Endometriosis and the Gut Microbiome: Nutritional Prospects in the Treatment of a Chronic Disease

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Endometriosis is a debilitating gynecological condition that affects about 10% of reproductive-age women, resulting in healthcare costs of $22 billion annually.

- It typically presents with heavy menstrual bleeding, dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, chronic pelvic pain, dyschezia, and infertility.

- Endometriosis is characterized by the presence of endometrial glands and stroma in any extrauterine site, such as the ovary, fallopian tubes, pelvic peritoneum, rectovaginal space, bowel, and, rarely, lungs and brain.

- On average, women seek consultation from three different healthcare providers over several years to receive a diagnosis of endometriosis. The delay in care results in significant long term morbidity. The constellation of nonspecific symptoms characterizing endometriosis creates a diagnostic challenge for clinicians.

- Not only do women experiencing endometriosis have typical symptoms of gynecologic disease, including heavy or irregular menses and pelvic pain, but they may experience constipation, bloating, rectal pain, irritable bowel syndrome, anxiety, depression, fatigue, and low back pain. This endometriosis phenome can contribute to a delay in care, since many women have unremarkable findings on physical examination and diagnostic imaging.

- Many women seek medical care from not only their primary care providers but also from gastroenterologists and gynecologists to seek solutions to their symptoms. Studies reveal that many gastrointestinal symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome and endometriosis tend to overlap, resulting in confusion of diagnosis and delay in care.

- Available medical therapies do not provide a definitive cure, so management is focused on reducing pain and minimizing surgical intervention.

- Recently, the importance of the influence of the gut microbiota has been identified along with the potential effect of treatment with probiotics.

Introduction

Endometriosis is a debilitating gynecological condition that affects about 10% of reproductive-age women.1,2 It can present with heavy menstrual bleeding, dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, chronic pelvic pain, dyschezia, and infertility.3

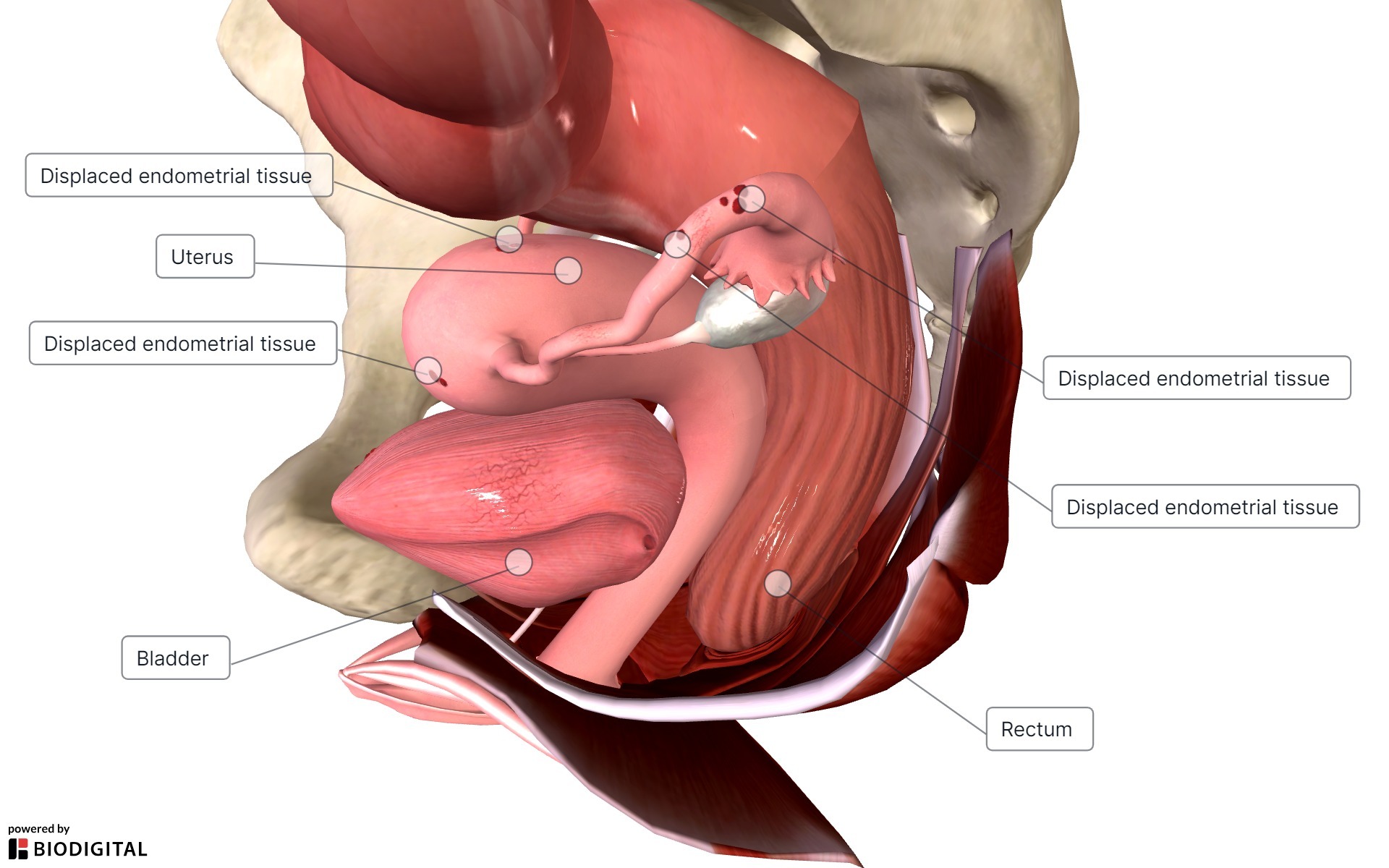

Endometriosis is characterized by the presence of endometrial glands and stroma in any extrauterine site, such as the ovary, fallopian tubes, pelvic peritoneum, rectovaginal space, bowel, and, rarely, lungs and brain.1 (See Figure 1.) These endometrial implants are sensitive to hormonal fluctuations of the menstrual cycle much like the uterine endometrial tissue from which it is derived.1 As such, these extrauterine endometrial implants also bleed and lead to fibrotic scarring and cyclic or persistent pelvic pain.1

Figure 1. Endometriosis |

|

Standard treatment of endometriosis may involve the use of pain relievers such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), hormonal therapy and modulators, and/or surgical removal of endometriotic tissue, depending on the patient’s individual circumstances.3 Endometriosis can affect women from prepuberty to menopause, with the majority experiencing symptoms in their mid- to late reproductive ages (30-40s).1 A family history of endometriosis seems to increase the risk.3 Endometriosis also is strongly associated with cardiovascular risk factors and thin habitus.4,5 The gold standard diagnosis involves surgical pathologic sampling of endometrial implants.1,4,5 Yet, this method can be costly and exposes the patient to disproportionate surgical risks to treat this chronic medical problem.6

On average, women seek consultation from three different healthcare providers over several years to receive a diagnosis of endometriosis. The delay in care results in significant long-term morbidity.3,6,7 The health burden of this disease is great, leading to healthcare costs of $22 billion annually in the United States.3 To date, there is no definitive cure for endometriosis.

Modern Treatment Modalities

Although available medical therapies do not provide a definitive cure, management is focused on reducing pelvic pain and minimizing surgical intervention.1 NSAIDs primarily are used to treat endometriosis-related dysmenorrhea, but studies do not reveal their superiority vs. placebo.1,2 Readily available, they can be used as treatment for primary dysmenorrhea or adjunctive endometriosis treatment with other hormonal therapies.

Combined hormonal contraceptives (CHCs) and progestins are considered first-line pharmacological therapy because of their ability to inhibit ovulation through the creation of a stable hormonal environment, which in turn will suppress the growth of ectopic endometrial implants and reduce inflammation and pain.4 They can be used long term and usually are well-tolerated, cost-effective, and safe.1,4

When CHCs and progestins cannot be used or do not achieve the desired effects, gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogs and antagonists, such as leuprolide depot, goserelin, and elagolix, may be given.4 Surgical therapy can be conservative or extirpative.4

Conservative endometriosis surgery aims to preserve the reproductive potential of patients and includes excision, ablation, and cauterization of endometriotic lesions. Extirpative surgery is reserved for extensive disease or disease refractory to other treatments and includes bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, hysterectomy, and excision and lysis of adhesions.

Unfortunately, symptoms may recur or persist despite optimal medical and surgical management.3 Studies reveal nearly half of women with endometriosis are dissatisfied with their disease treatment and would like for their caregivers to have a better understanding of the disease.7,8

Prevailing Theories of the Development of Endometriosis

Although the exact mechanism by which endometriosis develops is not clearly understood, two theories categorize potential origins: the in situ theory and the transplantation theory.9 Since 1870, various theories have been proposed as possible etiologies in endometriosis development.9,10 Theories such as retrograde menstruation, coelomic metaplasia, and venous and lymphatic spread attempt to hypothesize both pelvic and unusual extra pelvic sites of endometriosis.1,9 Several case reports and reviews have identified endometriosis in the lung and pleural space, kidney, and eyelid.11-13

The in situ theory encompasses hypotheses in which the ectopic extrauterine endometriosis cells arise from metaplastic local tissues or through embryologic origin.9 In 1870, Waldeyer submitted that endometriosis tissue originated from germinal epithelial tissue of the ovary.10 Another hypothesis describes endometriosis tissue having developed from the differentiation of aberrant embryonic cells rests along the migration of Mullerian duct pathway.9 This could justify why endometriosis tissue commonly is found in the cul-de-sac, uterosacral ligaments, and broad ligaments, yet it does not explain why endometriosis is found in locations outside of Mullerian duct derivatives.9

The transplantation theory attempts to reconcile inconsistencies seen in the in situ hypothesis. Sampson’s theory of retrograde menstruation suggests endometrial tissue flows backward into the peritoneal cavity via the fallopian tubes, supporting the idea of a transplantation mechanism.1,9,14,15 Furthermore, it is postulated that a dysregulated immune response (increased oxidative stress, proinflammatory cytokines, growth factors, activation of peritoneal macrophages, autoantibodies, and angiogenesis) may facilitate the growth of ectopic endometrial tissue, which can explain why some women develop endometriosis subsequent to retrograde menstruation and others do not.14 Yet, Sampson considered a venous spread theory of endometriosis, since retrograde menstruation could not explain distant dissemination of the disease.16 Another theory of lymphatic spread proposes endometrial cells escape into the lymphatic system and circulate to various body locations, leading to unusual implantation of the endometrial cells.9

Nonspecific Symptoms Leading to New Insight in Pathophysiology

The constellation of nonspecific symptoms characterizing endometriosis creates a diagnostic challenge for clinicians. Not only do women with endometriosis experience typical symptoms of gynecologic disease, including heavy or irregular menses and pelvic pain, others may experience constipation, bloating, rectal pain, irritable bowel syndrome, anxiety, depression, fatigue, and low back pain.1,4,17 This endometriosis phenome can contribute to a delay in care, since many women have unremarkable findings on physical examination and diagnostic imaging.3

Many women seek medical care from not only their primary care providers but also from gastroenterologists and gynecologists to seek solutions to their symptoms. Studies reveal that many gastrointestinal symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome and endometriosis tend to overlap, resulting in confusion of diagnosis and delay in care.18,19 Yet, this related symptomatology between gastrointestinal disorders and endometriosis can reveal potential connections of shared pathophysiology.

Elevations in mast cells and cytokine release in both irritable bowel syndrome and endometriosis may provide insight into disease etiology.19 Further, endometriosis and irritable bowel syndrome share neuropathic nociceptive referred pain signaling pathways as a result of deep peritoneal endometriotic implant nerve damage.19 Most interestingly, there appears to be an effect of the gut microbiome that leads to shared disease symptomatology.14,19,20

New Insight in the Pathophysiology of Endometriosis and the Gut Microbiome

In 2016, Laschke and Menger hypothesized a gut microbiome link to the pathogenesis of endometriosis.21 Recognizing the estrogen-dependent cyclic proliferation of endometrial tissue, a connection between estrogen-metabolizing gut flora was surmised.21-23 Terms and definitions related to this link are found in Table 1.

Table 1. Terms and Definitions |

|

Term |

Definition |

Gut microbiota |

A population of microorganisms (protists, viruses, bacteria, fungi) living within and on the body, leading to a symbiotic relationship |

Gut dysbiosis |

An imbalance of gut microbiota leading to impairment of metabolic processes as the result of a gain of pathologic microbes |

Gut microbiome |

A collection of microbial genetic material that leads to maintenance of host homeostasis involving the immune, metabolic, and nervous systems |

Estrobolome |

The collection of genes, including the microbiome, that leads to the production of estrogen |

Probiotic |

Microorganisms that provide healthful benefit to the host |

The authors suggested chronic low-grade inflammation received from the peritoneal cavity caused by gut dysbiosis could lead to potential implantation and neovascularization of endometrial implants to the peritoneal cavity.21 It is hypothesized as the reason why some women develop endometriosis and other do not. Since then, continued emerging evidence has revealed a link between endometriosis and the gut microbiota, suggesting endometriosis as the result of gut microbiome destabilization.14,20-23

Gut Microbiota and its Relationship to Health

The gut microbiota is a population of microorganisms through symbiosis that leads to a maintenance of host homeostasis involving the immune, metabolic, and nervous systems.22,24,25 A dysbiosis, or imbalance, of this homeostasis can lead to several pathologic disorders, such as obesity, atherosclerosis, type 2 diabetes, metabolic syndrome, and rheumatologic disease.24,26,27

It is suggested that imbalance of pathologic microorganisms leads to activation of immune response, contributing to the induction of a diseased state and entry of enterotoxins that lead to permeability of the intestine.24 This “leaky gut” can allow for the passage of endotoxins, inflammatory cytokines, and pathogenic organisms into the peritoneal cavity and lead to systemic chronic low-grade inflammation.20,28,29

Pathophysiologic mechanisms by which gut dysbiosis can lead to chronic disease include allowing for opportunistic pathogens to overgrow, loss of protective gut microorganisms, and a combination of the two, which may be requisite for the onset of disease.30

Endometriosis and the Gut Microbiota Connection

Endometriosis can be best characterized by two pathologic coexisting processes manifesting into one disease. The characteristic immune-activated endometrial cells are distributed in a retrograde fashion through the fallopian tubes and settle in extra-uterine sites within the peritoneal cavity.1,3,22 Gut dysbiosis leads to a weak intestinal barrier, immune dysregulation, dysfunctional estrobolome, and altered progenitor stem cells.22,31,32

Endometrial cells distributed in a retrograde fashion in Sampson’s theory are the key step to allow for menstrual tissue to implant ectopically.1,3 These endometrial cells also are noted to be dysbiotic, as seen in the bacterial contamination hypothesis.31,33,34 This hypothesis suggests dysregulated female genital tract microbiota are transplanted into the peritoneal cavity via retrograde menstruation, thus inoculating the abdomen and pelvis.33 Studies indicate a decreased presence of Lactobacillus species and an increased presence of bacterial vaginosis-causing species, such as Escherichia coli, in menstrual effluent among people with endometriosis.31,33-35

Further, a systematic review indicated a higher presence of a gram-negative phylum, Proteobacteria, in women affected by endometriosis.14 Gardnerella was found to be significantly increased in the cervical, endometrial, and vaginal mucus of endometriosis cohorts, yet decreased in stool samples.14

As such, the presence of bacteria in the abdominal cavity pre-stimulates macrophages and neutrophils and readies them for recruitment in the peritoneum.31 Their presence activates the production of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) by macrophages to create pathologic angiogenesis between endometriotic implants and the peritoneum.31 This process of angiogenesis involving VEGF also is upregulated by estradiol and progesterone.22,31 Furthermore, activated peritoneal macrophages secrete tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α and interleukin (IL) 8, potent inducers of angiogenesis and lesion proliferation.31 After the disease processes evolve symbiotically, regular menstruation of the ectopic endometrial implants continues the cycle of chronic immunologic clearing of menstrual tissue and can lead to diffuse scarring, with neuronal hypersensitivity and chronic neuropathic pain.36,37

The final piece in this proposed multifaceted pathophysiology involves dysregulation of the secretion of estrogen via the affected estrobolome.22 The estrobolome is a population of the gut microbiome with the ability to produce deconjugated estrogen via their use of β-glucuronidase secretion.22,38 Among women with endometriosis, concentrations of microbiome with this β-glucuronidase capacity are increased. As such, this excess production in active estrogen stimulates the estrogen receptor (ER)-α seen in higher concentrations among women with endometriosis, leading to further proliferation of ectopic endometrial tissue.22,38

Nutritional Supplementation and its Effect on Endometriosis and Gut Microbiota-Directed Therapy

The gut microbiota becomes destabilized with different dietary exposures, such as the consumption of excess carbohydrates and saturated fats, and may lead to leakage of inflammatory molecules through the intestinal barrier.24 The inflammatory molecules settle in the abdominal or pelvic cavity, and if endometrial tissue is present there, the cells may neovascularize and adhere to the space in the peritoneal cavity. Understanding the connection between the gut microbiome and endometriosis shows promise in treating this challenging condition. By potentially identifying inflammatory triggers, women may be able to manage their endometriosis symptoms by improving their gut microbiome through dietary changes. Studies reveal omega-3 fatty acids and vitamins D, A, and E may play a role in improving the gut microbiome and thereby improve symptoms of endometriosis.23,39

Dietary Exposure and Nutritional Treatment Strategies

There currently are no curative therapies in the treatment of endometriosis. Standard medical and surgical treatment may fall short in the amelioration of symptoms. Connecting gut health with the development of endometriosis leads to therapies involving nutritional supplementation and the avoidance of certain foods. Several studies have revealed the associations of probiotics, omega-3 fatty acids, vitamins A and D, and the consumption of trans fats with endometriosis.23,31,39-43

Probiotics

A rationale for treatment based on the gut-dysbiosis pathophysiologic model of endometriosis includes the use of probiotics.35 Probiotic-enhancing diets and supplements are used to treat various medical conditions and hold promise for enriching health, with the aim to replenish vital symbiotic microorganisms important to its host’s health.44,45

In 2014, the International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) issued a consensus statement ascribing that certain probiotics alone may provide health benefits.46 Endometriotic microbiota reveal diminished presence of Lactobacillus species, with an overabundance of pathogenic polymicrobial species commonly seen in bacterial vaginosis.31 As such, probiotic intervention shows promise in treating endometriosis. The evidence supports improvement of endometriosis symptoms and inflammation with treatment with Lactobacillus.31 A pilot placebo-controlled randomized trial revealed a significant reduction in overall pain score after eight weeks of intervention with Lactobacillius.47

Vitamin D

The vitamin D system of interactions is associated with several gynecologic disorders, from ovarian cancer to polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS).42 This influence on reproductive health also is noted among women with endometriosis.39,41,48 Low levels of vitamin D are noted among women with endometriosis and may be a risk factor for development.48

Vitamin D is involved in various metabolic and hormonal regulatory processes in the body. Specifically, the mechanism for this includes immunoregulation, the reduction of inflammation, and the reduction of angiogenesis.42 Given the inflammatory milieu seen in endometriosis, the associations are logical.

Parazzini et al reports on the observation that vitamin D fuels T-regulatory cells and secretion of IL-10 and downregulates inflammatory cytokine release.40 A systematic review and meta-analysis revealed women with low vitamin D levels had endometriosis and showed a negative correlation in the severity of the disease.42

Other studies demonstrate nonsignificant associations between endometriosis risk and adequate vitamin D intake.40 Nodler et al revealed that, among young women and adolescents supplementing with vitamin D, there were significantly improved endometriosis symptoms, similar to placebo, compared to no treatment.41 In rat models, treatment of endometriosis with vitamin D decreased IL-6 levels in peritoneal fluid correlated with the endometriosis inflammatory response.39

Vitamin A

Associations with decreased vitamin A and related retinoids also are noted in the pathophysiology of endometriosis.23 Vitamin A increases the production of gut microbiome-produced butyrate, an important regulator in gut barrier maintenance, immune regulation, and mitochondrial function.23 Endometrial tissue cyst proliferation was noted to be suppressed in biologic models after treatment with all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA).49 ATRA seems to affect the factors altered in endometrial cells considered to be impaired in endometriosis lesions.23 Further, in cell models, retinoic acid was seen to reduce levels of IL-6, a cytokine associated with endometriosis lesions.49,50

Omega-3

Oral omega-3 supplementation has been shown to reduce endometriosis-related pain and lesion size, and allow for fertility-promoting alternative treatments.51 The role of omega-3 in pain management has been well documented.52-54 Specifically, omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid is a key regulator of prostaglandin and cytokine release, and it competes with pro-inflammatory omega-6 to produce anti-inflammatory lipid mediators.40,55 Sources of omega-3 can be found in nuts, fish, krill, algae, and leafy greens.

Studies revealed increased dietary exposure to omega-3 decreased the risk of endometriosis.51 Further, a pilot study revealed endometriosis pain scores were found to be reduced among women who supplement with omega-3. A randomized, controlled, clinical trial is underway.51 Other studies suggested modest results, with nonsignificant reductions in pain scores among adolescent girls and young women who supplemented with omega-3.41

Parazzini et al reported that women who had the highest rates of consumption of omega-3 were 22% less likely to be diagnosed with endometriosis.40 In laboratory studies, reduction in endometriosis implants were noted in the rat model, and adhesive endometriotic disease and lesions were reduced in mice compared to controls.39,43

Trans Fat Intake

Trans fat is the term used to describe triglycerides that are rich in trans fatty acids. Produced synthetically, they can be used in food for shelf stabilization, texture, and flavor. In many methods of food technology, they are partially hydrogenated from vegetable oils rich in polyunsaturated fatty acids. Trans fats can be found in many foods, such as margarine, French fries, donuts, cookies, and crackers.

Higher trans fat consumption is associated with higher signs of systemic inflammation.56 The Nurses’ Health Study revealed that women in the highest quartile of trans fat consumption were at a 48% increased risk of endometriosis.40 Further, another study revealed that women with higher consumption of trans fat increased the risk of laparoscopically present endometriosis.57 This study suggested that increasing omega-3 consumption and reducing trans fat consumption is a modifiable risk factor in the treatment of endometriosis.57

Clinical Vignette

Amy is a 32-year-old administrative assistant presenting as a new patient with daily abdominal bloating and associated pelvic discomfort, and painful menstrual periods.

History of Present illness

The patient experiences cyclic pelvic pain that usually occurs during menstruation. The pain is described as sharp and cramping, and radiates to the lower back (sacrum) and thighs.

She experiences diarrhea, painful defecation (dyschezia), and painful urination (dysuria) during the first day of her menstrual cycle. Additionally, she also experiences pain during sexual intercourse (dyspareunia).

Medical History

• Adult acne

• Generalized anxiety disorder

Obstetric History

The patient has no previous pregnancies.

Gynecologic History

The patient reports experiencing painful menstrual periods (dysmenorrhea) since her early teenage years, and remembers the severe pain of her first period. The pain has progressively worsened over time and often is accompanied by heavy menstrual bleeding.

Her periods are every 28 days, lasting seven days, and she uses one to two pads per hour on the second day of her period.

She has regular, normal cervical cancer screenings and is sexually active with a male partner. She is using condoms for birth control to avoid “hormones.”

She has never had a sexually transmitted infection.

Family History

There is a family history of endometriosis, with her mother and maternal aunt being diagnosed with the condition.

Her mother had a myocardial infarction at age 52 years, despite being a marathon runner.

Medical Treatments

She uses a combination over-the-counter medication of acetaminophen, caffeine, and pyrilamine maleate that only mildly alleviates her symptoms.

Surgical History

The patient has not undergone any surgical procedures.

Medications

• Acetaminophen

• Caffeine

• Pyrilamine maleate combination tablet

Social History

The patient is a nonsmoker and does not consume alcohol excessively.

She leads a physically active lifestyle but is starting to experience pelvic and perirectal pain during jogging that causes her to stop prematurely.

She follows a balanced diet.

Review of Systems

The patient denies any significant complaints in other body systems, except for the symptoms related to endometriosis.

Vital Signs

• Blood pressure: 110/75 mmHg

• Height: 5’4”

• Weight: 121 lbs

• Body mass index: 20.9

Physical Examination

On examination, she has recent acne scars over her chin with scattered comedones.

Tenderness is noted upon palpation of the lower abdomen and pelvis with mild tympanic distension. No other significant abnormalities are observed during the physical examination.

Her bimanual gynecologic exam reveals tender sub-centimeter nodularity at the posterior cul-de-sac.

Differential Diagnoses

• Dysmenorrhea

• Endometriosis

• Polycystic ovary syndrome

• Interstitial cystitis

• Irritable bowel syndrome

• Pelvic inflammatory disease

Diagnostic Evaluation

• Pelvic ultrasound: Normal

• Triglycerides: 160 mg/dL

• High-density lipoprotein: 39 mg/dL

• Glucose (fasting): 99 mg/dL

• Hemoglobin A1c: 5.7%

• Insulin level (fasting): 18 mIU/mL

• Complete blood count: Normal

• Sexually transmitted infections screen: Negative

• Vitamin D level: 19 ng/mL

• Urinalysis: Negative

Second Visit: Two Weeks Later

The primary care physician diagnoses her with insulin resistance and suspected endometriosis. He recommends NSAIDs for pain relief and reduction in simple sugars.

Third Visit: Three Months Later

The patient reports that after using ibuprofen 400 mg orally every four hours on the first day of her menstrual cycle, her pain is somewhat improved.

She has performed internet research and has read about gluten-free diets. She reports that after avoiding gluten, her bloating has improved, but she continues to have painful menses that is keeping her from going to work.

She is starting to have significant anxiety before her menses starts. She is referred to gynecology for consultation.

Conclusion

The available evidence suggests and supports a new approach in the understanding and treatment of endometriosis. Current trends reveal patients are searching for lifestyle and nutritional modalities to remedy the root cause of the disease. Although traditional medical and surgical approaches provide proven improvements of endometriosis-related symptom sequelae, they largely focus on secondary prevention of the disease. Many affected women are dissatisfied with symptom-focused treatments. Clinicians may experience a sense of a diminished capacity to care for endometriosis patients.

The primary care physician may diagnose endometriosis clinically by narrowing on the multi-organ system symptoms that center on the menstrual cycle. Pelvic ultrasonography will determine the presence of endometriomas that would need surgical attention by the consulting gynecologist. A gynecologic consultation also could determine the need for surgical exploration with laparoscopy in patients without advanced endometriotic disease or recalcitrant to medical therapy. Yet, outside of the need for surgery, the primary care physician could comfortably treat endometriosis with the medical and nutritional treatments reviewed earlier. More and more chronic diseases are found to be associated with gut dysbiosis.

As such, the reviewed relationship between the gut microbiome and the development of endometriosis provides a clear and logical pathway of pathophysiology and disease treatment. The gut dysbiosis model of endometriosis may improve both physician and patient satisfaction with treatment planning and overall primary prevention of disease.

References

- Advincula A, Truong M, Lobo RA. Endometriosis: Etiology, pathology, diagnosis, management. In: Gershenson DM, Lentz GM, Valea FA, Lobo RA, eds. Comprehensive Gynecology. 8th ed. Elsevier;2022:409-427e5.

- McLeod BS, Retzloff MG. Epidemiology of endometriosis: An assessment of risk factors. Clin Obstet Gynecol 2010;53:389-396.

- Horne AW, Missmer SA. Pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management of endometriosis. BMJ 2022;379:e070750.

- Falcone T, Flyckt R. Clinical management of endometriosis. Obstet Gynecol 2018;131:557-571.

- Agarwal SK, Chapron C, Giudice LC, et al. Clinical diagnosis of endometriosis: A call to action. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2019;220:354.e1-354.e12.

- Kiesel L, Sourouni M. Diagnosis of endometriosis in the 21st century. Climacteric 2019;22:296-302.

- Wróbel M, Wielgoś M, Laudański P. Diagnostic delay of endometriosis in adults and adolescence-current stage of knowledge. Adv Med Sci 2022;67:148-153.

- Gouesbet S, Kvaskoff M, Riveros C, et al. Patients’ perspectives on how to improve endometriosis care: A large qualitative study within the ComPaRe-Endometriosis e-cohort. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2023;32:463-470.

- Laganà AS, Garzon S, Götte M, et al. The pathogenesis of endometriosis: Molecular and cell biology insights. Int J Mol Sci 2019;20:5615.

- Waldeyer. Die epithelialen Eierstocksgeschwülste, insbesondere die Kystome. Arch Für Gynäekologie 1870;1:252-316.

- Sharghi KG, Ramey NA, Rush PS, Grider DJ. Endometriosis of the eyelid, an extraordinary extra-abdominal location highlighting the spectrum of disease. Am J Dermatopathol 2019;41:593-595.

- Nawaz MM, Masood Y, Usmani AS, et al. Renal endometriosis: A benign disease with malignant presentation. Urol Case Rep 2022;43:102110.

- Andres MP, Arcoverde FVL, Souza CCC, et al. Extrapelvic endometriosis: A systematic review. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 2020;27:373-389.

- Leonardi M, Hicks C, El-Assaad F, et al. Endometriosis and the microbiome: A systematic review. BJOG 2020;127:239-249.

- Sampson JA. Peritoneal endometriosis due to the menstrual dissemination of endometrial tissue into the peritoneal cavity. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1927;14:422-469.

- Sampson JA. Metastatic or embolic endometriosis, due to the menstrual dissemination of endometrial tissue into the venous circulation. Am J Pathol 1927;3:93-110.43.

- Taylor HS, Kotlyar AM, Flores VA. Endometriosis is a chronic systemic disease: Clinical challenges and novel innovations. Lancet 2021;397:839-852.

- Peters M, Mikeltadze I, Karro H, et al. Endometriosis and irritable bowel syndrome: Similarities and differences in the spectrum of comorbidities. Hum Reprod 2022;37:2186-2196.

- Yu V, McHenry N, Proctor S, et al. Gastroenterologist primer: Endometriosis for gastroenterologists. Dig Dis Sci 2023;68:2482-2492.

- Talwar C, Singh V, Kommagani R. The gut microbiota: A double-edged sword in endometriosis. Biol Reprod 2022;107:881-901.

- Laschke MW, Menger MD. The gut microbiota: A puppet master in the pathogenesis of endometriosis? Am J Obstet Gynecol 2016;215:68.e1-4.

- Salliss ME, Farland LV, Mahnert ND, Herbst-Kralovetz MM. The role of gut and genital microbiota and the estrobolome in endometriosis, infertility and chronic pelvic pain. Hum Reprod Update 2021;28:92-131.

- Anderson G. Endometriosis pathoetiology and pathophysiology: Roles of vitamin A, estrogen, immunity, adipocytes, gut microbiome and melatonergic pathway on mitochondria regulation. Biomol Concepts 2019;10:133-149.

- Lobionda S, Sittipo P, Young Kwon H, Kyung Lee Y. The role of gut microbiota in intestinal inflammation with respect to diet and extrinsic stressors. Microorganisms 2019;7:271.

- Sittipo P, Lobionda S, Kyung Lee Y, Maynard CL. Intestinal microbiota and the immune system in metabolic diseases. J Microbiol 2018;56:154-162.

- Shreiner AB, Kao JY, Young VB. The gut microbiome in health and in disease. Curr Opin Gastroenterol 2015;31:69-75.

- Konig MF. The microbiome in autoimmune rheumatic disease. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2020;34:101473.

- Balzan S, de Almeida Quadros C, de Cleva R, et al. Bacterial translocation: Overview of mechanisms and clinical impact. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2007;22:464-471.

- Camilleri M. Leaky gut: Mechanisms, measurement and clinical implications in humans. Gut 2019;68:1516-1526.

- Wilkins LJ, Monga M, Miller AW. Defining dysbiosis for a cluster of chronic diseases. Sci Rep 2019;9:12918.

- Jiang I, Yong PJ, Allaire C, Bedaiwy MA. Intricate connections between the microbiota and endometriosis. Int J Mol Sci 2021;22:5644.

- Zizolfi B, Foreste V, Gallo A, et al. Endometriosis and dysbiosis: State of art. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2023;14:1140774.

- Khan KN, Fujishita A, Hiraki K, et al. Bacterial contamination hypothesis: A new concept in endometriosis. Reprod Med Biol 2018;17:125-133.

- Khan KN, Kitajima M, Hiraki K, et al. Escherichia coli contamination of menstrual blood and effect of bacterial endotoxin on endometriosis. Fertil Steril 2010;94:2860-3.e1-3.

- Ser HL, Au Yong SJ, Shafiee MN, et al. Current updates on the role of microbiome in endometriosis: A narrative review. Microorganisms 2023;11:360.

- McKinnon BD, Bertschi D, Bersinger NA, Mueller MD. Inflammation and nerve fiber interaction in endometriotic pain. Trends Endocrinol Metab 2015;26:1-10.

- Yan D, Liu X, Guo SW. Nerve fibers and endometriotic lesions: Partners in crime in inflicting pains in women with endometriosis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2017;209:14-24.

- Baker JM, Al-Nakkash L, Herbst-Kralovetz MM. Estrogen-gut microbiome axis: Physiological and clinical implications. Maturitas 2017;103:45-53.

- Akyol A, ŞimŞek M, Ílhan R, et al. Efficacies of vitamin D and omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids on experimental endometriosis. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol 2016;55:835-839.

- Parazzini F, Viganò P, Candiani M, Fedele L. Diet and endometriosis risk: A literature review. Reprod Biomed Online 2013;26:323-336.

- Nodler JL, DiVasta AD, Vitonis AF, et al. Supplementation with vitamin D or [omega]-3 fatty acids in adolescent girls and young women with endometriosis (SAGE): A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr 2020;112:229-236.

- Qiu Y, Yuan S, Wang H. Vitamin D status in endometriosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2020;302:141-152.

- Herington JL, Glore DR, Lucas JA, et al. Dietary fish oil supplementation inhibits formation of endometriosis-associated adhesions in a chimeric mouse model. Fertil Steril 2013;99:543-550.

- Lynch SV, Pedersen O. The human intestinal microbiome in health and disease. N Engl J Med 2016;375:2369-2379.

- Plaza-Diaz J, Ruiz-Ojeda FJ, Gil-Campos M, Gil A. Mechanisms of action of probiotics. Adv Nutr 2019;10(suppl_1):S49-S66.

- Hill C, Guarner F, Reid G, et al. Expert consensus document. The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics consensus statement on the scope and appropriate use of the term probiotic. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014;11:506-514.

- Khodaverdi S, Mohammadbeigi R, Khaledi M, et al. Beneficial effects of oral Lactobacillus on pain severity in women suffering from endometriosis: A pilot placebo-controlled randomized clinical trial. Int J Fertil Steril 2019;13:178-183.

- Mehdizadehkashi A, Rokhgireh S, Tahermanesh K, et al. The effect of vitamin D supplementation on clinical symptoms and metabolic profiles in patients with endometriosis. Gynecol Endocrinol 2021;37:640-645.

- Yamagata Y, Takaki E, Shinagawa M, et al. Retinoic acid has the potential to suppress endometriosis development. J Ovarian Res 2015;8:49.

- Sawatsri S, Desai N, Rock JA, Sidell N. Retinoic acid suppresses interleukin-6 production in human endometrial cells. Fertil Steril 2000;73:1012-1019.

- Abokhrais IM, Denison FC, Whitaker LHR, et al. A two-arm parallel double-blind randomised controlled pilot trial of the efficacy of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids for the treatment of women with endometriosis-associated pain (PurFECT1). PLoS One 2020;15:e0227695.

- Harel Z, Biro FM, Kottenhahn RK, Rosenthal SL. Supplementation with omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids in the management of dysmenorrhea in adolescents. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1996;174:1335-1338.

- Cordingley DM, Cornish SM. Omega-3 fatty acids for the management of osteoarthritis: A narrative review. Nutrients 2022;14:3362.

- Sesti F, Capozzolo T, Pietropolli A, et al. Dietary therapy: A new strategy for management of chronic pelvic pain. Nutr Res Rev 2011;24:31-38.

- Gazvani MR, Smith L, Haggarty P, et al. High omega-3:omega-6 fatty acid ratios in culture medium reduce endometrial-cell survival in combined endometrial gland and stromal cell cultures from women with and without endometriosis. Fertil Steril 2001;76:717-722.

- Oteng AB, Kersten S. Mechanisms of action of trans fatty acids. Adv Nutr 2020;11:697-708.

- Missmer SA, Chavarro JE, Malspeis S, et al. A prospective study of dietary fat consumption and endometriosis risk. Hum Reprod 2010;25:1528-1535.

Endometriosis is characterized by the presence of endometrial glands and stroma in any extrauterine site, such as the ovary, fallopian tubes, pelvic peritoneum, rectovaginal space, bowel, and, rarely, lungs and brain. Standard treatment of endometriosis may involve the use of pain relievers such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, hormonal therapy and modulators, and/or surgical removal of endometriotic tissue. On average, women seek consultation from three different healthcare providers over several years to receive a diagnosis of endometriosis. The delay in care results in significant long-term morbidity.

Subscribe Now for Access

You have reached your article limit for the month. We hope you found our articles both enjoyable and insightful. For information on new subscriptions, product trials, alternative billing arrangements or group and site discounts please call 800-688-2421. We look forward to having you as a long-term member of the Relias Media community.