Pain Control in Older Adults

May 1, 2024

Related Articles

-

Infectious Disease Updates

-

Noninferiority of Seven vs. 14 Days of Antibiotic Therapy for Bloodstream Infections

-

Parvovirus and Increasing Danger in Pregnancy and Sickle Cell Disease

-

Oseltamivir for Adults Hospitalized with Influenza: Earlier Is Better

-

Usefulness of Pyuria to Diagnose UTI in Children

AUTHORS

Brittany Denny, MD, Emergency Medicine PGY-3, Chief Resident, Wright State University, Dayton, OH

Titus Chu, MD, Assistant Professor, Emergency Medicine, Wright State University, Dayton, OH

PEER REVIEWER

Dennis Hanlon, MD, FAAEM, Vice Chairman, Academics, Department of Emergency Medicine, Allegheny General Hospital, Pittsburgh, PA

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

- A misconception held by patients, caregivers, and medical professionals that contributes to the underrecognition and undertreatment of pain is the idea that pain is a normal part of the aging process.

- Depression can affect individuals of any age, but older adult populations have been found to have a higher prevalence of comorbid pain and depression, affecting up to 13% of the older adult population, with pain increasing the risk of depression up to fourfold.

- The most well-validated pain assessment is self-reporting of pain, but this method leads to dramatic underdetection and undertreatment of pain in patients with cognitive impairment.

- Given challenges associated with aging, such as physiologic changes and comorbidities, multimodal pain management of both pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic interventions must be considered to balance between pain management and side effects.

- Nonpharmacologic treatment should be considered first line in conjunction with analgesic medications. These nonpharmacologic treatment modalities include heat or ice, massage therapy, physiotherapy, nutritional supplements, and alternative therapies.

— Ann M. Dietrich, MD, Editor

Introduction

Pain is defined as an unpleasant sensory or emotional experience associated with potential tissue damage or actual tissue damage.1,2 Pain is one of the most common reasons adults seek medical care.3 When surveyed, older adults consider pain one of their greatest health inconveniences.4 In older adults, pain is highly common, costly, and frequently disabling.5 As the aging population increases, providers are more likely to be required to manage pain in older adult patients.6

Pain is a highly subjective experience of noxious stimuli, and this subjectivity makes the treatment of pain difficult.7 Pain control in older adults is notoriously difficult because of factors related to aging, such as comorbid conditions, polypharmacy and potential pharmacological interactions, difficulty in pain assessment due to cognitive impairments, and physiologic changes in older adult patients.1,2 There are limited guidelines regarding pain management in older adults despite a high prevalence of painful conditions in this population.8

A misconception held by patients, caregivers, and medical professionals that contributes to the underrecognition and undertreatment of pain is the idea that pain is a normal part of the aging process.5,8,9 The belief that pain is a part of aging can cause pain to go entirely undetected.10 Additionally, providers’ lack of trust in patient reporting of pain combined with fear of causing harm are barriers to assessment and treatment of pain.5 With an aging population, society cannot continue the idea that pain is a normal experience of aging.4

Appropriate pain management not only is a fundamental human right, but it benefits the healthcare system as a whole.11,12 Effective pain management leads to decreased morbidity and mortality, faster recovery, and shorter hospital stays, which ultimately leads to decreased healthcare dollars.8 Therefore, it is important to understand the unique aspects regarding pain control in older adults.

Epidemiology and Etiology

Pain affects approximately 20% of American adults.13 The older adult population comprises the fastest growing part of the world’s population.14 The number of people worldwide older than 65 years of age was estimated at 506 million in 2008 and will increase to 1.3 billion by 2040.14 By 2030, all baby boomers will be older than 65 years of age, and the older adult population will outnumber children in the United States.15 The prevalence of chronic pain increases with age and is doubled among older adults compared to younger people, 27.6% in adults aged 65-84 years vs. 13.2% in adults aged 25-44 years.13

The risk of experiencing pain reaches its highest levels in the latest years of life.9 Older adults have higher rates of surgery, chronic disease, and hospitalization that increase the risk of pain.5 With advancing age, older adults experience a variety of comorbidities and chronic conditions that alter pain and the ability to manage it.8,9 These comorbidities complicate evaluation and treatment due to greater potential for adverse effects.9 Peripheral arterial disease, low back pain, high body mass index (BMI), and female sex are associated with a higher risk of pain experienced in older adults.16 This could be due in part to progression of illness but also to avoidance of movement because of fear of pain.17 Hypertension is independently associated with activity-limiting pain, and older patients with hypertension had a higher prevalence of pain symptoms, more anatomical locations with pain, and higher frequency of pain medication use.13

In an Australian study of people older than 70 years of age, 41% of males and 50% of females experienced pain on most days.18 Pain severity was higher for those 80 years of age or older.18 In community dwelling older adults, pain prevalence was 50% of adults, while pain in institutionalized older adults reaches as high as 80%.9,16 Even with these estimates, pain often is underdiagnosed and undertreated in those living with cognitive impairments.9

The aging process predisposes patients to acute and chronic pain conditions, with acute pain related to trauma, surgery, and nontraumatic fractures.5 Common chronic conditions associated with pain in older adults include osteoarthritis, bone and joint disorders, cancer, postherpetic neuralgia, diabetic neuropathy, low back pain including spondylosis and radiculopathies, post-stroke pain, and Parkinson’s disease.6,14

The prevalence of musculoskeletal pain in older adults living in the community ranges from 25% to 43%, with 40% of adults reporting pain in two or more sites.19 Older adults consistently report back, hip, knee, and other joints such as fingers, wrists, and toes as the main sites of pain.6,20 Joint pain reporting was higher in older adult patients with lower levels of education, lower income households, and in fair or poor physical or mental health.21 Low back pain in the older adult population ranged from 21% to 75% of patients and led to functional disability in 60% of the studies.22

Older adult patients are more likely to have multisite pain.14 When thoroughly assessed, pain is experienced at four or more sites in one-fifth of patients 65 years of age and older.6 Multisite pain is associated with significant impairments in physical performance and lower balance confidence.23 Experiencing pain at multiple sites affects physical fitness, emotions, and social activities more than single pain sites; thus, consideration of multisite pain is critical.24 While identifying specific pain sites is important, identifying widespread pain or the number of pain sites may be more important for outcomes of older adults.25

Factors associated with increased rates of pain include increased body mass, lower levels of education, and socioeconomic status.6 A negative correlation was found between education and pain perception.26 There was a higher prevalence of pain among rural residents and in uninsured people.26 Patients with lower monthly incomes had a higher prevalence of pain, and the inability to consistently afford prescribed interventions is thought to play a role.20

BMI was found to be a risk factor for increased mild to severe pain trends.16,27 Lower BMI was significantly associated with lower pain ratings.17 However, frailty is associated with increased risk of pain.5,28 Both pain and frailty are associated with functional decline and have negative effects on quality of life in older adults.28

Depression can affect individuals of any age, but older adult populations have been found to have a higher prevalence of comorbid pain and depression, affecting up to 13% of the older adult population.29 Pain increases the risk of depression up to fourfold.29 Patients with major depressive disorder are three times more likely to experience non-neuropathic pain and six times more likely to experience neuropathic pain.29 People who feel lonely take twice as much pain medication as those who do not feel lonely.30 Pain is negatively associated with life satisfaction, and feelings of pain can be reinforced by negative mood.31

Pain and delirium often coexist in the older adult population.2 Pain is a risk factor for delirium, and treatment of pain with the use of analgesics also may increase the risk of delirium.2 Delirium affects the ability of a patient to interact and participate in pain assessments, and thus serial assessments must be performed.2

As compared to those without pain, older adults with pain use more healthcare services, including multiple primary care provider and specialist visits, diagnostic testing, trips to the emergency department, and hospitalizations.5 Older U.S. adults with pain and multimorbidity had greater annual healthcare expenditures than those without pain.32 Additionally, compared to those with perceived health as fair or poor, U.S. adults with pain and better perceived health status had lower annual healthcare expenditures.15 Effective pain management leads to decreased morbidity and mortality, faster recovery, and shorter hospital stays, which ultimately leads to decreased healthcare expenditures.8

Pathophysiology

According to Lin and Siegler, “Pain is an interaction between excitatory and inhibitory neurological pathways that integrate information from nociceptive, inflammatory, and neuropathic and emotional components.”12 Pain can be either nociceptive due to stimulation of pain receptors, neuropathic in origin due to disturbances of the peripheral or central nervous system, or mixed pain that is a combination of both.14 Pain processing is achieved through transduction and transmission of a variety of mechanical, chemical, and thermal stimuli from the peripheral receptors to the brain.1 Chronic pain develops in the setting of unrelieved acute pain, which causes neuroplastic changes within the pain pathways. Therefore, effective and timely management of acute pain is essential.12

Pain consists of not only a sensory component but also an emotional component.2 The sensory component describes where a person locates the pain and how it feels, while the emotional component refers to the feelings and meaning associated with the pain.2 The experience of pain is influenced by many factors in both past and current social interactions.2 Additionally, the unique environmental and social circumstances that preceded hospitalization influence the experience of pain.12 Understanding the patient’s beliefs and attitudes toward pain are important in fully assessing pain.5 Genetic predisposition, gender, and mental processes, such as feelings and beliefs around pain, contribute to the interpretation of pain.29

Objective physical signs of pain include tachycardia, elevated blood pressure, diaphoresis, and anxiety.12 The effect of pain includes functional impairments, decreased appetite, impaired sleep, depression, and social isolation.6,7 Additionally, pain impairs activities of daily living, sleep quality, and overall quality of life.20 The most commonly affected aspects of daily life reported were sleep, general activity, and walking.20 Pain can be manifested in a variety of ways. Table 1 lists these manifestations of pain.33

Table 1. Examples of Manifestations of Pain |

|

The anatomical structures involved in pain processing undergo age-associated changes that alter the way in which pain is processed.1 Aging leads to reduced ability to detect harmful signals due to loss of the structure and function of peripheral and central nervous system pathways.6 There is a decrease in the number of myelinated delta nerve fibers that detect sharp localized pain, and these nerve fibers are replaced with non-neuronal glial cells that reduce the pain response.6,7 The majority of neuronal loss occurs within the neocortex and hippocampus, which influences pain perception.34 Additionally, the reduced conduction velocity of these neuronal fibers is associated with reduced sensitivity to pain and loss of proprioception, which ultimately leads to a higher risk of injury.1,6,7 Overall, there is a decrease in the number of synapses, receptors, and intracellular enzymes with age, leading to changes in neurologic function and pain perception.34

Aging also leads to an increased pain threshold, requiring a higher stimulus to induce pain, but the maximal intensity of pain a person can tolerate is either unchanged or reduced with aging.6 Additionally, older adults experience longer periods of hyperalgesia following a painful stimulus.6 This is related to dysfunction of pain modulatory and evaluation processes in the neural networks that leads to increased pain perception.35 The ability to recover from injury and resolution of pain, or neuroplasticity, is slowed in advancing age.6

There are various physiologic changes that occur as the body ages, and these physiologic changes affect how pain is both diagnosed and managed.8 Changes in organ function affect assessment of pain, perception of pain, and drug pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics.34 Changes occur in the cardiovascular, respiratory, renal, hepatic, and musculoskeletal systems. (See Table 2.)

Table 2. Physiologic Changes with Aging by Organ System and the Effect on Pain Management |

||

Organ System |

Changes with Aging |

Effect on Pain Management |

Cardiovascular |

|

|

Respiratory |

|

|

Renal |

|

|

Hepatic |

|

|

Musculoskeletal |

|

|

With increasing age, the cardiovascular system has decreased cardiac output and increased atherosclerosis.6,8 This leads to slower body distribution of drugs.8 Additionally, there is a higher risk of adverse coronary or vascular events with uncontrolled pain.6,8 The respiratory reserve decreases with age, leading to a higher risk of respiratory decompensation associated with pain.6,8 Additionally, there is a higher risk of respiratory depression with the use of pharmacologic analgesia.34

Changes in the renal system with age include glomerulosclerosis, renal cortical atrophy, and decreased glomerular filtration rate, which leads to decreased clearance of medications.8 Additionally, the changes in renal physiology can lead to reduced renal reserve for recovery from nephrotoxic medications.6,8 Renal function decreases by 1% per year after the age of 50 years, which affects the clearance of many medications.34 This decrease in renal function can be attributed to decreased renal blood flow, decreased renal mass, or a decrease in the number, length, and thickness of the renal tubules.34

As a person ages, the liver has fewer hepatocytes and reduced hepatic blood flow, which decreases the metabolism of drugs cleared through hepatic metabolism.6,8 This decrease in hepatic metabolism is attenuated in malnourished or frail patients.6 Liver metabolism is decreased by 30% to 40% in older adult patients, with a 1% decline in liver mass per year of life after the age of 50 years.34 The portal blood flow decreases by 33% by the age of 65 years as compared to younger patients.34 The first-pass hepatic metabolism also is affected by aging and decreases due to lower portal blood flow.34

Muscular atrophy with advancing age leads to decreased drug volume of distribution, leading to higher drug concentrations and higher risk of drug toxicity.8 There is an increased amount of fat in older patients, which leads to an increased volume of distribution and a longer duration of action in lipid-soluble medications.6,34 With advancing age, there is a decrease in the total body water, which means medications that are water soluble have a smaller volume of distribution, leading to an increased concentration and increased risk of adverse effects at lower doses.7,34 In addition to muscular atrophy, joints deteriorate with age, and lifestyle tends to become more sedentary, which contributes to musculoskeletal pain.36

Diagnosis of Pain

Common tools available for assessing pain include visual analog scales and numerical pain scoring scales.8 More complex assessment tools include the McGill Pain Questionnaire and the Brief Pain Inventory.7 Challenges associated with pain assessment include barriers such as impaired vision, hearing, and cognitive deficits.5 When assessing pain, it is important to consider a comprehensive assessment, including history and physical examination, to determine all the potential causes of pain.2 Obtaining collateral history from other caregivers or family members may be beneficial in older adult patients who are cognitively impaired.2 Despite extensive research on pain assessment tools as a whole, few studies consider the nuances of pain in older adults related to physiologic changes.1

The most well-validated pain assessment is self-reporting of pain, but these methods lead to dramatic underdetection and undertreatment of pain in patients with cognitive impairment.2,7,37 Prior to using a self-reporting assessment tool, a patient should be assessed for the ability to self-report.2 The ability to self-report should be reassessed frequently because the ability to report pain can fluctuate.2 Patients and caregivers often underestimate and under-report pain.7 A study evaluating nursing documentation of pain in patients with dementia found that pain reporting between patients with dementia and pain reported by nurses was inconsistent and there was no association between the two. This indicates that nurses may underestimate the type and severity of pain experienced by those patients with dementia and cognitive impairment.37 The study further showed that nurses commonly used numeric rating scales to assess pain in various stages of dementia rather than observational tools for pain assessment.37 This likely reflects a knowledge gap related to the application of different pain tools. Thus, it is vital to support training on pain assessment tools for use with older adult patients and those with cognitive impairments.37 Nurses are in a critical position to help assess pain and develop pain policies because they are the healthcare professionals who have the most contact with patients.19

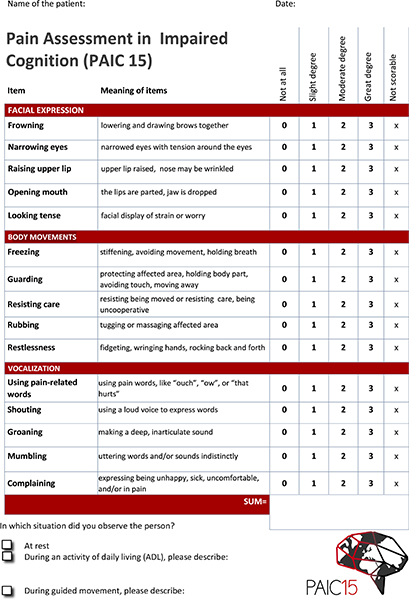

Observational tools were created to combine nonverbal behavior with physiologic changes to determine the level of pain. Nonverbal behavior evaluated includes facial expressions or changes in body language, while physiologic changes include heart rate and blood pressure.7 Despite the development of observational tools, there is no single tool that is widely accepted and internationally agreed upon for detecting pain.38 In a Spanish study where both physicians and nurses were surveyed, 35.7% of institutions did not have a recommended tool to assess pain in patients with cognitive impairment.9 Additionally, only 15% of surveyed nurses had received education related to pain assessment in cognitively impaired patients.9 Given the lack of an agreed upon observational pain assessment tool, the Pain Assessment in Impaired Cognition (PAIC 15) was developed. This novel assessment tool still requires further research on feasibility of use, but it shows promise in the future of observational pain assessment tools. PAIC 15 is a meta tool based on the most reliable and most valid aspects of previously established observational tools, such as ABBEY Pain Scale, ADD, CNPI, DS-DAT, DOLO-Plus, EPCA, MOBID2, NOPPAIN, PACSLAC, PAINAD, PADE, and PAINE.37 The PAIC 15 uses five facial expression items, five body movement items, and five vocalization items to determine a pain assessment value.38 (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1. Pain Assessment in Impaired Cognition (PAIC 15) |

|

Source: Kunz M, de Waal MWM, Achterberg WP, et al. The Pain Assessment in Impaired Cognition scale (PAIC15): A multidisciplinary and international approach to develop and test a meta-tool for pain assessment in impaired cognition, especially dementia. Eur J Pain 2020;24:204. Creative Commons CC BY 4.0 DEED https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ |

Management

Pain is multifactorial, therefore its treatment also must be.10 Multidisciplinary pain management with both pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic treatment is recommended, especially in patients who have experienced persistent pain despite standard therapies to reduce morbidity associated with polypharmacy.10,18 The goal is to provide analgesic pain relief with minimal side effects, such as avoiding delirium and further cognitive decline.8 There is a fine balance between the appropriate dosage for best relief and avoiding adverse effects of the medication.19 Overtreatment of pain can lead to cognitive decline and dysfunction, delirium, sedation, and falls.8 Despite a patient’s ability to report pain, when pain is likely, treatment should be initiated to avoid suffering, especially in those patients with delirium or cognitive impairment.2

The setting in which a patient is being treated must be considered. In the emergency department, pain should be treated promptly.12 Pain should be assessed, appropriate treatment should be initiated, and reassessment to ensure adequate analgesia must be performed.12 Factors that contribute to pain and may cause difficulty in treatment in the emergency department include noise, discomfort of the gurneys, multiple procedures and testing performed, and generalized anxiety associated with the acute illness and uncertainty of outcomes.12 Treatment of pain in a hospitalized patient must use both pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic modalities to maximize the functional status of the patient.12 The effectiveness of pharmacotherapy is enhanced by multimodality interventions, including patient education, physical therapy, psychosocial support, and alternative treatments.12 Treatment of pain for patients living in nursing facilities has no fundamental difference as compared to community dwelling adults.12 Residents admitted to a nursing facility for acute rehabilitation will have acute pain and will need frequent reassessments of pain and frequent changes in their pain management regimens as they recover.12

Of adults aged 60 years and older, 15.1% of reported use of one or more prescription pain medications within the last 30 days between 2015 and 2018.39 Of adults older than the age of 60 years, 8.2% reported opioid use.39 Polypharmacy prior to prescribing medications or offering pain altering interventions must be considered due to the risk of drug-drug interactions and side effects.7,8 Nonopioid therapies used for adults older than the age of 65 years include physical therapy/occupational therapy (22.2%), talk therapy (1.8%), complementary therapies (26.6%,) and other alternative interventions (40%).40

Pharmacologic Management

Table 3 is an overview of the pharmacologic therapies used in the treatment of pain. Acetaminophen is thought to be a centrally acting cyclooxygenase inhibitor that inhibits prostaglandin synthesis, although the mechanism of action still is a point of debate and a focus in research.7,8,41 It often is started as a monotherapy for mild ongoing pain and generally is well tolerated with limited side effects.7,8,41 Scheduling of acetaminophen can lead to reduced opioid requirements.8 Liver disease is a well-established relative contraindication to acetaminophen. If prescribed, daily dosing should be reduced by 50% to 75% because approximately 90% of acetaminophen is hepatically cleared.8,41

Table 3. Pharmacologic Therapies for the Treatment of Pain in Older Adults |

||

Drug Class |

Route of Administration |

Considerations and Adverse Reactions |

Acetaminophen |

|

|

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) |

|

|

Gabapentinoids |

|

|

Opioids |

|

|

Tricyclic antidepressants |

|

|

Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors |

|

|

Ketamine |

|

|

Lidocaine |

|

|

IV: intravenous; IM: intramuscular; GI: gastrointestinal |

||

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) inhibit cyclooxygenase in a variety of isoforms.8,41 NSAIDs must be used with caution in older adults because of the high risk of adverse reactions, including cardiovascular, renal, and gastrointestinal (GI) complications.8,41 Risk factors for toxicities associated with NSAID use include renal insufficiency, congestive heart failure, hypertension, and other comorbidities.41 In older adult patients, NSAIDs have been implicated in up to 25% of hospital admissions due to adverse drug reactions.41 NSAID-induced renal vasoconstriction and increased tubular sodium reabsorption can lead to fluid retention and possible exacerbation of congestive heart disease.41 Additionally, NSAIDs can contribute to worsening chronic renal failure, especially in those patients taking diuretics or angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors. Therefore, NSAIDs are contraindicated in patients with glomerular filtration rates less than 60 mL/min.8,41

GI adverse events related to NSAIDs include bleeding and ulceration, especially in patients taking aspirin or warfarin.41 GI bleeding also is nearly twice as common in patients older than age 65 years compared to younger patients.8 Cardiovascular side effects associated with NSAID use include a modest increase in blood pressure and increased risk of thrombotic events, including myocardial infarction or stroke.41 If prescribed, a dose reduction of 25% to 50% or interval increase between doses is recommended for older adult patients along with a clear stop date.7,8

Gabapentinoids bind the alpha 2 subunit of presynaptic voltage-gated calcium channels, resulting in inhibition and subsequent reduction of excitatory neurotransmitter release from the activated nociceptors.8 Gabapentinoids often are used in the treatment of neuropathic pain.8 Adverse reactions include dizziness and somnolence, which can increase the risk of falls and impaired cognitive function.8 Additionally, gabapentinoids are synergistic with central opioids and can result in increased rates of respiratory depression when used together.8

Opioids are derived from opium, which is harvested from the poppy Papaver somniferum.41 Opioids have been used in a variety of forms for thousands of years.41 Opioids produce analgesia primarily through interaction with mu receptors, which are present in the brain and spinal cord. While the primary site is the mu receptors, some opioids also may act at or have effects on kappa receptors, delta receptors, N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors, norepinephrine, serotonin, and sodium channels.41 Opioids can be agonists, antagonists, partial agonists, and mixed agonist-antagonists based on the interactions with the mu, kappa, and delta opioid receptors.41 Opioids are used commonly in both an inpatient and outpatient basis with proven benefit for the treatment of acute musculoskeletal pain, neuropathic pain, and cancer pain.41

Age-specific considerations for the use of opioids are related to side effects associated with opioid administration. Nausea, vomiting, and constipation are the most frequently reported side effects. Central side effects include drowsiness, dizziness, and sedation, which increase the risk of falls and fractures in older adults.41 Peripheral vasodilation can occur, leading to orthostatic hypotension and increased risk of falls.41 Respiratory depression is the most feared side effect, which can lead to apnea, hypoxia, and even death, especially in older adult patients who have a decreased respiratory reserve.6,8,41 Patients older than the age of 60 years have a two- to eight-fold increased risk of respiratory depression, falls, and fractures associated with opioid use.41 When dosing opioids, it is important to start at a low dose and titrate slowly.41 Older adult patients tend to require lower doses than younger individuals. However, this depends on previous opioid administration.41

Antidepressants, such as tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), noradrenergic and specific serotonergic antidepressants (NSSAs), and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), have been found to be effective agents, both in combination or as sole agents, in a variety of painful syndromes, particularly neuropathic pain.41 TCAs inhibit presynaptic reuptake of serotonin and norepinephrine and block cholinergic, adrenergic, histaminergic, and sodium channels.41 SNRIs and NSSAs increase the levels of both serotonin and norepinephrine, while SSRIs only affect serotonin.41 TCAs have been shown to be effective in the treatment of painful diabetic neuropathy, postherpetic neuralgia, polyneuropathy, and post-mastectomy pain. SNRIs and NSSAs have similar indications as TCAs but tend to have better side effect profiles for older adults.41

Ketamine is a well-established anesthetic that provides blockade of the NMDA receptor.8 Ketamine is used to improve pain control and help reduce the use of opioids in the treatment of acute pain.8 Side effects of ketamine include night terrors, confusion, hallucinations, and fear.8 Caution must be used with the use of ketamine in older adults because of the side effects of ketamine in a population that already is prone to the development of delirium.8 The recommended use of ketamine includes low-dose infusions rather than bolus doses to decrease the frequency of psychogenic events.

Lidocaine is an amide local anesthetic that can have systemic analgesic effects when given intravenously (IV) by hyperpolarization and decreased excitability of postsynaptic spinal dorsal horn neurons.8 Additionally, lidocaine causes suppression of spontaneous impulses generated from injured nerve fibers as well as anti-inflammatory and antihyperalgesic effects.8 Lidocaine clearance may decrease by 30% to 40% in older adult patients due to decreased hepatic blood flow; therefore, dose reduction or shorter infusions are advisable.8

Age should not be a deterrent for invasive measures, such as intra-articular injections, epidural injections, and joint replacements, to treat pain.5 Regional anesthesia can help reduce the adverse effects associated with systemic drugs; however, anatomic and neurophysiological changes seen with aging pose challenges to performing regional anesthesia.8 Neuraxial blocks are difficult to perform because of decreased intervertebral and epidural spaces as well as calcification of the ligamentum flavum, making needle advancement difficult. Despite the challenges to performing the blocks, postoperative epidural analgesia was noted to have superior pain control when compared to opioid medications, even in the older adult population.8 There is an increased risk of cephalad epidural solution spread causing hypotension; therefore, reduced infusion doses are recommended in older patients.8

Peripheral nerve blocks also are an effective method of controlling pain while minimizing side effects of systemic medications. Peripheral nerve blocks have a faster onset and longer duration of action due to the nerves becoming more susceptible to local anesthetics with age.8 Peripheral nerve blocks are helpful with injuries such as rib fracture and femoral neck fractures to help reduce the amount of systemic medications required to achieve pain control. However, with this increased susceptibility to local anesthetics, there is increased risk for nerve damage due to neurotoxic drug effects.8

Prescription drug abuse, diversion, overdose, and death have led to a public health crisis.42 The development of addiction in the context of a painful illness, especially in an older person, is unlikely. However, an older person’s medication may be sought after by family members for abuse or diversion.42 Identifiable risk factors must be considered, evaluated, and monitored when determining appropriate pain management for older adult patients.42

Nonpharmacologic Management

Nonpharmacologic treatment should be considered first line in conjunction with analgesic medications.5,7 These nonpharmacologic treatment modalities include heat or ice, massage therapy, physiotherapy, nutritional supplements, and alternative therapies.7,20 Nonpharmacologic treatments often are inexpensive, easy to perform, and have few risks or side effects.10 Additionally, they can build self-reliance and a sense of control over pain.43 For those older adults concerned with side effects of analgesics, nonpharmacologic interventions can be a useful alternative.43

Social support from family or caregivers can influence the pain experienced in older adults and decrease the unpleasantness compared with individuals living alone.16 Some pain relief can be experienced with distraction, but older patients do not have as much pain relief with distraction when compared to their younger counterparts.35,44 There still is some therapeutic benefit to the use of distraction in conjunction with other therapeutic measures.44

Alternative therapies, such as acupuncture, transcutaneous electrical stimulation, and qigong therapy, also can be considered.5 In a study of community dwelling older adults, pain intensities decreased significantly with interventions including acupressure, acupuncture, guided imagery, periosteal stimulation, qigong, and tai chi.43 Acupressure, guided imagery, qigong, and tai chi are interventions that can be performed by older adult patients themselves and are feasible to perform on a regular basis. Interventions such as acupuncture and periosteal stimulation require delivery on a regular basis by a trained professional, making these nonpharmacologic interventions less convenient.43 Yoga practice reduced all dimensions of pain during an eight-week intervention in older adult females, and these older adult females were noted to have improvement in sensory dimension and severity of pain.45 However, yoga in the short-term does not improve all aspects of pain.45

Keeping active is a central element of active or healthy aging.46 Low to moderate exercise increases physical function and joint range of motion.5 The American Geriatrics Society recommends prescribed exercise programs focusing on strength, flexibility, and endurance as adjunctive therapy.5 Physical activity can reverse frailty, improve mobility, and help reduce the fear of falls.47 In a study of older adults, participants reported better quality of life, better frailty status, and lower pain intensity after a physical activity intervention.47 Neuromuscular exercise, including functional performance, postural control, extremity muscle strength, balance, functional trunk and peripheral joint stability, and gait retraining, reduced pain and improved self-efficacy and physical function in older adults.48

Animal-assisted therapy in conjunction with physical therapy also was associated with a decrease in pain scale, and there was a high rate of follow-up and commitment to the animal-assisted therapy.49 A behavioral medicine-based approach in physical therapy focusing on the medical, physical, behavioral, cognitive, psychological, and social environment is recommended in the older adult population because it has positive effects on pain-related disability, pain severity, health-related quality of life, physical activity, self-efficacy, and management of everyday life.46 In a study looking at the behavioral medicine approach in physical therapy, older adult, frail patients were noted to have decreased pain-related disability, decreased pain severity, fewer falls, and reduced intake of pain medication during behavioral medicine physical intervention.46

Psychosocial intervention, such as self-management interventions, cognitive behavioral therapy, mindfulness meditation, and guided imagery, have been implicated in pain management practices.5 Psychosocial intervention can help stimulate the release of pain-modulating neurotransmitters such as norepinephrine, serotonin, or endogenous opiates.50 These interventions were noted to have significant reductions in observed pain in patients with dementia.50 Peer-led pain management programs did show a significant increase in self-pain efficacy, or the patient’s belief in his or her ability to accomplish daily tasks in spite of pain.51 Older adults were more capable of handling their daily tasks and pain became less of a hindrance in their daily life, allowing them to enjoy their lives more.51 In a study of older adult patients with low back pain, education was found to have positive effects on older people regardless of the type of education, but education alone does not demonstrate a statistically significant improvement in pain, disability, and quality of life; therefore, education should be used in conjunction with other therapies.52,53

Summary

With a projected 1.3 billion older adults by the year 2040, pain recognition, assessment, and treatment must be a priority for healthcare initiatives. Further education must be delivered to patients, caregivers, and healthcare professionals alike to understand that pain is not an inevitable and untreatable consequence of aging. While self-reporting pain is the most accurate for those who can report, further investigation must be performed to determine an appropriate observational tool to accurately recognize pain in those with cognitive impairments. Given challenges associated with aging, such as physiologic changes and comorbidities, multimodal pain management of both pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic interventions must be considered to balance between pain management and side effects.

REFERENCES

- Tinnirello A, Mazzoleni S, Santi C. Chronic pain in the elderly: Mechanisms and distinctive teatures. Biomolecules 2021;11:1256.

- Sampson EL, West E, Fischer T. Pain and delirium: Mechanisms, assessment, and management. Eur Geriatr Med 2020;11:45-52.

- Ray BM, Kelleran KJ, Eubanks JE, et al. The relationship between physical activity and pain in U.S. adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2023;55:497-506.

- Achterberg WP. How can the quality of life of older patients living with chronic pain be improved? Pain Manag 2019;9:431-433.

- Mehta SS, Ayers ER, Carrington Reid M. Effective Approaches for Pain Relief in Older Adults. Springer eBooks. Published online Dec. 14, 2018.

- Mullins S, Hosseini F, Gibson W, Thake M. Physiological changes from ageing regarding pain perception and its impact on pain management for older adults. Clin Med (Lond) 2022;22:307-310.

- Hosseini F, Mullins S, Gibson W, Thake M. Acute pain management for older adults. Clin Med 2022;22:302-306.

- Rajan J, Behrends M. Acute pain in older adults: Recommendations for assessment and treatment. Anesthesiol Clin 2019;37:507-520.

- Giménez-Llort L, Bernal ML, Docking R, et al. Pain in older adults with dementia: A survey in Spain. Front Neurol 2020;11:592366.

- González-Vaca J, Hernández MG, Cobo CS, et al. Non-pharmacological interventions to reduce pain in dementia: A quasi-experimental study. Appl Nurs Res 2022;63:151546.

- Harkin D, Coates V, Brown D. Exploring ways to enhance pain management for older people with dementia in acute care settings using a Participatory Action Research approach. Int J Older People Nurs 2022;17:e12487.

- Lin RJ, Siegler EL. Acute pain management in older adults. In: Cordts GA, Christo PJ, eds. Effective Treatments for Pain in the Older Patient. Springer Science + Business Media;2018:35-52.

- Li CY, Lin WC, Lu CY, et al. Prevalence of pain in community-dwelling older adults with hypertension in the United States. Sci Rep 2022;12:8387.

- Purwata TE, Rachmawati Emril D, Yudiyanta Y, Pinzon R. Characteristics of pain and comorbidities in geriatric subjects in Indonesia: A hospital-based national clinical survey. Romanian J Neurol 2022;21:158-162.

- Axon DR, Kamel A. Patterns of healthcare expenditures among older United States adults with pain and different perceived health status. Healthcare (Basel) 2021;9:1327.

- Dagnino APA, Campos MM. Chronic pain in the elderly: Mechanisms and perspectives. Front Hum Neurosci 2022;16:736688.

- Mallon T, Eisele M, König HH, et al. Lifestyle aspects as a predictor of pain among oldest-old primary care patients – A longitudinal cohort study. Clin Interv Aging 2019;14:1881-1888.

- Chen N, Farrell M, Kendall S, et al. The pain clinic for older people. Pain Med 2022;24:182-187.

- Arazi S, Rashidi F, Raiesifar A, et al. The effect of a non-pharmacological multicomponent pain management program on pain intensity and quality of life in community-dwelling elderly men with chronic musculoskeletal pain. Pain Manag Nurs 2023;24:311-317.

- Li X, Zhu W, Li J, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of chronic pain in the Chinese community-dwelling elderly: A cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr 2021;21:534.

- Wallace B, Singer D, Kullgren J, et al. Arthritis and joint pain. University of Michigan National Poll on Healthy Aging. September 2022. https://www.healthyagingpoll.org/reports-more/report/arthritis-and-joint-pain

- de Souza IMB, Sakaguchi TF, Yuan SLK, et al. Prevalence of low back pain in the elderly population: A systematic review. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2019;74:e789.

- Nawai A. Chronic pain management among older adults: A scoping review. SAGE Open Nurs 2019;5:2377960819874259.

- Butera KA, Roff SR, Buford TW, Cruz-Almeida Y. The impact of multisite pain on functional outcomes in older adults: Biopsychosocial considerations. J Pain Res 2019;12:1115-1125.

- Rundell SD, Patel KV, Krook MA, et al. Multi-site pain is associated with long-term patient-reported outcomes in older adults with persistent back pain. Pain Med 2019;20:1898-1906.

- Qiu Y, Li H, Yang Z, et al. The prevalence and economic burden of pain on middle-aged and elderly Chinese people: Results from the China health and retirement longitudinal study. BMC Health Serv Res 2020;20:600.

- Stokes AC, Xie W, Lundberg DJ, et al. Increases in BMI and chronic pain for US adults in midlife, 1992 to 2016. SSM Popul Health 2020;12:100644.

- Imai R, Imaoka M, Nakao H, et al. Association between chronic pain and pre-frailty in Japanese community-dwelling older adults: A cross-sectional study. Sanada K, ed. PLoS One 2020;15:e0236111.

- Michaelides A, Zis P. Depression, anxiety and acute pain: Links and management challenges. Postgrad Med 2019;131:438-444.

- Carrasco PM, Crespo DP, Rubio CM, Montenegro-Peña M. Loneliness in the elderly: Association with health variables, pain, and cognitive performance. A population-based study. Clinica y Salud 2022;33:51-58.

- Pan L, Li L, Peng H, et al. Association of depressive symptoms with marital status among the middle-aged and elderly in rural China – Serial mediating effects of sleep time, pain and life satisfaction. J Affect Disord 2022;303:52-57.

- Marupuru S, Axon DR. Association of multimorbidity on healthcare expenditures among older United States adults with pain. J Aging Health 2021;33:741-750.

- Cravello L, Di Santo S, Varrassi G, et al. Chronic pain in the elderly with cognitive decline: A narrative review. Pain Ther 2019;8:53-65.

- Bemben NM, Mary Lynn McPherson. Unique Physiologic Considerations. In: Cordts GA, Christo PJ, eds. Effective Treatments for Pain in the Older Patient. Springer; 2019:53-69.

- González-Roldán AM, Terrasa JL, Sitges C, et al. Age-related changes in pain perception are associated with altered functional connectivity during resting state. Front Aging Neurosci 2020;12:116.

- El-Tallawy SN, Nalamasu R, Salem GI, et al. Management of musculoskeletal pain: An update with emphasis on chronic musculoskeletal pain. Pain Ther 2021;10:181-209.

- Kunz M, de Waal MWM, Achterberg WP, et al. The Pain Assessment in Impaired Cognition scale (PAIC15): A multidisciplinary and international approach to develop and test a meta‐tool for pain assessment in impaired cognition, especially dementia. Eur J Pain 2019;24:192-208.

- Tsai YIP, Browne G, Inder KJ. Documented nursing practices of pain assessment and management when communicating about pain in dementia care. J Adv Nurs 2022;78:3174-3186.

- Hales CM, Martin CB, Gu Q. Prevalence of prescription pain medication use among adults: United States, 2015-2018. NCHS Data Brief 2020;369:1-8.

- Groenewald CB, Murray CB, Battaglia M, et al. Prevalence of pain management techniques among adults with chronic pain in the United States, 2019. JAMA Netw Open 2022;5:e2146697.

- Carinci AJ, Pritzlaff S, Moore A. Recommendations for classes of medications in older adults. In: Cordts GA, Christo PJ, eds. Effective Treatments for Pain in the Older Patient. Springer; 2019:109-130. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-8827-3_6

- Passik SD, Rzetelny A, Kirsh KL. Assessing and managing addiction risk in older adults with pain. In: Cordts GA, Christo PJ, eds. Effective Treatments for Pain in the Older Patient. Springer eBooks. Springer; 2019:177-192.

- Tang SK, Tse MMY, Leung SF, Fotis T. The effectiveness, suitability, and sustainability of non-pharmacological methods of managing pain in community-dwelling older adults: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2019;19:1488.

- González-Roldán AM, Terrasa JL, Sitges C, et al. Alterations in neural responses and pain perception in older adults during distraction. Psychosom Med 2020;82:869-876.

- Mirzaei T, Tavakoli O, Ravari A. The effect of yoga on musculoskeletal pain in elderly females: A clinical trial. Iranian Rehabilitation Journal 2021;2(Special Issue):55-64.

- Cederbom S, Leveille SG, Bergland A. Effects of a behavioral medicine intervention on pain, health, and behavior among community-dwelling older adults: A randomized controlled trial. Clin Interv Aging 2019;14:1207-1220.

- Otones P, García E, Sanz T, Pedraz A. A physical activity program versus usual care in the management of quality of life for pre-frail older adults with chronic pain: Randomized controlled trial. BMC Geriatr 2020;20:1-9.

- Sit RWS, Choi SYK, Wang B, et al. Neuromuscular exercise for chronic musculoskeletal pain in older people: A randomised controlled trial in primary care in Hong Kong. Br J Gen Pract 2020;71:226-236.

- Rodrigo-Claverol M, Casanova-Gonzalvo C, Malla-Clua B, et al. Animal-assisted intervention improves pain perception in polymedicated geriatric patients with chronic joint pain: A clinical trial. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019;16:2843.

- Pu L, Moyle W, Jones C, Todorovic M. Psychosocial interventions for pain management in older adults with dementia: A systematic review of randomised controlled trials. J Adv Nurs 2019;75:1608-1620.

- Tse MMY, Ng SSM, Lee PH, et al. Effectiveness of a peer-led pain management program in relieving chronic pain and enhancing pain self-efficacy among older adults: A clustered randomized controlled trial. Front Med (Lausanne) 2021;8:709141.

- Zahari Z, Ishak A, Justine M. The effectiveness of patient education in improving pain, disability and quality of life among older people with low back pain: A systematic review. J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil 2020;33:245-254.

- Öztürk Ö, Bombacı H, Keçeci T, Algun ZC. Effects of additional action observation to an exercise program in patients with chronic pain due to knee osteoarthritis: A randomized-controlled trial. Musculoskelet Sci Pract 2021;52:102334.

Many older adults experience pain, but there are limited guidelines to appropriately manage their pain. Additionally, assessment of pain control in older adult patients can be difficult because of impairments in cognition, hearing, and sight. Increasingly, acute care providers are challenged to manage pain in this unique population. This article will discuss the epidemiology and etiology of pain in the older adult population, the pathophysiology, tools for diagnosing pain in older adults with cognitive impairment, and appropriate multimodal pain management for older adult patients.

Subscribe Now for Access

You have reached your article limit for the month. We hope you found our articles both enjoyable and insightful. For information on new subscriptions, product trials, alternative billing arrangements or group and site discounts please call 800-688-2421. We look forward to having you as a long-term member of the Relias Media community.