Recognizing, Managing, and Reporting Pediatric Sexual Abuse and Assault

Authors

Lori D. Frasier, MD, Professor of Pediatrics, Penn State Hershey Medical Center, Penn State Hershey College of Medicine

Stephen M. Sandelich, MD, Pediatric Emergency Medicine, Penn State Health Children’s Hospital, Hershey, PA

Peer Reviewer

Steven M. Winograd, MD, FACEP, Attending Emergency Physician, Trinity Health Care, Samaritan, Troy, NY

Executive Summary

- Abuse of children and adolescents occurs across the societal spectrum. Most sexual abuse is perpetrated on children by someone in the family or who is well known to the child and family.

- Open-ended questions are the most forensically sound way to obtain information from a child. Open-ended questions require narrative responses. “Can you tell me why you came to the hospital today?”

- Documentation of the questions and answers should be detailed and documented in the child’s own words.

- Adolescents should be provided with the rules of disclosure to the clinician prior to asking sensitive questions. Trust can be established only if the adolescent understands what can and cannot be disclosed to the authorities and to their parents.

- More than 30 years of research have demonstrated that the most common findings in child sexual abuse are normal findings.

- The most important reason for an examination to be done in the emergency department (ED) is to exclude acute trauma or injury to the anogenital area. Collection of forensics in prepubertal children is highly specialized and should be done by someone with experience or via referral to a center with experienced professionals.

- The use of expertise in the evaluation of child sexual abuse is critical. Many children’s hospitals will have child abuse pediatricians and child protection teams that are highly trained and experienced in the evaluation of all aspects of child and adolescent sexual abuse and assault.

- Examinations in children who have no symptoms of pain or bleeding or in whom there is no support for evidence collection can have their examinations deferred to a specialized clinic or children’s advocacy center (CAC) without the loss of evidence.

- Sexually transmitted infection prophylaxis of prepubertal children is not recommended.

- Follow-up in a specialized clinic or CAC with specially trained providers is critical. Each ED provider should know the resources in their communities for this follow-up.

Child sexual abuse is a common concern for patients presenting to the emergency department. The approach depends not only on the age and development of the child, but also the allegations, time since the contact occurred, and the child's symptoms. It is imperative that all clinicians are familiar with the optimal approach and evaluation of a child with alleged sexual abuse.

— Ann M. Dietrich, MD, FAAP, FACEP, Editor

Definition of the Problem

Child sexual abuse is a common concern among children and adolescents presenting to the emergency department (ED), and it is important that clinicians have a broad understanding of the ED’s role in evaluating child sexual abuse. There are different approaches to children with a concern of sexual abuse that depend upon the age and development of the patient, the type of allegations, the time since the alleged contact, and any symptoms or injuries with which the child presents. This review will present an approach to the child or adolescent presenting to the ED.

Epidemiology

Child sexual abuse is, unfortunately, a common problem. It is estimated that one in three girls and one in eight to 10 boys are sexually abused or exploited online prior to the age of 18 years.1 This information comes from retrospective recollections by adults.

These data included a broad definition of child sexual abuse that ranged from violent penetrative rape to many other acts of a sexual nature — as well as online sexual exploitation. Other data come from the National Child Abuse and Neglect Data System (NCANDS). NCANDS is a voluntary data collection system from all 50 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico regarding reports of child abuse and neglect in these jurisdictions. The most recent data from NCANDS in 2022 indicate that there were approximately 4.2 million reports involving more than 7 million children. The national estimate of victims of child abuse is around 600,000, with an estimated 10% referring to sexual abuse.2 The number of children (younger than 18 years of age) in the United Sates is estimated to be ~73 million split roughly equally between males and females.

The proportion of girls potentially sexually abused would be around 10 million, and the number of sexually abused boys would be around 3 million. The gap is obvious — far fewer children come to the attention of child protective authorities than likely are abused. Alternatively, the retrospective data may overestimate the rates. The issues remain complex. However, mandatory reporting of suspected child abuse is required in every state and territory of the United States. Despite that, many children never come to care. Those who do come to care in EDs likely represent a small percentage of children who actually are subject to sexual abuse.

Etiology

The underlying reasons that children and adolescents are sexually abused vary greatly. The types of sexual contact also vary and have different definitions within the legal systems of every state. Abuse of children and adolescents occurs across the societal spectrum. Most sexual abuse is perpetrated on children by someone in the family or who is well known to the child and family.3

Stranger sexual assault of children, although serious and frightening, constitutes (at most) 10% of all sexual abuse.3

Adolescents may be at risk for sexual abuse or assault because of peer pressure and hormonal changes. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer and/or questioning children are more at risk for sexual assault and abuse.4 It is important to report only facts and not make judgments of who may or may not have sexually abused a child or why an adolescent may have been sexually assaulted. The medical care team always should provide compassionate, supportive care and let law enforcement or Child Protective Services (CPS) determine the source of the events.

Clinical Features

Parents present a child to the ED with a concern for sexual abuse for many reasons. The child may have disclosed an event that happened recently or in the past. There may be concerns about genital or anal symptoms that could be the result of sexual contact or an unrelated medical condition.

Parents’/caregivers’ concerns are real. They are fearful that their child has been harmed. The physician’s role is to remain compassionate but objective when approaching the issue. The following section will be categorized by several aspects of this evaluation depending upon the age development and circumstances of the child’s presentation.

General History

Taking a history from a parent or child victim of sexual abuse can be concerning for the clinicians. There is a fear that asking too many questions will somehow contaminate subsequent history. Meanwhile, there is a concern that not getting sufficient information may not allow adequate reporting and protection of a child. Evaluating the validity of any history is difficult because there are concerns from parents as well as a direct history from a child.

The ability of a child to provide their own history is based upon developmental as well as social factors. Children who are groomed by sexual perpetrators may be fearful of the consequences of disclosure. Some children may be coerced to give false histories. It is not the purview of the clinician in the ED to determine whether information is true or accurate. The clinician reports what the child said, how they said it, and how the questions were asked.

Preverbal Children

This age group cannot give an independent history. The clinician is reliant on the parent or caregiver to provide all of the information. It is important that the ED clinician reports the historian by name and relationship to the child who is providing that history. It may not be necessary to separate the child from the parent, unless the parent is very escalated or if it is apparent the child is receiving information from the parent that may be traumatizing.

Early Verbal to School-Age Children

Although it is very difficult in a busy ED to separate parents from children, talking to a parent in front of a child or vice versa is not best practice. Parents may expose children to information they are not prepared to hear or influence the child’s history with their own emotional response. Children may be fearful of disclosing details (or at all) if the parent is present. The best possible scenario is to speak to the parent separately after they raise a concern of sexual abuse. The child also can be spoken to privately if it is done in a sensitive, developmentally appropriate manner.

It is important to recognize that children have different terminology for private parts. During prior adult questioning, this information will assist in the discussion. The ED clinician should try to obtain as little information as is needed to determine what happened to a child rather than trying to delve deep into the details.

The clinician should note in the record that the child was spoken to outside the presence of the parent and in the presence of a non-relative chaperone, such as a nurse, scribe, technician, or a child life specialist.

The conversation should begin with brief, rapport-building questions, such as asking the child’s birthday, or if there was a recent holiday. Questions about school or pets is another way of building rapport. Let the child know that you are a medical professional. (For example, “I am doctor, and I am here to help you and make sure you are OK.”)

Open-ended questions are the most forensically sound way to obtain information from a child. Open-ended questions require narrative responses. “Can you tell me why you came to the hospital today?” Some young children will stop responding. It is important not to force or push a child to say something or imply that the clinician knows the child has told someone else something. Leading questions are to be avoided. This type of question implies the answer to the question within the question and only requires yes or no answers. (For example, “Did someone touch your privates?”) Additionally, avoid questions such as, “Your mom told me you told her that your uncle touched your privates. Is that right?”

It is far better to stop questioning the child and move on rather than to try to get answers. If a child begins to disclose in more spontaneous and narrative manner, the best responses are “And then what happened?” or “What happened next?” Asking a child how it felt, rather than “Did it hurt?” is more appropriate. Documentation of the questions and answers should be detailed and documented in the child’s own words. A 4-year-old will not say, “I was digitally penetrated by his fingers,” but rather something more akin to, “He touched my private with his hand.”

The examiner already may have determined what the child is referring to as the parts of their body, including genitals. If the examiner is unsure about the child’s terminology, the next question can be “Where is your private (or whatever term they use)?” or “Can you point to that part of your body?” It also is appropriate to ask a child if they are afraid of someone, or, depending on their age, if they feel safe at home.

It is important to thank the child for speaking, even if there is no specific disclosure. The lack of disclosure should not be considered significant. The child may not be ready or willing to talk. Further interviewing will take place in most United States jurisdictions by skilled professionals called forensic interviewers or by someone specially trained by law enforcement or CPS in the appropriate principles of forensic interviewing.

Adolescents

Adolescents present special challenges in history taking. It is the exception that an adolescent should have history taken in front of a parent or caregiver. A careful explanation to the parent or caregiver that the adolescent should have an opportunity to speak to the clinician alone (with a chaperone) can facilitate the process. A parent or caregiver who refuses to allow an adolescent to speak privately raises concerns.

The clinician should not only try to be aware of the reasons that brought the adolescent to the ED but other issues as well, namely substance abuse, sexually transmitted infection (STI) and pregnancy concerns, suicidality and mental health concerns, and other health issues.

Adolescents should be provided with the rules of disclosure to the clinician prior to asking sensitive questions. Trust can be established only if the adolescent understands what can and cannot be disclosed to the authorities and to their parents. Adolescents may protect a sexual partner whom they perceive is a romantic partner, even if the sexual encounter is voluntary but outside of statutory limits.

Consensual activity between age appropriate peers does not have to be disclosed to parents, in most states, if the child is at least 14 years of age and the partner is within a certain age range.

However, this varies from state to state. This consent also extends to testing for STIs, pregnancy, and requests for contraception. Permission for abortion varies depending on the state or territory, and ED clinicians should be guided by their own legal statutes.

Clinicians should know the legal age of consent, the age range between partners where consent can be given, and the age below which no consent can be given for sexual contact. However, reporting to statutory authorities still can be done if these issues are unknown.

As with younger children, non-leading and open-ended questions should be used. A narrative response is optimal, with promptings to say, “And then what happened?” Adolescents can reliably discuss how they feel, if they are afraid, or if they feel safe at home.

Physical Examination: “Normal to be Normal”

More than 30 years of research have demonstrated that the most common findings in child sexual abuse are normal findings. The concept of “it’s normal to be normal” was coined in the early 1990s by Joyce Adams.5-8 Subsequent studies using case control methods and clinical studies have demonstrated repeatedly that more than 95% of prepubertal girls examined non-acutely will have no traumatic findings to the genital area.9-12

When anal findings are studied, which includes both males and females, more than 99% of children will have normal findings.9 Adolescents present a somewhat different picture and are not as well studied, but both acute and chronic findings in adolescents are rare.

Even in sexually active teens, it is unusual to find specific findings resulting from sexual activity. Pregnant adolescents can have normal hymenal anatomy even after giving birth.13

Why are exams normal? In children, the nature of sexual abuse may be progressive, gentle, and not intended by a perpetrator to harm or hurt a child. Injuries and pain suffered by the child usually lead to discovery of an assault. Grooming a child with acts that are intended to seem innocent leading up to possible genital contact and penetrative sex acts may not leave traumatic evidence.

When there is injury, studies have demonstrated that rapid healing of the anogenital area occurs. If a child does not quickly disclose the abuse and subsequently is examined, the injuries often will have healed without any visible sequelae. Studies that look at how genital injuries heal over time often demonstrate that acute trauma can heal completely.

Also, residual injuries may appear normal to the examiner because a child was never examined prior to the sexual contact.14,15

Examination Technique Based on Age and Assent

The General Examination

All children and adolescents presenting for allegations of sexual abuse should have full physical examinations. Exams should preserve modesty in all age groups. A holistic approach assesses for overall growth, development, underlying medical conditions, and evidence of physical abuse or self-harm. No form of child maltreatment exists in isolation. Evidence of physical abuse, neglect, and psychiatric conditions are important in the context of evaluating a child for sexual abuse.

The Genital Examination

Prepubertal. Most prepubertal children can be examined in the ED or clinic without the need for sedation. A careful explanation of the purpose of the examination to the child and parent is essential. The most important reason for an examination to be done in the ED is to exclude acute trauma or injury to the anogenital area. Collection of forensics in prepubertal children is highly specialized and should be done by someone with experience or via referral to a center with experienced professionals.16

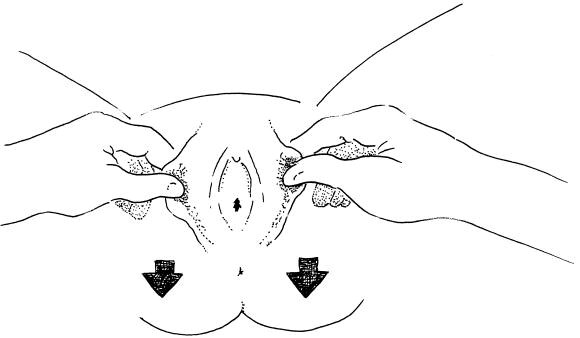

The most common approach is to place the child in the supine frog leg position with draping to preserve modesty. A figure demonstrating positions and techniques for examining prepubertal girls can be found in Figure 1. Examination of the labia majora should occur first. Then, clinicians should use careful traction techniques that allow exposure of the structures of the vestibule to be seen.

Figure 1. Positions and Motions of a Genital Exam for Prepubertal Girls |

|

Reprinted with permission from Girardet RG, Lahoti S, Parks D, McNeese M. Issues in pediatric sexual abuse — What we think we know and where we need to go. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care 2002;32:216-246 and Bernard D, Peters M, Makoroff K. The evaluation of suspected pediatric sexual abuse. Clin Pediatr Emerg Med 2006;7:161-169. |

The hymen has many variations and nearly always opens up with the appropriate application of labial traction. The size of the vaginal opening has no relevance to whether there was injury to the hymen, nor do symmetry, tags, or other structures. The only important issue is whether there is sufficient hymen in the proper locations. The determination of whether sexual abuse has occurred in the nonacute setting without injury should be left to specialists who will use noninvasive magnification techniques, such as colposcopy, to determine if the structures are normal or the findings result from chronic injury.

Acute injury to the anogenital area is more straightforward on physical examination. Bruising, lacerations, abrasions, and bleeding may be present on any part of the anogenital anatomy. There is a differential diagnosis of these conditions that should be considered prior to suggesting there is acute trauma from a sexual assault.

Table 1 lists potential conditions that can cause bleeding. Table 2 lists possible blistering conditions and conditions that cause bruising to the genital area.

Table 1. Differential of Vaginal Bleeding |

Trauma

|

Endocrine

|

Precocious puberty

|

Bleeding disorder

|

Tumor

|

Foreign body |

Infections that can cause bleeding

|

Table 2. Blistering Lesions |

Viral

|

Bacterial

|

Contact dermatitis

|

Clinicians experienced in the evaluation of sexual abuse should be consulted to assist with this assessment. Most injuries to the anogenital area of children heal rapidly. The expectation that acute injuries are still present more than a week past an alleged assault should be considered and reviewed with an expert in the area of sexual abuse of children. If a specialist is not present, photo documentation with the ability to review the images concurrently or in a delayed approach can be very helpful. Telemedicine applications, both synchronous and asynchronous, are available both within and outside of electronic medical records.

The use of expertise in the evaluation of child sexual abuse is critical. Many children’s hospitals will have child abuse pediatricians and child protection teams that are highly trained and experienced in the evaluation of all aspects of child and adolescent sexual abuse and assault. Sexual assault nurse examiners (SANEs) also can provide assistance to the ED, document injuries, and collect evidence. However, as nurses, they may not be able to provide a diagnosis. SANE teams, in an ideal setting, are supervised by experienced physicians. Less experienced examiners, both physicians and nurses, tend to over-call findings.17

Inaccurate assessment of a genital or anal finding may result in unwarranted legal interventions because of misinformation provided by inexperienced examiners.

Adolescent. In the adolescent patient, the examination is very specialized and should be performed by someone with expertise. It may be necessary in the setting of an acute sexual assault, pain, or bleeding to determine whether there is an injury to the anogenital area. Male victims are more straightforward but still require a specialized, compassionate approach that preserves modesty and dignity. An adolescent who presents with a historical or distant complaint of sexual assault does not generally require a forensic assessment or examination.

The examination for evidence of an old injury should be deferred to an experienced professional. However, offering medical care in the form of pregnancy testing and STI testing from blood and urine is appropriate. The concept of checking for virginity is outdated, and statements about a child or adolescent’s virginity should be avoided.

Adolescents need respect for their autonomy to make decisions about their health and can consent to reproductive healthcare issues (in most states) at 14 years of age. This includes not only consenting to examination, collection of physical evidence, and laboratory assessment for STIs, but assessment for suicidality and mental health issues.

Collecting Forensic Evidence

The collection of forensic evidence varies between prepubertal children and adolescents. Peripubertal patients with some evidence of estrogenization require careful thought as to the approach. In many larger centers, sexual assault teams can be nurses, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, or specialized physicians who are called upon to collect forensic evidence. The details of forensic collection are beyond the scope of this review, and each state and center may have different approaches for who performs the collection and where this collection may take place. However, most children will have no physical evidence on or in their bodies after 24 hours or more of an assault.18

Additionally, a consideration of whether a child has been in a situation where they have not bathed or changed clothing should be done. Because most evidence is found on clothing or evidence from the scene, such as bed sheets, hose items may need to be collected by law enforcement. Children who do not have obvious penetrating injury generally only require swabs from external surfaces and oral and anal areas.

Some states have sexual assault evidence collection kits designed for children, and other states may have instructions in the state forms that accompany a generic sexual assault evidence collection kit. Children should not be subjected to internal examination or swabbing of internal structures like the vagina unless there is an indication for an examination under anesthesia.

Adolescent Sexual Assault

Adolescent sexual assault is more likely to involve penetration. Similar to adult sexual assault, it often can involve violence, drugs, or even acquaintance rape. Adolescents also can have consensual sexual relationships that may confound the issue of nonconsensual events.

It is never appropriate for medical providers to judge what may or may not have happened to the adolescent. Instead, provide medical care and forensic assessment based on the adolescent’s presenting history. Other agencies, such as law enforcement, are responsible for investigation and criminal charging.

The timeframe for collecting forensic evidence has changed for adolescents because of advances in deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and body fluid assessment technology. Most states and territories have extended the forensic collection period to up to 96 hours or even a week after sexual contact. Emergency medicine providers should be aware of the timeframes for collection of forensic evidence in their state or jurisdiction because they can vary.

Special Considerations for Sedation or Examination Under Anesthesia

There is a considerable amount of anxiety on the part of patients, providers, and parents when genital examinations are performed secondary to a concern of sexual abuse or assault. This may be true whether the sexual assault occurred in the previous few days or the distant past.

ED providers often think that the examination would be better tolerated (by everyone) if the child receives conscious sedation or is taken to the operating room or sedation unit for a full examination under anesthesia. The reality is that most children and their parents can be reassured that the examination in the ED is only external, not invasive, and for the purpose of determining next steps.

Examinations in children who have no symptoms of pain or bleeding or in whom there is no support for evidence collection can have their examinations deferred to a specialized clinic or children’s advocacy center (CAC) without the loss of evidence. However, reporting the child to appropriate authorities will facilitate a referral to a CAC or clinic where the medical providers are experienced in this type of evaluation.

Sedation should be reserved for situations of medical necessity. Identifying injuries or sources of bleeding in a child who cannot cooperate is one of those situations. Concern for a vaginal or anal foreign body that cannot be removed from an awake child is another indication. To perform sedation in a child without medical need, just for purposes of “seeing if he/she is OK,” should be discouraged.

Sedated exams are very unusual in adolescents unless there is a developmental disability or suspected severe injury with pain and bleeding.

Preparation of the child or adolescent for any examination is critical. A special issue is considered with adolescents who are intoxicated or unconscious and cannot assent to an examination.

The general approach is to wait until the patient is no longer incapacitated and then obtain consent. This includes violent assaults that leave the child or adolescent with a poor prognosis for waking or even may die as a result of injuries. An ethics discussion with the family, the providers, and even statutory authorities may be needed in this unusual and tragic circumstance.

Even children younger than adolescence should provide assent for the examination unless they are injured. No examination should ever be forced on a child. Delaying an examination in a child with a past history of sexual assault and no symptoms or pain or bleeding should not result in any loss of evidence and can be deferred to a specialist clinic or CAC.

Sexually Transmitted Infections

Testing children for STIs has forensic implications and must be done according to Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) standards.19 Although sexually transmitted infections are very rare, even in children who are sexually abused, anxiety and concern by parents and patients about a child acquiring an STI is real.

Children often present with a vulvitis, vaginal discharge, or anal symptoms that raises a concern for STIs. An error in clinical judgment occurs if the examiner only considers STIs as a cause of vulvovaginitis in a prepubertal child.

Other causes of vaginal discharge should be considered because most non-venereal pathogens are more common than STIs as a cause of vaginal discharge in children. Routine culture in addition to appropriate STI testing should be performed in children presenting with a concern of vaginal discharge or vulvoginitis.

Table 3 provides a review of common pathogens that are unrelated to sexual contact and that should be considered when evaluating and treating vaginal discharge in children.

Table 3. Non-Venereal Pathogens in Vaginitis/Vulvitis |

Group A beta hemolytic Streptococcus Streptococcus pneumoniae Staphyloccus aureus/epidermidis/pyogenes Gardnerella vaginalis Haemophilus influenzae Neisseria meningitidis Gram-negative organisms

Fungal

|

If an STI is considered, refer to the standard approaches outlined by the CDC.19 Diagnosis of an STI in childhood raises substantial concerns for sexual contact.

Table 4 is adapted from the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) and CDC for implications of specific STIs in prepubertal children and recommendations for reporting.19

Table 4. Implications of Commonly Encountered Sexually Transmitted or Associated Infections Among Infants and Prepubertal Children for Diagnosis and Reporting of Sexual Abuse |

||

| Infection | Evidence for Sexual Abuse | Recommended Action |

Neisseria gonorrhoeae |

Diagnostic outside the neonatal period |

Report |

Syphilis |

Diagnostic outside the neonatal period |

Report |

Human immunodeficiency virus |

Diagnostic outside the neonatal period or other risk factors (transfusion, etc.) |

Report |

Chlamydia trachomatis |

Diagnostic |

Report |

Trichomonas vaginalis |

Diagnostic |

Report |

Anogenital herpes 1 or 2 |

Suspicious |

Consider report or referral to child abuse specialist |

Condyloma acuminata (anogenital warts) |

Suspicious — if other indicators, sexually transmitted infections, or child older than 5 years of age at first presentation |

Consider report or referral to child abuse specialist |

Anogenital molluscum contagiosum |

Inconclusive |

Medical follow-up |

Bacterial vaginosis or presence of Gardnerella vaginalis |

Inconclusive |

Medical follow-up |

Adapted from Kellogg N; American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Child Abuse and Neglect. The evaluation of child abuse in children. Pediatrics 2005;16:506-512 and Adams JA, Farst KJ, Kellogg ND. Interpretation of medical findings in suspected child abuse: An update for 2018. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2018;31:225-231. |

||

Chlamydia trachomatis/Neisseria gonorrhea/Trichomonas vaginalis

STI tests can be done by Food and Drug Administration-approved nucleic acid amplification tests (NAAT) on dirty urine or a swab of the possible body site. Currently, for Chlamydia trachomatis or Neisseria gonorrhoeae, any positive test by NAAT must be confirmed with second amplification targeting a different portion of the DNA.19

Some centers have this “reflex” or confirmatory testing as part of a standard order set. In children in whom oral or rectal contact is suspected, swabs for Chlamydia trachomatis or Neisseria gonorrhoeae are acceptable as NAATs. Any positive result also should be confirmed for forensic purposes.

There is no equivalent confirmatory test for Trichomonas vaginalis polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing, and the test should be repeated on the urine before treating a patient with a positive result.

Additional serological testing that should be considered includes rapid plasma reagin (syphilis); human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) testing; and tests for hepatitis A, B, and C.

If lesions are present, herpes simplex viruses (HSV) types 1 and 2, should be swabbed for PCR testing. Serological tests for HSV types 1 and 2 are not forensically helpful in the pediatric population.

Any positive test concerning for a sexual transmission should be reviewed with a specialist in child sexual abuse. If possible, it is preferable to hold treatment in children until a consultation can occur, since it will require a discussion about confirmatory testing. STI prophylaxis of prepubertal children is not recommended.

Adolescents

Adolescents are a unique population. The AAP and Society for Adolescent Medicine recommend that all sexually active and at risk adolescents should be tested for STIs.20 There is a variability in how child abuse specialists and forensic nurses approach STIs in the case of sexual assault. One concern is that sexually active individuals who have positive tests taken at the time of an acute assault can cause bias in the investigation of the case. It also may not have forensic value because of the age and ability of a patient to consent to sexual intercourse outside of the assault.

Testing for STIs in the case of sexual assault allows for healthcare and education around those STIs. Confirmatory testing may not be needed in adolescents who are already sexually active. If an STI test is to have forensic value in an adolescent who states the sexual assault was the only sexual activity, then confirmatory testing may be needed.

Triple screens for vaginosis (such as Trichomonas vaginalis, bacterial vaginosis, Candida albicans, and other species) can be used for adolescents presenting with vaginal discharge.

However, the test is not considered “forensic” and may result in false-positive results in prepubertal children.

Prophylaxis of Adolescents Following Sexual Assault

Treatment protocols for HIV post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) and pregnancy are available through the CDC. Standard medication protocols for prophylaxis of STIs are found in publicly available CDC documents.19 Consideration of HIV PEP generally requires consultation with an HIV specialist and clinic for appropriate treatment and follow-up.

Medical Record Documentation

Documentation of the encounter must be done in an accurate and evidence-based manner. Such documentation is critical for follow-up care and further interventions by authorities. Make sure to collect the name of who brought the child in for care and what the relationship to the patient is. Carefully and accurately describe the complaints. Use quotation marks in the record for direct statements from caregivers and, especially, from the child. Document who was present in the room and whether caregivers or parents are separated.

The documentation of the physical examination includes the general examination. Any evidence of genital injury should be documented and photographed. The genital examination should include the Tanner stage of the child, and careful anatomical descriptions are important. For example, erythema of the vulvar area that includes the labia majora should be noted. The labia minora and mucosal structures interior to this constitutes the vestibule. This area includes the urethra, periurethral area, hymen, vagina, posterior fossa, and fourchette.

Terms like “virginity” or “hymen intact” should not be used to describe the examination. If bleeding or discharge is not seen coming directly from the vagina, it is important to use the location (labia minora, perihymenal area) to describe the source of bleeding or discharge. If the anatomy is not clear, the documentation should note this.

Some EDs have the ability to document genital exams by photography for peer review or consultation with a remote specialist. Careful attention to the security of such photos is essential, especially in an electronic medical record.

If the ED physician does not have substantial expertise in the evaluation of sexual abuse, avoid making statements about the interpretation of the examination. Even pediatric emergency medicine physicians may be inaccurate in their determinations.

Parents and authorities may request a definitive answer regarding the child’s physical findings as to whether they support a child’s allegation of sexual abuse. Knowing that more than 95% of prepubertal children examined non-acutely will have normal findings, and many adolescents will have normal findings after sexual activity, caution is required.

Appropriate statements can be, “Your child has no acute injuries today, but I am making a report to Child Protective Services in order for them to have an examination by a specialist in this area.” Such statements provide a more accurate analysis of the issue.

Mandatory Reporting

Follow-up in a specialized clinic or CAC with specially trained providers is critical. Each ED provider should know the resources in their communities for this follow-up. Some centers require that appointments be coordinated with CPS through reporting concerns of abuse. All emergency department providers are mandatory reporters in the United States.

Reporting a concern of child sexual abuse only requires a reasonable suspicion, not proof of the event. ED physicians should err on the side of reporting to CPS for comprehensive assessment and investigations.

Conclusion

Sexual abuse and assault patients often present to the ED. Children and adolescents may both present following an acute assault, but children most commonly present with symptoms that raise a concern of abuse, disclosure of an event that may have occurred sometime in the past, or for general parental concerns.

Many pediatric EDs have specialized teams with experience in the evaluation of child and adolescent sexual abuse. Examination of children and adolescents requires specialized skills and expertise, and the examination always should be done either in consultation with experts or referred out to a center with expertise.

Testing for pregnancy and STIs is an important healthcare intervention, but age and timing since the abuse, as well as symptoms and types of testing, must be considered. Determination of the legal significance of findings should be made with extreme caution and avoided completely if referral to a center with expertise is considered.

The examination always should be performed non-judgmentally, compassionately, and in the best interest of the child in the context of healthcare. Protection from further abuse is critical.

References

- Finkelhor D, Turner H, Colburn D. The prevalence of child sexual abuse with online sexual abuse added. Child Abuse Negl 2024;149:106634.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. National Child Abuse and Neglect Data System (NCANDS) Child File, FFY2022 (2024). NCANDS Child File Codebook Last Reviewed June 30, 2024. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/cb/training-technical-assistance/ncands-child-file-codebook

- Mathews B, Finkelhor D, Pacella R, et al. Child sexual abuse by different classes and types of perpetrator: Prevalence and trends from an Australian national survey. Child Abuse Negl 2024;147:106562.

- Jiang J, Tan Y, Peng C. Sexual orientations in association between childhood maltreatment and depression among undergraduates in mainland of China. J Affect Disord 2023;341:194-201.

- Adams JA. Medical evaluation of suspected child sexual abuse: It’s time for standardized training, referral centers, and routine peer review. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 1999;153:1121-1122.

- Adams JA. Normal studies are essential for objective medical evaluations of children who may have been sexually abused. Acta Paediatr 2003;92:1378-1380.

- Adams JA, Kaplan RA, Starling SP, et al. Guidelines for medical care of children who may have been sexually abused. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2007;20:163-172.

- Adams JA, Harper K, Knudson S, Revilla J. Examination findings in legally confirmed child sexual abuse: It’s normal to be normal. Pediatrics 1994;94:310-317.

- Heger A, Ticson L, Velasquez O, Bernier R. Children referred for possible sexual abuse: Medical findings in 2,384 children. Child Abuse Negl 2002;26:645-659.

- Berenson AB, Chacko MR, Wiemann CM, et al. A case-control study of anatomic changes resulting from sexual abuse. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2000;182:820-831; discussion 831-834.

- Smith TD, Raman SR, Madigan S, et al. Anogenital findings in 3,569 pediatric examinations for sexual abuse/assault. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2018;31:79-83.

- Gallion HR, Milam LJ, Littrell LL. Genital findings in cases of child sexual abuse: Genital vs. vaginal penetration. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2016;29:604-611.

- Kellogg ND, Menard SW, Santos A. Genital anatomy in pregnant adolescents: “Normal” does not mean “nothing happened.” Pediatrics 2004;113:e67-e69.

- McCann J, Miyamoto S, Boyle C, Rogers K. Healing of nonhymenal genital injuries in prepubertal and adolescent girls: A descriptive study. Pediatrics 2007;120:1000-1011.

- McCann J, Miyamoto S, Boyle C, Rogers K. Healing of hymenal injuries in prepubertal and adolescent girls: A descriptive study. Pediatrics 2007;119:e1094-e1106.

- Terrell ME. Identifying the sexually abused child in a medical setting. Health Soc Work 1977;2:112-130.

- Adams JA, Starling SP, Frasier LD, et al. Diagnostic accuracy in child sexual abuse medical evaluation: Role of experience, training, and expert case review. Child Abuse Negl 2012;36:383-392.

- Christian CW, Lavelle JM, De Jong AR, et al. Forensic evidence findings in prepubertal victims of sexual assault. Pediatrics 2000;106:100-104.

- Workowski KA, Bachmann LH, Chan PA, et al. Sexually Transmitted Infections Treatment Guidelines, 2021. MMWR Recomm Rep 2021;70:1-187.

- Committee on Adolescence and Society for Adolescent Health and Medicine; Murray PJ, Braverman PK, Adelman WP. Screening for nonviral sexually transmitted infections in adolescents and young adults. Pediatrics 2014;134:e302-e311.

Child sexual abuse is a common concern for patients presenting to the emergency department. The approach depends not only on the age and development of the child, but also the allegations, time since the contact occurred, and the child's symptoms. It is imperative that all clinicians are familiar with the optimal approach and evaluation of a child with alleged sexual abuse.

Subscribe Now for Access

You have reached your article limit for the month. We hope you found our articles both enjoyable and insightful. For information on new subscriptions, product trials, alternative billing arrangements or group and site discounts please call 800-688-2421. We look forward to having you as a long-term member of the Relias Media community.