Identifying and Treating Skin and Soft Tissue Infections

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

- Erysipelas and impetigo are infections of the epidermis.

- Cellulitis and cutaneous abscesses are infections primarily of the dermis.

- Community-acquired skin and soft tissue infections in healthy individuals most commonly are caused by Staphylococcus aureus and beta-hemolytic streptococci.

- A broader range of microorganisms are associated with skin and soft tissue infections due to injection drug use, human and animal bites, water exposure, and diabetes.

- Orbital cellulitis is differentiated from periorbital cellulitis by impairment of and pain with extraocular movement.

- The classic clinical triad of a necrotizing soft tissue infection is swelling, erythema, and pain out of proportion.

- The mainstay treatment for necrotizing soft tissue infections is surgical debridement of infected tissue, ideally within six hours of presentation.

Skin and soft tissue infections (SSTIs) refer to infections that affect the skin and its underlying soft tissues. These infections are classified by the level of skin involvement.

The skin is composed of the following layers: the epidermis, dermis, and hypodermis. The epidermis is the most superficial layer. The epidermis contains cell types with different functions, such as keratinocytes, melanocytes, Merkel cells, and Langerhans cells. Keratinocytes produce keratin and maintain the epidermal water barrier. Melanocytes produce melanin that protects against ultraviolet (UV) radiation. Merkel cells are sensory cells, and Langerhans cells are T lymphocytes that serve as the skin’s defenders. Infections of the epidermis include erysipelas and impetigo. Erysipelas is a non-purulent infection that affects only the epidermis, while impetigo is an infection that targets only the keratin cells within the epidermis.1

The dermis is deep to the epidermis and is composed of two layers: the papillary layer and the reticular layer. The dermis contains sweat glands, hair follicles, muscles, sensory neurons, and blood vessels. Folliculitis is an infection that is localized to the hair follicles.1

The hypodermis is the deepest layer of the skin. It houses adipose lobules, deeper portions of hair follicles, sensory neurons, and more blood vessels. Hair follicles can serve as a point of entry for Staphylococcus aureus infections, specifically in the form of furuncles.1 Carbuncles are formed by the coalescence of multiple furuncles and tend to extend deeper into the hypodermis.1 The fascia is a layer of connective tissue that lies below the hypodermis, and necrotizing fasciitis is an infection that spreads along this layer.

Infections occur when the protective barriers of the skin are disrupted and, without proper treatment, may lead to serious complications, such as necrosis and septic shock. Risk factors that can make patients more susceptible to SSTIs include diabetes, immunocompromise, obesity, and older age.1

Epidemiology

The costs associated with Staphylococcus aureus skin and soft tissue infections are estimated at an average of $8,865 for both inpatient and outpatient treatment, and a median charge of $19,984 for hospitalizations.2,3 These costs can place a significant burden on both patients and the healthcare system. Timely and accurate diagnosis and treatment can help to reduce this burden, both financially and by decreasing the risk of complications.

Microbiology

Community-acquired skin and soft tissue infections in healthy individuals most commonly are caused by two microorganisms: Staphylococcus aureus and groups A, B, C, and G β-hemolytic streptococci.4 These microorganisms are gram-positive, with S. aureus appearing in clusters and streptococcal organisms growing in chains. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) can be a challenging infection to treat, especially with varying resistance patterns based on geographic location. Common causative microorganisms for specific circumstances are noted in Table 1.

Table 1. Special Circumstances and Infectious Causes of Skin and Soft Tissue Infections |

|

Injection drug use |

Streptococcus spp., Clostridium novyi, Clostridium sordelli, and Clostridium perfringens |

Water exposure |

Vibrio vulnificus, Aeromonas hydrophilia, Mycobacterium marinum, and Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae |

Diabetic foot infections |

Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Escherichia coli, and Enterococcus spp. |

Human bites |

Streptococcus spp., S. aureus, Fusobacterium nucleatum, Peptostreptococcus spp., and Eikenella corrodens |

Cat bites |

S. aureus, Streptococcus spp., Bartonella henselae, Fusobacterium spp., Pasteurella multocida, Capnocytophaga spp., and Bacteroides spp. |

Dog bites |

S. aureus, Streptococcus spp., Capnocytophaga canimorsus, Fusobacterium spp., Pasteurella multocida, Pasteurella canis, and Bacteroides spp. |

Staphylococcus aureus is commonly found on the human body as part of the normal microbiota. It is found most often on the nasal mucosa, gastrointestinal tract, and skin, especially in moist areas such as the axilla and groin. S. aureus typically produces localized pus-producing lesions, such as furuncles, abscesses, and carbuncles. S. aureus elaborates various exotoxins that recruit neutrophils, cause host cell lysis, and are involved in the formation of the fibrin capsule surrounding abscesses, which allows for the accumulation of pus.4

The emergence of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (CA-MRSA) in the late 1990s and early 2000s resulted in a significant increase in purulent skin and soft tissue infections. This required a shift in the antibiotics used to treat these infections. The most prevalent clonal type of CA-MRSA in the United States is known as USA300. This strain consistently produces Panton-Valentine leukocidin, a toxin that is lethal to white blood cells and was a major contributor to the rapid spread of CA-MRSA across the country.5,6 The ecology of S. aureus and CA-MRSA is important to consider in clinical management.

Because CA-MRSA colonizes the axilla, groin, and gastrointestinal tract, detection of colonization and decolonization strategies cannot be limited to the anterior nares alone.7 Furthermore, since S. aureus is capable of surviving on fomites, infection control measures should include disinfecting high-touch household surfaces and linen. Additionally, the purulent nature of S. aureus infections can lead to transmission from person to person through even brief direct contact with a draining lesion.8

Beta-hemolytic streptococci also are a part of the normal human skin microbiome. Unlike S. aureus, a key feature of streptococcal SSTIs is the absence of purulence, although serous fluid-filled blisters can occur during severe inflammation. The most common and well-known species is Streptococcus pyogenes, also known as group A Streptococcus, but other species, such as groups G, D, and B, are increasingly recognized as causes of non-purulent cellulitis.

S. pyogenes is a major human pathogen responsible for a wide range of clinical infections, including impetigo, lymphangitis, erysipelas, cellulitis, necrotizing fasciitis, pharyngitis, scarlet fever, pneumonia, streptococcal toxic shock syndrome, and the post-infection consequences such as rheumatic fever and glomerulonephritis.9

Clinical Features and Pathophysiology

Skin and soft tissue infections can be described by different approaches, such as anatomic location, causative pathogen(s), rate of progression, depth of infection, and severity of clinical presentation.10 Infections of the skin can be delineated by the affected skin layer. Impetigo is an infection of the most superficial layer of the epidermis. Erysipelas occurs in the next layer deep, and cellulitis occurs deeper in the dermis. Folliculitis, furuncles, and carbuncles are infections surrounding the hair follicle.

There also are specialized types of cellulitis. Periorbital cellulitis and orbital cellulitis involve the skin and soft tissue around the eye or in the eye socket, respectively. Ludwig’s angina is a life-threatening infection of the submandibular region. Abscesses — a defined collection of pus in the skin and soft tissue — can occur in specific locations, such as peritonsillar, dental, breast, Bartholin gland, gluteal cleft, anorectal, or the axilla, especially in the setting of hidradenitis suppurativa. There also are unique infections of the hand, such as paronychia and felon, that can progress into a hand-threatening infection called pyogenic flexor tenosynovitis.

The most clinically significant skin and soft tissue infections are those that produce tissue necrosis. These infections rapidly progress and are life-threatening. Special necrotizing infections include Fournier’s gangrene, gas gangrene, and water- and soil-borne necrotizing infections.10

Around the Hair Follicle

Folliculitis is an infection of the hair follicle at the epidermal layer of the skin. Folliculitis appears as multiple, small, erythematous lesions that form a pustule or papules on hair-covered skin.11 A furuncle is an infection around the hair follicle that extends into the dermis and forms a small abscess in the subcutaneous tissue.10 A furuncle usually originates from preexisting folliculitis. A carbuncle is a group of interconnected furuncles.10 Carbuncles appear as large, painful swellings with multiple pus-discharging openings and constitutional symptoms including fever and malaise.12

Folliculitis, furuncles, and carbuncles usually occur in areas of skin subject to rubbing, occlusion, and sweating, such as the face, neck, axillae, and buttocks.13 Risk factors for folliculitis include diabetes, obesity, prolonged use of oral antibiotics, immunosuppression, immunocompromised condition, or frequent shaving.12 Diagnosis primarily is a clinical one based on physical examination findings.12,13

Infections of the Skin

Infections of the skin can be described based on the skin layer involved. Impetigo is an infection of the superficial layers of the epidermis.14 Erysipelas is an infection involving the dermis layer and can extend into superficial cutaneous lymphatics.15 Cellulitis is an infection of the dermis and dermal lymphatics and extends into the subcutaneous tissue.9

Impetigo presents as erythematous plaques with yellow crust.14 Impetigo frequently occurs in children ages 2 to 5 years of age in hot, humid climates, with peak incidence in the summer and fall. Impetigo is highly contagious. Impetigo typically affects the face, but it can affect other parts of the body.14 Patients are susceptible to infection due to breakdown of skin, including abrasion, laceration, varicella, herpes, insect bite, or other trauma.

There are two types of impetigo: non-bullous and bullous. Non-bullous impetigo starts as a vesicle or pustule on an erythematous base. Multiple vesicles subsequently coalesce and rupture, releasing purulent exudate making the honey-colored crust. Non-bullous impetigo spreads rapidly, and satellite lesions can form due to self-inoculation. Systemic symptoms typically are absent in non-bullous impetigo.14

Bullous impetigo appears as small vesicles that become flaccid bullae with surrounding erythema and edema. Bullae contain clear yellow fluid that can eventually progress to become purulent or dark. Bullous impetigo does not form a honey-colored crust, and there are fewer lesions than with non-bullous impetigo. Bullous impetigo is more likely to have systemic symptoms such as fever. Bullous impetigo is more common in infants, with 90% of cases in children younger than 2 years of age. Impetigo is a clinical diagnosis based on symptoms and physical exam.14

Erysipelas presents as clearly demarcated salmon red lesions.9 Lesions typically are tender and painful with possible burning and itching at the site. Erysipelas is most common on the lower extremities, and the second most common location is on the face. Patients can have systemic symptoms, such as malaise, fever, and chills, 48 hours prior to the onset of skin lesions. Erysipelas often occurs after a violation in the skin leads to inoculation of the eliciting bacteria. Breaks in the skin often occur due to insect bites, stasis ulceration, surgical incisions, and venous insufficiency. Facial cellulitis also can be caused by recent infection of the nasopharynx passage.

Risk factors for erysipelas are obesity, lymphedema, athlete’s foot, leg ulcers, eczema, intravenous (IV) drug use, poorly controlled diabetes, and liver disease. Erysipelas is a clinical diagnosis. Patients may have leukocytosis, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and/or elevated C-reactive protein (CRP). However, these laboratory tests do not change management and are not necessary for diagnosis and treatment of erysipelas.15

Cellulitis is an infection of the dermis of the skin and extends into the dermal lymphatics and subcutaneous tissue. Cellulitis presents as swelling and macular erythema of the skin.9 There is evidence of local inflammation with warmth, erythema, and pain.9,16 (See Figure 1.) Cellulitis can have associated lymphangitis and tender regional lymphadenopathy and even systemic symptoms, such as fever and leukocytosis.9 Compared to erysipelas with clearly demarcated borders and faster development, cellulitis has ill-defined borders and is slower to develop.16

Figure 1. Cellulitis |

|

Source: Image used with permission from Benjamin Tartter, DO. |

Risk factors for cellulitis are increasing age, obesity, chronic leg edema, and previous cellulitis infection.16 Cellulitis is a clinical diagnosis that usually does not require laboratory testing. The prevalence of bacteremia in healthy individuals with uncomplicated cellulitis is low, so blood cultures are not recommended unless the patient is immunocompromised, neutropenic, has systemic signs of an inflammatory response, or did not respond to first-line therapy.9

Cellulitis caused by human and animal bites often is caused by bacteria other than staphylococcal or streptococcal species. Cellulitis associated with human bites is caused by Streptococcus spp., S. aureus, Peptostreptococcus spp., Fusobacterium spp., and Eikenella spp. Cellulitis from dog bites may be caused by bacteria such as Pasteurella spp., Bacteroides spp., Fusobacterium spp., Capnocytophaga canimorsus, Streptococcus spp., and S. aureus. Lastly, cellulitis caused by cat bites includes organisms such as S. aureus, Streptococcus spp., Pasteurella spp., Capnocytophaga spp., Bartonella henselae, Bacteroides spp., and Fusobacterium spp.9

Special Varieties of Cellulitis

Cellulitis can affect any body area.16 There are unique considerations that should be taken for specific types of cellulitis, such as periorbital cellulitis, orbital cellulitis, and Ludwig’s angina.

Periorbital cellulitis is an infection of the eyelid and area around the eye.17 Periorbital cellulitis is defined as affecting the structures in front of the septum or the membrane that separates the exterior part of the eyelid from the back part. Periorbital cellulitis presents as swelling, redness, pain, and tenderness usually around only one eye. Key clinical features of periorbital cellulitis are that the patient can move the globe in all directions without pain and vision is normal. (See Table 2.) The patient may have difficulty with opening the eyelid.17

Table 2. Clinical Features Used to Differentiate Periorbital and Orbital Cellulitis |

|

Periorbital Cellulitis |

Orbital Cellulitis |

Affects skin and soft tissue in front of the orbital septum |

Affects tissues deep to the orbital septum |

Painless extraocular movements |

Pain with extraocular movements |

Normal extraocular movement |

Impaired extraocular movement |

Normal visual acuity |

Vision changes (double or blurry) |

May have pain with opening eyelid |

Proptosis |

Orbital cellulitis is a serious, sight-threatening infection of the eye socket and tissues around it.18 Orbital cellulitis involves the eyeball itself, the fat around the eyeball, and the nerves that go to the eye. Orbital cellulitis presents as swelling, redness, pain, and tenderness to touch around one eye.18 The patient also can have proptosis and chemosis.9

Key clinical features of orbital cellulitis are that the patient has significant pain with extraocular movements and double or blurry vision. Patients may present with vision changes due to pressure on the optic nerve.18 Orbital cellulitis can occur as a complication of a sinus infection; trauma to the eye; infection of the tear duct, teeth, ear, or face; or spread of periorbital cellulitis. If orbital cellulitis is suspected, a computed tomography (CT) scan with contrast should be obtained and ophthalmology should be consulted.18

Ludwig’s angina is a life-threatening cellulitis of the submandibular region.11,19 Patients present with tender, symmetric, woody, or indurated floor of the mouth with submandibular swelling. The floor of the mouth may be erythematous and elevated.19 The outer neck also may be erythematous and edematous, with sublingual, submental, or cervical lymphadenopathy. Trismus is a possible late finding and indicates extension into the parapharyngeal space. Meningismus indicates extension into the retropharyngeal space.

As infection rapidly progresses, the patient may assume a tripoding position to maximize their airway diameter. The patient also may indicate respiratory distress and impending respiratory failure with difficulty breathing, stridor, cyanosis, and mental status changes. Edema of the airway structures can progress rapidly, occurring within 30 to 45 minutes of initial presentation.

Risk factors for Ludwig’s angina are recent dental infection, oral piercings, immunosuppression, malnutrition, diabetes, oral or dental trauma, IV drug use, or chronic alcohol use. Odontogenic infections account for 70% of Ludwig’s angina. Blood cultures should be drawn, but no other laboratory testing is necessary for diagnosis and management. If the patient is stable and can safely leave the facility and lay supine, a CT scan of the neck with IV contrast is beneficial to determine the location and extent of the infection.19

Abscess

An abscess is a collection of pus within the dermis and can extend into the deeper tissues.13 Patients present with a painful, tender, and often fluctuant red nodule surrounded by a rim of erythematous swelling. Palpable fluctuance to distinguish an abscess from non-purulent induration is neither sensitive nor specific.13 Clinical examination to distinguish cellulitis from abscess can be incorrect in up to 22% of cases.

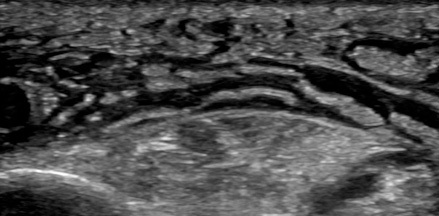

Point-of-care ultrasound can visualize the purulent collection of an abscess. Point-of-care ultrasound reduces failure-to-diagnose rate and decreases the number of inappropriate incision and drainage procedures of cellulitis.20 Cellulitis on ultrasound shows scattered fluid pockets in a cobblestoning pattern (see Figure 2), whereas an abscess will show a distinct fluid collection.21 (See Figure 3.)

Figure 2. Ultrasound of Cellulitis |

|

Source: Image used with permission from Andrea Kaelin, MD. |

Figure 3. Ultrasound of Abscess |

|

Source: Image used with permission from Andrea Kaelin, MD. |

Infections of the Hand

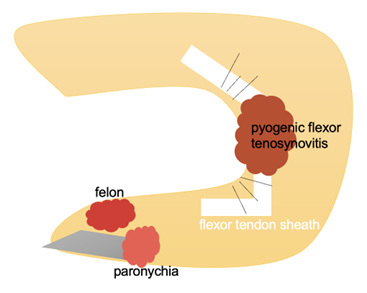

A paronychia is an infection of the proximal and lateral fingernail and toenail folds or cuticle. (See Figure 4.) A paronychia occurs due to disruption of the protective barrier between the nail and the nail fold and subsequent introduction of bacteria. Paronychia presents as an erythematous, swollen, tender lateral nail fold. There may be fluctuance at the lateral nail fold if an abscess is present as well. The diagnosis is clinical based on history and physical examination.22 Risk factors for paronychias include artificial nails or recent manicure, occupational trauma (i.e., dishwashers), ingrown nails, nail biting, or thumb sucking.22

Figure 4. Infections of the Hand |

|

A felon is an infection involving the pulp of the digit.23 A felon can be caused by a puncture wound or spread from a paronychia. A felon presents as severe throbbing pain, tense swelling, and erythema of the finger pad. The infection does not spread proximal to the distal interphalangeal joint.23

Pyogenic flexor tenosynovitis is an infection of the flexor tendon sheath.24 Kanavel signs used to identify pyogenic flexor tenosynovitis include diffuse finger swelling, finger held in a flexed posture, pain with passive digital extension, and tenderness along the flexor tendon sheath.24 Fusiform swelling is the most common sign and is seen in 97% of patients with pyogenic flexor tenosynovitis.23,24 Pain along the flexor tendon sheath may be a late sign. Only 54% of patients have all four Kanavel signs.

The diagnosis of flexor tenosynovitis is clinical.23 An X-ray should be performed to look for underlying fracture, retained foreign body, or evidence of osteomyelitis. The radiograph of pyogenic flexor tenosynovitis shows more prominent volar edema than dorsal soft tissue swelling at the proximal interphalangeal joint.25

Necrotizing Skin and Soft Tissue Infections

Necrotizing skin and soft tissue infections are severe, invasive infections with a necrotizing component involving any or all layers of the soft tissue. Necrotizing infections are life-threatening and rapidly progressive.26 The classic clinical triad of a necrotizing soft tissue infection is swelling, erythema, and pain out of proportion. Patients often have skin bullae, skin necrosis, tenderness, and palpable crepitus due to subcutaneous gas formation. (See Figure 5.) Patients also may have systemic signs of infection, such as fever, tachycardia, hypotension, and shock.

Figure 5. Necrotizing Fasciitis |

|

Source: Image used with permission from Dalia Sheridan, PA-C. |

Comorbidities associated with necrotizing infection include diabetes, renal insufficiency, arterial occlusive disease, IV drug use, obesity, older age, liver disease, immunosuppression, recent surgery, and traumatic wounds. Diabetes is the most common comorbidity, since people with diabetes have impaired wound healing and, therefore, increased susceptibility to infection.26 One-fourth of patients with a necrotizing skin or soft tissue infection have no obvious predisposing factor.27 Up to 71% of cases are missed at the first presentation.27

Laboratory testing is not sensitive or specific for necrotizing skin and soft tissue infections.26 The Laboratory Risk Indicator for Necrotizing Fasciitis (LRINEC) score is a tool developed to assess the likelihood of necrotizing infection vs. severe infection. (See Table 3.) A LRINEC score of 8 or higher suggests a 75% risk of a necrotizing soft tissue infection. However, the LRINEC score has a low sensitivity, and a low score does not rule out the diagnosis.

Table 3. LRINEC Score29 |

||

Laboratory Test |

Result |

Score |

C-reactive protein |

≥ 150 mg/L |

4 |

White blood cell count |

15,000-25,000/µL |

1 |

> 25,000/µL |

2 |

|

Hemoglobin |

11 g/dL to 13.5 g/dL |

1 |

< 11 g/dL |

2 |

|

Sodium |

< 135 mmol/L |

2 |

Creatinine |

> 1.6 mg/dL |

2 |

Glucose |

> 180 mg/dL |

1 |

LRINEC: Laboratory Risk Indicator for Necrotizing Fasciitis |

||

The diagnosis of necrotizing soft tissue infection primarily is clinical, but imaging looking for gas in the subcutaneous tissue or along fascial planes can be helpful when the diagnosis is uncertain.28 Plain radiographs can detect gas in the soft tissue, but a CT scan is more sensitive, showing fat stranding, fluid and gas collections along fascial planes, and gas in the soft tissues.26,29

There are specific types of necrotizing skin and soft tissue infections based on location or microbiology.27 Three specific necrotizing infections are Fournier’s gangrene, gas gangrene, and water-/soil-borne necrotizing infections.

Fournier’s gangrene is a severe necrotizing skin and soft tissue infection of the genital area or perineum.26 Infection often occurs from anorectal, genitourinary, or local cutaneous sources. Patients present with swelling, erythema, and severe pain out of proportion in the genital area or perineum. The Fournier’s Gangrene Severity Index (FGSI) provides a tool for predicting outcome in patients with Fournier’s gangrene. Factors included in the FGSI are temperature, heart rate, respiration rate, sodium, potassium, creatinine, leukocytes, hematocrit, and bicarbonate on admission. A score above 9 has been noted to be sensitive and specific as a mortality predictor.26

Gas gangrene is a necrotizing infection of skeletal muscle caused by Clostridium spp. Clostridium perfringens causes 80% to 90% of gas gangrene cases. Clostridium spp. are found in the soil and organic waste, especially if it is contaminated with fecal material.30 Gas gangrene usually is found in skin and skeletal muscle that have experienced trauma or, less commonly, can occur spontaneously in uninjured muscle.

Gas gangrene starts with severe pain within 24 hours at the site of injury. Initially, the skin will be pale and then quickly change to bronze and then a purplish-red color.1 The skin becomes tense and tender with bullae. Lastly, the patient will have crepitus at the site of infection indicating gas being released by the organism in the tissue. Patients also may have systemic symptoms, including tachycardia, fever, and diaphoresis.26

Water-borne necrotizing infections are caused by Vibrio spp. The most common cause is Vibrio vulnificus, which can be found in warm coastal waters. These infections are caused through the exposure of traumatic wounds to seawater or seafood, or hematogenous seeding through primary bacteremia that occurs through ingestion of contaminated seafood. Water-borne necrotizing infections present with ecchymosis and hemorrhagic bullae of the skin.30

Management and Complications

Around the Hair Follicle

Folliculitis frequently is caused by S. aureus, both methicillin-sensitive and methicillin-resistant varieties. Another type of folliculitis is “hot tub folliculitis,” which is caused by Pseudomonas and, as implied by the name, frequently occurs after exposure to hot tubs. Folliculitis often resolves spontaneously within a few days and does not require treatment, but topical antibiotics can be used.12

Furuncles can rupture and drain spontaneously or may drain spontaneously following treatment with moist heat.13 Larger furuncles and all carbuncles should be treated with incision and drainage.10 If a surrounding cellulitis is present or systemic symptoms such as fever are present, the infection also should be treated with oral antibiotics.13

Infections of the Skin

Impetigo is caused most commonly by gram-positive bacteria. Eighty percent of non-bullous impetigo cases are caused by S. aureus, 10% are caused by group A beta-hemolytic strep, and the last 10% are caused by a combination. Bullous impetigo is caused most often by S. aureus.

Treatment of impetigo includes topical or oral antibiotics and symptomatic care. Localized, uncomplicated, and non-bullous infections can be treated with topical antibiotics such as mupirocin or retapamulin.31 Bullous, non-bullous with more than five lesions, deep tissue involvement, systemic signs, lymphadenopathy, and lesions in the oral cavity all are indications for treatment with systemic antibiotics. Impetigo can be self-limiting, but antibiotics decrease the duration of illness and spread of the lesions.

Regimens can include dicloxacillin or cephalexin for a duration of seven days. If MRSA is suspected, coverage should be broadened.31 Antibiotics also decrease the chance of involvement of the kidneys, joints, bones, lungs, and acute rheumatic fever. Antibiotics do not decrease the incidence of post-streptococcus glomerulonephritis.14 Post-streptococcus glomerulonephritis occurs in approximately 5% of patients infected with Streptococcus and occurs two to three weeks after skin infection.

The most common cause of erysipelas is group A Streptococcus.15 Most infections of the face are due to group A Streptococcus, and non-group A Streptococcus infections are more common on the lower extremities.15 Erysipelas rarely is caused by Staphylococcus aureus.15 Treatment is oral antibiotics for five days.9,15 If symptoms are not improving, then oral antibiotics can be extended to 10 days.9,15 Patients who have evidence of necrotizing infection, immunocompromise, poor adherence to medication or poor follow up, or have failed outpatient oral antibiotics should be hospitalized.12

Cellulitis is caused most commonly by beta-hemolytic streptococci.16 Cellulitis also can be caused by S. aureus, especially if there is associated purulence or an abscess. Neutropenic and immunocompromised patients also are susceptible to gram-negative cellulitis.15

Patients can be treated outpatient if they are able to adhere to therapy and do not have general signs of systemic toxicity or hemodynamic instability. Patients should be treated with oral antibiotics for five days. Antibiotics should be extended to seven to 10 days if the infection has not fully resolved in five days. There is a risk of recurrence in the same location in patients with edema, venous insufficiency, prior trauma (including surgery), and tinea pedis.16

Special considerations need to be taken for cellulitis caused by human and animal bites. Wounds caused by bites should be irrigated and necrotic tissue should be debrided to prevent infection and decrease the incidence of invasive wound infection. Human and animal bite wounds should not undergo primary wound closure unless present on the face.

Prophylactic antibiotics for three to five days should be given for bite wounds to the face, wounds associated with a crush injury, preexisting or subsequent edema, wounds on the hands or in proximity to a bone or joint, or in an immunocompromised patient. A reasonable empiric regimen could include amoxicillin-clavulanate.31 All patients with a bite wound should receive tetanus prophylaxis.16 Treatment of cellulitis that develops due to a bite wound should be treated for five days and extended to seven to 10 days if there is no improvement of the infection at day 5 of antibiotics.16

Special Types of Cellulitis

Periorbital cellulitis treatment is based on severity of disease and age of the patient.17 Patients with mild symptoms and older than 1 year of age can be treated as outpatients with oral antibiotics. Patients with severe disease or who are younger than 1 year of age should be admitted to the hospital.17 Treatment for periorbital cellulitis should cover S. aureus, Streptococcus spp., and anaerobes. Oral antibiotics should be prescribed for five to seven days.17 Oral antibiotics can be extended if cellulitis persists. If a patient fails to show improvement in 24 to 48 hours, then the patient should be hospitalized for broad-spectrum antibiotics.17

Orbital cellulitis is a serious and life-threatening infection. Empiric intravenous antibiotics should be initiated promptly. Empiric intravenous antibiotics should cover S. aureus (including MRSA), S. pneumoniae and other Streptococcus spp., and gram-negative bacilli.18 The most common causative organisms are Staphylococcus spp. and Streptococcus spp.18 Some patients may require surgical drainage.18,20 Complications include injury to the eye, or abscess behind or around the eye or in the bone. Infection can even extend intracranially leading to brain abscess, cavernous sinus thrombosis, and meningitis.18 If intracranial expansion is suspected, then anaerobic coverage should be included.

Ludwig’s angina is another serious and life-threatening soft tissue infection at risk of rapid spread.19 On initial evaluation, the patient’s airway and hemodynamic status should be assessed and the patient should be serially assessed for clinical changes. If the patient has evidence of significant airway swelling, dyspnea, stridor, cyanosis, or worsening airway symptoms on reevaluation, then the patient should be intubated emergently. The optimal technique for intubation in Ludwig’s angina is via awake nasotracheal intubation in the seated position using a flexible intubating endoscope.

Equipment for a surgical airway should be set up prior to the intubation attempt in case of failure of nasotracheal intubation. If time allows, otolaryngology and anesthesiology specialists should be emergently consulted for possible definitive airway management in the operating room. Mortality most often occurs due to airway compromise.19

The keys to treatment of Ludwig’s angina are broad-spectrum antibiotics and surgical source control. Patients should be started on broad-spectrum antibiotics, such as clindamycin, piperacillin-tazobactam, or ampicillin-sulbactam, that cover anaerobic, aerobic, and oral flora. Ludwig’s angina typically is caused by polymicrobial oral cavity flora. Viridans group streptococci are found in more than 40% of cases.16 Other common bacteria are S. aureus, S. epidermidis, Enterococcus spp., E. coli, Fusobacterium spp., Streptococcus spp., Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Actinomyces spp. If Ludwig’s angina stems from a dental infection, common bacteria are Actinomyces spp., Peptostreptococcus spp., Fusobacterium spp., and Bacteroides spp. If a patient is immunocompromised, they also are at high risk of gram-negative aerobic infections and MRSA.19

Corticosteroids (i.e., dexamethasone) should be used to reduce facial swelling and airway edema and improve antibiotic penetration. Nebulized epinephrine also can be used to reduce airway obstruction.18 If a patient does not respond to antibiotics, the patient will require liberal fasciotomy of deep cervical fascia of the submandibular region.10 Patients also will require surgery if there is the presence of fluctuance on exam or visible abscess on imaging. Patients should be admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU).

Complications of Ludwig’s angina include descending mediastinitis, necrotizing fasciitis of the neck and chest, pericarditis, carotid artery rupture, jugular vein thrombosis, pleural empyema, pneumonia, and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). Patients who are older than 65 years of age, have diabetes, have a history of alcohol use, or are immunocompromised are at highest risk for mortality.19

Abscess

Treatment of abscess includes a combination of incision and drainage in addition to antibiotic administration. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis showed the use of antibiotics for skin and soft tissue abscess after incision and drainage resulted in an increased clinical cure rate.32 Antibiotic selection for abscess should include MRSA coverage, such as doxycycline, clindamycin, or sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim.31

There are many different approaches to the bedside incision and drainage procedure for a simple abscess. A general approach to abscess drainage includes informed consent, skin cleansing, local anesthesia, incision, and cavity exploration.33 For complete drainage, consider an incision length just larger than the diameter of the abscess in parallel to the skin’s Langer lines. Irrigation and abscess cavity packing are controversial. The decision to pack the incision cavity may depend on provider preference or wound characteristics. Providers may consider loop drain placement or packing to keep the cavity open. Packing has been noted to increase pain associated with the wound and require follow-up encounters for packing removal and/or replacement. Outcomes with or without packing are similar.34

Loop drainage technique has been shown to be noninferior to traditional incision and drainage technique and consists of two stab incisions at the margins of the abscess with placement of a rubber drain through the wound to keep the cavity open and can later be cut and removed by the patient at home.35

Aspiration of an abscess has been shown to have significantly worse outcomes when compared to traditional incision and drainage.36

One also may consider use of bedside ultrasound in the diagnosis and treatment of skin and soft tissue abscess. The combination of ultrasound with incision and drainage has been shown to decrease failure rate.37 Ultrasound also can help the provider identify wound margins and identify ideal placement of the incision.

At discharge, patients should be instructed to keep the area clean and dry. If packing was placed, recommend follow up in one to three days for packing change and wound recheck. Home irrigation and/or sitz baths and follow up in five to seven days should be discussed.32 Recurrent abscesses should be investigated further.32 Recurrence is common when the abscess is due to pilonidal cyst or hidradenitis suppurativa, or from retained foreign material.13

Special Abscesses. Abscesses in specific areas of the body require unique considerations and treatment. Like abscesses of the skin, these abscesses primarily are a clinical diagnosis, but they sometimes can be evaluated further with ultrasound.20

Peritonsillar Abscess. A peritonsillar abscess is an abscess around a tonsil and often is a complication of tonsillitis. If the diagnosis is unclear, intraoral or transcutaneous cervical ultrasound can be used. Peritonsillar abscesses can be drained by either needle aspiration or incision and drainage. Studies have been inconclusive to determine whether needle aspiration or incision and drainage is more successful.

Peritonsillar abscesses often can be managed successfully with antibiotics and steroids, possibly reducing the need for invasive incision and drainage. Peritonsillar abscesses should be treated promptly to avoid complications, such as airway obstruction, aspiration of pus into the lungs, or spread of the infection into the deep neck.20

Dental Abscess. There are two types of dental abscesses: periapical and periodontal. A periapical abscess is an abscess present at the gum line. A periodontal abscess is a collection of pus at the pocket surrounding the tooth. Treatment of a dental abscess is incision and drainage. Research remains unclear if antibiotics are beneficial in treatment of a dental abscess.20 Dental referral and follow-up is appropriate.

Breast Abscess. There are two types of breast abscess: lactational breast abscess, which is a common complication of breastfeeding, and non-lactational breast abscess, which is less common. Treatment of a breast abscess that is less than 3 cm, both lactational and non-lactational, is needle aspiration. Breast abscesses that are 3 cm to 5 cm should undergo ultrasound-guided percutaneous drainage. Lastly, breast abscesses that are greater than 5 cm or include complicating factors should undergo incision and drainage.20

Bartholin Gland Abscess. Bartholin gland abscesses are formed by blockage of the Bartholin duct. Bartholin gland abscess treatment is incision and drainage with placement of a Word catheter.20

Pilonidal Abscess. A pilonidal abscess is an abscess of the skin of the gluteal cleft. A pilonidal abscess usually is the result of an embedded hair and commonly occurs in young adult men.19 Treatment of a pilonidal abscess is incision and drainage. Recurrence rates after incision and drainage are as low as 20%. Incision and drainage should be performed with an off-midline longitudinal incision, rather than a midline longitudinal incision, because the off-midline approach has demonstrated shorter healing times.3 Recurrent abscesses may require surgical management to remove the underlying sinus tract.20,38

Anorectal Abscess. There are two types of anorectal abscesses: perianal and perirectal.39 Perianal abscesses often are simple and superficial, and they make up approximately 60% of anorectal abscesses. Perirectal abscesses include deeper abscesses that are ischiorectal, supralevator, and intersphincteric.39 Diagnosis often is clinical and may require an exam under anesthesia.10 CT can be used to determine the extent of the infection.39 Approximately 10% of cases are associated with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), Crohn’s disease, trauma, tuberculosis, sexually transmitted diseases, radiation, foreign bodies, and malignancy.

Perianal abscesses can be treated with incision and drainage. Perirectal abscesses require IV antibiotics and surgical evaluation and drainage.39 Patients who are immunocompromised, have systemic signs of infection, have incomplete source control, fail to improve after drainage, or have significant abscess or surrounding area of cellulitis also should be treated with antibiotics.10,39 Antibiotics should be broad, covering for gram-positive, gram-negative, and anaerobic bacteria.10 Antibiotics should be given for five days and extended to seven to 10 days if the infection is not fully resolved after five days of antibiotics.10

Hidradenitis Suppurativa

Hidradenitis suppurativa is a chronic inflammatory disease that occurs in regions of skin that contain sweat glands.17 Hidradenitis suppurativa requires long-term management with medications, such as topical clindamycin, tetracyclines, and sometimes anti-anhydrogens in females.17 An acute abscess in the setting of hidradenitis suppurativa requires unique treatment from other abscesses. An acute abscess in the setting of hidradenitis suppurativa should be managed by surgical excision in the operating room.17 Incision and drainage is not recommended since this has a high incidence of recurrence.17 Wide surgical excision has the lowest recurrence rate.17 However, without availability of surgical management, incision and drainage can be used for pain relief and prevention of sepsis from the abscess.17

Infections of the Hand

Paronychia is most commonly caused by Staphylococcus spp.23 Treatment is oral antibiotics and warm soaks.23,24 If fluctuance is present indicating an abscess, then an incision and drainage should be performed by lifting the cuticle off the nail. If untreated, the infection can spread to the hand and involve underlying tendons.23

A felon in the early period of the infection and that does not have evidence of a drainable fluid collection can be treated with antibiotics and warm soaks.22 If there is evidence of a drainable fluid collection, then an incision and drainage should be performed. Antibiotics should be directed at treating Staphylococcus spp. and Streptococcus spp. because these are the most common causative organisms. If untreated, the infection can cause tissue necrosis of the finger pad or spread to cause osteomyelitis or pyogenic flexor tenosynovitis.23

Pyogenic flexor tenosynovitis should be treated aggressively. Patients should be treated with IV antibiotics, and a hand surgeon should be consulted immediately for possible surgery.23 Surgery often is required for evacuation of the infection, and intraoperative cultures should be obtained to tailor post-operative antibiotics. The most common cause of pyogenic flexor tenosynovitis is S. aureus in 80% of cases. Streptococcus spp. and Pseudomonas also are common causes.24

Necrotizing Skin and Soft Tissue Infections

Time is of the essence for management of necrotizing skin and soft tissue infections. Delay in diagnosis and treatment increases the risk of mortality, and imaging should not delay or deter surgery because early surgical debridement is essential to decrease mortality.10,40 The keys to treatment are antibiotics and surgery.26

Patients should be started on empiric antibiotics that cover gram-positive (including MRSA), gram-negative, and anaerobic organisms to start.10 Empiric antibiotic therapy could include vancomycin or linezolid plus piperacillin-tazobactam or a carbapenem or plus ceftriaxone and metronidazole.31

However, the mainstay of treatment is surgery.10 Surgical source control should be initiated within six hours.10,26 Patients who receive surgical treatment within six hours have a 19% mortality rate compared to 32% in patients whose surgery is delayed more than six hours.26 Cultures should be obtained, including post-operative cultures, to de-escalate antibiotic coverage.27

Patients should be reevaluated frequently after surgery or return to the operating room within 24 hours to ensure the initial debridement was adequate and there is no additional infection or tissue necrosis.27 Additional options for treatment are intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) in patients with Streptococcus necrotizing soft tissue infection and hyperbaric oxygen.10

Summary

Early diagnosis and treatment of severe infections decrease morbidity and mortality in addition to healthcare costs. It is important for the provider to understand the pathophysiology associated with the development of these infections and the recommendations for the specific treatment based on clinical presentation. Antibiotic selection should be catered to the most common causes of the specified infection in consideration for local resistance patterns. The provider must recognize SSTIs that require surgical management for source control and treatment.

References

- Watkins RR, David MZ. Approach to the patient with a skin and soft tissue infection. Infect Dis Clin North Am 2021;35:1-48.

- Menzin J, Marton JP, Meyers JL, et al. Inpatient treatment patterns, outcomes, and costs of skin and skin structure infections because of Staphylococcus aureus. Am J Infect Control 2010;38:44-49.

- Itani KM, Merchant S, Lin SJ, et al. Outcomes and management costs in patients hospitalized for skin and skin-structure infections. Am J Infect Control 2011;39:42-49.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. NAMCS/NHAMCS - Ambulatory Health Care Data. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Dec. 28, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/ahcd/index.htm

- Frazee BW, Lynn J, Charlebois ED, et al. High prevalence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in emergency department skin and soft tissue infections. Ann Emerg Med 2005;45:311-320.

- Moran GJ, Krishnadasan A, Gorwitz RJ, et al. Methicillin-resistant S. aureus infections among patients in the emergency department. N Engl J Med 2006;355:666-674.

- Albrecht VS, Limbago BM, Moran GJ, et al. Staphylococcus aureus colonization and strain type at various body sites among patients with a closed abscess and uninfected controls at U.S. emergency departments. J Clin Microbiol 2015;53:3478-3484.

- Miller LG, Diep BA. Clinical practice: Colonization, fomites, and virulence: Rethinking the pathogenesis of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection. Clin Infect Dis 2008;46:752-760.

- Stevens DL, Bryant AE. Impetigo, Erysipelas and Cellulitis. In: Streptococcus pyogenes: Basic Biology to Clinical Manifestations. University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center; 2016.

- Duane TM, Huston JM, Collom M, et al. Surgical Infection Society 2020 updated guidelines on the management of complicated skin and soft tissue infections. Surg Infect (Larchmt) 2021;22:383-399.

- Baiu I, Melendez E. Periorbital and orbital cellulitis. JAMA 2020;323:196.

- Winters RD, Mitchell M. Folliculitis. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Updated Aug. 8, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK547754/

- Lin HS, Lin PT, Tsai YS, et al. Interventions for bacterial folliculitis and boils (furuncles and carbuncles). Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2021;2:CD013099.

- Nardi NM, Schaefer TJ. Impetigo. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Oct. 19, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430974/

- Michael Y, Shaukat NM. Erysipelas. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Updated Aug. 9, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK532247/

- Rrapi R, Chand S, Kroshinsky D. Cellulitis: A review of pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management. Med Clin North Am 2021;105:723-735.

- Bae C, Bourget D. Periorbital Cellulitis. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Updated July 18, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470408/

- Danishyar A, Sergent SR. Orbital cellulitis. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Updated Aug. 8, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507901/

- Bridwell R, Gottlieb M, Koyfman A, Long B. Diagnosis and management of Ludwig’s angina: An evidence-based review. Am J Emerg Med 2021;41:1-5.

- Menegas S, Moayedi S, Torres M. Abscess management: An evidence-based review for emergency medicine clinicians. J Emerg Med 2021;60:310-320.

- Arnold MJ, Jonas CE, Carter RE. Point-of-care ultrasonography. Am Fam Physician 2020;101:275-285.

- Dulski A, Edwards CW. Paronychia. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan-. Updated Aug. 8, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK544307/

- Koshy J, Bell B. Hand infections. J Hand Surg Am 2019;44:46-54.

- Goyal K, Speeckaert AL. Pyogenic flexor tenosynovitis: Evaluation and management. Hand Clin 2020;36:323-329.

- Rerucha CM, Ewing JT, Oppenlander KE, Cowan WC. Acute hand infections. Am Fam Physician 2019;99:228-236.

- Sartelli M, Coccolini F, Kluger Y, et al. WSES/GAIS/WSIS/SIS-E/AAST global clinical pathways for patients with skin and soft tissue infections. World J Emerg Surg 2022;17:3.

- Peetermans M, de Prost N, Eckmann C, et al. Necrotizing skin and soft-tissue infections in the intensive care unit. Clin Microbiol Infect 2020;26:8-17.

- Goh T, Goh LG, Ang CH, Wong CH. Early diagnosis of necrotizing fasciitis. Br J Surg 2014;101:e119-e125.

- Fernando SM, Tran A, Cheng W, et al. Necrotizing soft tissue infection: Diagnostic accuracy of physical examination, imaging, and LRINEC score: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Surg 2019;269:58-65.

- Buboltz JB, Murphy-Lavoie HM. Gas gangrene. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Updated Jan. 30, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537030/

- Stevens D, Bisno AL, Chambers HF, et al. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft tissue infections: 2014 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 2014;59:e10-e52. https://www.idsociety.org/practice-guideline/skin-and-soft-tissue-infections/

- Gottlieb M, DeMott JM, Hallock M, Peksa GD. Systemic antibiotics for the treatment of skin and soft tissue abscesses: A systemic review and meta-analysis. Ann Emerg Med 2019;73:8-16.

- Aleksandrovskiy I, Caputo ND, Hosford K, Waseem M. Incision and drainage of abscess. In: Ganti L, ed. Atlas of Emergency Medicine Procedures. 2nd ed. Springer Nature Switzerland AG;2022:515-519.

- Mohamedahmed AYY, Zaman S, Stonelake S, et al. Incision and drainage of cutaneous abscess with or without cavity packing: A systemic review, meta-analysis, and trial sequential analysis of randomised controlled trials. Langenbecks Arch Surg 2021;406:981-991.

- Schechter-Perkins EM, Dwyer KH, Amin A, et al. Loop drainage is noninferior to traditional incision and drainage for cutaneous abscesses in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med 2020;27:1150-1157.

- Long B, Gottlieb M. Diagnosis and management of cellulitis and abscess in the emergency department setting: An evidence-based review. J Emerg Med 2022;62:16-27.

- Goulding M, Haran J, Sanseverino A, et al. Clinical failure in abscess treatment: The role of ultrasound and incision and drainage. CJEM 2022;24:39-43.

- Harries RL, Alqallaf A, Torkington J, Harding KG. Management of sacrococcygeal pilonidal sinus disease. Int Wound J 2019;16:370-378.

- Turner SV, Singh J. Perirectal abscess. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Updated Aug. 8, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507895/

- Nawijn F, Smeeing DPJ, Houwert RM, et al. Time is of the essence when treating necrotizing soft tissue infections: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Emerg Surg 2020;15:4.

Skin and soft tissue infections refer to infections that affect the skin and its underlying soft tissues. These infections are classified by the level of skin involvement. The costs associated with Staphylococcus aureus skin and soft tissue infections are estimated at an average of $8,865 for both inpatient and outpatient treatment, and a median charge of $19,984 for hospitalizations. These costs can place a significant burden on both patients and the healthcare system. Timely and accurate diagnosis and treatment can help to reduce this burden, both financially and by decreasing the risk of complications.

Subscribe Now for Access

You have reached your article limit for the month. We hope you found our articles both enjoyable and insightful. For information on new subscriptions, product trials, alternative billing arrangements or group and site discounts please call 800-688-2421. We look forward to having you as a long-term member of the Relias Media community.