Evaluation and Management of Angioedema in the Emergency Department

April 1, 2023

Related Articles

-

Infectious Disease Updates

-

Noninferiority of Seven vs. 14 Days of Antibiotic Therapy for Bloodstream Infections

-

Parvovirus and Increasing Danger in Pregnancy and Sickle Cell Disease

-

Oseltamivir for Adults Hospitalized with Influenza: Earlier Is Better

-

Usefulness of Pyuria to Diagnose UTI in Children

AUTHORS

Creagh Boulger, MD, FACEP, FAIUM, Associate Director, Division of Ultrasound, Professor, Department of Emergency Medicine, POCUS Fellowship Director, Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, Department

of Emergency Medicine, Columbus

Abigail Hecht, Medical Student, Ohio State University School of Medicine, Columbus

PEER REVIEWER

Steven M. Winograd, MD, FACEP, Attending Emergency Physician, Trinity Health Care, Samaritan, Troy, NY

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

- There are two pathways that lead to the presentation of angioedema. Histamine-mediated angioedema is more like a typical allergic reaction, but with swelling and less often urticaria. Bradykinin-mediated angioedema often is due to hereditary causes (although it can be acquired) or as a reaction to medication, most typically angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors.

- Although histamine-mediated angioedema usually is of rapid onset and progresses rapidly, bradykinin-mediated angioedema develops more slowly, over hours or even days. In addition, bradykinin-mediated angioedema is less likely to present with urticaria and more likely to present with acute abdominal pain.

- The treatment of histamine-mediated angioedema is based primarily on epinephrine, with adjuncts of steroids, antihistamines, and H1/H2 blockers. The treatment of bradykinin-mediated angioedema is based primarily on icatibant, ecallantide, or a C1 inhibitor.

- Airway obstruction with respiratory arrest is the most common cause of death during an episode of angioedema. Surgical airway may be needed. Preparation of a surgical airway should occur as quickly as possible, and ideally before orotracheal intubation is attempted.

Introduction

Angioedema is a condition that presents as painless, non-pitting edema in subcutaneous and submucosal tissues.1,2 The most commonly affected areas of the body are the face, oropharynx, and gastrointestinal tract.1-3 Unlike an allergic reaction, angioedema does not typically involve urticaria or other integument findings. The etiology of angioedema varies and has been associated most commonly with histamine- or bradykinin-mediated mechanisms.1,2,4 This diagnosis is relatively common, with a total lifetime prevalence between 10% and 25%.4-6 Patients who present to the emergency department with symptoms concerning for angioedema require rapid management, particularly in the setting of laryngeal edema.2,3 Thus, it is critical for emergency department physicians to develop the skills to promptly identify presentations of angioedema and appropriately select treatment based on these findings.4 This article examines the differences between various mechanisms of angioedema, reviews clinical presentations and diagnostic considerations, and discusses management techniques.

Case Introduction

A 45-year-old male presents to the emergency department with concern of allergic reaction. The patient states that about 15 minutes prior, his lips felt tight. He looked in the mirror and noticed marked swelling. The swelling has been getting worse over the course of the day. He also notes a sensation of fullness in his throat. He denies any new foods, stings, or exposures. The patient’s past medical history is significant for hypertension and diabetes. His vitals are: blood pressure 180/98 mmHg, heart rate 105 bpm, respiratory rate 14 breaths/minute, and SpO2 94% on room air.

Epidemiology

In the United States, approximately 100,000 emergency department visits each year are associated with angioedema.4 The etiology of angioedema, either histamine-mediated or bradykinin-mediated, plays a significant role in evaluating risk factors and selecting appropriate treatment. Histamine-mediated angioedema accounts for around 30% of angioedema episodes, with patients presenting at any age, and it often is associated with allergens or, more rarely, anaphylaxis.7,8 In contrast, bradykinin-mediated angioedema accounts for a different subset of patients, including hereditary, acquired, and medication-induced exacerbations.5,9

Hereditary angioedema is an autosomal dominant genetic disorder, affecting between one in 10,000 and one in 150,000 individuals. It is estimated to present with laryngeal edema in approximately 50% of exacerbations.1,2,10 Angioedema triggered by angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors is a more common form of bradykinin-mediated angioedema and comprises approximately 30% of overall cases of angioedema.11 ACE-inhibitor-induced angioedema can present at any time during a patient’s course of medication. Without appropriate treatment, the mortality rate of bradykinin-mediated angioedema is approximately 30%; thus, it is essential that patients presenting with angioedema receive rapid assessment and treatment.5

Pathophysiology

Histamine-Mediated Angioedema

One proposed mechanism of angioedema is through a histamine-mediated pathway, in which mast cell degranulation occurs through a type 1 hypersensitivity reaction.9,12 (See Table 1.) This functions in the same manner as a traditional allergic reaction, where an allergen is taken up by antigen-presenting cells and broken up into smaller peptides.9 During this stage, known as the sensitization stage, these peptides then are expressed on the cell surface and presented to CD4-positive cells, or helper T cells, which results in T-cell activation.9,13 These T cells then release Th2 cytokines, which promote B-cell production of immunoglobulin E (IgE) antibodies.13 Once these antibodies are produced and re-exposed to the inciting antigen, degranulation of mast cells and basophils will occur, resulting in release of preformed inflammatory mediators.9,13 These inflammatory mediators, which include histamine, subsequently cause vasodilation, increased vascular permeability, and tissue damage, which ultimately can manifest as angioedema when fluid shifts from the intravascular to the interstitial space.9,13

Table 1. Types of Hypersensitivity Reactions |

||||

Type 1 |

Type 2 |

Type 3 |

Type 4 |

|

Mediator |

IgE |

IgG and IgM |

Immune complex |

T cell |

Onset |

Immediate |

Hours to days |

Weeks |

Days to weeks |

Examples |

Bee stings, latex |

Hemolytic, Goodpasture syndrome |

Serum sickness, SLE |

Stevens Johnson syndrome, graft rejection, PPD test |

Descriptor |

Allergic |

Cytotoxic |

Immune |

Delayed |

IgE: immunoglobulin E; IgG: immunoglobulin G; IgM: immunoglobulin M; SLE: systemic lupus erythematosus; PPD: purified protein derivative |

||||

This mechanism is largely associated with allergic reactions and/or anaphylaxis, depending on the severity of presentation, and occurs quickly upon exposures to the antigen. Other mechanisms of histamine-mediated angioedema include direct activation of mast cells or basophils without IgE, with potential triggers including opiates, intravenous (IV) contrast, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), or other iatrogenic sources.5,12

Bradykinin-Mediated Angioedema

Bradykinin-mediated angioedema is thought to be either hereditary or acquired and is associated with kallikrein-kinin cascade activation and/or decreased bradykinin degradation.5,12 Bradykinin is produced via the kallikrein-kinin cascade, when plasma kallikrein breaks down high molecular-weight kininogen.14 This molecule then binds bradykinin 2 receptors and mediates a variety of pro-inflammatory functions, including vasodilation, increased vascular permeability, and increased pain.12,14 This system, known as the contact activating system (CAS), is a defense mechanism against foreign proteins and organisms. Regulation of this system occurs through the C1 esterase inhibitor, a regulatory protein that prevents unrestricted activation of the cascade, and kininase II, an enzyme that helps inactivate bradykinin.12,14 In bradykinin-mediated angioedema, this regulation is disrupted either through a deficiency of the C1 esterase inhibitor, abnormal C1 esterase, or consumption of the C1 esterase.

Angioedema through this pathway is mediated through three main mechanisms: hereditary angioedema, acquired angioedema, and iatrogenic angioedema, the most common of which is angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor-induced angioedema.5,9 Idiopathic and pseudoallergic angioedema also are thought to fall into this subclass of non-allergic angioedema. Their exact mechanism is unknown and could be secondary to bradykinin, leukotrienes, or other inflammatory substances.

Hereditary angioedema is a rare genetic disorder that involves the C1 esterase inhibitor protein and can be categorized into three different classes.9 Hereditary angioedema with deficient C1 inhibitor, or type I hereditary angioedema, involves decreased C1 esterase inhibitor levels due to a genetic mutation in the SERPING1 gene, which produces misfolded or shortened proteins.5,12,15 Type II, or hereditary angioedema with dysfunctional C1 inhibitor, works in a similar way, where mutations in the SERPING1 gene result in proteins that are able to be secreted but their function is reduced.5,15 Type III, or hereditary angioedema with normal C1 inhibitor, occurs in the context of appropriate C1 esterase inhibitor levels and function, and, although the etiology is not entirely known, may involve dysfunction of Factor XII.12,15,16

Acquired angioedema is a rare form of C1 esterase inhibitor dysfunction that is associated with various disorders and is not localized to a certain genetic mutation or family history.5,17 This mechanism relates to either increased catabolism of C1 esterase inhibitor, typically as a result of an autoimmune disorder or lymphoproliferative disorder.9,17,18 Another form of acquired angioedema involves the development of an autoantibody to C1 esterase inhibitor and can occur independently or in conjunction with increased catabolism.5,18

Finally, medication-induced angioedema, specifically from an ACE inhibitor, ultimately results in increased levels of bradykinin through reduced catabolism.9 Normally, kininase II, another name for ACE, functions to inactivate and digest bradykinin; however, other enzymes, including aminopeptidase P, can regulate bradykinin levels when ACE is inhibited.19 In the setting of aminopeptidase P dysfunction, use of an ACE inhibitor blocks regulation of bradykinin and can result in development of angioedema.12,19 ACE-inhibitor angioedema has a high prevalence among African Americans as part of its genetic etiology.9

Presentation

Signs and Symptoms

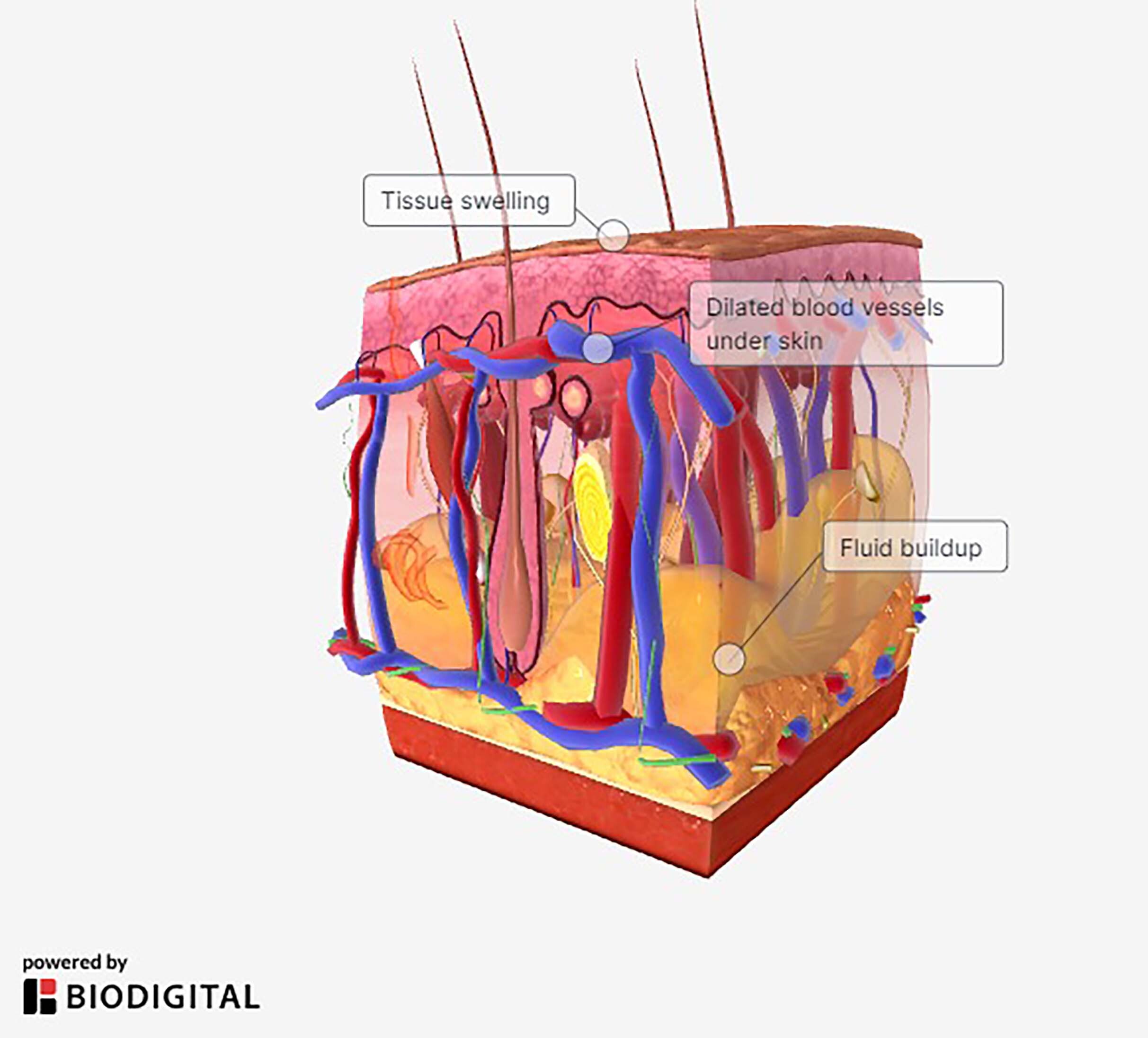

Angioedema generally presents as non-pitting edema of subcutaneous tissue and mucous membranes, although the time course and associated symptoms may vary depending on the etiology.1,2,5 (See Figure 1.) It is vital to recognize the risk for airway compromise in the setting of swelling in the tongue, pharynx, and/or larynx.3 (See Figures 2-5.) Given that asphyxiation is the primary cause of mortality in patients presenting with angioedema, reassessment of the airway must be performed frequently.20,21

Figure 1. Angioedema |

|

Figure 2. Angioedema of the Periorbital Face |

|

Source: Image used with permission from J. Stephan Stapczynski, MD. |

Figure 3. Angioedema of the Soft Palate and Uvula |

|

Source: Image used with permission from J. Stephan Stapczynski, MD. |

Figure 4. Angioedema of the Tongue |

|

Source: Image used with permission from J. Stephan Stapczynski, MD. |

Figure 5. Angioedema of the Tongue After Intubation |

|

Source: Image used with permission from J. Stephan Stapczynski, MD. |

The progression of histamine-mediated angioedema typically is rapid, peaking between 30 and 90 minutes, and often is associated with exposure to an allergen, such as food, drugs, stings, or other contact.1,5 Swelling commonly is localized to the face and larynx and may be accompanied with urticaria or hives in as much as 50% of cases.9,12 Anaphylaxis is a possible complication of this reaction, with associated symptoms including hypotension, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and respiratory distress.12 Additionally, in the absence of clear allergy, medications such as NSAIDs, opiates, and intravenous contrast are known to trigger histamine-mediated angioedema in some patients.5,8 Typically, angioedema triggered via this pathway resolves between 12 and 48 hours.8,12

In contrast, bradykinin-mediated angioedema often develops over a longer period of time, from several hours to days.8 Patients commonly present with laryngeal edema, non-pitting edema in the extremities, and abdominal pain from angioedema of the intestinal walls.11 The associated abdominal involvement, particularly in patients with hereditary angioedema, can be confused for acute abdomen.11,18 (See Table 2.) Urticaria, or a pruritic rash, is a less common presentation in this form of angioedema but does not rule out bradykinin-mediated pathology.8 In the setting of hereditary angioedema, erythema marginatum, a nonpruritic rash, may present several hours prior to an acute attack.1,8 Bradykinin-mediated angioedema may be recurrent, depending on etiology, and symptoms may last several days past the initial presentation.9,21

Table 2. Types of Angioedema, Mechanisms, Symptoms, and Treatments |

||

Type |

Symptoms |

Treatments |

Histamine-mediated |

|

|

Bradykinin-mediated |

|

|

Diagnostic Tools

For all forms of angioedema, obtaining a careful history and physical exam is key to differentiating between histamine-mediated and bradykinin-mediated pathophysiology and will help guide treatment strategies.12 However, any evidence of airway compromise or respiratory distress should be treated urgently to prevent mortality.20

For histamine-mediated angioedema, focusing on potential exposures is a key component of diagnosis.12 Potential antigens include foods, drugs, contact with insects, contrast agents, pollen or environmental allergens, anesthesia, etc.12 A detailed history of medical diagnoses, known allergies, and medication use should be gathered, along with a family history to rule out possible hereditary angioedema.12 In some cases, this may be a new allergy, and the patient may not have had a reaction to the substance in the past. Where there are many potential suspects, have the patient record all potential allergens (such as in a meal) so that any subsequent reaction can be cross-referenced. In the setting of an identifiable allergen or trigger, further diagnostic testing in the emergency department may not be warranted. Moreover, effective symptom response to antihistamine, corticosteroid, or epinephrine therapies is highly suggestive of a histamine-mediated mechanism.4,9 (See Table 3.)

Table 3. Summary of Evaluation of Angioedema |

Histamine-Mediated

Bradykinin-Mediated

|

Similarly, in bradykinin-mediated angioedema, diagnosis and differentiation is primarily clinical. Prior medical history should be collected, particularly regarding known angioedema episodes, previous diagnosis of hereditary angioedema, family history of similar symptoms, history of autoimmune disease, history of malignancy or lymphoproliferative disorder, and medication changes.8,21 Information regarding potential triggers should be collected and includes increased stress, minor trauma/injury, physical exertion, recent illness, foods, drugs, recent surgery, injections, or any notable shifts in daily routine or health.8 Providers should specifically query about medications, such as ACE inhibitors, angiotensin-II receptor blockers, NSAIDs, gliptins, sacubitril, estrogen, tissue plasminogen activator therapy, and antibiotics, because of their known risks of triggering bradykinin-mediated angioedema.11 In particular, use of ACE-inhibitor therapy has between a 0.1% and 0.7% risk of triggering an acute attack of angioedema, regardless of the duration of use.4,11,22

If the presenting patient has a known history of hereditary or acquired angioedema or a likely bradykinin trigger is identified, treatment should proceed targeting the bradykinin-mediated pathway. If the presenting patient has no prior history or obvious trigger of angioedema, a trial of antihistamines, corticosteroids, and/or epinephrine should be initiated. A poor response indicates that the mechanism likely is mediated by bradykinin.20 Laboratory evaluation of C1-esterase inhibitor levels, C1-esterase inhibitor function, and C4 should be obtained, since they may assist with long-term diagnosis and differentiation; however, these laboratory results may take several days and, thus, may or may not be available during the acute emergency department course.4,21 Not everything that looks like angioedema actually is angioedema. Please see Table 4 for a differential diagnosis.

Table 4. Differential Diagnosis of Angioedema: Pseudoangioedema |

|

Disease |

Clinical Clues to Differentiate from Angioedema |

Facial cellulitis |

|

Acute contact: allergic or photodermatitis |

|

Crohn’s disease of mouth and lips |

|

Hypocomplementemic urticarial vasculitis syndrome (HUVS) |

|

Dermatomyositis, systemic lupus erythematosus, polymyositis, Sjögren’s syndrome |

|

Hydrostatic edema |

|

Tumid discoid lupus |

|

Ascher syndrome |

|

Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome |

|

Superior vena cava syndrome |

|

Gleich syndrome: episodic angioedema with eosinophilia |

|

Schnitzler’s syndrome: macroglobulinemia secondary to monoclonal IgM |

|

Muckle-Wells syndrome |

|

Cheilitis granulomatosa/Miecher’s cheilitis |

|

Hypothyroidism |

|

Trichinosis |

|

Filarial parasites |

|

Facial lymphedema |

|

Oncotic edema |

|

Sources: Kaplan AP, Greaves MW. Angioedema. J Am Acad Dermatol 2005;53:373–88. quiz 389-392. Van Dellen RG, Maddox DE, Dutta EJ. Masqueraders of angioedema and urticaria. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2002;88:10. Gleich GJ, Schroeter AL, Marcoux JP, et al. Episodic angioedema associated with eosinophilia. N Engl J Med 1984;310:1621. Jara LJ, Navarro C, Medina G, et al. Hypocomplementemic urticarial vasculitis syndrome. Curr Rheumatol Rep 2009;11:410. Charlesworth EN. Differential diagnosis of angioedema. Allergy Asthma Proc 2002;23:337. Reprinted from: Fischer D, Abukhdeir HF. Understanding and managing angioedema in the emergency department. Emerg Med Rep 2016,37:269-284. |

|

Treatment and Disposition

Treatment of angioedema always should start with initial airway assessment and management, followed by supportive care and therapeutic intervention based on further evaluation.9 If there is any suspicion of laryngeal edema, nasotracheal intubation is advised; if unsuccessful, a surgical airway likely is indicated and should be prepared for prior to any intubation attempts.9

For suspected histamine-mediated angioedema, any causative agent should be discontinued, particularly NSAIDs, opiates, or other triggering medications.12 Treatment with oral steroids and antihistamine therapy should be initiated, with dual H1 and H2 blockade more effective than either one alone.9,12 If there are any signs of anaphylaxis, intramuscular epinephrine should be administered immediately.9,12 Close monitoring of vital signs, airway status, and symptom response to treatment is key to assessing the need for further intervention.4,5

Upon observation for several hours and significant improvement of symptoms, patients may be discharged with intramuscular epinephrine and outpatient follow-up with a primary care provider and/or allergist.4 Indications for admission include significant airway involvement, persistence of moderate to severe symptoms, unstable vital signs, or high suspicion for further complication.4,12

After airway assessment and management, the source of acute attacks for bradykinin-mediated angioedema guides treatment modalities. For hereditary angioedema, there are several treatment options that are shown to provide benefit in the setting of an acute attack.20 Various forms of C1-esterase inhibitor concentrate have been developed and approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for either treatment of hereditary angioedema exacerbations or prophylaxis.11,20 Icatibant, a bradykinin B2 receptor antagonist, and ecallantide, a kallikrein inhibitor, also are studied and approved to treat acute attacks.11,21,23 These therapies are shown to function best when administered early after symptom development.23

Fresh frozen plasma (FFP) can be used when other therapies are unavailable, but there is limited evidence of efficacy.20,21 Regardless, hypersensitivity reactions to any of the discussed treatment modalities are possible, thus patients should be monitored closely during and after administration.9 Previously, tranexamic acid (TXA) has been used to treat hereditary angioedema, although analyses have shown minimal efficacy when compared with C1-inhibitor concentrates, icatibant, and ecallantide.15,24 Androgens also have been trialed to trigger production of C1 inhibitor and may be helpful as prophylaxis, but they are not shown to effectively treat ongoing exacerbations. Moreover, side effects of these medications often preclude long-term clinical use.15

Treatment of acquired angioedema is based on very limited data and focuses on management of the underlying cause as well as use of plasma-derived C1-inhibitor concentrate.17,18 Some patients may develop tolerance to C1-inhibitor therapy, in which case icatibant or ecallantide should be tried.17 As an alternative therapy, FFP could be used; however, efficacy is not well-established.17

For ACE-inhibitor-triggered angioedema, discontinuing the medication and providing supportive care are the primary strategies for symptom resolution.22 Antihistamines and glucocorticoids may be tried, particularly if there is any uncertainty surrounding the diagnosis, but they likely will have little efficacy in true bradykinin-mediated angioedema.19,25 Unfortunately, there are no targeted therapies approved for treatment of ACE-inhibitor-induced angioedema; however, a few reports suggest that medications used to treat hereditary angioedema may be successful, including C1-inhibitor concentrate, icatibant, ecallantide, and FFP.25-27 Small studies and case reports suggest that use of TXA may reduce the need for intubation in ACE-inhibitor-induced angioedema, but further investigation is needed.28

Airway Management

Given the potential for airway compromise in patients presenting with possible angioedema, intubation should be considered early in the emergency department course.9 First, if it is suspected that an airway intervention may be required, it is necessary to act early, given the difficulty of intubation in the setting of significant laryngeal edema.9 Awake intubation is a consideration in this patient population; however, rapid sequence intubation (RSI) medications should be prepared and accessible in case of abrupt airway compromise.9 A short-acting paralytic, such as rocuronium or succinylcholine, is the best choice as long as there are no contraindications.29 Providers should consider the risks and benefits of various sedatives, including etomidate, ketamine, midazolam, and propofol, and select accordingly.29

Direct laryngoscopy or video laryngoscopy with endotracheal intubation is the initial preferred method, although in the setting of extensive edema, a nasal approach may be necessary. If an orotracheal or nasotracheal approach is unsuccessful, a surgical airway may be necessary.9,29 The provider should assess neck anatomy as early as possible and consider marking landmarks prior to any intubation attempts, since this population is at high risk for conversion to surgical airway secondary to edema and subsequently distorted anatomy.

Steroids and Antihistamines

Many clinicians discourage the use of steroids and antihistamines in patients with angioedema because they are not useful in bradykinin-mediated reactions. While this is mostly true in the emergent setting, it often is difficult or impossible to discern the etiology of the angioedema. Given this fact, there is little harm in giving steroids and antihistamines to the patient with angioedema. Additionally, histamine-mediated angioedema is more common and, thus, treatment with standard measures such as steroids, antihistamines, and epinephrine is prudent when the cause is unknown. (See Table 5.) If these treatments are ineffective, bradykinin-specific treatments can be initiated.

Table 5. Angioedema Treatments |

|||

Medication |

Indication |

Cost in the United States |

Time to Onset |

Steroids |

Histamine-induced or unknown |

$ |

|

Antihistamine |

Histamine-induced or unknown |

$ |

|

Epinephrine |

Histamine-induced or unknown |

$ |

|

Tranexamic acid |

Hereditary Drug-induced |

$ |

|

Fresh frozen plasma |

Hereditary Drug-induced |

$$ |

|

C1 inhibitor |

Drug-induced* Hereditary |

$$ |

|

Ecallantide |

Drug-induced |

$$$ |

|

Icatibant |

Drug-induced |

$$$ |

|

* In the systematic review, in all patients with drug-induced angioedema who received C1 inhibitors, all but one patient avoided an advanced airway.20 $ = $100 or less; $$ = thousands; $$$ = tens of thousands |

|||

Typical regimens include methylprednisolone, H1 blockade, and H2 blockade. Methylprednisolone should be given IV 1 mg/kg to 2 mg/kg, with a maximum dose of 125 mg. For H1 blockade, IV ranitidine can be used at a dose of 1 mg/kg, with a maximum of 50 mg. Similarly, diphenhydramine can be given IV 1 mg/kg with a max dose of 50 mg for H2 blockade.

Epinephrine

Although it is a mainstay of treatment for most suspected allergic reactions with airway compromise, the role of epinephrine in bradykinin-mediated angioedema has been debated. Epinephrine acts as an alpha and beta agonist. As a result, it causes vasoconstriction and bronchodilation. Given the mechanism of action and the fact that vasodilation is a source of edema in both mechanisms of angioedema, epinephrine likely will provide some benefit regardless of etiology. Epinephrine should be given intramuscular in a 1:1,000 concentration. The dosing is 0.01 mg/kg, with a typical adult dose being 0.3 mg to 0.5 mg and not exceeding 0.5 mg per single dose. Dosing can be repeated every five minutes as needed.

C1 Inhibitor

C1 esterase inhibitor replacement is one of the newest treatments for non-histamine-mediated angioedema in the United States; however, this drug class has been used in Europe for decades.20 These medications are given IV at 20 units per kg. Different from the kallikrein and bradykinin inhibitors, the cost is much less of an issue with this class of medication. The typical cost is in the low thousands of dollars per dose. The most commonly reported side effect with this medication is headache.

Ecallantide

Ecallantide is a kallikrein inhibitor, serving to prevent the production of bradykinin from high-molecular-weight kininogen.23 Patients typically receive this therapy as a 30-mg subcutaneous dose, although it may be repeated if symptoms persist.9,23 In various studies, this therapy has been proven to improve time to significant symptom reduction during acute attacks of hereditary angioedema.30,31 Efficacy was shown for treatment of moderate to severe attacks in all symptom locations.23,31 Serious hypersensitivity reactions, such as anaphylaxis, are considered the primary risk factor, but they are shown to occur in less than 3% of the study population.9,23

Icatibant

Icatibant is a relatively new treatment for angioedema. This drug is a bradykinin receptor blocker and, thus, is only indicated when bradykinin-mediated angioedema is suspected. Given that this medication is new, it is costly; however, the cost has been decreasing over the years in the United States. For some institutions, the cost still may be prohibitive, and this medication may not be available. Some studies show no difference in time to resolution between icatibant and placebo. Others, however, show resolution of symptoms in 15 minutes.32,33 The dosing of icatibant is 30 mg injected subcutaneously. Of note, transaminitis and fever can be seen with this injection and should be monitored.

Fresh Frozen Plasma

FFP can be administered in cases of angioedema. It works through replacement of C1 inhibitors that are present in the plasma and are dysfunctional in the patient. Because it is given to replace or overcome the patient’s dysfunctional inhibitors, large volumes typically have to be administered.34 Most studies start with 2-4 units, but they often require redosing. Unlike some of the other treatments, FFP can take hours to have effects. Additionally, since this is a transfusion, patients are at risk for transfusion reactions.

Tranexamic Acid

TXA typically is given for bleeding emergencies. This drug works by inhibiting the breakdown of plasminogen to plasmin. While it is true that this is part of clot stabilization, it also is part of the CAS and, thus, part of the cascade in bradykinin-mediated angioedema. Most of the literature on TXA looks at it as a prophylactic agent for hereditary angioedema. There are some small studies that suggest its use in the acute setting.35,36 Most studies looked at giving 1 g of TXA IV. Larger studies are needed to determine its overall efficacy; however, given that TXA is a very affordable medication and is relatively well tolerated, it seems worthwhile in this potentially life-threatening condition.

Disposition for patients with bradykinin-mediated angioedema is based primarily on airway status, although careful assessment of symptom progression is essential.11 Typically, symptoms can take up to a week to fully resolve. Admission is recommended if a patient demonstrates airway obstruction, edema in more than three locations, or hemodynamic instability.11 Patients experiencing mild symptoms without evidence of airway obstruction can be discharged after several hours of observation.4,11 Known triggers, such as ACE inhibitors, should be discontinued, and close follow-up with the patient’s primary care provider is recommended.4 If the patient has a known or suspected diagnosis of hereditary or acquired angioedema, it is important to establish follow-up with an immunologist.11 Clinicians should consider discharging patients with suspected histamine-mediated angioedema with a prescription for self-administered epinephrine.

Summary

Angioedema primarily presents as edema in subcutaneous and mucosal tissue, most commonly in the face, neck, and extremities.1 Life-threatening complications, such as laryngeal edema, are common; thus, rapid recognition and management are vital to avoid mortality.20 In addition, appropriate identification of the likely etiology of angioedema is key to selecting effective treatment.9

Histamine-mediated angioedema, typically associated with allergic reactions, often presents with urticaria and an identifiable trigger; management with antihistamine therapy, oral corticosteroids, and/or epinephrine should support resolution of symptoms.9,12 In contrast, features more unique to bradykinin-mediated angioedema include erythema marginatum, intestinal wall edema, genetic mutation, autoimmune disease history, lymphoproliferative disorder, and ACE inhibitor use.8,11 Management of this type of angioedema involves discontinuing possible triggers (i.e., ACE inhibitors), providing supportive care, and initiating targeted therapy (C1 esterase inhibitor concentrate, icatibant, or ecallantide).11,22 Regardless of etiology, any signs of airway compromise should be addressed immediately with nasotracheal intubation or surgical airway to prevent mortality.9,20 Disposition is predominantly based on airway stability; however, after the acute exacerbation of angioedema resolves, follow-up with a primary care provider and/or immunologist is advised for further work-up.11

Case Conclusion

A 45-year-old male presents to the emergency department with concern of allergic reaction. The patient states that about 15 minutes prior, his lips felt tight. He looked in the mirror and noticed marked swelling. The swelling has been getting worse. He also notes a sensation of fullness in his throat. He denies any new foods, stings, or exposures. The patient’s past medical history is significant for hypertension and diabetes. His vitals are: blood pressure 180/98 mmHg, heart rate 105 bpm, respiratory rate 14 breaths/minute, and SpO2 94% on room air.

In this patient, the clinician should have a high concern for airway compromise. Currently the patient is hemodynamically stable. The clinician should prepare to secure the airway. Simultaneously, they should administer IV diphenhydramine, methylprednisolone, and intramuscular epinephrine. Because this patient has a history of hypertension, the provider should attempt to get a medication list. If ACE inhibitors are on the list, bradykinin-mediated angioedema should be considered. If available, the provider can consider administering C1 inhibitor or second-line icatibant or ecallintide. If neither is available, FFP can be administered, although the provider should consider earlier airway intervention since the time to onset of FFP is more delayed. Given the severity of symptoms, this patient should be admitted for observation and monitoring until symptoms improve.

REFERENCES

- Memon RJ, Tiwari V. Angioedema. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

- Misra L, Khurmi N, Trentman TL. Angioedema: Classification, management and emerging therapies for the perioperative physician. Indian J Anaesth 2016;60:534-541.

- Kaplan AP. Angioedema. World Allergy Organ J 2008;1:103-113.

- Bernstein JA, Cremonesi P, Hoffmann TK, Hollingsworth J. Angioedema in the emergency department: A practical guide to differential diagnosis and management. Int J Emerg Med 2017;10:15.

- Tachdjian R, Johnston DT. Angioedema: Differential diagnosis and acute management. Postgrad Med 2021;133:765-770.

- Lewis LM. Angioedema: Etiology, pathophysiology, current and emerging therapies. J Emerg Med 2013;45:789-796.

- Marcelino-Rodriguez I, Callero A, Mendoza-Alvarez A, et al. Bradykinin-mediated angioedema: An update of the genetic causes and the impact of genomics. Front Genet 2019;10:900.

- Maurer M, Magerl M. Differences and similarities in the mechanisms and clinical expression of bradykinin-mediated vs. mast cell-mediated angioedema. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 2021;61:40-49.

- Bernstein JA, Moellman J. Emerging concepts in the diagnosis and treatment of patients with undifferentiated angioedema. Int J Emerg Med 2012;5:39.

- Lumry WR. Overview of epidemiology, pathophysiology, and disease progression in hereditary angioedema. Am J Manag Care 2013;19(7 Suppl):s103-s110.

- Long BJ, Koyfman A, Gottlieb M. Evaluation and management of angioedema in the emergency department. West J Emerg Med 2019;20:587-600.

- James C, Bernstein JA. Current and future therapies for the treatment of histamine-induced angioedema. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2017;18:253-262.

- Abbas M, Moussa M, Akel H. Type I hypersensitivity reaction. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

- Pirahanchi Y, Sharma S. Physiology, bradykinin. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

- Abdulkarim A, Craig TJ. Hereditary angioedema. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

- Miranda AR, de Ue APF, Sabbag DV, et al. Hereditary angioedema type III (estrogen-dependent) report of three cases and literature review. An Bras Dermatol 2013;88:578-584.

- Cicardi M, Zanichelli A. Acquired angioedema. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol 2010;6:14.

- Swanson TJ, Patel BC. Acquired angioedema. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

- Brown T, Gonzalez J, Monteleone C. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor-induced angioedema: A review of the literature. J Clin Hypertens 2017;19:1377-1382.

- Hébert J, Boursiquot JN, Chapdelaine H, et al. Bradykinin-induced angioedema in the emergency department. Int J Emerg Med 2022;15:15.

- Pines JM, Poarch K, Hughes S. Recognition and differential diagnosis of hereditary angioedema in the emergency department. J Emerg Med 2021;60:35-43.

- Garcia-Saucedo JC, Trejo-Gutierrez JF, Volcheck GW, et al. Incidence and risk factors of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor-induced angioedema: A large case-control study. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2021;127:591-5929.

- Cicardi M, Bork K, Caballero T, et al. Evidence-based recommendations for the therapeutic management of angioedema owing to hereditary C1 inhibitor deficiency: Consensus report of an International Working Group. Allergy 2012;67:147-157.

- Horiuchi T, Hide M, Yamashita K, Ohsawa I. The use of tranexamic acid for on-demand and prophylactic treatment of hereditary angioedema—A systematic review. J Cutaneous Immunol Allergy 2018;1:126-138.

- Erickson DL, Coop CA. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor-associated angioedema treated with c1-esterase inhibitor: A case report and review of the literature. Allergy Rhinol 2016;7:168-171.

- Howarth D. ACE inhibitor angioedema: A very late presentation. Aust Fam Physician 2013;42:860-862.

- Baş M, Greve J, Stelter K, et al. A randomized trial of icatibant in ACE-inhibitor–induced angioedema. N Engl J Med 2015;372:418-425.

- Hasara S, Wilson K, Amatea J, Anderson J. Tranexamic acid for the emergency treatment of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor-induced angioedema. Cureus 2021;13:e18116.

- Goto T, Goto Y, Hagiwara Y, et al. Advancing emergency airway management practice and research. Acute Med Surg 2019;6:336-351.

- Cicardi M, Levy RJ, McNeil DL, et al. Ecallantide for the treatment of acute attacks in hereditary angioedema. N Engl J Med 2010;363:523-531.

- MacGinnitie AJ, Campion M, Stolz LE, Pullman WE. Ecallantide for treatment of acute hereditary angioedema attacks: Analysis of efficacy by patient characteristics. Allergy Asthma Proc 2012;33:178-185.

- Cicardi M, Banerji A, Bracho F, et al. Icatibant, a new bradykinin-receptor antagonist, in hereditary angioedema. N Engl J Med 2010;363:532-541.

- Lumry WR, Li HH, Levy RJ, et al. Randomized placebo-controlled trial of the bradykinin B2 receptor antagonist icatibant for the treatment of acute attacks of hereditary angioedema: The FAST-3 trial. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2011;107:529-537.

- Wentzel N, Panieri A, Ayazi M, et al. Fresh frozen plasma for on-demand hereditary angioedema treatment in South Africa and Iran. World Allergy Organ J 2019;12:100049.

- Wang K, Geiger H, McMahon A. Tranexamic acid for ACE inhibitor induced angioedema. Am J Emerg Med 2021;43:292.e5-292.e7.

- Beauchêne C, Martins-Héricher J, Denis D, et al. [Tranexamic acid as first-line emergency treatment for episodes of bradykinin-mediated angioedema induced by ACE inhibitors]. [Article in French]. Rev Med Interne 2018;39.10:772-776.

This article examines the differences between various mechanisms of angioedema, reviews clinical presentations and diagnostic considerations, and discusses management techniques.

Subscribe Now for Access

You have reached your article limit for the month. We hope you found our articles both enjoyable and insightful. For information on new subscriptions, product trials, alternative billing arrangements or group and site discounts please call 800-688-2421. We look forward to having you as a long-term member of the Relias Media community.