By Stacey Kusterbeck

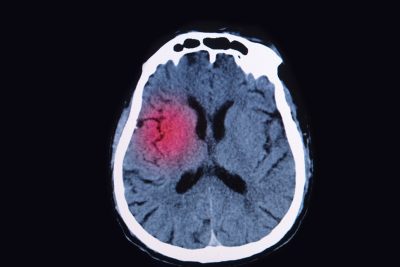

Some ethics consultations involve brain-injured patients who are unresponsive, and contain discussions center around withdrawing life-sustaining interventions. At least for some of those patients, there may be more hope for recovery than previously was believed to be the case, a recent study suggests. A surprising number of patients with brain injury who are unresponsive to behavioral commands can perform cognitive tasks that can be detected with neurotechnology, researchers found.1 For 241 patients with disorders of consciousness, researchers assessed volitional response to commands on functional magnetic resonance imaging or electroencephalography. The researchers detected cognitive motor dissociation in 25% of participants without an observable response to verbal commands.

Medical Ethics Advisor (MEA) spoke with Joseph J. Fins, MD, MACP, FRCP, one of the study authors, about what this means for hospital-based ethicists. Fins is chief of the division of medical ethics and the E. William Davis, Jr., MD, Professor of Medical Ethics at Weill Cornell Medical College and Solomon Center Distinguished Scholar in Medicine, Bioethics, and the Law, and a visiting professor of law at Yale Law School. Fins is author of Rights Come to Mind: Brain Injury, Ethics, and the Struggle for Consciousness (Cambridge University Press; 2015).

MEA: What are the clinical and ethical implications of the study?

Fins: Our study suggests that we’re underestimating covert consciousness in this population of patients that, heretofore, we had written off as being unconscious.

First, the study was investigational. It’s not ready for clinical dissemination yet, because we have to better understand the test characteristics. It, however, does show that a prevalence of 25% of patients, who were thought to be in a coma or a vegetative state, may have the ability to respond to volitional commands. It’s not a passive response. We asked people to imagine playing tennis or walking through their house, and you have to hold that in memory and then execute the task. We think that the presence of cognitive motor dissociation may actually be higher, because it’s harder to follow those commands than just be covertly conscious.

The mortality rate of acute traumatic brain injury for people is about 30%. But about 70% of those deaths are accounted for by a decision to withdraw or withhold life-sustaining therapy.2 Some of those people certainly would have died. But all of them will die who have life-sustaining therapy withdrawn or withheld.

Historically, in routine medical care, when the person loses the ability to respond and loses consciousness, that usually looks like the end of a progression of illness. But in brain injury, the process starts with loss of consciousness. And you may recover. Clinicians really need to be retooled when they think about these brain injuries. Some of it is scientific retooling, and some of it is a change in their cultural expectations.

This study shows that there is heterogeneity in brain states that appear the same at the bedside. Under the hood, patients are different than they appear to be. And that difference really makes a difference as far as prognosis — and, perhaps, in responsiveness to therapeutics.

MEA: What is the challenge for ethicists? Is a change in mindset necessary for these patients?

Fins: The challenge is that you are going up against a cultural expectation that these people are not going to get better. The right to die was established in the context of severe brain injury. There was a presumption of futility. If you go back and read the Quinlan decision, it was the loss of a “cognitive sapient state” that became a moral warrant to withdraw life-sustaining therapy. For years, we overgeneralized the futility of those patients who may not be as they appear.

The right to die began in a vegetative state. But not everybody who appears vegetative is — and not all of them will die. Many could get better, especially people in a minimally conscious state or with cognitive motor dissociation.

We’ve kind of ignored this population. Part of what we have to do is overcome denial, so that we appreciate the hidden potential for recovery that some of these patients have.

We do know if you’ve got cognitive motor dissociation, you’ve got a better prognosis one year later than if you don’t. We do know that. So, there are prognostic implications. And there are normative implications. If the family knows that their loved one can hear their voices, they’re going to be more hopeful. They might engage them more, and that might also be beneficial to the patient.

This is something we’ve been talking about in the neuroethics/disorders of consciousness research space, for many years. But the reason this study, which took 16 years to do, is so important, is that it’s a multicenter study with large numbers of patients, and it was published in a leading journal. And the prevalence that we demonstrated is a significant prevalence of 25%. What started off as sort of a niche issue is now something that we have to be deeply concerned about. Now that we know, we can’t look away.

We should celebrate that we now have the ability to look inside the injured brain. Before that, we were stuck with limits of the clinical exam. And we now know that 25% of people who appear unresponsive have cognitive motor dissociation.

We were living in a realm of relative ignorance. We thought that these people had no prognosis. But now we are beginning to appreciate that there is heterogeneity in patients with disorders of consciousness.

MEA: What practice changes can ethicists advocate for on behalf of these patients?

Fins: These patients will often be ignored and won’t get evaluated properly or get the rehabilitation that they need. This data is a wakeup call for how we evaluate care of these patients.

If you have cognitive motor dissociation and you have intact neural networks, it’s also likely that you can perceive pain. People who are thought to be vegetative often don’t get pain medicine, because they’re thought to be insensate, and therefore can’t experience pain. But if 25% of them have intact neural networks, then you are not treating pain in 25% of these patients. At the very least, we can advocate for universal pain precautions, and make sure patients get adequate analgesia for procedures and monitoring for evidence of pain.

The other thing is being at the bedside and talking about these patients. They appear unconscious at the bedside, but they may not be unconscious. I have a rule of not talking at the bedside of the patients unless I’m doing positive talk, because I don’t really know for sure when they can hear you. Clinical ethicists can remind their colleagues that their words may be heard and [are] iatrogenic. Basically, if it is negative talk, take it outside the room. Just imagine the isolation of hearing those comments and being unable to respond.

MEA: What do ethicists need to do differently when consulting on these cases?

Fins: Most clinical ethicists have not been trained in this area. It needs to be incorporated into the clinical ethics educational curriculum. I have written a guide in Plum and Posner’s Diagnosis of Stupor and Coma.3

The right to die and the vegetative state in Quinlan is such a big part of bioethics perceived wisdom. It’s what we know. The establishment of the right to die was critical, but there is another aspect to the story. And the reality is what we thought we knew about disorders of consciousness is incomplete. It’s kind of a paradigm shift. Because once you know about the possibility of cognitive motor dissociation, you need to think differently about these patients.

What will eventually happen is we need to do surveillance so patients who we think might have covert consciousness are identified. That gets into the conversation about care decisions. At a minimum, that includes making sure these patients get pain management.

In talking to families of patients in cognitive motor dissociation, there is more hope. But we also don’t want to promote false hope. It needs to be a very nuanced conversation. And the first step for bioethicists to have this conversation is to take responsibility for being educated about this. The problem is most bioethicists are not prepared to have this conversation. We don’t want to have uninformed conversations or premature discussions about prognosis before patients have declared themselves.

As we think about the notion of informed consent and informed refusal, the key word is informed. If bioethicists are not informed about this complexity, there is no way they can secure informed consent or refusal from surrogates. For bioethicists, basic information about these brain states is essential. Both clinicians and ethics have to be knowledgeable, and skilled enough, to guide families through this maze.

Bioethicists have a professional responsibility to become educated about this, just as they would for other diseases or conditions. If you don’t understand the facts, your ethics are going to be off. If a well-intentioned ethicist doesn’t understand the possibility of cognitive motor dissociation, it could be problematic. More likely than not, you’re going to be overly nihilistic. The data suggests that 70% of people will have their care withdrawn. The point is, we have to be more circumspect about that. We need to let people declare themselves.

This study is a wakeup call for enhanced education of clinical ethicists about disorders of consciousness, in all their complexity. You shouldn’t be consulting on things you don’t truly understand. There is an obligation here to collaborate with the neurologists and the neuropsychologists at your institution. And even there, this is a challenge. Even a lot of clinical doctors and neurologists don’t know this. It takes time to disseminate the information. Futility was overgeneralized to all people who appeared to be in a vegetative state. Some of those people are not in a vegetative state.

It is critical that my colleagues in clinical ethics take this seriously and understand how important this is. The reality is, there are ethical and legal implications to getting it wrong.

It’s kind of like the germ theory. People didn’t believe in the germ theory until they did. This data represents a sea change in how we understand brain injury. It is a nuance that we need to accommodate. New knowledge makes you realize that what you thought was OK is no longer OK.

You assume that someone’s in a vegetative state and has been unconscious for a long time, and you assume it will be forever. Then you realize it maybe it isn’t forever. Maybe they aren’t even vegetative. And maybe things can change for the better.

References

1. Bodien YG, Allanson J, Cardone P, et al. Cognitive motor dissociation in disorders of consciousness. N Engl J Med. 2024;391(7):598-608.

2. Fins JJ. Disorders of consciousness in clinical practice: Ethical, legal and policy considerations. In: Posner JP, Saper CB, Schiff ND, et al. Plum and Posner’s Diagnosis of Stupor and Coma, Fifth Edition. Oxford University Press; 2019:449-477.

3. Turgeon AF, Lauzier F, Simard JF, et al. Mortality associated with withdrawal of life-sustaining therapy for patients with severe traumatic brain injury: A Canadian multicentre cohort study. CMAJ 2011;183(14):1581-1588.

Some ethics consultations involve brain-injured patients who are unresponsive, and contain discussions center around withdrawing life-sustaining interventions. At least for some of those patients, there may be more hope for recovery than previously was believed to be the case, a recent study suggests.

Subscribe Now for Access

You have reached your article limit for the month. We hope you found our articles both enjoyable and insightful. For information on new subscriptions, product trials, alternative billing arrangements or group and site discounts please call 800-688-2421. We look forward to having you as a long-term member of the Relias Media community.