Pediatric Hernias: Diagnosis and Management

AUTHORS

Jessica M. Do, MD, MS

Department of Pediatrics, Lucile Salter Packard Children’s Hospital, Stanford School of Medicine, Palo Alto, CA

Mia L. Karamatsu, MD

Assistant Professor of Emergency Medicine and Pediatrics, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA

PEER REVIEWER

Steven M. Winograd, MD, FACEP

Attending Emergency Physician, Trinity Health Care, Samaritan, Troy, NY

Executive Summary

- The incidence of inguinal hernias increases up to 20% to 30% in extremely low-birth-weight (< 1 kg) and pre-term infants and most frequently present in the first year of life.

- Indirect inguinal hernias are caused by the incomplete obliteration and involution of the processus vaginalis. Providers can perform transillumination of the groin or scrotal mass to help differentiate between diagnoses. However, the scrotum can transilluminate in neonates with an inguinal hernia because of the thin intestinal lining.

- Although ultrasound typically is not used to diagnose inguinal hernias, it can be helpful when making a diagnosis. Chen et al found that ultrasound accurately identified 97.9% of hernias vs. 84% when using clinical assessment alone.

- If an incarcerated inguinal hernia is identified, unless the patient is unstable or appears toxic, a reduction should be attempted. Between 70% and 95% of incarcerated inguinal hernias can be reduced successfully at the bedside.

- Umbilical hernias are common in children. They are seen in 10% to 30% of white children in the United States, with a prevalence of up to 85% in African Americans and low-birth-weight infants.

- The differential diagnosis of an umbilical hernia includes an epigastric hernia, hernia of the umbilical cord, omphalocele, abscess, muscle strain, seroma, or hematoma. History and physical examination generally are sufficient for diagnosing umbilical hernias. Imaging is not recommended as the first line. Reassuringly, by 4 to 6 years of age, most umbilical hernias will close spontaneously despite their size. At the time of publication, spontaneous closure was noted to be largely greater than 80%.

- Congenital diaphragmatic hernias (CDHs) typically are the most severe because of the birth defects that result from the hernia. The presence of intestinal viscera within the thoracic cavity leads to abnormal lung development. Therefore, pulmonary hypoplasia and pulmonary hypertension are the most common comorbidities of CDH. Chest radiograph is recommended as the first diagnostic study to confirm the presence of bowel in the thoracic cavity.

- Epigastric hernias, also called ventral hernias, are relatively common in children and have been noted to occur in up to 5% of children.

- A femoral hernia occurs when there is protrusion of the peritoneal sac through the femoral ring. They often are misdiagnosed as inguinal hernias. The provider will palpate the hernia inferior and lateral to the pubic tubercle within the femoral triangle. If uncertain, ultrasound is helpful for making the diagnosis.

Hernias are a common condition encountered by emergency providers and can be overlooked if the genitourinary system isn't included in the evaluation of every child with vomiting or abdominal pain. Incarcerated hernias that are not identified in a timely fashion can have devastating consequences for a child. The authors provide an anatomical review and diagnostic and therapeutic approaches to pediatric hernias.

— Ann M. Dietrich, MD, FAAP, FACEP, Editor

Introduction

Hernias are common in the pediatric population, particularly in infants and young children. Emergency medicine physicians often are tasked with the recognition, diagnosis, and management of pediatric hernias, especially those that require emergent intervention. In children, hernias typically are the result of abdominal wall defects, with inguinal and umbilical hernias being the most common. The less common types include congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH), epigastric hernia, femoral hernia, and other rare types, such as the Spigelian and Amyand’s hernias. Most pediatric hernias are benign and require no urgent interventions; however, it is important to recognize the warning signs and symptoms that indicate an emergency requiring surgical intervention. This article will review the diagnosis and management of pediatric hernias.

Background

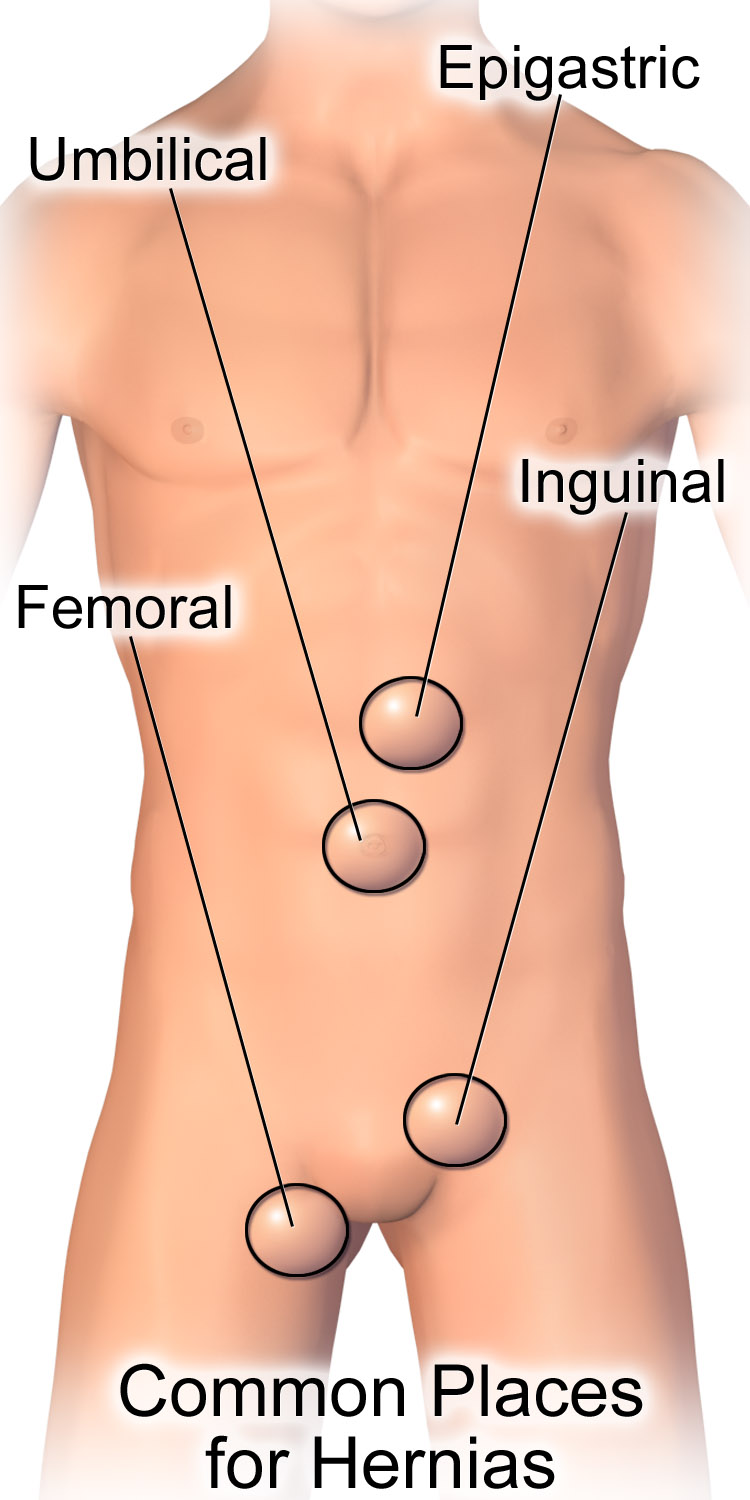

A hernia is defined as “the protrusion of an anatomical structure through the wall that normally contains it.”1 The basic principle of an abdominal hernia formation is that there is an outpouching of viscera through a weakness or defect of the musculature. The bulging can be intermittent or persistent depending on the size of the defect. Increased pressures from crying or straining can cause more prominent bulging. When conducting a history and physical examination, a provider should ask careful questions about the location of the bulge, since it may not be visible or palpable at the time of presentation. Additionally, aspects of the patient’s medical history, such as prematurity or chromosomal abnormality, can be helpful to understand the risk of specific hernia types. Figure 1 shows common hernia locations.

Figure 1. Types of Hernias |

|

Source: BruceBlaus. Hernia common sites. Wikimedia Commons. Published May 23, 2017. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Hernia_Common_Sites. CC BY-SA 4.0. |

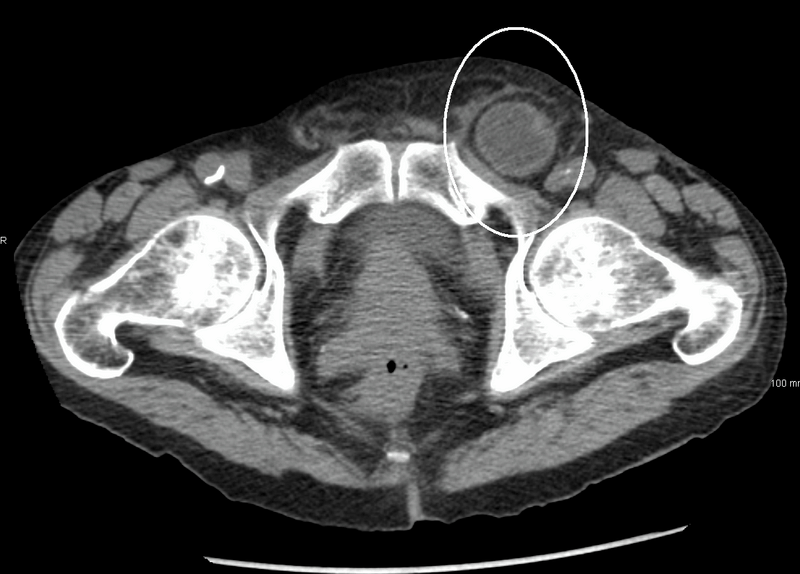

When tissue protrudes through a defect, there is a risk of incarceration and strangulation. Many pediatric hernias are reducible, where the contents can be pushed back through the defect with gentle external pressure. In most cases, the hernia can be reduced, and emergent operative management is not indicated. However, if a hernia cannot be reduced, there is concern for incarceration.2 An incarcerated hernia generally is tender to palpation with possible color change, including erythema. It then can lead to strangulation, where the blood supply to the contents becomes compromised. This process can occur in as little as two hours from the time of incarceration. The ischemic herniated content will not only cause gastrointestinal compromise but also can lead to a systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS). A patient with an incarcerated and strangulated hernia can present to the emergency department with bowel obstruction symptoms, such as abdominal distention, nausea, vomiting, and obstipation. When ischemia is present, the patient may have severe pain. The affected area also can develop a dusky appearance caused by the vascular compromise. It is important to recognize that a patient with a strangulated hernia can present with peritonitis, hematochezia, and shock. See Figure 2 for imaging of an incarcerated hernia.

Figure 2. Incarcerated Hernia on Computed Tomography |

|

Source: Heilman J. Inquinalhernia. Wikimedia Commons. Published June 2, 2011. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Inquinalhernia.png. CC BY-SA 3.0. |

Types of Hernias

Inguinal Hernias

Pediatric inguinal hernias are classified as either indirect or direct. Approximately 0.8% to 5% of term infants develop an inguinal hernia.3,4 The incidence of inguinal hernias increases up to 20% to 30% in extremely low-birth-weight (< 1 kg) and pre-term infants.5,6 Inguinal hernias most frequently present in the first year of life. They occur equally among ethnicities. Indirect inguinal hernias are one of the most common forms of hernias in pediatric patients, with an incidence of about 4% to 10%.7,8 Indirect inguinal hernias more commonly are seen in males than females (6-10:1).4 Girls have a higher incidence of bilateral inguinal hernias (25.4% vs. 12.9%), but they have the same risk for incarceration.3 Congenital direct inguinal hernias are uncommon, occurring in less than 1% of all inguinal hernias.9

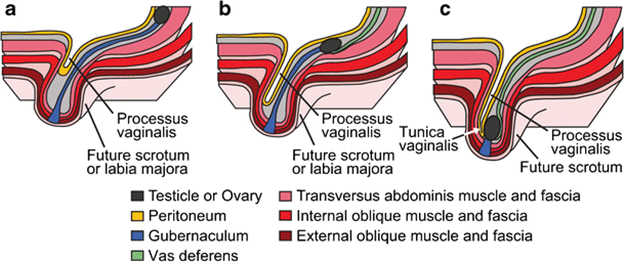

Indirect inguinal hernias are caused by the incomplete obliteration and involution of the processus vaginalis.10 In males between 25 to 35 weeks of gestation, the testes pass through the processus vaginalis, which is an extension of the peritoneal lining.11 The processus vaginalis then elongates down through the inguinal canal as the testes descend into the scrotum. Normally, the processus vaginalis obliterates between 36 and 40 weeks of gestation, forming the tunica vaginalis; however, if it remains patent, it allows communication between the abdomen and scrotum. If the communication is large, it can result in an indirect inguinal hernia; if it is small, it likely will result in a hydrocele.

In females, the extension of the peritoneal lining is called the diverticulum or canal of Nuck, which communicates with and terminates in the labia majora. Like the processus vaginalis, it closes at 36 to 40 weeks of gestation.

The processus vaginalis can remain patent in 60% of infants younger than 12 months of age and 40% of children younger than 24 months of age.12 The descent of the right testicle is preceded by the left, resulting in the earlier involution of the left processus vaginalis. Therefore, it is not surprising that approximately 60% of indirect inguinal hernias are right-sided, 30% are on the left, and 10% are bilateral.11,13 Figure 3 depicts the process of genital development.14

Figure 3. Process of Genital Formation14 |

|

Reprinted with permission from Sameshima YT, Yamanari MGI, Silva MA, et al. The challenging sonographic inguinal canal evaluation in neonates and children: An update of differential diagnoses. Pediatr Radiol 2017;47:461-472. |

Most inguinal hernias are asymptomatic and present with an intermittent bulge in the groin, scrotum, or labia. However, the patient may present with a swelling that does not spontaneously reduce.

Diagnoses to consider for groin and scrotal masses in males include an indirect inguinal hernia, hydrocele, undescended testicle, testicular torsion, varicocele, retractile testis, direct inguinal hernia, femoral hernia, abscess, or lymphadenopathy. The differential diagnosis for females with groin swelling includes abscess, cyst, lymphadenopathy, indirect or direct inguinal hernia, femoral hernia, or herniated ovary with or without an associated fallopian tube. The provider’s history should include questions asking about the location and qualities of the bulge, including color, timing, and tenderness.

Careful examination should be performed for inguinal hernias because of the broad differential. Palpate for bilateral testes within the scrotum, then palpate the internal ring, external ring, and spermatic cord.10 When indirect inguinal hernias become incarcerated, it usually happens at the internal ring. The incarcerated hernia may put pressure on the spermatic cord and eventually lead to testicular infarction. Providers also can perform transillumination of the groin or scrotal mass to help differentiate between diagnoses. However, the scrotum can transilluminate in neonates with an inguinal hernia because of the thin intestinal lining. Thickening of the cord structures or “silk glove sign” indicates a hernia sac.

Although ultrasound typically is not used to diagnose inguinal hernias, it can be helpful when making a diagnosis.15 Chen et al found that ultrasound accurately identified 97.9% of hernias vs. 84% when using clinical assessment alone.16 If the patient has a bowel obstruction, abdominal radiographs can be helpful and may show gas-filled loops of bowel in the scrotum.

Table 1 lists the characteristics of various groin masses in male patients.

Table 1. Physical Characteristics of Groin Masses in Males |

||||

| Groin Mass | Tender | Reducible | Transillumination | Skin Changes |

Inguinal hernia |

Yes, if incarcerated or strangulated |

Yes, if not incarcerated or strangulated |

No, except possibly in neonates |

Maybe if incarcerated or strangulated |

Hydrocele |

No |

No |

Yes |

No |

Undescended testicle |

No |

No |

No |

No |

Groin abscess/cyst |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

Possible erythema |

Femoral hernia |

Yes, if incarcerated or strangulated |

Yes, if not incarcerated or strangulated |

No |

Maybe if incarcerated or strangulated |

If the inguinal hernia spontaneously resolves or reduces easily with gentle pressure, then the patient may be discharged home with a referral for elective repair. There is debate about the timing of the herniorrhaphy because there is a higher rate of incarceration of inguinal hernias in infants. Incarceration of inguinal hernias occurs in 3% to 16% of patients and can occur in up to 31% of infants born prematurely, typically presenting by 12 months of age.5,17 If an incarcerated inguinal hernia is identified, unless the patient is unstable or appears toxic, a reduction should be attempted. Between 70% and 95% of incarcerated inguinal hernias can be reduced successfully at the bedside.17,18

The manual reduction of an incarcerated hernia is accomplished using the taxis maneuver. First, the provider should ensure adequate analgesia and/or sedation with appropriate monitoring, to optimize for success. Ice packs can be used to reduce swelling. The patient then is placed in the Trendelenburg or supine position, and the provider applies slow and firm bimanual pressure to the hernia. The gas and other contents are first “milked out” of the incarcerated bowel, after which steady bimanual pressure is applied to the inguinal canal (over the external ring) and the distal hernia. The pressure is aimed toward the abdominal cavity on the same axis as the inguinal canal until the hernia is completely reduced, which can take up to five minutes. Once reduced, ensure the inguinal canal is empty up to the internal ring. After confirming the hernia is completely reduced, the patient can be discharged home with strict return precautions.

There is a high risk for recurrent incarceration. One study found that 52.9% of 153 patients with incarcerated hernias had a previous episode of incarceration.19 Therefore, the provider must make a referral to a pediatric surgeon for urgent herniorrhaphy for repair within five to seven days.20,21 If the hernia is not successfully reduced or there are signs of strangulation, emergent consultation to pediatric surgery is warranted.

Hernia repair is recommended for all inguinal hernias, making it one of the most common surgical procedures in pediatric patients.22 There are many instances where bilateral hernias are present when an inguinal hernia is first diagnosed and repaired. Inguinal hernias present with an increased risk of a contralateral metachronous hernia formation, with an incidence of 5.6% to 31%, and is highest in children younger than 2 years old or pre-term infants.23,24 A recent retrospective study found a 3.8% risk of contralateral hernia development by 10 years of age.25 There is debate over current surgical management regarding routine contralateral exploration, unilateral vs. bilateral repair, and laparoscopic vs. the traditional high open ligation. For more information, please refer to the updated American Academy of Pediatrics clinical report on pediatric inguinal hernias published in July 2023.26 Recurrence of hernia after an elective repair is ~1%, but it can be up to 24% in patients with certain risk factors, such as incarceration, ascites, and ventriculoperitoneal shunt.

Umbilical Hernias

Umbilical hernias are common in children. They are seen in 10% to 30% of white children in the United States, with a prevalence of up to 85% in African Americans and low-birth-weight infants.27,28 The incidence of umbilical hernias also is affected by birth weight and certain syndromes, such as Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome, Trisomy 18 or 21, or Marfan syndrome.8

Umbilical hernias are formed from a small abdominal wall defect, which is where the umbilical vessels pass during gestation.13 The umbilical ring should close within the first few weeks of infancy, but persistence of the defect can cause the hernia to form. Umbilical hernias are visualized at the umbilicus as a bulge. The differential diagnosis includes an epigastric hernia (discussed later), hernia of the umbilical cord, omphalocele, abscess, muscle strain, seroma, or hematoma. History and physical examination generally are sufficient for diagnosing umbilical hernias. Imaging is not recommended as the first line. Reassuringly, by 4 to 6 years of age, most umbilical hernias will close spontaneously despite their size.29 At the time of publication, spontaneous closure was noted to be largely greater than 80%.

An umbilical hernia largely is a benign condition that requires no emergent consultation. Fortunately, incarceration of umbilical hernias is considered uncommon. However, a retrospective review of 489 patients who underwent umbilical hernia repair noted 7% of patients required repair because of complications, which included incarceration in 22 patients.27 The incidence of strangulation is less than 1% of cases.27 Patients can be followed by their pediatrician with pediatric surgery consultation as an outpatient. Surgery usually is not recommended until after 4 to 6 years of age or if the defect is larger than 1.5 cm to 2 cm.30,31

Parents can be instructed to monitor the hernia for signs indicative of incarceration or strangulation, including color change or tenderness. However, the provider should reassure the family, given that the risk of either is quite low. It must be noted that there are no clear guidelines that dictate when surgical closure is appropriate. A meta-analysis showed that most institutions will proceed with closure around 4 to 5 years of age regardless of the size of the defect.32 However, if there are concerns of strangulation or incarceration, like the other hernias, pediatric surgery should be consulted for emergent management.

Diaphragmatic Hernias

Congenital diaphragmatic hernias (CDHs) occur in 1 of every 3,000 live births, according to one literature review.33 CDH typically is diagnosed antenatally or soon after birth. However, 5% to 25% are diagnosed outside of the neonatal period.34 Most cases occur sporadically, but there have been rare inheritance patterns reported. CDH is considered isolated in 50% to 70% of cases. However, 30% to 50% of cases are complex and associated with chromosomal defects or syndromes.35

Early in development, the pleuroperitoneal folds fuse with the septum transversum and other nearby mesentery and musculature forming the muscular part of the diaphragm.36 The left side closes about one week after the right. CDH forms from incomplete fusion of any of these parts. There are several types of diaphragmatic hernias, but the most common involves the posterolateral wall. This type of CDH is termed the Bochdalek hernia. It occurs on the left side in 80% to 85% of cases. However, a right-sided defect is seen in 10% to 15% of cases, and bilateral defects are in 1% to 2% of cases. Because of the defect, the intestines and even the stomach (particularly on the left side) enter the thoracic cavity.

Identification of CDH most often is made through prenatal routine anatomy ultrasound scans.37 These scans typically occur between 22 to 24 weeks of gestation, where routine prenatal care occurs. If the CDH is very large, it may be seen in first trimester scans. However, it also can be diagnosed postnatally when the infant develops severe respiratory distress. A rare subgroup is the late-presenting CDH, which does not present until after the neonatal period. The patient may present with acute or insidious respiratory or gastrointestinal symptoms. Late-presenting CDHs are thought to have a better prognosis.38

Of the hernias discussed in this article, CDHs typically are the most severe because of the deficits that result from the hernia.39 The presence of intestinal viscera within the thoracic cavity leads to abnormal lung development. Therefore, pulmonary hypoplasia and pulmonary hypertension are the most common comorbidities of CDH. However, many other organ systems may have implications depending on the etiology of the CDH, including cardiovascular, urogenital, musculoskeletal, central nervous, and craniofacial.

Late-presenting CDH can present acutely or have an insidious onset.40 If an infant presents to the emergency department with severe respiratory distress, with or without gastrointestinal symptoms, consider CDH. Furthermore, patients with late-presenting CDH can have a variety of nonspecific respiratory or gastrointestinal symptoms, including cough, dyspnea, tachypnea, abdominal pain, diarrhea, or vomiting. In these patients, a thorough history and physical examination are crucial for an appropriate diagnosis. The differential diagnosis for vague respiratory and gastrointestinal symptoms is vast, so coupling the history with an examination of the lungs is particularly important. Patients with CDH have asymmetric decreased breath sounds and may have bowel sounds in the affected hemithorax.

Chest radiograph (CXR) is recommended as the first diagnostic study to confirm the presence of bowel in the thoracic cavity. Figure 4 shows a CXR indicating a congenital right-sided diaphragmatic hernia in a neonate. Computed tomography (CT) can confirm the diagnosis and further delineate the severity of the CDH. Alternate studies to confirm the diagnosis of CDH include a CXR after the passage of a nasogastric tube or an upper gastrointestinal series. Management of severe CDH often includes immediate intubation, intensive pharmacological treatment, and even extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. If the patient has late-presenting CDH with mild symptoms, emergent surgical consultation still is the appropriate treatment.

Figure 4. Chest Radiograph of a Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia |

|

Kinderradiologie Olgahospital Klinikum Stuttgart. ZwH kl. Wikimedia Commons. Pubilshed Dec. 2, 2014. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:ZwH_kl.jpeg. CC BY-SA 4.0. |

Epigastric Hernias

Epigastric hernias, also called ventral hernias, are relatively common in children and have been noted to occur in up to 5% of children.41 These hernias form when there is a failure of the rectus muscle to approximate at the linea alba at the upper midline.42 About half of patients are symptomatic.43 The bulge is located in the epigastric region, as the name implies. Differential diagnosis includes an umbilical hernia, abscess, muscle strain, seroma, and rectus sheath hematoma. History and physical examination alone typically are sufficient to diagnose an epigastric hernia, and imaging is not indicated as first line.

The hernias often are painless, but patients can report pain with activity or trauma to the area or can exhibit signs of tenderness to palpation. Epigastric hernias are reducible up to 50% of the time, and strangulation of epigastric hernias is rare. Although reports differ, some sources state that epigastric hernias do not spontaneously close but that surgery is warranted if the hernia enlarges or becomes painful. If emergent surgery is not warranted, outpatient consultation to pediatric surgery for primary surgery and discharge with return precautions can be performed. Parents should be counseled that the occurrence of strangulation is a rare complication.

Femoral Hernias

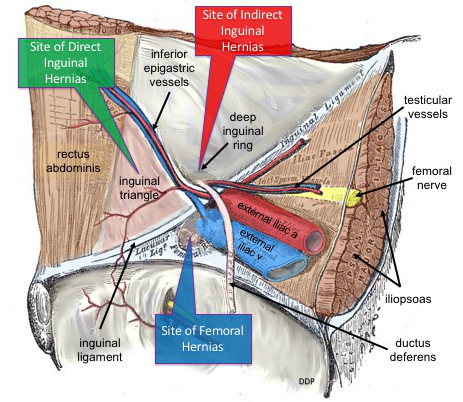

Femoral hernias are rare in pediatrics, especially in infants.44 Regarding groin hernias, they have an incidence of less than 1%.13,45 A femoral hernia occurs when there is protrusion of the peritoneal sac through the femoral ring. The importance of femoral hernias in pediatric patients is that they often are misdiagnosed as inguinal hernias.46 Pediatric femoral hernias are misdiagnosed in 40% to 75% of patients.45,47,48 Like inguinal hernias, they also are more often seen on the right side. Therefore, the differential diagnosis is similar to that of inguinal hernias: hydrocele, undescended testicle, testicular torsion, abscess, lymphadenopathy, or herniated ovary with or without an associated fallopian tube. Because of their misdiagnosis, femoral hernias often are managed operatively as such. If a patient presents to the emergency department with recurrence of groin swelling after surgical management of inguinal hernias, one must consider a femoral hernia.

The provider will palpate the hernia inferior and lateral to the pubic tubercle within the femoral triangle. This is not the same location where inguinal hernias are palpated. Figure 5 shows the locations of both hernias. Additionally, femoral hernias are not manipulated by digital occlusion of the inguinal ring like inguinal hernias are. The workup of femoral hernias primarily is clinical without use of ultrasound or laboratory work. However, if findings are ambiguous, ultrasound can be performed to help determine the diagnosis. If there is recurrence of a hernia after surgical intervention, consult pediatric surgery for possible laparoscopy to evaluate.

Figure 5. Sites of Inguinal and Femoral Hernias |

|

DePace DM. Common sites of lower abdominal hernias. Wikimedia Commons. Published March 30, 2019. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Common_Sites_of_Lower_Abdominal_Hernias.jpg. CC BY-SA 4.0. |

Given the high incidence of strangulation, upon diagnosis of a femoral hernia, the provider should place an outpatient referral to pediatric surgery if possible and discuss follow-up and signs and symptoms of incarceration and strangulation with the caregiver.

Spigelian Hernia

A Spigelian hernia is a rare abdominal hernia, especially in children. It is caused by a congenital or acquired defect. In children, these hernias usually are caused by trauma or associated with other anomalies. They also can be associated with ipsilateral cryptorchidism.49,50 Urgent repair is recommended because they have a high rate of incarceration and strangulation.

Amyand’s Hernia

Amyand’s hernia occurs when the appendix is trapped in an inguinal hernia.51 The appendix can become inflamed, incarcerated, and strangulated.52 It is three times more likely to be diagnosed in a child than an adult.53 The diagnosis is difficult preoperatively and typically is discovered during surgery.

Summary

Hernia diagnosis and management is an important topic in pediatric emergency medicine. Many hernias are benign, but hernias such as congenital diaphragmatic hernias, in addition to the hernia complications, should be taken seriously.

As a rule of thumb, most asymptomatic pediatric hernias do not require emergent intervention. Many hernias are diagnosed clinically without the need for further workup, including an ultrasound. If a hernia appears to be incarcerated, manual maneuvers to reduce the hernia can be performed in the emergency department with adequate sedation. In addition, pediatric surgery should be consulted, since urgent surgical intervention is required. Strangulated hernias require emergency surgery, and preparation for the operating room, in addition to management of the patients’ symptoms, is necessary. Undiagnosed incarceration can lead to the necrosis of bowel and cause unintended gastrointestinal complications. Furthermore, the necrotic tissue can eventually cause a SIRS response and shock. Patients with CDHs are at high risk for cardiorespiratory compromise, and immediate intervention to stabilize these systems should be performed.

References

- Venes D. Taber's Cyclopedic Medical Dictionary. 24th ed. F.A. Davis Company; 2021.

- Pastorino A, Alshuqayfi AA. Strangulated hernia. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

- Chang S-J, Chen J Y-C, Hsu C-K, et al. The incidence of inguinal hernia and associated risk factors of incarceration in pediatric inguinal hernia: A nation-wide longitudinal population-based study. Hernia 2016;20:559-563.

- Grosfeld JL. Current concepts in inguinal hernia in infants and children. World J Surg 1989;13:506-515.

- Rajput A, Gauderer MW, Hack M. Inguinal hernias in very low birth weight infants: Incidence and timing of repair. J Pediatr Surg 1992;27:1322-1324.

- Kumar VH, Clive J, Rosenkrantz TS, et al. Inguinal hernia in preterm infants (< or = 32-week gestation). Pediatr Surg Int 2002;18:147-152.

- Pogorelić Z, Rikalo M, Jukić M, et al. Modified Marcy repair for indirect inguinal hernia in children: A 24-year single center experience of 6,826 pediatric patients. Surg Today 2017;47:108-113.

- Kelly KB, Ponsky TA. Pediatric abdominal wall defects. Surg Clin North Am 2013;93:1255-1267.

- Abdulhai SA, Glenn IC, Ponsky TA. Incarcerated pediatric hernias. Surg Clin North Am 2017;97:129-145.

- Yeap E, Pacilli M, Nataraja RM. Inguinal hernias in children. Aust J Gen Pract 2020;49:38-43.

- Graf JL, Caty MG, Martin DJ, Glick PL. Pediatric hernias. Semin Ultrasound CT MR 2002;23:197-200.

- Saad S, Mansson J, Saad A, Goldfarb MA. Ten-year review of groin laparoscopy in 1,001 pediatric patients with clinical unilateral inguinal hernia: An improved technique with transhernia multiple-channel scope. J Pediatr Surg 2011;46:1011-1014.

- Brandt ML. Pediatric hernias. Surg Clin North Am 2008;88:27-43, vii-viii.

- Sameshima YT, Yamanari MGI, Silva MA, et al. The challenging sonographic inguinal canal evaluation in neonates and children: An update of differential diagnoses. Pediatr Radiol 2017;47:461-472.

- Toms AP, Dixon AK, Murphy JM, Jamieson NV. Illustrated review of new imaging techniques in the diagnosis of abdominal wall hernias. Br J Surg 1999;86:1243-1249.

- Chen KC, Chu CC, Chou TY, Wu CJ. Ultrasonography for inguinal hernias in boys. J Pediatr Surg 1998;33:1784-1787.

- Stylianos S, Jacir NN, Harris BH. Incarceration of inguinal hernia in infants prior to elective repair. J Pediatr Surg 1993;28:582-583.

- Lau ST, Lee YH, Caty MG. Current management of hernias and hydroceles. Semin Pediatr Surg 2007;16:50-57.

- Niedzielski J, Kr l R, Gawłowska A. Could incarceration of inguinal hernia in children be prevented? Med Sci Monit 2003;9:CR16-18.

- Stephens BJ, Rice WT, Koucky CJ, Gruenberg JC. Optimal timing of elective indirect inguinal hernia repair in healthy children: Clinical considerations for improved outcome. World J Surg 1992;16:952-956; discussion 957.

- Gahukamble DB, Khamage AS. Early vs. delayed repair of reduced incarcerated inguinal hernias in the pediatric population. J Pediatr Surg 1996;31:1218-1220.

- Esposito C, Escolino M, Turrà F, et al. Current concepts in the management of inguinal hernia and hydrocele in pediatric patients in laparoscopic era. Semin Pediatr Surg 2016;25:232-240.

- Burgmeier C, Dreyhaupt J, Schier F. Comparison of inguinal hernia and asymptomatic patent processus vaginalis in term and preterm infants. J Pediatr Surg 2014;49:1416-1418.

- Nataraja RM, Mahomed AA. Systematic review for paediatric metachronous contralateral inguinal hernia: A decreasing concern. Pediatr Surg Int 2011;27:953-961.

- Clark JJ, Limm W, Wong LL. What is the likelihood of requiring contralateral inguinal hernia repair after unilateral repair? Am J Surg 2011;202:754-757; discussion 757-758.

- Khan FA, Jancelewicz T, Kieran K, et al; AAP Committee on Fetus and Newborn, Section on Surgery, Section on Urology. Assessment and management of inguinal hernias in children. Pediatrics 2023;152:e2023062510.

- Zendejas B, Kuchena A, Onkendi EO, et al. Fifty-three-year experience with pediatric umbilical hernia repairs. J Pediatr Surg 2011;46:2151-2156.

- Cilley R. Disorders of the umbilicus. In: Grosfeld JL, O’Neill J, Coran A, et al, eds. Pediatric Surgery. Elsevier;2006:1143-1156.

- Troullioud Lucas AG, Jaafar S, Mendez MD. Pediatric umbilical hernia. In: StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2023.

- Gill FT. Umbilical hernia, inguinal hernias, and hydroceles in children: Diagnostic clues for optimal patient management. J Pediatr Health Care 1998;12:231-235.

- Almeflh W, AlRaymoony A, AlDaaja MM, et al. A systematic review of current consensus on timing of operative repair vs. spontaneous closure for asymptomatic umbilical hernias in pediatric. Med Arch 2019;73:268-271.

- Zens T, Nichol PF, Cartmill R, Kohler JE. Management of asymptomatic pediatric umbilical hernias: A systematic review. J Pediatr Surg 2017;52:1723-1731.

- Comberiati P, Giacomello L, Camoglio FS, Peroni DG. Diaphragmatic hernia in a pediatric emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care 2015;31:354-356.

- Cigdem MK, Onen A, Okur H, Otcu S. Associated malformations in Morgagni hernia. Pediatr Surg Int 2007;23:1101-1103.

- Chatterjee D, Ing RJ, Gien J. Update on congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Anesth Analg 2020;131:808-821.

- Zani A, Chung WK, Deprest J, et al. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2022;8:37.

- Tovar JA. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2012;7:1.

- Ghabisha S, Ahmed F, Al-Wageeh S, et al. Delayed presentation of congenital diaphragmatic hernia: A case report. Pan Afr Med J 2021;40:242.

- Kosiński P, Wielgoś M. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia: Pathogenesis, prenatal diagnosis and management — literature review. Ginekol Pol 2017;88:24-30.

- Kitano Y, Lally KP, Lally PA; Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia Study Group. Late-presenting congenital diaphragmatic hernia. J Pediatr Surg 2005;40:1839-1843.

- Kokoska E, Weber T. Umbilical and supraumbilical disease. In: Ziegler M, Azizkhan R, Weber T, eds. Operative Pediatric Surgery. McGraw-Hill;2003:543-554.

- Tinawi GK, Stringer MD. Epigastric hernias in children: A personal series and systematic review of the literature. Eur J Pediatr Surg 2022;32:139-145.

- Coats RD, Helikson MA, Burd RS. Presentation and management of epigastric hernias in children. J Pediatr Surg 2000;35:1754-1756.

- Aneiros Castro B, Cano Novillo I, García Vázquez A, et al. Pediatric femoral hernia in the laparoscopic era. Asian J Endosc Surg 2018;11:233-237.

- Radcliffe G, Stringer MD. Reappraisal of femoral hernia in children. Br J Surg 1997;84:58-60.

- Haggui B, Hidouri S, Ksia A, et al. Femoral hernia in children: How to avoid misdiagnosis? Afr J Paediatr Surg 2021;18:164-167.

- De Caluwé D, Chertin B, Puri P. Childhood femoral hernia: A commonly misdiagnosed condition. Pediatr Surg Int 2003;19:608-609.

- Al-Shanafey S, Giacomantonio M. Femoral hernia in children. J Pediatr Surg 1999;34:1104-1106.

- Sengar M, Mohta A, Neogi S, et al. Spigelian hernia in children: Low vs. classical. J Pediatr Surg 2018;53:2346-2348.

- Patoulias I, Rahmani E, Patoulias D. Congenital Spigelian hernia and ipsilateral cryptorchidism: A new syndrome? Folia Med Cracov 2019;59:71-78.

- Murugan S, Grenn EE, Morris MW Jr. Left-sided Amyand hernia. Am Surg 2022;88:1561-1562.

- Ivanschuk G, Cesmebasi A, Sorenson EP, et al. Amyand's hernia: A review. Med Sci Monit 2014;20:140-146.

- Baldassarre E, Centonze A, Mazzei A, Rubino R. Amyand's hernia in premature twins. Hernia 2009;13:229-230.

Hernias are a common condition encountered by emergency providers and can be overlooked if the genitourinary system is not included in the evaluation of every child with vomiting or abdominal pain. Incarcerated hernias that are not identified in a timely fashion can have devastating consequences for a child. The authors provide an anatomical review, along with diagnostic and therapeutic approaches to pediatric hernias.

Subscribe Now for Access

You have reached your article limit for the month. We hope you found our articles both enjoyable and insightful. For information on new subscriptions, product trials, alternative billing arrangements or group and site discounts please call 800-688-2421. We look forward to having you as a long-term member of the Relias Media community.