By Stan Deresinski, MD, FACP, FIDSA

Clinical Professor of Medicine, Stanford University

SYNOPSIS: More than 1 million people acquired enteric infections in the course of almost 40,000 outbreaks in the United States over the 11 years of this study.

SOURCE: Wikswo ME, Roberts V, Marsh Z, et al. Enteric illness outbreaks reported through the National Outbreak Reporting System-United States, 2009-2019. Clin Infect Dis2022;74:1906-1913.

In 2009, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) enhanced its outbreak surveillance activities by establishing the National Outbreak Reporting System (NORS). Using NORS, Wikswo and colleagues analyzed 38,395 outbreaks of enteric illness resulting in more than 1 million infections over its first 11 years. The annual number of outbreaks increased from 1,942 in the first year and reached a peak of 4,145 in 2016, after which the numbers plateaued.

Person-to-person transmission and foodborne transmission accounted for 62% and 24% of outbreaks, respectively. Multistate outbreaks were associated most often with foodborne transmission, which accounted for 68% of outbreaks, or with animal contact (21%). Norovirus accounted for 59% of the 38,395 outbreaks, with Salmonella a distant second at 6%.1 These were followed by Shigella (3%), Escherichia coli (2%), and Campylobacter (2%).

Person-to-person transmission accounted for 79% of norovirus outbreaks and foodborne transmission for 14%. One-half (53%) of norovirus outbreaks occurred in long-term care facilities, while 11% occurred in schools/daycare centers and 19% in restaurants. The median number of cases in each norovirus outbreak was 22, which was more than three times higher than for any other pathogen outbreak. Although norovirus accounted for the greatest number of deaths and hospitalizations, the case fatality and hospitalization rates were only 0.20% and 20.9%, respectively.

E. coli outbreaks most commonly originated in private homes (19%) and schools/daycare centers (18%) and most often were foodborne. They were associated with the highest case fatality rates (0.47%) and rate of hospitalization (22.8%), presumably related to Shiga toxin production.

Four-fifths of transmission in Shigella outbreaks resulted from person-to-person transmission, with two-thirds occurring in schools/daycare centers and 8% in private homes, with foodborne transmission being most common. The case fatality rate was only 0.02%. The case fatality rate for Campylobacter infection, which most often was foodborne, also was only 0.02%, representing just one death, but the hospitalization rate was 9%. Salmonella outbreaks most often centered on restaurants (23%) and private homes (20%) and were associated with a case fatality rate of 0.20% and hospitalization rate of 20.9%.

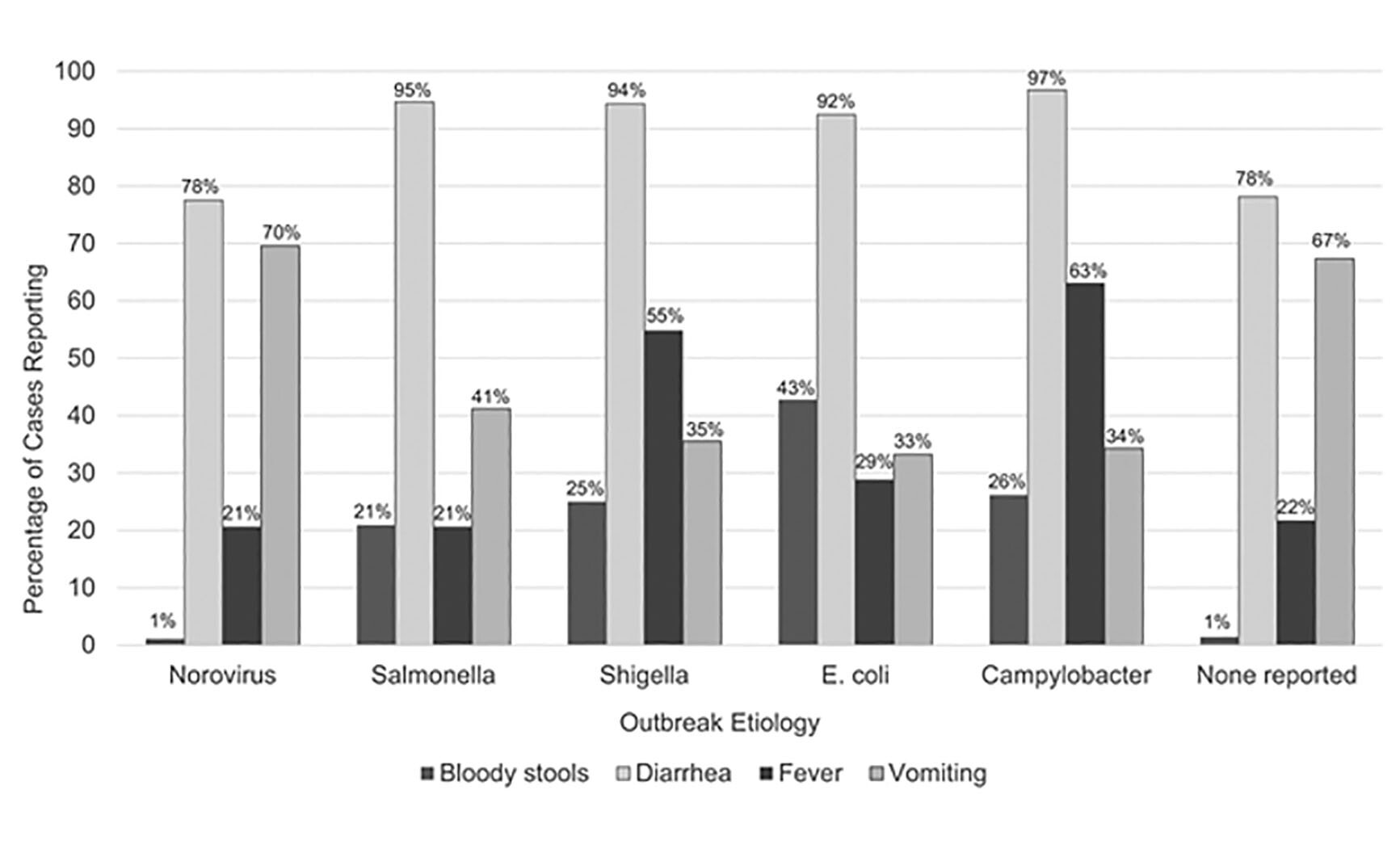

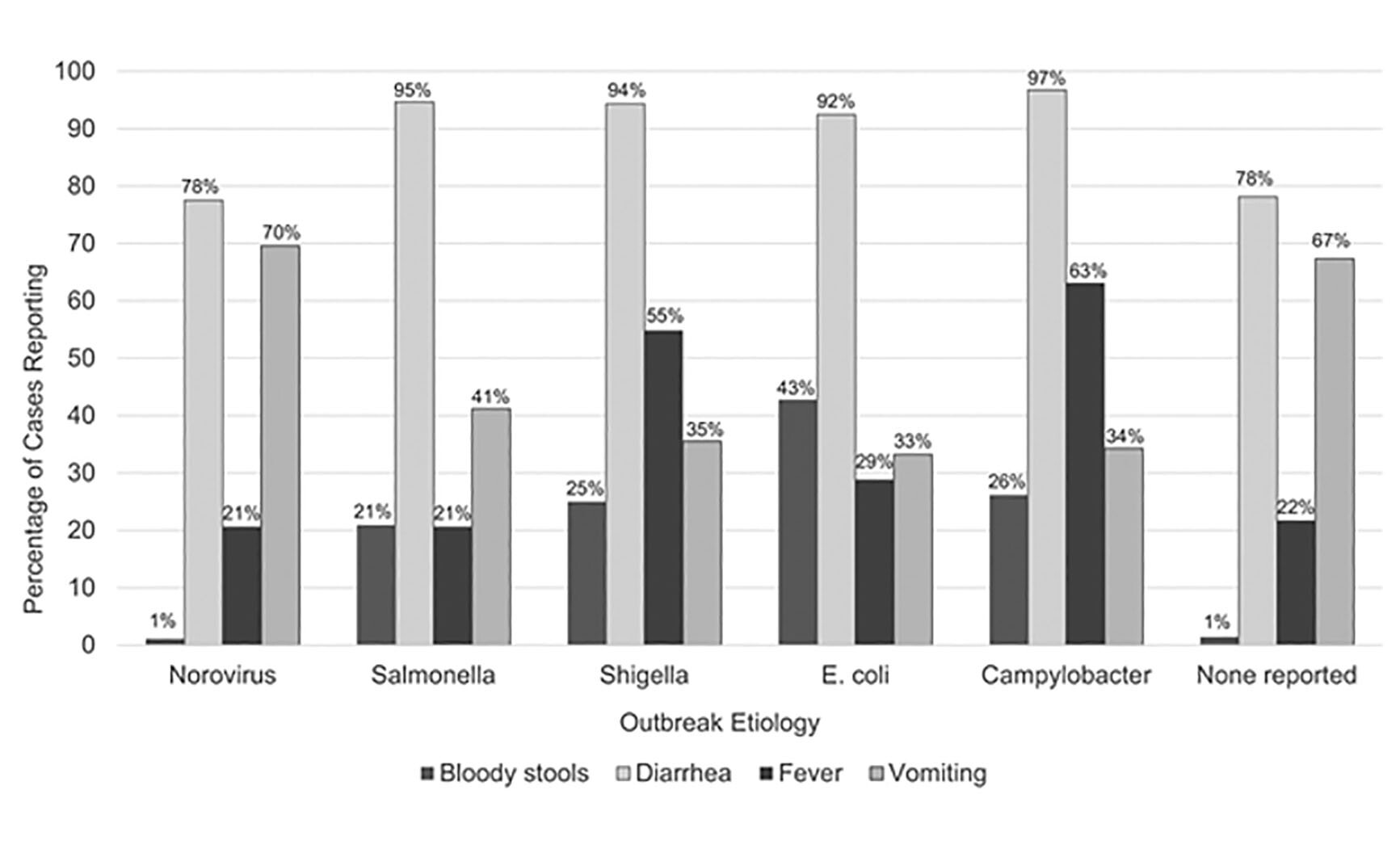

The most frequent symptoms associated with each etiology are depicted in Figure 1. One difference of note is the high frequency of vomiting in norovirus infection — not unexpected for an illness that has been called winter vomiting disease. Fever was more common with Shigella and Campylobacter infections, and bloody stools occurred in 20% to 30% of Salmonella, Shigella, and Campylobacter infections, while this was reported in 43% of E. coli infections.

Figure 1: Symptoms Reported by Case-Patients in Outbreaks of Selected Confirmed or Suspected Etiologies, 2009-2019 |

|

Published by Oxford University Press for the Infectious Diseases Society of America 2021. This work is written by (a) US Government employee(s) and is in the public domain in the US. Published by Oxford University Press for the Infectious Diseases Society of America 2021. |

COMMENTARY

More than 1 million people acquired enteric infections in the course of almost 40,000 outbreaks in the United States over the 11 years of this study. Not unexpectedly, norovirus was the most common cause. Its targeting of long-term care facilities can be catastrophic and is associated with great morbidity as a consequence of the associated elderly, frail populations.1

The multiple modes and settings of transmission of the enteric pathogens, as well as the complexities of the food chain, all complicate the public health approach to the problem. In addition, treatment of the bacterial infections is further complicated by the progressive emergence of antibiotic resistance in Salmonella, Shigella, and Campylobacter.

REFERENCE

- Robilotti E, Deresinski S, Pinsky BA. Norovirus. Clin Microbiol Rev 2015;28:134-164.