

Pyogenic Liver Abscess: Initial treatment of pyogenic hepatic abscess involves broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics, often covering gram-negative rods, streptococci, and anaerobes. Percutaneous drainage typically is recommended for abscesses larger than 3 cm. Surgical consultation is warranted for suspected abscess rupture or peritonitis.21,22

Amebic Liver Abscess: Metronidazole is the first-line treatment in patients with amebic hepatic abscess, with most cases resolving with oral therapy alone. Patients unresponsive to medical therapy may require surgical drainage.21,22

Retroperitoneal Causes

Acute Pancreatitis: Management includes aggressive fluid resuscitation, pain control, and antiemetics. Antibiotics are reserved for confirmed infected necrosis or concomitant sepsis. Patients with gallstone pancreatitis may necessitate ERCP for stone removal.25

Nephrolithiasis: Pain control is paramount, typically achieved with NSAIDs and/or opioids. Alpha-blockers, such as tamsulosin, may facilitate stone passage in distal ureteral stones smaller than 10 mm. Surgical intervention, such as ureteral stent placement, is indicated for obstructive stones causing sepsis or significant renal impairment.27,35

Pyelonephritis: Patients with uncomplicated pyelonephritis often can be managed as outpatients with oral antibiotics. Hospital admission for intravenous antibiotics is indicated for patients with severe symptoms, significant comorbidities, or pregnancy.28

Thoracic Causes

Pulmonary Embolism: Initial treatment includes anticoagulation with low molecular weight heparin or direct oral anticoagulants. Hemodynamically unstable patients may require thrombolysis or surgical embolectomy. Outpatient management may be appropriate for low-risk patients.36

Pneumonia: Management involves empiric antibiotic therapy targeting common pathogens, including atypical bacteria. Supplemental oxygen is provided as needed. Admission is warranted for patients with respiratory compromise, significant comorbidities, or immunosuppression.30

Special Populations

Pregnancy

The management of RUQ pain during pregnancy requires consideration of both maternal and fetal well-being. Several conditions unique to or influenced by pregnancy must be evaluated carefully.

Acute Cholecystitis: Laparoscopic cholecystectomy is recommended in any trimester for pregnant patients with acute cholecystitis. Delaying surgery increases the risk of maternal and fetal complications, including preterm labor and sepsis.37,38

HELLP Syndrome: In pregnancy, hepatic manifestation of preeclampsia also should be considered as a cause for RUQ pain. This is called HELLP syndrome, which stands for hemolysis, elevated transaminases (liver enzymes), and thrombocytopenia.38 It typically presents with epigastric or RUQ pain, fatigue, and malaise, with possible jaundice.2 These patients are usually between 28-37 weeks of gestation.38 Patients typically will present with associated hypertension and proteinuria, similar to preeclampsia.2 CBC may reveal anemia and thrombocytopenia from a microangiopathic hemolysis.38 Finally, transaminases can be as high as double the upper limit of normal.38 In the emergency department, treatment should focus on blood pressure control, provision of magnesium sulfate for seizure prophylaxis, and repletion of red blood cells and platelets as needed.2,38 Ultimately, obstetrics should be consulted for disposition planning and definitive management, which may include fetal delivery.17,19

Intrahepatic Cholestasis of Pregnancy (ICP): ICP presents with RUQ pain and pruritus due to elevated bile acids. Treatment focuses on reducing bile acid levels with ursodeoxycholic acid and early delivery for severe cases. Maternal-fetal medicine specialists should guide care.9

Pediatrics

RUQ pain in pediatric patients often is challenging to diagnose because of nonspecific symptoms and limited communication abilities. Age-specific etiologies must be considered, including:

Biliary Atresia: This congenital condition presents in neonates and infants with jaundice and acholic stools. Surgical intervention (Kasai procedure) within the first two months of life has been demonstrated to improve outcomes.40,41

Intussusception: Although it commonly causes colicky abdominal pain, intussusception may present with RUQ tenderness. Diagnosis is confirmed with ultrasound, and air or barium enema reduction typically is curative. In severe or recurrent cases, surgical intervention may be required.42

Acute Viral Hepatitis: Viral hepatitis, often caused by hepatitis A, is a common cause of pediatric RUQ pain. Management includes supportive care, hydration, and monitoring for complications.11

Older Adults

Older adults presenting with RUQ pain often have atypical or subtle symptoms, complicating diagnosis and treatment. Important considerations include:

Acute Cholecystitis: Older adult patients are at increased risk of severe complications, including perforation and sepsis. Early surgical intervention is critical for reducing morbidity and mortality.10

Hepatic Abscesses: Symptoms may be vague in older adults, leading to delayed diagnosis. Imaging studies and broad-spectrum antibiotics are essential components of care. Percutaneous drainage may be necessary for abscesses larger than 3 cm.22

Ischemic Hepatitis: This condition is more common in older adult patients with preexisting cardiovascular conditions. Management focuses on addressing the underlying ischemic event and supportive care.14,20

Immunocompromised Patients

Patients with immunosuppression due to HIV/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), organ transplantation, or chemotherapy require specialized evaluation and management of RUQ pain:

Opportunistic Infections: Pathogens such as cytomegalovirus (CMV) or fungal infections should be considered in immunocompromised patients presenting with hepatic or biliary involvement. Empiric antifungal or antiviral therapy may be initiated while awaiting diagnostic confirmation.33,43

Cholangitis: Patients with biliary obstruction are at increased risk of rapidly progressing cholangitis. Prompt antibiotic therapy and biliary decompression via ERCP are critical.7

Medication Toxicity: Hepatotoxicity from medications, such as chemotherapy agents or antiretrovirals, should be considered. Management includes discontinuing the offending agent and initiating supportive care.32

Conclusion

RUQ pain is a common yet complex presentation in the emergency department, encompassing a wide range of potential etiologies, from benign conditions to life-threatening emergencies. Effective management of RUQ pain requires a systematic approach grounded in a thorough understanding of anatomy, pathophysiology, and evidence-based diagnostic and therapeutic strategies.

Early recognition and stabilization of critically ill patients are paramount, followed by targeted diagnostic studies tailored to the clinical scenario. Laboratory tests, imaging modalities, and POCUS play complementary roles in narrowing the differential diagnosis and guiding management decisions. Treatment should address the underlying cause, alleviate symptoms, and mitigate complications, often necessitating a multidisciplinary team approach.

Special populations, including pregnant women, children, older adults, and immunocompromised individuals, require tailored evaluation and management strategies to optimize outcomes. Understanding the unique challenges and nuances of these populations enhances the clinician’s ability to deliver the most appropriate care. It is critical for the emergency clinician to have a thorough understanding of the various pathologies that can present with RUQ abdominal pain.

Aesha Shah, MD, is Resident Physician, Department of Emergency Medicine, Penn State Hershey Medical Center, Hershey, PA.

Manuel Hernandez, MD, MS, MBA, CPE, is Assistant Professor, Department of Emergency Medicine, Penn State Health — Milton S. Hershey Medical Center, Hershey, PA.

References

1. Eltyeb HA, Al-Leswas D, Abdalla MO, Wayman J. Systematic review and meta-analyses of cholecystectomy as a treatment of biliary hyperkinesia. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2021;14(5):1308-1317.

2. Napolitano LM, Alam HB, Biesterveld BE, et al. Evaluation and Management of Gallstone-Related Diseases in Non-Pregnant Adults [Internet]. Michigan Medicine University of Michigan; 2021 Dec.

3. Latenstein CSS, de Reuver PR. Tailoring diagnosis and treatment in symptomatic gallstone disease. Br J Surg. 2022;109(9):832-838.

4. Villavicencio Kim J, Wu GY. Update on sphincter of Oddi dysfunction: A review. J Clin Transl Hepatol. 2022;10(3):515-521.

5. An Z, Braseth AL, Sahar N. Acute cholangitis: Causes, diagnosis, and management. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2021;50(2):403-414.

6. Kimura, Y, Takada T, Kawarada Y, et al. Definitions, pathophysiology, and epidemiology of acute cholangitis and cholecystitis: Tokyo Guidelines. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 2007;14:15-26

7. Ahmed M. Acute cholangitis — an update. World J Gastrointest Pathophysiol. 2018;9(1):1-7.

8. Virgile J, Marathi R. Cholangitis. In: StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Updated July 4, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK558946/

9. Gallaher JR, Charles A. Acute cholecystitis: A review. JAMA. 2022;327(10):965-975.

10. Abdulrahman R, Hashem J, Walsh TN. A review of acute cholecystitis. JAMA. 2022;328(1):76-77.

11. Castaneda D, Gonzalez AJ, Alomari M, et al. From hepatitis A to E: A critical review of viral hepatitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2021;27(16):1691-1715.

12. Pisano MB, Giadans CG, Flichman DM, et al. Viral hepatitis update: Progress and perspectives. World J Gastroenterol. 2021;27(26):4018-4044.

13. Jouanguy E. Human genetic basis of fulminant viral hepatitis. Hum Genet. 2020;139(6-7):877-884.

14. Sehrawat TS, Liu M, Shah VH. The knowns and unknowns of treatment for alcoholic hepatitis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5(5):494-506.

15. Gougol A, Clemente-Sanchez A, Argemi J, Bataller R. Alcoholic hepatitis. Clin Liver Dis (Hoboken). 2021;18(2):90-95.

16. Komori A. Recent updates on the management of autoimmune hepatitis. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2021;27(1):58-69.

17. Tan CK, Ho D, Wang LM, Kumar R. Drug-induced autoimmune hepatitis: A minireview. World J Gastroenterol. 2022;28(24):2654-2666.

18. LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury [Internet]. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2012-. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK547852/

19. Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed®) [Internet]. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development; 2006–. Amanita Mushroom Poisoning. Last revision: June 14, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK532496/

20. Basit H, Pop A, Malik A, Sharma S. Fitz-Hugh-Curtis Syndrome. In: StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Updated Feb. 8, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK499950/

21. Sharma S, Ahuja V. Liver abscess: Complications and ttreatment. Clin Liver Dis (Hoboken). 2021;18(3):122-126.

22. Roediger R, Lisker-Melman M. Pyogenic and amebic infections of the liver. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2020;49(2):361-377.

23. Hitawala AA, Gupta V. Budd-Chiari Syndrome. In: StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan–. Updated Jan. 30, 2023.

24. Senzolo M, Garcia-Tsao G, García-Pagán JC. Current knowledge and management of portal vein thrombosis in cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2021;75(2):442-453.

25. Tenner S, Vege SS, Sheth SG, et al. American College of Gastroenterology Guidelines: Management of acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2024;119(3):419-437.

26. Kim HS, Gweon TG, Park SH, et al. Incidence and risk of pancreatic cancer in patients with chronic pancreatitis: Defining the optimal subgroup for surveillance. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):106.

27. Song L, Maalouf NM. Nephrolithiasis. In: Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Blackman MR, et al, eds. Endotext [Internet]. MDText.com, Inc.; 2000-. Last update: March 9, 2020. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK279069/

28. Belyayeva M, Leslie SW, Jeong JM. Acute Pyelonephritis. In: StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Updated Feb. 28, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK519537/

29. Stein PD, Beemath A, Matta F, et al. Clinical characteristics of patients with acute pulmonary embolism: Data from PIOPED II. Am J Med. 2007;120(10):871-879.

30. Bajaj SK, Tombach B. Respiratory infections in immunocompromised patients: Lung findings using chest computed tomography. Radiol Infect Dis. 2017;4(1):29-37.

31. Maar M, Lee J, Tardi A, et al. Inter-transducer variability of ultrasound image quality in obese adults: Qualitative and quantitative comparisons. Clin Imaging. 2022;92:63-71.

32. Dupriez F, Niset A, Couvreur C, et al. Evaluation of point-of-care ultrasound use in the diagnostic approach for right upper quadrant abdominal pain management in the emergency department: A prospective study. Intern Emerg Med. 2024;19(3):803-811.

33. Miravent S, Lobo M, Figueiredo T, et al. Effectiveness of ultrasound screening in right upper quadrant pain: A comparative study in a basic emergency service. Health Sci Rep. 2023;6(5):e1251.

34. Loozen CS, Kortram K, Kornmann VN, et al. Randomized clinical trial of extended versus single-dose perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis for acute calculous cholecystitis. Br J Surg. 2017;104(2): e151-e157.

35. Furyk JS, Chu K, Banks C, et al. Distal ureteric stones and tamsulosin: A double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized, multicenter trial. Ann Emerg Med. 2016;67(1):86-95.e2.

36. Vyas V, Sankari A, Goyal A. Acute Pulmonary Embolism. In: StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Updated Feb. 28, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK560551/

37. Zachariah SK, Fenn M, Jacob K, et al. Management of acute abdomen in pregnancy: Current perspectives. Int J Womens Health. 2019;11:119-134.

38. Khalid F, Mahendraker N, Tonismae T. HELLP Syndrome. In: StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Updated June 16, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK560615/

39. Chou A. Austin RL. Entamoeba histolytica Infection. In: StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Updated May 3, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557718/

40. Lee WH, O’Brien S, Skarin D, et al; PREDICT. Pediatric abdominal pain in children presenting to the emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2021;37(12):593-598.

41. Zhang M, Zhou X, Hu Q, Jin L. Accurately distinguishing pediatric ileocolic intussusception from small-bowel intussusception using ultrasonography. J Pediatr Surg. 2021;56(4):721-726.

42. Okamoto K, Suzuki K, Takada T, et al. Tokyo Guidelines 2018: Flowchart for the management of acute cholecystitis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2018;25(1):55-72. Erratum in: J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2019;26(11):534.

43. Cartwright SL, Knudson MP. Evaluation of acute abdominal pain in adults. Am Fam Physician. 2008;77(7):971-978.

Right upper quadrant abdominal pain is a frequently encountered chief complaint in the emergency department and requires methodical evaluation. Emergency physicians face the challenge of distinguishing between a broad range of potential etiologies, from benign conditions to life-threatening emergencies.

Subscribe Now for Access

You have reached your article limit for the month. We hope you found our articles both enjoyable and insightful. For information on new subscriptions, product trials, alternative billing arrangements or group and site discounts please call 800-688-2421. We look forward to having you as a long-term member of the Relias Media community.