Authors

Monique De Araujo, MD, MPH

Acute Care Pediatrician, Mountain View Pediatrics, Packard Children's Health Alliance, CA

N. Ewen Wang, MD

Professor of Emergency Medicine and Pediatrics, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA

Brittany Boswell, MD

Clinical Assistant Professor of Pediatric Emergency Medicine, Department of Emergency Medicine, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA

Peer Reviewer

Katherine Baranowski, MD, FAAP, FACEP

Chief, Division of Pediatric Emergency Medicine, Department of Emergency Medicine, New Jersey Medical School, Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, Newark

Executive Summary

- Between 2016 and 2022, anaphylaxis-related emergency department (ED) presentations doubled among all patients and tripled among children, with children younger than 4 years of age reported to have close to a three times higher overall incidence of anaphylaxis.

- Food is the most common trigger for anaphylaxis in infants and children. When food is the trigger for anaphylaxis, the time to onset of symptoms often is five minutes to two hours, averaging 30 minutes from ingestion.

- A U.S. study suggests that only 60% of likely anaphylactic events were recognized as anaphylaxis. This is in part because vague or nonspecific symptoms and atypical or variable presentations of anaphylaxis may contribute to delays in diagnosis and because fatal anaphylaxis may present without skin or cardiovascular manifestations. There is consensus that a high clinical suspicion for life-threatening allergic reaction or anaphylaxis is enough to warrant administration of intramuscular (IM) epinephrine and that there is no absolute contraindication to the use of epinephrine in anaphylaxis.

- One of the dangers of anaphylaxis is the risk of a biphasic reaction. A biphasic reaction is the recurrence of anaphylaxis within one to 72 hours after resolution of symptoms from the initial episode and without exposure to new allergens. Risk factors that have been associated with biphasic reaction include severe features or hypotension, delayed administration of epinephrine, requiring multiple doses of epinephrine, and unknown triggers.

- The typical presentation of anaphylaxis most often includes skin and mucosa involvement (62% to 90%), followed by respiratory symptoms (45% to 70%) and gastrointestinal symptoms (25% to 45%). Common cutaneous manifestations include urticaria, pruritus, and angioedema.

- Worrisome presentations of anaphylaxis include rapid progression (within minutes), difficulty breathing, upper airway involvement, hypotension, or shock.

- Triage should include the removal of a potential trigger; administration of IM epinephrine; assessment of airway, breathing, and circulation; assessment of skin and mental status; and positioning the patient.

- IM epinephrine is the single most important first-line intervention for anaphylaxis. It reverses bronchoconstriction and mucosal edema, increases systemic vascular resistance, increases cardiac output (inotropy and chronotropy), and stabilizes mast cells and basophils (inflammatory mediators).

- The exact observation period for patients presenting in anaphylaxis is another area of uncertainty. There is consensus that all patients should be observed at least until showing significant symptom improvement, if not resolution. However, recommendations range from one to eight hours of direct observation and monitoring, or admission, pending patient presentation, anaphylaxis severity, and risk of biphasic reaction, among other factors. Therefore, the length of observation after improvement or resolution of symptoms should be individualized, taking into account patient-specific characteristics.

- The aim is for 100% of patients who receive a diagnosis of or are treated for anaphylaxis to leave the ED with a new or active prescription for IM epinephrine.

- Refer all patients presenting for or with suspicion for anaphylaxis to an allergist or immunologist.

The incidence of anaphylaxis, a rapidly progressive and potentially fatal disease, is increasing and unfortunately common in children. It is imperative that all acute care providers are prepared to recognize, quickly treat, and ensure appropriate follow-up for these patients. The authors focus on anaphylaxis, its presentation, management, and disposition from the ED.

— Ann M. Dietrich, MD, FAAP, FACEP, Editor

Introduction

Allergic reactions range from mild to life-threatening. The most severe and life-threatening presentation of allergic reactions is anaphylaxis.1 This is an important pediatric issue because more than 25% of cases of anaphylaxis are in children.2 In 2016, the average cost for an anaphylaxis-related emergency department (ED) visit was estimated at $1,419 per child per visit.3 The rate of anaphylaxis-related pediatric ED cases has been steadily increasing since then.4,5

Epinephrine is the most important treatment for anaphylaxis and should not be delayed by adjunct treatment. Challenges with appropriate anaphylaxis management include underuse of epinephrine, delay in the immediate administration of epinephrine when clinical suspicion for anaphylaxis is high, and the need for appropriate disposition and follow-up after presentation to the ED.6-9

The incidence of anaphylaxis is increasing, admission rates are decreasing, and anaphylaxis can be rapidly progressing and fatal.4,5 Therefore, it is paramount for emergency medicine physicians to recognize, quickly treat, and ensure appropriate follow-up for these patients. We will focus on anaphylaxis, its presentation, management, and disposition from the ED.

Epidemiology

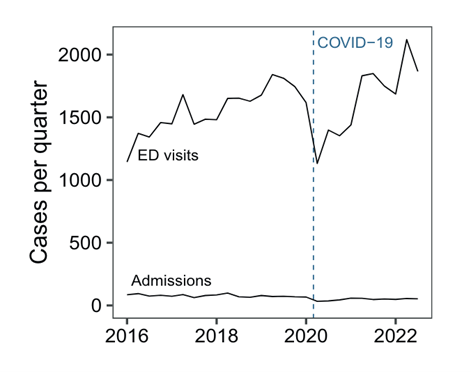

Anaphylaxis is estimated to occur in 1.6% to 5.1% of the general U.S. population.2,9,10 The prevalence of anaphylaxis is increasing, both in the United States and globally.1,4,11-13 In 2016, 3.5 per 10,000 pediatric ED visits were for anaphylaxis — a 150% growth compared to 2010.3 Between 2016 and 2022, anaphylaxis-related ED presentations doubled among all patients and tripled among children.4 (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1. Trends in Pediatric Emergency Department (ED) Visits and Hospitalizations for Anaphylaxis from 2016 to 2022 Across 48 Hospitals |

|

Reprinted with permission from Dribin TE, Neuman MI, Schnadower D, et al. Trends and variation in pediatric anaphylaxis care from 2016 to 2022. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2023;11:1184-1189. |

Children younger than 4 years of age have been reported to have close to a three times higher overall incidence of anaphylaxis than those in other age groups and are at the highest risk for hospitalization because of anaphylaxis.9,13 Anaphylaxis can recur in 26.5% to 54% of cases.6

The most common triggers of anaphylaxis vary by age. (See Table 1.) Food is the most common trigger for anaphylaxis in infants and children.6,9,14-16 When food is the trigger for anaphylaxis, the time to onset of symptoms often is five minutes to two hours, averaging 30 minutes from ingestion.17 About 50% of all anaphylaxis-related ED visits are caused by food allergens, and in 2012, the total annual direct medical cost of pediatric food allergy ED visits alone was estimated at $764 million.18,19 The rate of food-induced anaphylaxis, especially in children and teenagers, has been increasing steadily for decades.10 The incidence of food- induced anaphylaxis is highest in infants and preschool children, followed by older children and, lastly, in adults.12,15 Food is a common trigger in adolescents, but those patients start mirroring adults with other triggers becoming more common. About 40% of adolescent patients present with food triggers, 40% with envenomation triggers, and 10% with medication as a trigger.15 Meanwhile, medication and insect venom are the most common triggers in adults.2,9 The most common medication triggers are antibiotics, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), immunomodulators, and biologics.2,13,17 In many cases, a specific trigger might not be initially identified, especially in the ED.2,13

Table 1. Common Triggers for Anaphylaxis by Age2,6,7,9,13,15,17,24,35,38 |

||

| Age Group | Most Common Triggers | Other Triggers |

Infants |

|

|

Children |

|

|

Adolescents |

|

|

Adults |

|

|

Elderly (> 60 years) |

|

|

The median time between exposure and cardiorespiratory arrest can be as little as five minutes when medication is the trigger, compared to 30 minutes when food is the trigger. Some studies suggest that medication is the most common cause of pediatric fatalities in the United States, Australia, and Europe, but that foods are the most common trigger for patients younger than 30 years old in the United Kingdom. |

||

Morbidity and Mortality

Fatalities from anaphylaxis can be caused by respiratory failure and/or shock.17 Mortality caused by anaphylaxis ranges from 0.47 to 0.76 per million persons in the United States and the United Kingdom.2,9 More than 50% of fatalities happen within one hour of symptom onset.6,20 Despite the low overall fatality rate, adolescents are a high-risk population, with ages 13 to 21 years being at the highest risk for fatal food allergies.21,22 Potential contributing factors are increased risk-taking behaviors, lack of insight, and delayed treatment, including decreased possession and use of emergency treatment (epinephrine autoinjectors [EAIs]).22

Additionally, delays in diagnosis and treatment of anaphylaxis are associated with higher morbidity and mortality.2,7,9,23 This is in part because vague or nonspecific symptoms and atypical or variable presentations of anaphylaxis may contribute to delays in diagnosis and because fatal anaphylaxis may present without skin or cardiovascular manifestations.6,15,17 A U.S. study suggests that only 60% of likely anaphylactic events were recognized as anaphylaxis.24 Another study suggests that resident physicians did not recognize a presentation of anaphylaxis in close to 30% of clinical scenarios and that all levels of physicians are less likely to recognize anaphylaxis if a rash is absent.25 Therefore, a patient does not need to meet diagnostic criteria for anaphylaxis to receive the life-saving treatment of epinephrine. There is consensus that a high clinical suspicion for life-threatening allergic reaction or anaphylaxis is enough to warrant administration of intramuscular (IM) epinephrine and that there is no absolute contraindication to the use of epinephrine in anaphylaxis.2,6,8,9

Furthermore, a well-known challenge of anaphylaxis management is the underutilization and under prescription of epinephrine.6,9,23,24,26 Underutilization of epinephrine spans from patients and caregivers to Emergency Medical Services (EMS) to the ED and inpatient facilities.11,16,23,27-30 Only between 6% to 36% of children meeting criteria for anaphylaxis received epinephrine by EMS personnel and only 16% to 19% of all patients presenting with anaphylaxis received epinephrine in the ED.16,24,26,28 Additionally, patients treated for anaphylaxis in the ED received corticosteroids (74%) and antihistamine (70%) at a higher frequency than epinephrine (48%).16 Underprescription of epinephrine also is a significant disposition challenge, although it may be improving in children’s hospitals. While a large U.S. study shows that 16.2% of patients treated for anaphylaxis in the ED received a prescription for epinephrine at discharge, more recent data show that 70% of patients presenting to the ED with anaphylaxis in a large urban children’s hospital were prescribed injectable epinephrine.16,24

Even when patients have a prescription for IM epinephrine, there are significant challenges with underuse by patients and caregivers. An estimated 30% to 86% of patients at risk for severe allergic reactions are prescribed an EAI and have it available when needed.2,7 A recent study showed that 45% of participants with anaphylaxis did not use an EAI because they did not have one available, and 21% did not use one because they had no knowledge of how or when to use an EAI.27 Additionally, only 24% of participants carried at least two EAIs with them “all the time.”27

As alluded to earlier, teenagers are especially at risk for fatal anaphylaxis. In one study, more than 50% of teens intentionally ate food known to contain possible allergens.22 The same study shows that at least 38% of patients 13 to 21 years old reported not having an EAI during a severe reaction.22 Patients have expressed desire for more effective patient education during physician visits when it comes to EAIs, and patients who followed up with an allergist and immunologist were six times more apt to use EAIs.7,27

Pathophysiology

Anaphylaxis

Anaphylaxis is the most severe presentation of allergic reactions. The World Allergy Organization (WAO) 2020 guidelines point out that allergic reactions involving only the skin are a systemic manifestation of an allergic response, but in the absence of life-threatening respiratory or cardiovascular manifestations, they should not be considered anaphylaxis.6

Different mechanisms of anaphylaxis have been proposed, including immunoglobulin G (IgG) or immune complex mediated, but most suggest immunoglobulin E (IgE)-induced release of mediators from mast cells and basophils.2,9,15,31

Mediators of anaphylactic reactions include tryptase, histamine, platelet-activating factor, leukotrienes, prostaglandin, cytokines, and interleukins.9,24,31 Mast cell degranulation and the action of the previously mentioned mediators cause the symptoms seen in anaphylaxis, such as peripheral vasodilation leading to hypotension, decreased cardiac output, upper airway and mucosal edema, bronchoconstriction associated with bronchospasm, mucocutaneous manifestations, and gastrointestinal (GI) manifestations.2,6,26

Biphasic Reaction

One of the dangers of anaphylaxis is the risk of a biphasic reaction. A biphasic reaction is the recurrence of anaphylaxis within one to 72 hours after resolution of symptoms from the initial episode and without exposure to new allergens.2,9,26,32 It is critical for ED physicians to counsel families on return precautions because most biphasic reactions have been reported to happen later than the standard four- to six-hour observation period.6,26

The incidence of biphasic reaction ranges from 0.4% to 23.3% of patients presenting with anaphylaxis.1,9,32 While earlier studies suggest a prevalence of up to 20%, newer and larger studies, employing the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and Food Allergy and Anaphylaxis Network diagnostic criteria show rates closer to 0.4% to 5%.2,15,26,32 It is difficult to predict who will develop a biphasic reaction, and while clinical predictors have been proposed, there is no robust consistency across studies.26 Risk factors that have been associated with biphasic reaction include severe features or hypotension, delayed administration of epinephrine, requiring multiple doses of epinephrine, and unknown triggers.4,26,32

Refractory Anaphylaxis

Most people respond to one dose of IM epinephrine, and about 12% to 36% require a second dose of IM epinephrine.20 However, anaphylaxis that is unresponsive to two or more doses of IM epinephrine is considered to be refractory.26,29 It is estimated to happen in 3% to 5% of all anaphylaxis cases.29 It differs from a biphasic reaction in the sense that biphasic reaction has a period of resolution of symptoms, while protracted or refractory anaphylaxis does not show a symptom-free period as response to epinephrine.2,9 It is paramount to recognize this early and to quickly manage escalation of care.33 Importantly, some studies suggest a significantly higher mortality rate for refractory anaphylaxis, as much as 26%, when compared to severe cases of anaphylaxis (0.35%).29,34

Clinical Presentation of Anaphylaxis

Worldwide, there have been many proposed criteria for anaphylaxis, and it has been challenging for experts to agree on a single best definition.1 A consensus is the diagnostic criteria of anaphylaxis proposed by National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and Food Allergy and Anaphylaxis Network (NIAID/FAAN), endorsed by the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology (AAAAI); American College of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology (ACAAI); and the WAO.2,6,11 (See Table 2.)

Table 2. Diagnostic Criteria of Anaphylaxis2,11 |

|

1. 2.

|

Anaphylaxis is highly likely when one of three criteria is present. Acute onset (minutes to hours) with: Involvement of skin, mucosa, or both (e.g., generalized hives, pruritus or flushing, swollen lips, tongue, or uvula), AND:

OR At least two organ systems involved immediately following exposure to a likely trigger:

OR A drop in blood pressure as response to exposure to a potential/known trigger |

Adapted from Shaker MS, Wallace DV, Golden DBK, et al. Anaphylaxis — a 2020 practice parameter update, systematic review, and Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) analysis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2020;145:1082-1123. |

|

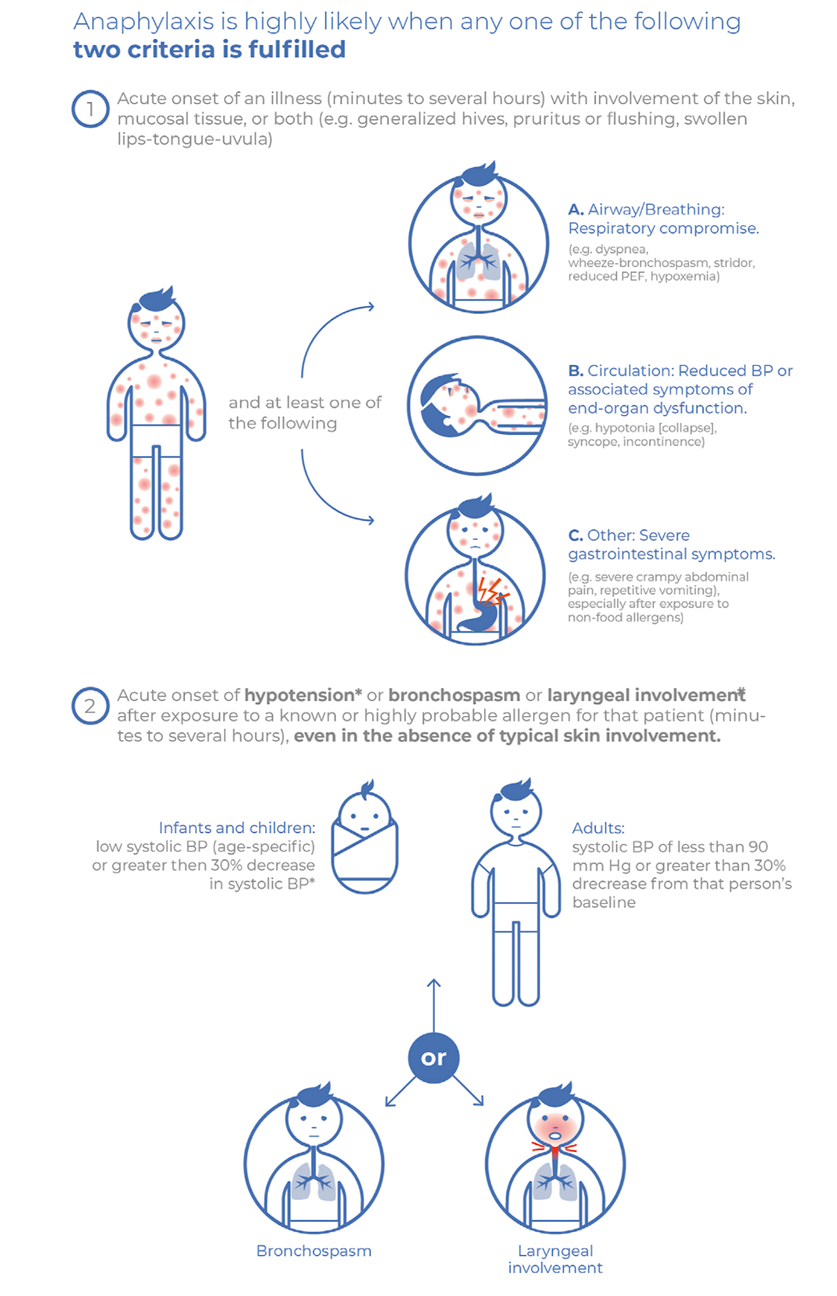

The WAO Anaphylaxis Committee proposed amendments to the definition in Table 2 to simplify and more accurately describe the criteria.6 (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2. World Allergy Organization Anaphylaxis Committee Proposed Amendments |

|

WAO: World Allergy Organization; BP: blood pressure Reprinted with permission from Cardona V, Ansotegui IJ, Ebisawa M, et al. World Allergy Organization anaphylaxis guidance 2020. World Allergy Organ J 2020;13:100472. |

Anaphylaxis presentation can be variable, not only among different people but also within the same individual during different episodes of anaphylaxis.2 It can be especially difficult to recognize anaphylaxis that presents with isolated cardiovascular symptoms, in patients without cutaneous manifestations, or in infants.1,9,14,26,35,36

The typical presentation of anaphylaxis most often includes skin and mucosa involvement (62% to 90%), followed by respiratory symptoms (45% to 70%) and gastrointestinal symptoms (25% to 45%).9 Common cutaneous manifestations include urticaria, pruritus, and angioedema. Interestingly, cutaneous manifestations may be subtle. For instance pruritus may be seen alone, without hives or urticaria. Angioedema includes swelling of eyelids, conjunctiva, lips, tongue, uvula, and oropharynx mucosa.6,9 Angioedema may be ominous, since it may be an indication of airway edema, which can lead to respiratory and cardiac arrest.

Common and sometimes life-threatening respiratory symptoms include upper airway obstruction, wheezing, stridor, and hypoxia.9 Gastrointestinal symptoms often include crampy abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, or diarrhea.2,6,9

Worrisome presentations of anaphylaxis include rapid progression (within minutes), difficulty breathing, upper airway involvement, hypotension, or shock.9 Patients who present with hypotension are at high risk for circulatory collapse.26 It is important to note that about 10% of patients may present in shock but lack the cutaneous findings, which can contribute to delayed diagnosis of anaphylaxis and mortality.9,36

For emergency medicine providers, anaphylaxis should be thought of as an acute, systemic, rapidly progressing, potentially fatal allergic reaction. If there is a high clinical suspicion for it, regardless of specific criteria, life-saving IM epinephrine should be given.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for allergic reactions includes anaphylaxis, urticarial allergic reaction (limited to skin mucosa), localized angioedema, mastocytosis and mast cell activation syndrome, hyper IgE urticaria, vasovagal reactions, capillary leak syndrome, erythema multiforme, asthma, ingestion, pheochromocytoma, and monosodium glutamate toxicity, among others.9,29,37

Emergency Approach to Anaphylaxis Management

Patients suspected to have anaphylaxis should be triaged, placed on monitors, and evaluated by a physician immediately, given the risk of rapid progression to cardiovascular instability and collapse.26

Triage should include the removal of a potential trigger; administration of IM epinephrine; assessment of airway, breathing, and circulation; assessment of skin and mental status; and positioning the patient.6,9 Most patients should be placed supine, although patients in respiratory distress may benefit from sitting.38 Pregnant patients should be semi-recumbent on the left, and children should be in a position of comfort.6,9,15 Do not suddenly sit or stand patients with anaphylaxis.26,38 Changes in position should be gradual and with attention to fluid shifts. Standing or quickly sitting has been associated with cardiovascular arrest.26,29,30 Prepare life-sustaining equipment, such as code cart and defibrillator, and be prepared to give advanced cardiac life support with continuous cardiac compressions if needed.6,26

This review emphasizes that IM epinephrine is the single most important first-line intervention for anaphylaxis. The following section will discuss specifics of epinephrine as the first-line treatment and noteworthy peculiarities and controversies of adjunct therapies.

Epinephrine

Epinephrine is an adrenergic agonist. It reverses bronchoconstriction and mucosal edema, increases systemic vascular resistance, increases cardiac output (inotropy and chronotropy), and stabilizes mast cells and basophils (inflammatory mediators).2,26 Every organ system affected by anaphylaxis has adrenergic receptors, which epinephrine acts upon.2 Therefore, the benefits of early, rapid, and consistent IM epinephrine administration when there is high suspicion for anaphylaxis cannot be overemphasized.

There is international consensus that IM epinephrine is the most effective treatment for anaphylaxis, and it is universally recommended as the first-line treatment for uniphasic and biphasic anaphylaxis. Immediate administration of IM epinephrine to the anterolateral thigh as soon as anaphylaxis is recognized or suspected is encouraged, including before arrival to emergency care.9,11,20,25 Guidelines recommend treatment with epinephrine if there is high clinical suspicion for anaphylaxis, regardless of specific criteria discussed previously. The effect of IM epinephrine peak at 10 minutes.20 Early administration of epinephrine is associated with prevention of respiratory failure and cardiovascular collapse.36 Conversely, delay in epinephrine administration is associated with higher morbidity and mortality.6,7,23 See Table 3 for weight-based dosing for IM epinephrine. It is important not to administer IM epinephrine to the buttock or stomach. IM Epinephrine administered in the buttock has been associated with severe Clostridium infection and gas gangrene.29,30

Table 3. Dosing for IM Epinephrine in the Treatment of Anaphylaxis2,6,9,20,26,29,38 |

|||

| Weight* | IM Dosing | Max Weight-Based Dosing** | EAI Dosing*** |

< 7.5 kg |

Draw up 0.01 mg/kg (0.01 mL/kg of epinephrine 1 mg/mL) |

0.075 mg per single dose |

Be mindful of the controversy surrounding EAI dosing in this weight class. |

7.5 kg to < 15 kg |

Draw up 0.01 mg/kg (0.01 mL/kg of epinephrine 1mg/mL) |

0.15 mg per single dose |

0.10 mg autoinjector |

15 kg to < 30 kg |

Draw up 0.01 mg/kg (0.01 mL/kg of epinephrine 1mg/mL) |

0.30 mg per single dose |

0.15 mg autoinjector |

30 kg to < 50 kg |

Draw up 0.3 mL of epinephrine 1 mg/mL |

0.50 mg per single dose |

0.30 mg autoinjector |

> 18 years old or ≥ 50 kg |

Draw up 0.3 mL to 0.5 mL of epinephrine 1 mg/mL |

0.50 mg per single dose |

0.30 mg autoinjector |

IM: intramuscular; EAI: epinephrine autoinjector *In individuals weighing more than 100 kg, consider administering IM epinephrine by needle and syringe (instead of autoinjector). Data suggest that the length of autoinjector needles is not long enough for appropriate epinephrine delivery. **Doses can be repeated every five to 15 minutes up to three times. ***If using autoinjector, hold in place for three seconds to ensure medication delivery. |

|||

There is controversy in the use of 0.10 mg autoinjectors (the smallest dose available at the time of this publication) in infants weighing less than 7.5 kg because the dose would be higher than the recommended dose based on weight.14,39 However, some protocols, including some rapid responders, may use fixed dosing (i.e., 0.10 mg) for patients less than 7.5 kg, given the potential risks of error during medication preparation.40 Errors in medication preparation may include delay in dosing, incorrect dosing, complete lack of drawing up epinephrine in the prepared dose, or even epinephrine degradation, and are particularly challenging for caregivers and non-medical personnel.39,40

Additionally, side effects of IM epinephrine are similar to symptoms caused by endogenous epinephrine surge, “fight or flight,” and significant negative side effects are rare in children.39

Based on the evidence, there have been no adverse effects reported from using a higher dose in infants weighing less than 7.5 kg. Therefore, many experts and physicians recommend, and it is reasonable to consider the administration of, a 0.10 mg autoinjector for infants weighing less than 7.5 kg, given the favorable benefit-to-risk profile in the emergent treatment of anaphylaxis and the potential risks of medication preparation.38-41

Intravenous (IV) epinephrine is not a first-line treatment. Consider it in patients who, despite two or more doses of IM epinephrine, continue to be hypotensive, have signs of cardiovascular collapse, or have ongoing respiratory symptoms.2,6,11,20,26,30 Reserve IV epinephrine for special situations. Administer it with extreme caution, when risks and benefits have been assessed, and when there is confirmation that the correct dose is being given while the patients are being monitored by experienced personnel.6,11,26

While it is important that these cases are monitored in a hospital setting given the risks, including arrhythmias and myocardial infarctions, adverse events associated with IV epinephrine are rare and associated with its incorrect use (wrong doses or concentrations).2,7,20,26,30 Consider glucagon for patients not responding to epinephrine, especially those on beta-blockers, despite limited evidence.6,9,26,30

Adjunct therapy still is administered more frequently than epinephrine; however, the trend has improved in the past few years.4,7 The use of adjunct therapy should be individualized based on patients’ symptoms.4 See Table 4 for a summary of symptomatic treatment following IM epinephrine.

Table 4. Adjunct Therapies for Anaphylaxis Management and Symptomatic Treatment2,15,26,38 |

||

| Therapy | When to Consider | Notes |

Oxygen supplementation |

|

|

Advanced airway |

|

|

Bronchodilators (beta-2-agonist, less commonly anticholinergics) |

|

|

Fluids |

|

|

Antihistamine (H1 and H2 blockers) |

|

|

Glucocorticoids |

|

|

IV epinephrine |

|

|

IM: intramuscular; BP: blood pressure; GI: gastrointestinal; IV: intravenous |

||

Oxygen Supplementation

Provide oxygen supplementation, preferably at 100% using a nonrebreather, for all patients in respiratory distress or with refractory anaphylaxis.6,9,38

Advanced Airway

Angioedema is a critical sign of airway involvement, which may lead to respiratory failure, and is a risk factor for requiring intubation.29 Despite the risk, large studies show that only 0.2% of pediatric patients and 1.5% of adults admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) for anaphylaxis required intubation.4,29 While the rate of endotracheal intubation in anaphylaxis is low, it is crucial to assess the airway and be prepared to intubate, since anaphylaxis can progress rapidly. An experienced provider should manage the airway in an anaphylaxis patient, and appropriate backup should be available.26

Bronchodilators

Bronchodilators, such as beta-2 agonists, are used to treat anaphylaxis-related bronchospasm and lower airway obstruction (wheezing).2,6,29,38 However, there are no strong data to support this practice.26 If given, bronchodilators can be repeated every 15 minutes.9 Inhaled anticholinergics (such as ipratropium) are used less frequently but also can be considered.26 If there is upper airway obstruction, consider nebulized epinephrine.6 Note that, if patients have ongoing respiratory distress, the previously mentioned treatments are second-line after administering repeated doses of epinephrine.6

Fluids

Hypotension in anaphylaxis is caused by distributive or vasodilatory shock. Thoughtful but aggressive fluid resuscitation is an indispensable supportive treatment.29 Patients may require large volumes of fluid resuscitation because of capillary leak losses (which can happen in minutes) in addition to vomiting and diarrhea.26 Establish peripheral IV access with large-bore catheters.6 Bolus 20 mL/kg of isotonic fluids for children and 1-2 L of crystalloid for children weighing more than 50 kg or for adults, given no history of congestive heart failure or end-stage renal disease.26 Repeat bolus as needed to maintain perfusion.26

Be cautious with patients who are not in shock and can maintain perfusion but are experiencing respiratory symptoms, since aggressive fluid resuscitation may lead to fluid overload and worsen their respiratory symptoms.26 The advent of point-of-care ultrasound of lungs and inferior vena cava can help guide fluid status and the need for fluid resuscitation.26 If peripheral or quick central access cannot be established, use intraosseous access.9,20,29

Antihistamines

Antihistamines have a slow onset of action and do not stabilize or prevent mast cell degranulation. They also do not reverse hypotension, bronchospasm, or oropharyngeal or laryngeal edema. 2,6,9,15,20,26,29 Therefore, they are second-line treatment for anaphylaxis and should not delay IM epinephrine administration.2,9 While H1 and H2 blockers often are given when treating anaphylaxis, there are no data to support their efficacy in anaphylaxis outcomes, especially H2 blockers.2,9,20,26

However, antihistamines are effective in relieving cutaneous symptoms, such as urticaria, flushing and pruritus, rhinorrhea, and histamine-sensitive angioedema.2,6,26,29 Therefore, it is reasonable to provide antihistamines for comfort.2,15,29 Antihistamines are also reasonable as adjunct therapy for GI manifestations.26 If administered, oral second-generation H1 antihistamines are the treatment of choice in patients who can take oral medication. Second-generation H1 antihistamines are long-acting and less sedating than first generation H1 antihistamines.15

Beware of the side effects of antihistamines in the treatment of anaphylaxis, such as sedation or hypotension.6 If giving an IV antihistamine, administer it slowly, since it can worsen shock and cardiac output.29

Glucocorticoids

Glucocorticoid use is an area ripe with controversy and variation in practice. Controversies range from dosing, timing of administration, effectiveness, and risk-benefit profile.

Routine use of glucocorticoids is becoming increasingly controversial.6 Where once there was a lack of evidence to support clinical benefit of glucocorticoids in the acute management of anaphylaxis, there now is growing evidence that they do not provide benefit in the acute management of anaphylaxis, and they even may be harmful, especially in children.1,2,6,9,20,23,30,31,42 This is, at least in part, because glucocorticoids have a slow onset of action, taking four to six hours to inhibit gene expression and the production of additional inflammatory mediators.2,20 Recent data have shown adverse effects in children even after a single burst of steroids.42 Many studies suggest glucocorticoids are no longer recommended for the acute treatment of anaphylaxis or recommend against their use given potential harms.2,15,23,26 This may be in line with the decline in the use of systemic steroids for treatment of anaphylaxis from 2016 to 2022.4 Additionally, ED physicians discharged patients treated for anaphylaxis with scheduled steroids more often than allergy specialists did.15

Challenges to limiting glucocorticoid use in the acute management of anaphylaxis include perceived benefit, safety profile, cost, and clinician comfort in using them.4 It is reasonable that, without robust evidence (likely randomized controlled trials with convincing data to decrease the use of glucocorticoids), it will be difficult to reduce their use in practice.4 However, this is something to consider as new data emerge.

Glucocorticoids may be associated with decreased length of stay in the hospital but have not been shown to decrease return ED visits after discharge.2 If administered, do not use steroids in place of or before epinephrine.2

Diagnostic Studies

There is consensus that anaphylaxis is a clinical diagnosis and that, on the rare occasion that a patient requires a workup, it must not delay diagnosis and treatment. Tryptase levels can assist in confirming the diagnosis of anaphylaxis and the evaluation of other anaphylactoid reactions, including mast-cell degranulation syndrome.2,6,15,38 Of note, about 40% of children will not have elevated tryptase levels, and tryptase may not be elevated in food-induced anaphylaxis, which is the most common cause of anaphylaxis for children.15,38

Disposition and ED Discharge

Observation Period

The exact observation period for patients presenting in anaphylaxis is another area of uncertainty. There is consensus that all patients should be observed at least until showing significant symptom improvement, if not resolution. However, recommendations range from one to eight hours of direct observation and monitoring, or admission, pending patient presentation, anaphylaxis severity, and risk of biphasic reaction, among other factors.2,6,9,15 Therefore, the length of observation after improvement or resolution of symptoms should be individualized, taking into account patient-specific characteristics.2,6,15

While there is no current consensus, a four-hour observation period generally is accepted. There needs to be a balance between discharge prior to resolution of symptoms and prolonged stays that may not be cost-effective or timely for patients. For instance, low-risk patients may only need to be observed for shorter periods while patients presenting in severe anaphylaxis, younger and nonverbal children, or those with unknown triggers may require longer observation periods.2,6,15

One meta-analysis suggests that, when low-risk patients were observed for one hour after resolution of symptoms, secondary reaction was excluded in greater than 95% of patients.15 Conversely, a cost-effective analysis suggests that a high-risk patient should be observed for at least five hours while asymptomatic.2 The decision about ideal observation period also is contingent on appropriate establishment of anaphylaxis education for patients and families and access to care and follow-up.6,15

Admission

In the United States, less than 20% of ED presentations for anaphylaxis required admission.1 Patients who are hemodynamically stable but have mild symptoms (cutaneous, GI) may be admitted for observation.26 Additionally, consider admission for high-risk patients and for stable patients with a history of severe, delayed, or biphasic anaphylactic reaction.2,15 Admit to an ICU patients who have ongoing symptoms or who require epinephrine infusion or intubation.26

Discharge

It is crucial that every patient in the United States who has been treated for anaphylaxis leaves the ED with an active prescription for epinephrine. The aim is for 100% of patients who receive a diagnosis of or are treated for anaphylaxis to leave the ED with a new or active prescription for IM epinephrine.

Prescribe a minimum of two kits, each with two EAIs, to every patient. It is important not to split up the EAIs within a kit because 7% to 30% of patients require a second dose of epinephrine.9,18

Despite having the medication, patients with anaphylaxis recurrence underuse EAI.6,7,40 Reasons for underuse include lack of recognition of anaphylaxis, not knowing indications to use an EAI, not having an EAI available, lack of comfort using an EAI, not thinking it was necessary, and fear of using it.7,27,40 Therefore, it is the responsibility of ED personnel to counsel patients and families on the appropriate use of IM epinephrine prior to discharge from the ED, especially given decreasing rates of admission.

Of note, as much as 25% of food allergy reactions that happen in school are in children with no known food allergy.7 Legislation in the United States allows for voluntary stocking and use of EAIs in schools, but only a few mandate their use.7 On discharge, consider recommending that one kit be stored at school, given the significant time children spend at school.

Epinephrine Without Autoinjectors

For cases where EAI either is not affordable or available, physicians must discuss alternative methods to administer epinephrine.7,38,40 More work is currently underway to address barriers to epinephrine administration outside of medical facilities. Alternative ways to administer epinephrine are under investigation and are further described in the following sections.8

Education

A significant gap in care is patient and caregiver education for the use of IM epinephrine. ED personnel are in a prime position to empower caregivers and patients and minimize subsequent presentations due to anaphylaxis, so discharge education is extremely important.

Caregivers for children with food allergies may not have self-injectable epinephrine nor be able to administer it appropriately when asked to demonstrate its use.15,21 Therefore, appropriate and effective teaching on IM epinephrine administration and even demonstration (with trainers) is fundamental prior to discharge from the ED.

Action Plan

Teach an individualized written emergency action plan to all patients and their families at risk for anaphylaxis.16,40 Include signs and symptoms of anaphylaxis, instructions for EAI administration, and emergency contact information.6,9,21,38 This can be found at www.aaaai.org. It is important to have families “teach back” and practice application for review of ED personnel in a controlled environment because performing these steps in a stressful situation would be even more challenging.

Follow-Up

Consensus and WAO guidelines recommend periodic follow-up with allergists or immunologists to review recurrence prevention, individualized action plan revisions, epinephrine self-administration use, and controlling comorbidities, since this is a chronic medical problem.6,9 Refer all patients presenting for or with suspicion for anaphylaxis to an allergist or immunologist.2,6,9,15,17 Despite data that a referral to a specialist improved clinical outcomes and reduced hospital admissions, less than half of patients were given a referral to an allergy specialist after diagnosis or treatment for anaphylaxis.9,16,17 Additionally, long-term management of risk factors for fatal anaphylaxis, such as poorly controlled asthma or cardiovascular disease and risk-taking behavior, is important to minimize recurrence.6

Referral to specialists is especially important because less than half of patients might know their trigger on initial presentation, and suspected triggers often were not confirmed at the time of allergy testing.2,38 Specialists will consider the role of testing and immunotherapy. Skin prick testing and allergen-specific serum IgE levels can be helpful in determining suspected triggers.9 Common causes of anaphylaxis vary by age group and geographic location; therefore, outpatient allergy testing should be tailored to patient history and data on common causes of anaphylaxis in a particular region.6 Nonspecific allergen panels are not recommended because they can have false positives and may lead to unnecessary avoidance of allergens.9 For patients with food allergies and multiple potential restrictions, consider a referral to a nutritionist and to a psychologist, as appropriate.6,9

Future Directions

It is important to continue to grow and improve the life-saving management providers offer in the ED. The following are some exciting data and developments in the pipeline for the treatment of anaphylaxis in the ED.

ED protocols might improve compliance. Patients were more likely to receive epinephrine after an order set was implemented.7,26 Providers should consider implementing an order set for anaphylaxis in the ED if one is not already in place. Multiple alternative routes for epinephrine administration are under investigation. Alternative routes include sublingual (rapidly disintegrating tablets), intranasal, inhaled, and needle-free IM administration.2,6,8,15 At the time of this publication, these had not yet been approved for clinical use. Additionally, there have been multiple randomized controlled trials in the realm of desensitization therapy to prevent anaphylaxis that achieved desensitization by oral or sublingual immunotherapy.9 At the time of this publication, these had not yet been approved for clinical use.

A global population database with accurate information on anaphylaxis, including diverse and broad populations, is needed to improve the quality of data on surveillance, trends, and the development of interventions and their effectiveness. Furthermore, the diagnosis and management of anaphylaxis worldwide requires evaluation with consideration for access to care and long-term treatment with the goal of facilitating cost-effective, sustainable anaphylaxis management that is socioeconomically conscious and involves community and public health strategies.10

Conclusion

Anaphylaxis is an acute, systemic, potentially life-threatening allergic reaction. It can affect airway, breathing, and circulation and is a medical emergency. Anaphylaxis is a clinical diagnosis, which ED providers should feel comfortable recognizing and treating.

While there are consensus criteria for the diagnosis of anaphylaxis, do not delay administration of life-saving IM epinephrine if there is a high clinical suspicion for anaphylaxis. Additionally, adjuvant therapy should never delay the administration of IM epinephrine. The recommended observation times vary, but they should be tailored to patients’ age, severity of presentation, and risk factors.

It is paramount that IM epinephrine is prescribed and that patients and families carry epinephrine with them. Morbidity and mortality in anaphylaxis are associated with the underuse of epinephrine both by patients and healthcare providers alike. ED or inpatient personnel should provide patients with a written action plan and ensure their ability to recognize anaphylaxis and administer epinephrine prior to discharge. Appropriate long-term follow up with allergy and immunology specialists is indispensable and associated with better clinical outcomes and reduced admission rates. As emergency medicine physicians, we are in a position to decrease anaphylaxis-related fatalities, minimize recurrence, and significantly increase the quality of life of patients and their families beyond their presentation to the ED. See Table 5 for a summary of what has been reviewed.

Table 5. Pearls and Pitfalls of Anaphylaxis Management |

Pearls

Pitfalls

|

Adapted from Amieva-Wang NE, Shandro J, Sohoni A, Fassl B. A Practical Guide to Pediatric Emergency Medicine. Caring for Children in the Emergency Department. Cambridge University Press;2011:56. |

Acknowledgement

Our deepest appreciation to Jeff Moss, PharmD, BCCCP, for his invaluable collaboration, insight, and revision of Table 3 and associated footnotes and references.

References

To view the references online, visit https://bit.ly/3OMrTdn.

The incidence of anaphylaxis, a rapidly progressive and potentially fatal disease, is increasing and unfortunately common in children. It is imperative that all acute care providers are prepared to recognize, quickly treat, and ensure appropriate follow-up for these patients. The authors focus on anaphylaxis, its presentation, management, and disposition from the ED.

Subscribe Now for Access

You have reached your article limit for the month. We hope you found our articles both enjoyable and insightful. For information on new subscriptions, product trials, alternative billing arrangements or group and site discounts please call 800-688-2421. We look forward to having you as a long-term member of the Relias Media community.