Intimate Partner Violence

May 1, 2023

Related Articles

-

Echocardiographic Estimation of Left Atrial Pressure in Atrial Fibrillation Patients

-

Philadelphia Jury Awards $6.8M After Hospital Fails to Find Stomach Perforation

-

Pennsylvania Court Affirms $8 Million Verdict for Failure To Repair Uterine Artery

-

Older Physicians May Need Attention to Ensure Patient Safety

-

Documentation Huddles Improve Quality and Safety

AUTHORS

Brian L. Springer, MD, FACEP, Director, Division of Tactical Emergency Medicine, Wright State University Department of Emergency Medicine, Dayton, OH

Jared Brown, MD, Emergency Medicine, JB Andrews, MD

PEER REVIEWER

Ralph Riviello, MD, MS, FACEP, Professor and Chair, Department of Emergency Medicine, University of Texas San Antonio

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

- Unfortunately, many victims are misdiagnosed with non-intimate partner violence (IPV) etiologies. The reasons for this are multifactorial, and include conflicting or inadequate information in the patient’s history, failure to adequately screen for partner violence, and a tendency to underestimate the extent of IPV among patients.

- IPV is just as prevalent, if not more prevalent, in male and female same-sex couples. Men may be victimized by their female partners and have increased risk of developing mental and physical health sequelae of abuse.

- Nonfatal strangulation, as opposed to other forms of physical violence, such as being punched or struck with an object, has been associated with risk of future attempted or completed homicide.

- Most states have enacted mandatory reporting laws for certain types of nonaccidental trauma. These laws differ from mandatory reporting laws involving suspected child abuse or elder abuse in that they do not target any one vulnerable group. The specifics of the laws differ from state to state, but the broad categories can be defined as: those that require reporting of injuries caused by weapons; those that require reporting injuries caused in violation of criminal laws, as a result of violence, or through nonaccidental means; and those that require reporting specifically of domestic violence cases.

- Although studies suggest that universal screening leads to higher detection rates, the available research has been unable to demonstrate that this ultimately improves patient care or allows for more effective handling of domestic violence cases.

- Intimate partner violence often has characteristic injury patterns, with head, neck, and facial injuries being the most common. In fact, women with these injury patterns are 7.5 to 11.8 times more likely to report domestic violence as the cause for their injury than women with injuries isolated to other body parts.

Domestic violence and abuse is a national and global healthcare problem with massive consequences, affecting men, women, and children, which worsened during the COVID-19 pandemic. Awareness, recognition, and resource allocation, in addition to trauma management, is an important aspect of emergent care of the trauma patient possibly injured in a domestic violence incident.

— Ann M. Dietrich, MD, Editor

Introduction and Background

Intimate partner violence (IPV) can be defined as a behavior pattern committed by a person’s current or former spouse, common-law partner, sexual partner, or dating partner.1 The behavior can include physical and sexual assault, psychological abuse, forced social isolation, intimidation, threats, and stalking.2 The reported incidence varies greatly, depending on how IPV is measured. In the United States, IPV affects between 2.7% and 13.9% of women and between 2.0% and 18.1% of men annually.3 More than one-third of women and one-fourth of men will experience physical violence, threats, and sexual assault by a partner in their lifetime. The lifetime prevalence of IPV in Western and European populations ranges from 26% to 74%.1-3 Within primary care and emergency healthcare settings, the reported prevalence of IPV survivors is anywhere from 12% to 45%.3 Rates of reported IPV increased during the COVID-19 pandemic. Quarantines, social isolation, travel restrictions, and stay-at-home orders instituted to curb the spread of disease have had profound social, financial, and psychological repercussions globally.4 This resulted in a “shadow pandemic” of IPV that affected countries with both weak and strong economies.5

IPV results in injury for up to 15% of women and 4% of men. Half of these will require medical care for acute injuries. Often, the emergency department (ED) is the first point of contact IPV victims will have with the healthcare system. This has helped change the perception of IPV as a social and criminal concern that could be addressed exclusively through public policy and law enforcement to the current understanding of abuse as a major healthcare problem. Emergency physicians, trauma physicians, and other primary care health providers are in a unique position to be able to identify victims of IPV and to refer them to appropriate services. Unfortunately, many victims who present to the ED ultimately are misdiagnosed with non-IPV etiologies.1 The reasons for this are multifactorial, and include conflicting or inadequate information in the patient’s history, as well as a failure to adequately screen for partner violence. Healthcare providers who regularly have contact with victims of violence have a tendency to underestimate the extent of IPV among their patients. In ED and inpatient settings, patients initially present seeking care for complaints unrelated to violence and then return for treatment of IPV-related injuries at a later date. Women murdered by an intimate partner are likely to have been seen in an ED in the two years prior to their deaths, with the majority having at least one previous injury-related visit.1,6

When looking at victims of IPV and their contact with the criminal justice system, similar findings are seen. A cohort of almost 1,000 IPV victims generated more than 3,000 police calls and more than 5,000 ED visits over a four-year study period.7 Seventy-nine percent of the cohort had one or more ED visits following their initial IPV assault, with the mean number of ED visits being 7.17 (vs. a mean of 3.61 non-IPV police incidents) over four years. ED users tended to be unmarried, did not have children, and were more likely to be uninsured or covered by Medicaid. ED users had greater numbers of IPV-related police calls and more severe injuries. Even in patients presenting within one day of an IPV-related police call, the majority of ED visits (78.4%) were for medical complaints, not assault. Mental health and substance abuse complaints (“crisis,” “suicidal,” “overdose,” etc.) had higher rates of IPV association than complaints related to injury.

When looking retrospectively at the National Trauma Data Bank from 2007-2012, domestic violence tends to be underdiagnosed when compared to estimates of prevalence. Although this may be due in part to variability in the criteria used to define domestic violence among the hospitals from which data were derived, overall the findings support that underdiagnosis is common.8 Out of almost 17,000 patients identified, the study found that Blacks and Hispanics were more likely to experience domestic violence than other traumatic events, while whites experienced domestic violence less compared to other mechanisms of trauma. Male relatives were the most common perpetrators (38%), followed by female and other relatives (19%). Compared to victims of other traumatic events, victims of domestic violence tended to be younger (mean age 16 years) and more often female. There was a linear increase in the reported incidence of domestic violence during the study period. The overall mortality rate was 5.9%, with children at the greatest risk for death. Even when controlling for age, there was no difference in mortality between male and female patients.

It is fallacious to think that the prevalence of IPV, as well as its links to drinking and illicit substance abuse, is an urban, inner-city phenomenon. A 2014 retrospective, cross-sectional study of women admitted to a rural Level I trauma center found that both past-year and lifetime experience of IPV was associated with self-reported illicit substance abuse and alcohol abuse. Diagnosed mental illness, such as major depression, suicidal ideation, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and generalized anxiety disorder, were higher in both IPV groups than in the general population.9

Adolescents, and particularly adolescent females, are at high risk for IPV, and there is a paucity of data both nationally and internationally on prevalence and risk factors.10,11 A study screening adolescent female patients for IPV in a Midwest urban ED found that one in three experienced dating violence. Risky behaviors linked to a positive IPV screen included alcohol use, fighting in school, and a history of a sexually transmitted infection. Exposure to violence at home also was linked to IPV risk, with 36.6% reporting physical parental arguments and 78.8% reporting being subjected to corporal punishment.10 Internationally, use of alcohol and witnessing IPV at home were identified as significant risk factors for young and adolescent women. Children may model the behavior of their parents and may see that violent behavior is unpunished and an effective strategy to gain authority. Along with a lack of knowledge about nonviolent coping strategies, this may result in violent behavior later.11

As noted, alcohol use and abuse are associated with IPV risk among both victims and perpetrators. Binge-drinking rates are high among both abusers as well as those who react to IPV with violence themselves.12 Drug use, including crack, cocaine, and heroin, also is more common among ED users involved in IPV. These drugs have been linked to an increased likelihood of injurious IPV, possibly due to increasing paranoia, jealousy, and irritability in both partners, as well as distorted perceptions and impaired judgment and ability to recognize early warning signs of potential violence.13 One study noted that IPV victims and perpetrators double their risk of using hard drugs, as drug use may be a risk factor and consequence of IPV.12 Looking specifically at a cross-sectional study of white, Black, and Hispanic males 18-49 years of age who are cohabiting with a spouse or partner, Black and Hispanic men were disproportionately represented among perpetrators of IPV. Perpetrators also were younger, were not currently married to their cohabiting partner, had lower income or were unemployed, and had no or government-subsidized health insurance. Heavy drinking and binge drinking, illicit drug use, and drug or alcohol dependence all were associated with IPV.14 Among adult male and female patients discharged from the ED, IPV is positively associated with specific mental health diagnoses, including alcohol-related problems, adjustment disorders, intentional self-harm and self-inflicted injury, anxiety disorders, and mood disorders. Women tend to report more symptoms related to depression, PTSD, and drug and alcohol use, whereas men tend to report symptoms related to PTSD, depression, and suicidality. Interestingly, there is an inverse relationship between IPV and schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders. This may be a result of underreporting or may be secondary to a lack of a partner among patients who present to the ED with these diagnoses.15

Providers often assume that women in heterosexual relationships are the only ones experiencing IPV, with men being the primary perpetrators. However, IPV is just as prevalent, if not more prevalent, in male and female same-sex couples. Men also may be victimized by their female partners and have an increased risk of developing mental and physical health sequelae of abuse.3 Compared to other sexual minority men and women, transgender people have comparable prevalence of IPV, and significantly higher prevalence than cisgender people.16 Injury severity also crosses all boundaries: The victim profile as well as the injuries seen are heterogeneous. Injuries with high Injury Severity Scores correlating with life-threatening injuries occur in both men and women and across all age groups, including the elderly.17 If the examiner focuses only on identifying facial and upper extremity wounds on young female patients as indicators of IPV, they are likely to fail to identify many cases. Although older and younger victims experience IPV at similar rates, the health risks associated with IPV increase as victims age, with studies demonstrating increased health problems for older individuals who experience IPV.18 Healthcare providers need to be aware of this increased morbidity/mortality risk in older victims and allocate proper resources to provide assistance.

Physical abuse results in findings that can be relatively easy to recognize and assess, especially if the victim is forthright about being abused. Bruises, lacerations, fractures, and other injuries from physical and sexual assault can be documented and treated by emergency providers; law enforcement and sexual assault nurse examiners (SANE) can document and photograph these findings further and enter them as evidence into the criminal justice system. Patterned injuries may provide further forensic evidence of abuse. Patterned injuries have a distinct appearance that may reproduce the characteristics of the object causing the injury. Examples include a bruise or abrasion in the shape of a hand or other object, or a stab wound with a distinct pattern of a tool such as a Phillips head screwdriver.19

Unfortunately, many victims will not reveal how they sustained their injuries out of fear and because of the intensive psychological abuse and manipulation that often precedes physical abuse. When a victim decides to leave an abusive relationship, the abuser may experience humiliation and a perceived lack of control and power, which may precipitate homicidal behavior.18 Estimates are that more than 1,800 people in the United States are murdered by their partners every year, with the vast majority being women (85%). In fact, intimate partner homicide accounts for almost half of the female homicides committed in the United States annually. In situations of IPV, the presence of a firearm increases the risk of homicide five-fold, and 50% of intimate partner homicides are committed with firearms.20

Another risk factor for intimate partner homicide is the presence of children at home; in fact, children are the most frequent additional victims of intimate partner homicide. Pregnancy also may be a risk factor, although the literature is mixed with respect to reported rates of IPV and homicide among pregnant women and women in the postpartum period. Spouses actually pose a lower lethality risk than dating partners and ex-partners. This association may relate to the aforementioned risk of escalation of violence when a victim leaves, and it requires further study.18 Of note, nonfatal strangulation, as opposed to other forms of physical violence such as being punched or struck with an object, has been associated with a substantial risk of future attempted or completed homicide.21

Barriers to Leaving

“Why doesn’t she leave?” is a question commonly asked by health providers who care for severely abused women. The problem with this question is fairly obvious on reflection: It holds the victim accountable for the actions of the abuser. It has been posited that the more appropriate questions would be to ask why does the perpetrator abuse, why doesn’t the perpetrator leave the home, or why is the woman expected to leave her home, which questions the inherent belief in a man’s entitlement to his home based on a long history of viewing a man’s rights over his wife’s in terms of income, property ownership, and children.22 The question that is the most useful and best acknowledges the reality of the situation for those of any age or gender experiencing IPV is “What are the barriers to leaving?”23 When contemplating their own abusive relationship, victims of IPV communicate barriers to leaving that are similar. Although men tend to identify more stereotypical masculine identity reasons for remaining with a partner (personal strength, fatherhood, a desire to protect others), both men and women largely converged on their answers.24 These reasons include hope for the future, positive emotions toward/excuses for one’s partner, lack of practical and familial resources, parenting and religious concerns, views of abuse as normative, and feelings of fear and shame.24 When looking at these reasons individually, one sees a significant degree of overlap and connectivity. (See Table 1.)

Table 1. Barriers to Leaving a Violent Relationship |

|

Hope for the Future: The victim believes that things will change and that the abuser is really a good person who eventually will show love.24 The victim often fantasizes that he or she can “fix” the abuser by working harder to make their life less stressful and improve their relationship. When the abuser says he or she is sorry for hurting the victim, the victim believes the abuser. When the relationship began, the victim saw a caring and loving side to the partner, which the victim believes will come back.23

Positive Emotions/Excuses: The victim loves and relies on the abuser. He or she is willing to excuse the abuser’s behavior as a result of some extenuating circumstance or stressor, such as problems with drugs, alcohol, work, finances, or children.23,24

Lack of Practical/Familial Resources: Victims have very genuine fears of the financial repercussions of leaving the relationship. The victims fear losing their families, their children, and their homes. In many cases, the abusers have maintained control of finances, leaving the victims with limited access to money.23,24 Victims also may not be aware of resources available to assist them or may not trust those resources. Many victims of IPV relate their own mental health concerns or concerns about their children’s behaviors to healthcare professionals, who often fail to make the connection to abuse.25 IPV victims benefit from moral support and understanding of friends and family, but may be isolated geographically from those resources or may be estranged from them after returning to an abusive partner.23,25

Parenting and Religious Concerns: Victims worry that if they leave an abusive relationship, they will lose their children. Alternately, they may feel that their children benefit from a two-parent household and do not want to take that away from them.23,24 Victims often are conflicted about seeking help because of the effect of uprooting their children and financial concerns about providing for them. While they wish to protect their children from IPV, they also wish to protect them from having to interact with law enforcement and the court system.26 Alternately, many victims finally take action when they feel their children are being affected negatively by violence or are at direct risk of violence themselves. Someone else being at risk often is a turning point in abusive relationships that prompts victims to initiate the process of leaving.26,27

Victims may have been raised in a religion that teaches that marriage is for life. They feel that their vows require them to stay and that they must not break that promise.23,24 The ability of clergy to intervene effectively in IPV remains vastly understudied, and victims’ satisfaction with clerical support in reported abuse is mixed. In one study of services available for victims, researchers found only three that were used often and found to be helpful: welfare benefits, food banks, and religious or spiritual counseling.28 Alternately, women may be confronted by traditional notions that they are to blame for problems in the relationship.29 Further study is needed of how religious and spiritual services can help IPV victims, and how spirituality can be incorporated into available services without trying to influence the victim’s values and beliefs.28

Abuse as Normative: Victims brought up in a home in which abuse was present think that violence is part of normal relationships. They may have witnessed parents fighting or a parent, sibling, or other relative being beaten.23,24 Cultural and social norms may support different types of violence. Traditional beliefs that men have a right to control or discipline women through physical measures can make women susceptible to violence by their intimate partners. Cultural stigmatization of sexual violence may keep victims from seeking help. Cultural and social norms about alcohol may encourage its use with resultant risk for violent acts.30

Feelings of Fear and Shame: Abusers may threaten to harm or kill their partner, their children, or their partner’s family if they leave. Victims know that if they attempt to leave, their partner will search until they find them. Victims often feel ashamed and blame themselves for causing the abuse. They feel that once others know about the abuse, they will reject them or disapprove of their behavior, as if they are to blame. Cultural norms mentioned earlier, along with still-pervasive stereotypes that victims provoke their own victimization, reduce help-seeking behaviors and can negatively affect the attitudes of people who provide support to those who experience partner abuse.31

Legal Issues

In every state, physical abuse within domestic relationships is considered a crime; therefore, what the healthcare provider documents may have legal relevance and be crucial to successful prosecution of an abuser. Healthcare providers also need to know if reporting is mandatory in their community or state, or if the decision to involve police lies completely with the victim.23 Once a diagnosis of IPV is made or even suspected, the provider needs to establish a safe environment, evaluate the emotional status of the victim, provide emotional support, diagnose and treat any physical injuries, and clearly and thoroughly document the historical and physical findings.32

The Joint Commission clearly recognizes that unless IPV victims are identified, they will not receive appropriate care, and that these patients have specialized assessment and care needs. To provide appropriate care to these patients, hospitals must have a system in place throughout the organization to identify and assess IPV victims; staff need to be trained in the use of that system. The Joint Commission also acknowledges the forensic value of this process, and that information and evidence obtained during an initial screening process may be used in future legal actions. Thus, the hospital must have policies and procedures that define the organization’s responsibility for collecting, retaining, and safeguarding such materials, and specify who is responsible for carrying out these actions. Hospitals and practices also must maintain current information on private and public agencies that care for IPV victims and refer them appropriately.32,33

Most states have enacted mandatory reporting laws for certain types of nonaccidental trauma. These laws differ from mandatory reporting laws involving suspected child abuse or elder abuse in that they do not target any single vulnerable group. The specifics of the laws differ from state to state, but the broad categories can be defined as: those that require reporting of injuries caused by weapons; those that require reporting injuries caused in violation of criminal laws, as a result of violence, or through nonaccidental means; and those that require reporting specifically of domestic violence cases. Few states actually have stand-alone domestic violence laws that mandate physicians to document all cases of suspected IPV.34 It is important to note that even if state law mandates reporting, the victim is not obligated to speak with or cooperate with law enforcement. Although most cases of IPV that lead to legal proceedings are reported by victims, many victims do not wish to press charges initially, especially if they are still cohabitating with the abuser or have not been previous victims of domestic violence.35 This is seen most clearly in cases of alleged sexual assault. Under federal law, the Violence Against Women Act allows victims to receive a forensic medical exam following sexual assault without having to decide whether they wish to report the crime to law enforcement. Should the victim or the victim’s legal surrogate ultimately decide to report, the properly collected and stored evidence can be examined at that time.36 Despite its title, the Violence Against Women Act applies to all victims of domestic violence, irrespective of their race, color, national origin, religion, sex, gender identity, sexual orientation, or disability.37

Legislation regarding firearms varies by state. Under federal and many state laws, individuals under a domestic violence restraining order are prohibited from possessing a firearm. Twenty-eight states and Washington, DC, had passed legislation that includes specific instructions for the dispossession of firearms from prohibited individuals subject to a domestic violence restraining order. All of these laws vary in their instructions to the respondent or to law enforcement regarding how the individual is to dispossess themselves of the firearms and the time frame in which it must be done. Many states require that specific conditions be met before the court can order dispossession of firearms, focusing on the respondent’s previous acts of violence or firearms-related violence, or the risk that the respondent may use a firearm or cause physical harm.38,38

It is incumbent on the physician to be aware of the state and federal laws that guide the evaluation of IPV victims. Victims’ experiences with the medical community have significant effects on how they are able to handle and ultimately heal from their experiences. Having a supportive environment can reduce the stigmatization of IPV victims and empower them to seek further help.31 In cases of sexual assault, victim-centered programs, such as the use of a SANE, can help the victims feel safe and cared for, as well as ensure proper forensic evidence collection should legal measures be pursued.36

Identification of IPV Victims

Unfortunately, identifying instances of IPV can be quite difficult, and the best way to address this remains unclear. The majority of victims present to the ED with medical complaints as opposed to trauma complaints. Visits often are far removed from violent incidents (more than 30 days), with less than 5% of ED visits occurring on the day of abuse. Despite known high usage of EDs among this population, more than 72% of these police-recorded IPV victims are not identified as such in the ED.7 This may be because of victims hiding the abuse or assuming that an “isolated” experience last week is of no importance now, because of inadequate screening by ED staff, or because it is easier (consciously or subconsciously) for providers to turn a blind eye rather than address the complicated issue of IPV. Likely, it is a mix of all the aforementioned issues. There are many barriers to effective screening and, even then, full disclosure may not be given by the victim. Providers must be alert, as many of the signs of domestic violence and IPV are subtle. When providers are vigilant for the signs of abuse, they are more likely to recognize them, even without the use of screening questionnaires.

One reason that recognizing IPV is difficult is because the signs often are not written in black and white. IPV crosses all demographics, and both providers and patients have barriers in place that hinder open discussion on the topic. When picturing a domestic violence victim, many minds immediately will think of a woman who is young and in a low socioeconomic class. Although this victim profile may be common, IPV crosses boundaries covering all genders, ages, orientations, and races. There often is increased reporting among less educated and lower socioeconomic populations, but true data are unknown because self-identification is extremely variable.40 This stems from barriers in the screening process. Providers frequently lack the comfort, resources, and time to screen effectively, and victims struggle with embarrassment, stigma, fear of retaliation, worries about confidentiality, and concerns about losing children surrounding the conversation.15,41,42 Maintaining an open and welcoming patient interaction can help providers identify cases of domestic violence, even in demographics outside the stereotypical presentation.

Universal screening for IPV may seem to be a straightforward way to identify victims and intervene in domestic violence cases. Unfortunately, it does not appear to be this simple. (See Table 2.) Providers often believe this does not add to the visit and takes excessive time to complete, and some patients report feeling uncomfortable when being screened.43,44 Although studies suggest that universal screening leads to higher detection rates, the available research has been unable to demonstrate that this ultimately improves patient care or allows for more effective handling of domestic violence cases. It is unclear if this is because of high false-positive/false-negative questionnaire responses, inadequate referral practices, or ineffective follow-up.44 Currently, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends that universal screening be used for all females of reproductive age (14-46 years). The USPSTF has deemed this grade B evidence, as the potential benefits (increased identification and treatment) outweigh the potential harms (embarrassment and risk of increased violence).45 It is important to note that the USPSTF does not support routine screening for men or the elderly because there are fewer data to support it. Interestingly, the World Health Organization recommendations are slightly contrary to USPSTF’s, as they recommend universal screening only for pregnant women. The Joint Commission, since 2004, requires organizations to use written criteria to identify patients who may be victims of sexual assault, physical assault, domestic abuse, and child or elder neglect or abuse and to report to external agencies as required by law and regulations. Arguments can be made for each side on the effectiveness of universal screening, but for now it should continue to be standard practice, especially among reproductive age women.

Table 2. Screening for Intimate Partner Violence |

|

When universal screening is employed, multiple options are available, ranging from patient-written questionnaires, verbal intake questionnaires by staff, or direct probing questions by a provider. The USPSTF recommends numerous screening questionnaires, including Hurt, Insult, Threaten, Scream (HITS); Ongoing Abuse Screen/Ongoing Violence Assessment Tool (OAS/OVAT); Slapped, Threatened, and Throw (STaT); Humiliation, Afraid, Rape, Kick (HARK); Childhood Trauma Questionnaire – Short Form (CTQ-SF); and Woman Abuse Screen Tool (WAST).45 These are brief surveys that can rapidly identify women who raise suspicion for being IPV victims and require further investigation. For example, the HITS survey is composed of a 1-5 Likert scale, ranking from “never” to “frequently” on the occurrence of a partner physically hurting, talking down to or insulting, threatening with harm, or screaming and cursing at a female partner.46 Again, it is important to keep in mind that it is difficult to know true false-positive and false-negative rates with these surveys. Most studies show that women generally agree that domestic violence and home safety questions should be asked, with 82% agreeing in one study; however, which survey format is better is unknown.44,47 Currently, in most EDs, intake questions initially address these concerns.

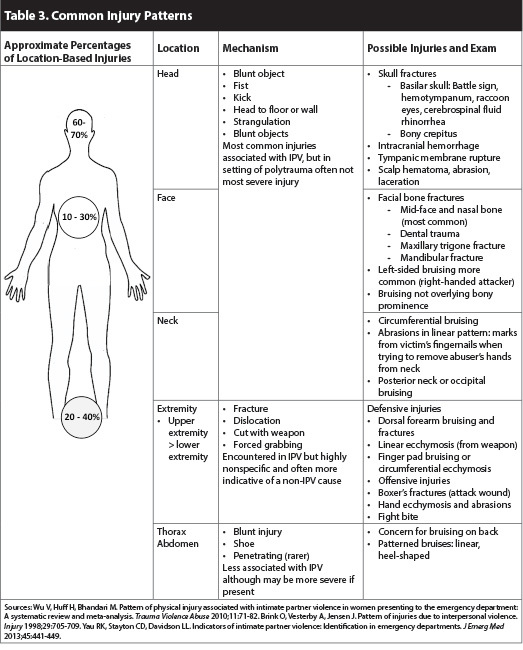

Coupled with screening questionnaires, the use of visual diagnosis and physical examination can help guide a provider suspecting domestic violence. IPV often has characteristic injury patterns, with head, neck, and facial injuries being the most common. In fact, women with these injury patterns are 7.5 to 11.8 times more likely to report domestic violence as the cause for their injuries than women with injuries isolated to other body parts. Sensitivity is high (> 95%) for injuries in these areas, although they are not specific (< 50%).15,42 Facial injuries are extremely common, with 30% having facial fractures. The mid-third of the face is the most commonly targeted and, at 40%, nasal bones are the most commonly fractured.48 Studies reviewing traumatic injuries also show a predisposition for wounds to the extremities, with upper extremity injuries more common than lower extremity ones. In a defensive situation, victims tend to use arms and legs to protect their head, face, and core. With this defensive pose, distal upper extremity injuries are the most common.49,50 For all injuries, blunt trauma is more common than penetrating trauma. In one study of 256 women, only 18 women were injured by sharp objects, and no women were shot. Blunt injuries often are from punches, but in approximately one-fourth of cases, a blunt weapon (i.e., broom, pole, gun) is used. These blows made abrasions, contusions, and ecchymosis far more common than lacerations or osseous injuries.50

As in child abuse, certain bruising patterns can raise concern for an intentional cause. Bruises to the neck, back, and face (when not on bony protrusions) are less likely to have occurred from a fall or accident. Bruise shape also can be telling of etiology. Long linear bruises or characteristic boot-heel shaped bruises can add clues; even a strong grip can leave characteristic thumb prints, finger pad bruises, or fingernail marks (inflicted by either the perpetrator or victim while fighting to remove someone’s hands from his or her neck).51 A circumferential bruise usually indicates a nonaccidental cause, and ligature or bruising around the neck or extremity also should raise suspicion.51 Looking at a patient’s wounds, both injury location and type, can help provide additional clues about etiology, allowing providers to have increased suspicion for abuse. As noted earlier, nonfatal strangulation is associated with a risk of future attempted or completed homicide, yet may leave little in the way of observable injury.21 Healthcare providers need to be particularly vigilant in searching for and documenting bruise patterns on persons of color. Bruises can be more difficult to see on the skin of African-American victims, making them more likely to be missed by police and healthcare providers.52

As part of the physical exam, it is important to note the patient’s psychiatric affect, mood, and interactions with any visitors he or she may have present. Abnormal psychiatric findings secondary to IPV can be extremely subtle and often are difficult to recognize. While not diagnostic, actions such as avoiding eye contact, looking to the partner before answering questions, or having an overbearing partner present can be worrisome. In these cases, every possible effort should be made to interview the patient individually, even if this requires discussion with the patient while in the radiology suite or out of the room providing a urine sample. Fear of retaliation is one of the key factors that dissuades victims from reporting, and this feeling is compounded if the abuser is present in the hospital setting. Clinical gestalt can go a long way in these situations, and healthcare providers should not be afraid to address their concerns repeatedly with the patient until satisfied. While they may not always present in an obvious, textbook manner, patterns of fear and coercion combined with characteristic injury patterns can aid providers in recognizing even the most subtle IPV presentations.23,24 (See Table 3 for common injury patterns.)

When screening for IPV, it is important to recognize and address any comorbid conditions the patient may have. A patient should be screened for these conditions after admitting that he or she is a victim. In cases in which the victim is not forthcoming, screening and intervention for comorbid conditions allows for continued interaction with healthcare providers and provides different avenues by which to address IPV concerns. Studies show that domestic violence victims have higher rates of psychiatric and mood conditions, such as anxiety, depression, PTSD, sleep disorders, eating disorders, and drug or alcohol abuse. Suicidality and suicide attempt rates also were much higher in abused women compared to the general population.9,12-14,53 If a patient screens positive for IPV, he or she should be screened concurrently for mental health and substance abuse. The screening process should include a referral process to appropriate agencies and linkage to available services. These additional steps are essential in treating the whole person and enhancing the odds of an effective intervention.

More studies are needed to understand how providers can better screen for IPV. Many women and men turn to EDs, clinics, and medical practices following IPV. Whether or not a victim self-identifies, providers must remain vigilant to recognize signs of domestic violence. Signs can be subtle, but early identification is necessary to help reduce the personal and societal effects of abuse.

Documentation

Identifying IPV is arguably the most important step in the ED; however, this is only the beginning of the pathway to finding help for victims. Documentation of IPV plays a central role and is critical to ensure the patient is treated adequately beyond his or her hospital stay and to ensure medicolegal protection of the provider. It is essential that healthcare providers understand what should be included in a complete domestic violence medical record.

There are many ways that providers are failing in this realm, and we need to understand the gravity of the situation. Unfortunately, documentation of IPV notoriously is done poorly. For one, the documentation threshold for domestic violence and IPV remains too high, and providers hesitate to code for it despite convincing reports and injury patterns.54 Using terms such as “domestic violence” and “intimate partner violence” carry a weight that “ecchymosis” or “fracture” do not carry, and this can lead to avoidance of the true diagnosis. At a minimum, if a screening tool shows positive results for violence, there should be some mention of this in a patient’s chart. Surprisingly, one study found that more than 10% of positive screenings for IPV showed no further documentation to address these concerns when reviewing charts.55 Emergency physicians and other healthcare providers also tend to chart injury-based diagnoses (e.g., fracture, post-traumatic headache, hematoma) more readily than to place assault or the even more descript “domestic violence” in a chart.54 As electronic medical records have grown in prevalence, simple things such as legibility of notes have improved, but historically a poorly hand-written note has been enough to make a record inadmissible in court.56

Although the main goal of documentation is better patient care, thorough documentation concurrently protects providers. If a provider is called as a witness in a domestic violence case, charted notes may be the only memory a provider carries of the event. Documentation also outlines the services provided to the patient. This includes proof of mandatory reporting, if required, as well as documentation of the resources and interventions provided to patients. Clear documentation also can help in the identification of domestic violence as providers review past records and can see trends in a patient’s medical history.

For victims of IPV, unbiased factual reports are the crux of any legal case. A well-documented ED visit can help to corroborate police reports and give testimony in a patient’s case. Although police often are involved, providers should not be dissuaded from thorough documentation under the assumption that police will handle all legal matters. Unfortunately, this is a commonly believed fallacy and has been shown to lead providers to document less when police are involved.54,56 Police and medical interactions often occur immediately following traumatic abuse, giving more weight to their assessments. Once wounds have healed and bruises have faded, a documented description of injuries may be all a victim has during legal hearings. When combined with police reports, a well-documented chart can serve as a vital tool for victims and prosecutors. Some patients may not choose to use this information immediately if they do not plan to press charges, but it is important they know the documentation will always be available in their medical records. Unbiased testimonies provided through medical documentation give patients a voice in the future and allow providers to continue caring for patients long after they are discharged.

As physicians create documentation in IPV cases, it is important to remember the central goal: objective factual documentation. This is best done by providing a clear and accurate timeline, using direct quotations, documenting mood and affect, and including a combination of both written and photographic evidence. First, as with any history and physical, there should be a clear timeline of events. For IPV in particular, it is important to include not only the events that led to the visit, but also a timeline of abuse if it has been an ongoing issue.57 Another simple way to document a patient’s history is by using direct statements from the patient. Phrases such as “my boyfriend held me against the wall” carry more weight when they are documented as direct quotes from the patient. Addressing the assailant’s relationship and actions allows no room for misinterpretation when they are in the patient’s voice. Immediately following a traumatic event, details about what occurred may be clearer, and the patient is more likely to make spontaneous exclamations about the stressful event. Words said in response to a triggering event can fill the legal requirement for “excited utterances.” These are statements made acutely following traumatic events and are admissible in court even months afterward because of the weight they carry.56

It is important to avoid language that could cast doubt on a patient’s credibility. This includes commonly used statements such as “alleged” or “the patient claims.” If such words are used, there should be justification for why one might doubt the patient’s story.54,57 Whenever possible, a complete chart should include pictorial representation in addition to the written documentation. Ideally this should be with photographs to provide concrete evidence of the bruises and wounds that may have healed before legal proceedings. A body map, available on several electronic records and paper-based template charts, is a valuable resource if cameras and photos cannot be linked to a chart. Written documentation is critical, but many times a picture is worth a thousand words, especially in court.56,57

Medical decision-making should include management beyond care for the patient’s physical injuries. It should discuss if mandatory reporting was initiated, as well as provide clear evidence of resources provided, referrals, and safe disposition planning. In these ways, medical providers can protect themselves and their patients effectively while creating a forensically useful chart.

Disposition and Safety Planning

After treating a victim’s medical needs, it is important to ensure a safe disposition, whether the patient will be discharged or admitted for his or her injuries. This often is managed poorly in practice because busy providers frequently lack the resources and time to address the patient’s needs fully. Studies suggest that concerns about safe discharge planning may be one factor that deters providers from screening for IPV. This stems from the worry that they will not be able to treat the patient adequately if the screening is positive.40,58,59 A large part of this is the fear of discharging a patient back into a dangerous environment without effective resources. Although clear guidelines are not established about what is most helpful to discharge IPV victims safely, a few overarching themes can help guide management. These include mortality risk assessments, safety planning, a diverse referral basis, and a team-based approach. These elements ensure that all aspects of a patient’s care are covered in a thorough and time-efficient manner in high-turnover EDs.

Traumatically injured patients or those with clear acute medical pathology tend to be more straightforward admissions; however, a dilemma arises for patients who might be discharged and returning to a dangerous or even potentially lethal environment. If a patient feels safe to leave but the provider still has reservations, this can create conflict and further complicate management. In these situations, there are multiple sources urging the use of brief standardized questionnaires to assess mortality/lethality risk of discharging victims.

One study looked at multiple questions to assess such risk and narrowed them to five primary questions that increase the chance of recurrent near-fatal trauma.60 The study recommends that any patient who answers “yes” to three of five questions be labeled as high risk. (See Table 4.) The questionnaire had a sensitivity of 83% in identifying those who would have return ED visits with near-fatal injuries. Although not specifically addressed in the study, another factor to consider is the physical presence of firearms in the home. As noted earlier, the presence of a firearm in the home increases the risk of homicide significantly, and providers need to address if there are legal grounds for having firearms removed before allowing a victim to return home.20,38

Table 4. Example Mortality Risk Assessment Tool |

Three of five affirmative answers are concerning for high risk of near fatal recurrent abuse.

|

Source: Adapted from Snider C, Webster D, O’Sullivan CS, Campbell J. Intimate partner violence: Development of a brief risk assessment for the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med 2009;16:1208-1216. |

An example of a useful screening tool is the Danger Assessment Tool, developed in 1986 by Dr. Jacquelyn Campbell in consultation with IPV victims, shelter workers, law enforcement officials, and other clinical experts. Using a calendar to pinpoint abuse frequency during the past year, along with a 20-item questionnaire, the screening accurately identifies IPV victims at risk for death.61,62 Law enforcement, social workers, and healthcare providers all can obtain certification to use the screening.

For patients who are unable to be discharged, some medical centers have availability for admission; otherwise, patients may require referrals to shelters or alternative housing through a social worker.2

For patients who will be returning home, a personal safety plan is essential for continued empowerment and support. Safety plans take many forms and must be molded to each individual’s needs depending on the type of abuse, presence of children, cohabitation, patient’s coping mechanisms, and the available support systems. At a minimum, a safety plan should include emergency contacts, a plan if violence returns, a plan for leaving (to include finances, housing, and resource access), and involvement of family or friends. Ideally, these should be written plans to provide a usable guideline if the person needs to take action when abuse returns. Thinking clearly in the midst of a significant stressor such as abuse can be difficult, and a pre-formulated safety and response plan can bring clarity during those stress-laden times. Safety planning responsibilities often can fall on social workers, but in smaller EDs this may need to be addressed by physicians, nurses, or other healthcare providers. The National Domestic Violence Hotline website has multiple suggestions for victims working to establish a safety plan, and is a valuable resource that providers can give to their patients.63

Beyond safety planning and in-hospital interventions, IPV victims have many needs that must be addressed in their recovery. This is where effective referrals come into play. Referrals fall into multiple categories, including other medical providers, social workers, mental health and substance abuse counseling, housing and shelters, law enforcement, legal counseling, spiritual counseling, financial counseling, and education. Resource needs and availability differ from patient to patient. There is no consensus on the most effective referrals in a victim’s recovery, but there is agreement that a multifaceted approach is needed.28,64 At a minimum, a brief psychiatric evaluation should be performed with referrals placed if needed, substance abuse screening and resources offered, child protective services called if children are present in the home, legal and police services offered, and housing information given if there is an immediate safety risk. Beyond provider referrals, brochures and printed materials can be helpful, but patients also should be referred to online resources such as the National Domestic Violence Hotline.63 Small details can fall through the cracks easily, so having standardized intake sheets can help minimize errors.

As with safety planning, responsibility for disposition planning varies, and many strategies are used. Nursing staff often help with screening and can aid in resource referrals. Social workers or even specialized IPV teams also can allow the physician to offload responsibility, thereby helping overall patient flow.2

Conclusion

Ultimately, physicians need to be sure an adequate evaluation has been performed and an appropriate plan is in place. Through using mortality risk assessment tools, safety planning, a broad resource referral basis, and a team-based approach, healthcare professionals can provide the initial framework for a victim’s continued recovery. A brief ED stay rarely will resolve an IPV victim’s underlying situation, but if done effectively, safe discharge planning and referrals can start the recovery process.

REFERENCES

1. Wu V, Huff H, Bhandari M. Pattern of physical injury associated with intimate partner violence in women presenting to the emergency department: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Trauma Violence Abuse 2010;11:71-82.

2. Choo EK, Houry DE. Managing intimate partner violence in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med 2015;65:447-451.

3. Hamberger LK, Rhodes K, Brown J. Screening and intervention for intimate partner violence in healthcare settings: Creating sustainable system-level programs. J Women’s Health (Larchmt) 2015;24:86-91.

4. Boserup B, McKenney M, Elkbuli A. Alarming trends in US domestic violence during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Emerg Med 2020;38:2753-2755.

5. Kourti A, Stavridou A, Panagouli E, et al. (2023). Domestic violence during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse 2023;24:719-745.

6. Davidov DM, Larrabee H, Davis SM. United States emergency department visits coded for intimate partner violence. J Emerg Med 2015;48:94-100.

7. Rhodes KV, Kothari CL, Dichter M, et al. Intimate partner violence identification and response: Time for a change in strategy. J Gen Intern Med 2011;26:894-899.

8. Joseph B, Khalil M, Zangbar B, et al. Prevalence of domestic violence among trauma patients. JAMA Surg 2015;150:1177-1183.

9. Hink AB, Toschlog E, Waibel B, Bard M. Risks go beyond the violence: Association between intimate partner violence, mental illness, and substance abuse among females admitted to a rural Level I trauma center. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2015;79:709-716.

10. Erickson MJ, Gittelman MA, Dowd D. Risk factors for dating violence among adolescent females presenting to the pediatric emergency department. J Trauma 2010;69:S227-S232.

11. Stöckl H, March L, Pallitto C, et al. Intimate partner violence among adolescents and young women: Prevalence and associated factors in nine countries: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2014;14:751.

12. Bazargan-Hejazi S, Kim E, Lin J, et al. Risk factors associated with different types of intimate partner violence (IPV): An emergency department study. J Emerg Med 2014;47:710-720.

13. Gilbert L, El-Bassel N, Chang M, et al. Substance abuse and partner violence among urban women seeking emergency care. Psychol Addict Behav 2012;26:226-235.

14. Lipsky S, Caetano R. Intimate partner violence perpetration among men and emergency department use. J Emerg Med 2011;40:696-703.

15. Beydoun HA, Williams M, Beydoun MA, et al. Relationship of physical intimate partner violence with mental health diagnoses in the nationwide emergency department sample. J Women’s Health (Larchmt) 2017;26:141-151.

16. Peitzmeier SM, Malik M, Kattari SK, et al. Intimate partner violence in transgender populations: Systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence and correlates. Am J Public Health 2020;110:e1-e14.

17. Hackenberg EAM, Sallinen V, Koljonen V, Handolin L. Severe intimate partner violence affecting both young and elderly patients of both sexes. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg 2017;43:319-327.

18. Brignone L, Gomez AM. Double jeopardy: Predictors of elevated lethality risk among intimate partner violence victims seen in emergency departments. Prev Med 2017;103:20-25.

19. Little D. Patterned injuries. Pathology 2011;43:S24.

20. Diez C, Kurland RP, Rothman EF, et al. State intimate partner violence-related firearms laws and intimate partner homicide rates in the United States, 1991 to 2015. Ann Intern Med 2017;167:536-543.

21. Glass N, Laughon K, Campbell J, et al. Non-fatal strangulation is an important risk factor for homicide of women. J Emerg Med 2008;35:329-335.

22. Murray S. “Why doesn’t she just leave?”: Belonging, disruption and domestic violence. Women’s Studies International Forum 2008;31:65-72.

23. Sheridan DJ. Treating survivors of intimate partner abuse: Forensic identification and documentation. In: Olshaker JS, Jackson MC, Smock WS, eds. Forensic Emergency Medicine. 2nd ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins;2007:202-222.

24. Eckstein JJ. Reasons for staying in intimately violent relationships: Comparisons of men and women and messages communicated to self and others. J Fam Violence 2011;26:21-30.

25. Prosman GJ, Lo Fo Wong SH, Lagro-Janssen AL. Why abused women do not seek professional help: A qualitative study. Scand J Caring Sci 2014;28:3-11.

26. Rhodes KV, Cerulli C, Dichter ME, et al. “I didn’t want to put them through that”: The influence of children on victim decision-making in intimate partner violence cases. J Fam Viol 2010;25:485-493.

27. Enander V, Holmberg C. Why does she leave? The leaving process(es) of battered women. Health Care Women Int 2008;29:200-226.

28. Postmus JL, Severson M, Berry M, Yoo JA. Women’s experiences of violence and seeking help. Violence Against Women 2009;15:852-868.

29. Copel LC. The lived experience of women in abusive relationships who sought spiritual guidance. Issues Ment Health Nurs 2008;29:115-130.

30. World Health Organization. Changing cultural and social norms that support violence. World Health Organization Series of Briefings on Violence Prevention 2009. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/44147/9789241598330_eng.pdf?sequence=1

31. Overstreet NM, Quinn DM. The intimate partner violence stigmatization model and barriers to help-seeking. Basic Appl Soc Psych 2013;35:109-122.

32. Burnett LB. Domestic violence. eMedicine 2018. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/805546-overview

33. Futures Without Violence. Joint Commissions Standard PC 01.02.09 on Victims of Abuse. Available at: https://www.futureswithoutviolence.org/joint-commissions-standard-pc-01-02-09-on-victims-of-abuse/

34. Durborow N, Lizdas KC, O’Flaherty A, Marjavi A. Compendium of State Statutes and Policies on Domestic Violence and Health Care. Family Violence Prevention Fund; 2010. https://www.futureswithoutviolence.org/userfiles/file/HealthCare/Compendium%20Final.pdf

35. Boivin R, Leclerc C. Domestic violence reported to the police: Correlates of victims’ reporting behavior and support to legal proceedings. Violence Vict 2016;31:402-415.

36. Riviello RJ, Rozzi HV. Know the legal requirements when caring for sexual assault victims. ACEP Now 2018;37:29,31,33.

37. National Task Force to End Sexual and Domestic Violence. http://www.4vawa.org/

38. Zeoli AM, Frattaroli S, Roskam K, Herrera AK. Removing firearms from those prohibited from possession by domestic violence restraining orders: A survey and analysis of state laws. Trauma Violence Abuse 2017;20:114-125.

39. Sidorsky K, Schiller W. Can government protect women from domestic violence? Not if states do not follow up. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/fixgov/2023/03/21/can-government-protect-women-from-domestic-violence-not-if-states-do-not-follow-up/

40. Daugherty JD, Houry, DE. Intimate partner violence screening in the emergency department. J Postgrad Med 2008;54:301-305.

41. Williams JR, Halstead V, Salani D, Koermer N. An exploration of screening protocols for intimate partner violence in healthcare facilities: A qualitative study. J Clin Nurs 2017;26:2192-2201.

42. Perciaccante VJ, Carey JW, Susarla SM, Dodson TB. Markers for intimate partner violence in the emergency department setting. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2010;68:1219-1224.

43. Ramsay J, Richardson J, Carter YH, et al. Should health professionals screen women for domestic violence? Systematic review. BMJ 2002;325:314.

44. O’Doherty L, Hegarty K, Ramsay J, et al. Screening women for intimate partner violence in healthcare settings. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015;7:CD007007.

45. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Recommendation Statement: Intimate Partner Violence, Elder Abuse, and Abuse of Vulnerable Adults: Screening. 2018. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/intimate-partner-violence-and-abuse-of-elderly-and-vulnerable-adults-screening

46. Rabin RF, Jennings JM, Campbell JC, Bair-Merritt MH. Intimate partner violence screening tools: A systematic review. Am J Prev Med 2009;36:439-445.

47. Koziol-McLain J, Garrett N, Fanslow J, et al. A randomized controlled trial of a brief emergency department intimate partner violence screening intervention. Ann Emerg Med 2010;56: 413-423.

48. Le BT, Dierks EJ, Ueeck BA, et al. Maxillofacial injuries associated with domestic violence. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2010;59:1277-1283.

49. Brigham and Women’s Hospital. Radiologists detect injury patterns of intimate partner violence: Study finds that radiology images can offer evidence indicative of domestic abuse. ScienceDaily. Nov. 27, 2017. www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2017/11/171127090822.htm

50. Kyriacou DN, Anglin D, Taliaferro E, et al. Risk factors for injury to women from domestic violence. N Engl J Med 1999;341:1892-1898.

51. Greenberg M. Bruise interpretation: Tips for abuse investigations. PoliceOne.com. July 30, 2013. https://www.policeone.com/investigations/articles/6342356-Bruise-interpretation-Tips-for-abuse-investigations/

52. Deutsch LS, Resch K, Barber T, et al. Bruise documentation, race and barriers to seeking legal relief for intimate partner violence survivors: A retrospective qualitative study. J Fam Viol 2017;32:767-773.

53. Heise L, Garcia Moreno C. Violence by intimate partners. In: Krug EG, Dahlberg LL, Mercy JA, et al, eds. World Report on Violence and Health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2002:87-121.

54. Olive P. Classificatory multiplicity: Intimate partner violence diagnosis in emergency department consultations. J Clin Nurs 2017;26:2229-2243.

55. Sutherland MA, Fontenot HB, Fantasia HC. Beyond assessment: Examining providers’ responses to disclosures of violence. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract 2014;26:567-573.

56. Isaac NE, Enos VP. Documenting domestic violence: How health care providers can help victims. National Institute of Justice Research in Brief 2001; Washington DC: National Institute of Justice. US Department of Justice. https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/188564.pdf

57. Lentz L. 10 tips for documenting domestic violence. Nursing 2010;40:53-55.

58. Gerber MR, Leiter KS, Hermann RC, Bor DH. How and why community hospital clinicians document a positive screen for intimate partner violence: A cross-sectional study. BMC Fam Pract 2005;6:48.

59. Elliott L, Nerney M, Jones T, Friedmann PD. Barriers to screening for domestic violence. J Gen Intern Med 2002;17:112-116.

60. Snider C, Webster D, O’Sullivan CS, Campbell J. Intimate partner violence: Development of a brief risk assessment for the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med 2009;16:1208-1216.

61. Campbell JC, Webster DW, Glass N. The danger assessment: Validation of a lethality risk assessment instrument for intimate partner femicide. J Interpers Violence 2009;24:653-667.

62. Johns Hopkins School of Nursing. What is the danger assessment? https://www.dangerassessment.org/

63. The National Domestic Violence Hotline. https://www.thehotline.org

64. Kendall J, Pelucio MT, Casaletto J, et al. Impact of emergency department intimate partner violence intervention. J Interpers Violence 2009;24:280-306.

Domestic violence and abuse is a national and global healthcare problem with massive consequences, affecting men, women, and children, which worsened during the COVID-19 pandemic. Awareness, recognition, and resource allocation, in addition to trauma management, is an important aspect of emergent care of the trauma patient possibly injured in a domestic violence incident.

Subscribe Now for Access

You have reached your article limit for the month. We hope you found our articles both enjoyable and insightful. For information on new subscriptions, product trials, alternative billing arrangements or group and site discounts please call 800-688-2421. We look forward to having you as a long-term member of the Relias Media community.