Emergency Department Evaluation of Vertigo and Dizziness

May 1, 2023

Related Articles

-

Echocardiographic Estimation of Left Atrial Pressure in Atrial Fibrillation Patients

-

Philadelphia Jury Awards $6.8M After Hospital Fails to Find Stomach Perforation

-

Pennsylvania Court Affirms $8 Million Verdict for Failure To Repair Uterine Artery

-

Older Physicians May Need Attention to Ensure Patient Safety

-

Documentation Huddles Improve Quality and Safety

AUTHORS

Michael Anthony DiPietro, MD, Assistant Professor, Emergency Medicine, Penn State Health Milton S. Hershey Medical Center

Randall Lee Ung, MD, PhD, Emergency Medicine Resident, Penn State Health Milton S. Hershey Medical Center

PEER REVIEWER

Frank LoVecchio, DO, MPH, FACEP, Vice-Chair for Research, Medical Director, Samaritan Regional Poison Control Center, Emergency Medicine Department, Maricopa Medical Center, Phoenix, AZ

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

- Vertigo is a frustrating complaint for many patients and emergency physicians.

- Vertigo is defined as the sensation of self-motion when no motion is occurring and is the characteristic symptom of vestibular dysfunction.8

- The differential for vertigo is broad, ranging from benign peripheral lesions, such as benign paroxysmal positional

vertigo, to devastating strokes. Management of vertigo is difficult for providers, consequently. - Further complicating matters is that patients often have difficulty describing their symptoms with vague and inconsistent descriptions.9

Epidemiology

Many patients present with a chief complaint of dizziness or vertigo. The incidence of these chief complaints is increasing and reaches up to 4% of all emergency department (ED) visits.1,2 Vertigo affects both men and women, but it is about two to three times more common in women than men.3 Dizziness, including vertigo, affects about 15% to 20% of adults yearly, and the prevalence increases with age.3

However, vertigo does not encompass a single diagnosis, but rather it is a manifestation of many potential causes. One study described more than 46 different diagnoses among only 106 patients seeking treatment for dizziness.2 In general, causes can be divided into peripheral (inner ear, vestibular nerve) and central (brainstem, cerebellum) pathology. Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) is the most common cause of vertigo in all clinical settings, including the ED, and this also is the most common form of peripheral vestibular dysfunction.4-6 BPPV has a lifetime prevalence of 2.4% and accounts for around 24% of all hospital visits due to dizziness/vertigo.5 The next most common causes of peripheral vertigo include vestibular neuritis, vestibular migraine, labyrinthitis, and Ménière’s disease.

The most common cause of central vestibular dysfunction is an ischemic stroke of the posterior fossa, which contains the cerebellum and the brainstem.4 The incidence of cerebrovascular disease in patients presenting to the ED with a complaint of vertigo ranges from 3% to 5%.7 Notably, in cases of missed strokes among ED patients, vertigo is the most common associated symptom, and some studies have shown up to 10% of cerebellar strokes may present with initial symptoms that mimic vestibular neuritis.7

Etiology

In patients presenting with a chief complaint of dizziness, vertigo comprises a subset of complaints, and making this distinction is important to narrow the differential diagnoses. This article will focus on the potential etiologies of vertigo, since the etiologies of dizziness are too numerous to report. Vestibular, cardiovascular, musculoskeletal, metabolic, neurological, psychiatric, and infectious conditions all are commonly encountered diseases in patients presenting to the ED with complaints of dizziness.

Common Causes

BPPV: BPPV is the most common cause of vertigo in all clinical settings, including the ED. BPPV occurs because of the displacement of calcium-carbonate crystals, or otoconia, in the fluid-filled semicircular canals of the inner ear.4 As a result, when patients move their head in certain positions, they experience vertigo and nystagmus for less than two minutes, often around 20 seconds. BPPV is most common in elderly women, with a peak incidence in their 60s with a female-to-male ratio of 2.4:1. A meta-analysis found that risk factors for the recurrence of BPPV include female gender, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, osteoporosis, and vitamin D deficiency.10 Related to this is the finding that elderly women with a lack of physical activity have a 2.6 times higher risk of BPPV than those who participate in regular physical activity.10 Approximately 50% to 70% of BPPV cases occur with no known cause and are referred to as idiopathic or primary BPPV. The remaining cases are known collectively as secondary BPPV and are due to an underlying pathology, such as head trauma.5

Vestibular Neuritis: The second most common peripheral cause of vertigo is vestibular neuritis. The exact etiology of vestibular neuritis remains unclear; however, viral infection and resultant inflammation of the vestibular portion of the eighth cranial nerve appears to be the most likely cause, since a preceding or concurrent viral infection in the upper respiratory tract occurs in 43% to 46% of vestibular neuritis cases.8,11 It is estimated that vestibular neuritis is diagnosed in around 6% of patients who present to the ED with complaints of dizziness; however, this likely is an underrepresentation of the true incidence.11 Notably, vestibular neuritis often is misdiagnosed as labyrinthitis, given their similarities. Acute labyrinthitis is differentiated from vestibular neuritis by involvement of the cochlea causing auditory symptoms.8

Acute Ischemic Stroke: The most common cause of central vestibular dysfunction is an ischemic stroke of the brainstem and cerebellum.12 The risk factors for ischemic stroke of the posterior fossa are the same as those for a cortical ischemic stroke, including hypertension, diabetes, cigarette smoking, obesity, atrial fibrillation, sedentary lifestyle, hyperlipidemia, and hyper-coagulable state.13,14 Acute ischemic stroke accounts for up to 25% of patients who present with central vestibular dysfunction and 3% to 4% of all presentations of dizziness/vertigo to the ED in the United States.4 Isolated positional vestibular syndrome due to vascular vertigo/dizziness is rare. Vertigo/dizziness in cerebrovascular disorders usually is accompanied by other neurological signs and symptoms. However, even if it is rare that patients presenting with isolated vertigo have a cerebrovascular etiology, the future risk of stroke is higher in patients who present to the ED with a chief complaint of vertigo/dizziness than in those who present with non-dizziness visits, especially when several vascular risk factors exist.15

Less Common Etiologies

Vestibular Migraine: Vestibular migraine is a distinct variant of migraine that causes vestibular symptoms, with or without an accompanying migrainous headache.16,17 The overall prevalence of vestibular migraine is estimated to be 2.7%; however, it also likely is underdiagnosed. As in other types of migraine headaches, more women than men are affected. Thirty percent of patients have no headache before, during, or after the episode of vertigo.8 The diagnosis of vestibular migraine is made clinically.18 The criteria for diagnosis include patients with at least five episodes with vestibular symptoms that are moderate or severe in intensity and last five minutes to 72 hours; a current or previous history of migraine; one or more migraine features with at least 50% of the vestibular episodes, such as headache with pulsating quality, one-sided location, moderate or severe intensity, or aggravation by physical activity, as well as sensitivity to light or sound and visual aura; and not better accounted for by another vestibular or headache disorder.18

Ménière’s Disease: Ménière’s disease (or syndrome) is a disorder associated with an increased endolymph in the cochlea and labyrinth. It tends to occur in older men and women with equal prevalence between sexes. The exact etiology of Ménière’s disease is unknown, but genetic and environmental factors play a role.8,19 Attacks typically occur with abrupt onset, last between 20 minutes and 24 hours, and are associated with nausea, vomiting, and diaphoresis. The frequency of attacks varies and may be as frequent as several times per week. Auditory symptoms also will be present, including sensorineural hearing loss, tinnitus, and fullness in one ear. In between attacks, the patient usually is well; however, diminished hearing may persist.

Perilymph Fistula: A perilymphatic fistula is an abnormal communication between the perilymph-filled inner ear and outside the inner ear that can allow perilymph to leak from the cochlea or vestibule, most commonly through the round or oval window.20 Trauma, infection, or a sudden change in pressure inside the ventricular system may cause the tear. The diagnosis is suggested by the sudden onset of vertigo and hearing loss associated with head trauma, flying, scuba diving, severe straining, heavy lifting, coughing, or sneezing. Hearing loss also may be present.

Ototoxic Drugs: Ototoxicity is an undesirable effect of some drugs that induces reversible and irreversible damage of the inner ear structures, causing temporary or permanent tinnitus, hearing loss, and/or imbalance.8 Ototoxic effects depend on duration of therapy, route of administration, infusion rate, dosage, genetic predisposition, and altered renal and hepatic functions. Although a single administration may have ototoxic effects, long-term therapies have a higher risk of producing ototoxic side effects. The number of medications causing ototoxicity or vertigo/dizziness is vast.21 Some of the more common medications are listed in Table 1 (available online: https://bit.ly/3KFfS7y).21 Notable medications include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) that are a ubiquitous medication and can cause vertigo, especially if taken at increased doses. Fortunately, these changes often are reversible.21 Antibiotics, particularly aminoglycosides, also are known for their ototoxicity. Streptomycin, gentamicin, tobramycin, and sisomicin are particularly notable for their effects on the vestibular (as opposed to auditory) system.21 Toxicity from aminoglycosides, on the other hand, typically is irreversible.

Post-Traumatic Vertigo: Acute post-traumatic vertigo and unsteady gait are caused by a direct injury to the labyrinthine membranes and usually resolves in days to weeks.8 The onset of vertigo is immediate and commonly associated with nausea and vomiting. If vertigo occurs after head trauma, neuroimaging must be ordered to rule out acute intracerebral hemorrhage and/or concomitant fracture of the temporal bone. Head injuries also may lead to the displacement of otoconia in the semicircular canals and precipitate attacks of BPPV.6 Management is aimed at symptom management, and post-concussive symptoms should be referred to the appropriate clinic.6,8

Wallenberg Syndrome: Wallenberg syndrome is the infarction of the lateral medulla oblongata following occlusion of the vertebral artery or posterior inferior cerebellar artery (PICA) and also is referred to as lateral medullary or PICA syndrome.22 A lateral medullary infarction of the brainstem can present with vertigo as part of its initial clinical presentation. Other classic findings include ipsilateral facial numbness, loss of corneal reflex, Horner’s syndrome, and paralysis/paresis of the soft palate, pharynx, and larynx along with contralateral loss of pain and temperature sensation in the trunk and limbs.8 These patients require emergent neuroimaging and neurology referral.

Other peripheral etiologies include Ramsay-Hunt syndrome, otosclerosis of the inner ear, and cholesteatomas of the middle ear. Other central etiologies include cerebellar and brainstem tumors and demyelinating diseases, such as multiple sclerosis.

Pathophysiology

The central nervous system coordinates and integrates sensory information from the visual, vestibular, and proprioceptive systems. Vertigo arises from a mismatch of information from two or more of the involved senses caused by dysfunction in the sensory organ or its corresponding pathway.8

The vestibular system establishes the body’s orientation with respect to gravity. The semicircular canals of the inner ear are filled with endolymph, and at one end of each canal is an ampulla that contains the cupula. The cupula’s sensors track rotary motion. The three semicircular canals are arranged at right angles to one another and ensure that at least one canal is stimulated by every head rotation.3,4 The movement of fluid in the semicircular canals causes specialized hair cells inside the canals to move, causing afferent vestibular impulses to fire. Sensory input from the vestibular apparatus travels to the nucleus of the eighth cranial nerve. The medial longitudinal fasciculus, the red nuclei, the cerebellum, the parietal lobes, and the superior temporal gyrus of the cerebral cortex integrate the various sensory inputs.3,4,8 Connections between these structures and the oculomotor nuclei that drive the vestibulo-ocular reflex complete the system.

Balanced input from the vestibular apparatus on both sides is the norm, and asymmetry in the vestibular system accounts for vertigo. Asymmetry may result from damage or dysfunction in the peripheral system, such as the labyrinth or vestibular nerve, or a central disturbance in the cerebellum or brainstem.4,8 Rapid head movements accentuate the imbalance, while symmetric bilateral damage usually does not produce vertigo, but may lead to truncal or gait instability.

Clinical Features

History

The most common causes of peripheral vertigo often can be differentiated from central causes based on a thorough history and physical examination that will help determine the need for diagnostic testing. History taking should initially focus on differentiating vertigo from other causes of dizziness or presyncope.3 Vertigo often is described as a “room-spinning sensation”; however, this is not required for a diagnosis. In fact, patients’ descriptions may be inconsistent and nonspecific.9 Patients may describe a swaying or tilting sensation, or may state that they feel a sense of imbalance or disorientation. On the other hand, descriptions of triggers and timing often are more consistent and more valuable toward making the diagnosis.9 Each symptom revealed by the history should be detailed with respect to time course, severity, and exacerbation or alleviation, with the goal of separating peripheral vestibular from central nervous system pathology.3

Length of Symptomatic Episodes: One of the most important parts of the clinical history is the length of the symptomatic episodes, and often the exact diagnosis can be elucidated from this information. Episodes that are recurrent and last less than one minute are typical for BPPV. If these recurrent episodes last minutes to hours, it points more toward Ménière’s disease. Patients with Ménière’s disease also often have associated auditory symptoms, such as tinnitus and hearing loss. A single episode of vertigo that lasts for several minutes to hours has a broader differential and may be secondary to a vestibular migraine or a transient ischemic attack (TIA) that is related to the vascular areas of the labyrinth or brainstem. A single episode of vertigo that lasts for days can occur with vestibular neuritis, labyrinthitis, acute ischemic stroke of the brainstem or cerebellum, and multiple sclerosis.

Time Course of Symptoms: It also is important to determine the progression of symptoms over time. When the underlying symptoms are secondary to a vestibular etiology, the symptoms usually are not continuous and chronic. This is because the central nervous system (CNS) can compensate, and the feeling of vertigo usually subsides over days to weeks. If the patient recounts a history of constant vertigo or dizziness lasting months, the symptoms are most certainly central in nature.

Exacerbating and Relieving Factors: The next step is to obtain any factors that exacerbate or relieve the symptoms. If the symptoms worsen with motion of the head, this implies a vestibular etiology. As mentioned earlier, symptoms that began shortly after, or are worsened by, coughing, sneezing, exertion, or loud noises indicate a perilymphatic fistula. If the symptoms are worsened by bright lights and loud noises, it points toward a vestibular migraine.

Associated Symptoms: Finally, the symptoms associated with vertigo are helpful in narrowing down the etiology. Nausea and vomiting are typical of almost all etiologies of vertigo and do not help differentiate potential causes. To help differentiate between peripheral and central causes, it should be determined if there are any other neurologic deficits noted, such as truncal ataxia, difficulty walking, dysphagia, diplopia, dysarthria, numbness, or weakness. While the absence of these symptoms does not rule out a serious central process, the presence of these symptoms is concerning and should lead to further investigation of possible acute ischemic stroke or demyelinating disease. A history of hyperextension injury indicates potential vertebral artery dissection that also may present with persistent neck pain. Associated headache, visual aura, or photophobia points toward a vestibular migraine, while a history of recent viral illness or viral symptoms can help identify vestibular neuritis. If there is a presence of auditory symptoms, such as hearing loss or tinnitus, Ménière’s disease, labyrinthitis, and central lesions, particularly of the anterior inferior cerebellar artery, need to be considered.

Past Medical History: The patient’s past medical history also may provide a clue to the underlying etiology of vertigo. Patients with classic vasculopathy risk factors, such as hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes mellitus, and smoking history, have an increased likelihood of stroke. A prior history of migraine headaches increases the chance that vertigo is secondary to vestibular migraines. A history of head trauma in the past makes perilymphatic fistula or secondary BPPV a likely etiology. A patient’s medication list also should be reviewed. As discussed earlier, many medications may contribute to disequilibrium or vertigo.

Physical Examination

When combined with a complete history, a thorough physical exam can help further differentiate peripheral from central causes of vertigo. In every patient presenting with vertigo or dizziness, a full neurologic exam must be performed, including gait and balance. Patients with unilateral peripheral disorders often lean or fall toward the side of the lesion, while those patients with cerebellar lesions often are unable to walk without assistance. If it is determined from the history that the patient is experiencing vertigo, there are several unique physical exam maneuvers that should be performed. Collectively, these maneuvers are known as the HINTS exam. (See Table 2.) A HINTS exam consists of the head impulse test, nystagmus, test-of-skew, and hearing loss (often referred to as HINTS+ with the addition of hearing loss).

Table 2. HINTS Exam and Dix-Hallpike Test |

Head Impulse

Nystagmus

Test of Skew

Hearing Loss

Dix-Hallpike Test

|

Head Impulse Test: To perform a head impulse test, the examiner asks the patient to focus on a distant target. The examiner then turns the patient’s head quickly to the left and right around 15° to 20° from the midline. In normal subjects, the eyes remain fixated on the target, indicating an intact vestibulo-ocular reflex. An abnormal response is when the eyes are dragged off the target in the direction of the head turn, with a “catch up saccade” back to the target. This response implies a peripheral lesion resulting in a deficient vestibulo-ocular reflex in the direction of the head turn. Since most patients with stroke do not have a vestibular nerve deficit, a normal head impulse test is concerning for a central cause of vertigo in patients with persistent vertigo.

Nystagmus: Often, patients who present with vertigo demonstrate nystagmus on physical examination, and the pattern and severity of nystagmus can help differentiate peripheral from central disorders. A functional vestibular system allows one to maintain gaze during head rotation due to the vestibulo-ocular reflex. A unilateral dysfunction in the vestibular system causes the eyes to drift slowly away from a target and then correct with a fast movement in the opposite direction. The direction of this nystagmus is defined by the “fast” component of the nystagmus. In a peripheral vestibular lesion, the fast phase is away from the affected side. Also in peripheral lesions, the direction of the fast phase will be the same regardless of the direction of gaze, while central lesions may have nystagmus that changes directions. Peripheral lesions always have a horizontal component to the nystagmus and never present as purely rotational or vertical. Central causes of vertigo may present with spontaneous nystagmus, which can be seen when the patient is looking straight ahead, as well as rotational or vertical nystagmus.3

Test-of-Skew: Test-of-skew is accomplished by the cover-uncover test. While the patient looks at the examiner’s nose, the examiner covers one of the patient’s eyes and then covers the other eye. Any vertical or diagonally upward or downward movement of the eyes as they are uncovered indicates a central cause of vertigo.

Hearing Loss: A later addition to the HINTS exam is hearing loss, which increased both sensitivity and specificity of the test for central lesions in the setting of acute vertigo.23 Specifically, this was defined as new unilateral hearing loss as tested by finger rub. Although hearing loss often is associated with peripheral lesions such as labyrinthitis and Ménière’s disease, hearing loss with vertigo cannot rule out stroke and, in fact, increases the likelihood of stroke.23-25 Specifically, a stroke involving the anterior inferior cerebellar artery (AICA) can cause new hearing loss.8,23,25 Therefore, the finding of hearing loss should raise suspicion for central lesions and should be added to the HINTS examination.

Dix-Hallpike: If the history suggests BPPV, unique bedside testing should be performed. The Dix-Hallpike test is the test of choice. The Dix-Hallpike test is performed by having the patient seated on a stretcher or bed and positioned so that when the patient is supine, the patient’s neck can be extended 20°. To test the left ear, have the patient turn their head 45° to the left, then quickly move the patient from a sitting to a supine position, with the neck extended 20° and the head still turned 45° left. Wait 15 seconds, and if no vertigo or nystagmus occurs, sit the patient up and perform the same testing on the right side, with the head turned 45° to the right. A positive Dix-Hallpike test consists of a few seconds of latency followed by the onset of vertigo and nystagmus that typically lasts 15-30 seconds. The nystagmus is a combination of vertical upward and rotary.

Diagnostic Studies

Determining the need for diagnostics for vertigo is a critical task for emergency physicians, considering the wide variety of etiologies and likewise wide spectrum of disease severity. A thorough history and physical examination alone often will differentiate the various causes of vertigo. For instance, a short duration of symptoms exacerbated by head movement would suggest underlying BPPV. A HINTS examination also can help distinguish between peripheral and central causes of vertigo; however, imaging studies also can be employed to solidify the diagnosis as well. Unfortunately, biomarkers are not well established for diagnosis of diseases described here.

Diagnostic Algorithm

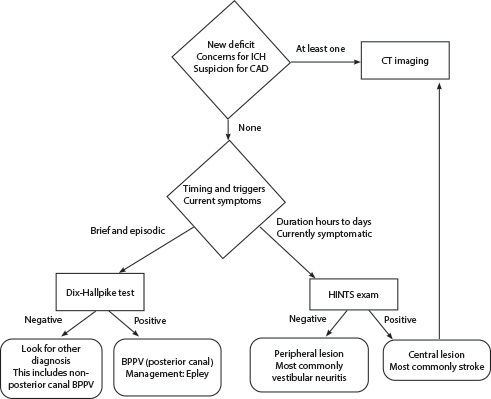

An overall algorithm for general vertigo is not well established; however, tests such as Dix-Hallpike and HINTS+ are useful tools in the ED to help differentiate causes of vertigo. As a general approach, identifying timing and differentiating central vs. peripheral causes is advantageous and can help narrow the differential. This is outlined in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Diagnostic Approach to Vertigo |

|

ICH: intracerebral hemorrhage; CAD: coronary artery disease; CT: computed tomography; BPPV: benign paroxysmal positional vertigo; HINTS: head impulse, nystagmus, test of skew |

Arguably, the first and most important step is to determine if vertigo is the presenting sign of a neurologic emergency, i.e., stroke. Concurrent symptoms such as focal neurologic deficits, inability to stand, ataxia, dysarthria, and aphasia all are concerning for an underlying stroke. Notably, the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) extensively used in the initial evaluation of strokes is not as sensitive for posterior circulation stroke, and a modified tool, POST-NIHSS, is more beneficial in the evaluation of patients with an NIHSS score < 10 and concerns for posterior stroke.26 Depending on timing, activating a stroke alert and the stroke team would be indicated. In this scenario, imaging is a vital step in the management of stroke and is described in the following section.

If concerns for stroke are low, a next plausible step is to determine the timing and trigger of vertigo. This is a key branch point because this will determine whether a Dix-Hallpike maneuver or HINTS exam would be appropriate. The fact that this is a branch point is important since an individual patient should not undergo both tests because the indications for performing the test are exclusive of one another.8 If vertigo is episodic and brief, a Dix-Hallpike maneuver can establish the diagnosis of BPPV. Otherwise, if the duration of vertigo is hours to days and still present on evaluation, a HINTS exam can help determine if the symptoms are due to a central or peripheral process. As described in the clinical features section, any one finding suggestive of a central process on HINTS exam should lead providers to assess further for central processes. The HINTS exam is particularly useful in the diagnosis of central lesions and should not be underestimated. The test is 100% sensitive and 96% specific for stroke and is in fact more sensitive than magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for stroke in early presentations of acute vertigo.27,28 If the HINTS exam is negative, this suggests a peripheral lesion, with the most common cause being vestibular neuritis.

This algorithm is not exhaustive and all-inclusive of the various causes of vertigo, and a complete history and examination still should be performed to pinpoint the underlying pathology. Common and key findings are described earlier in the clinical features section.

Imaging

Imaging has a significant role in the ED for diagnosis and evaluation of central causes of vertigo, considering the ramifications of missing a stroke or other central nervous system pathology. Computed tomography (CT) imaging often is the modality of choice by emergency physicians, given its accessibility and speed; however, in the setting of vertigo, and specifically posterior strokes, the diagnostic yield is low.29 Even in the setting of pathology, the sensitivity of CT imaging leads to a significant number of false negatives, e.g., missed strokes.30,31 Physicians should be careful about how to interpret MRI imaging. Although MRI increases the likelihood of making the diagnosis compared to CT, even MRI imaging can lead to a significant number of false negatives, particularly within 48 hours of symptom onset.30,31 As mentioned earlier, a thorough examination with the HINTS exam (with and without hearing exam) is more sensitive than even MRI.27,28

Although the diagnostic yield and sensitivity for pathology such as strokes is low overall for CT imaging in the setting of vertigo, CT imaging still is a necessary step in a few key presentations.8 Arguably, the most important role for CT imaging is to rule out hemorrhage. This often is the case in determining candidacy for thrombolytics for suspicion of stroke. In the setting of post-traumatic vertigo, CT imaging can be used to assess for intracranial hemorrhage when suspicion for bleed itself is high, while CT angiography will help evaluate for cervical artery dissection when evidence for this is present.

Other Diagnostic Tools

Tools such as nystagmography, electromyography (electronystagmography and vestibular evoked myogenic potentials), and audiometry also are used for the evaluation of vertigo but have little utility in the ED. Instead, patients who have follow-up with neurology may have these tests performed for further diagnostics. Briefly, nystagmography and vestibular evoked potentials are neurophysiologic tests that measure physiologic responses, such as eye movements (nystagmus) and cervical muscle response, to differentiate vestibular disorders.32,33 Audiometry is another adjunct to measure hearing loss in conditions such as Ménière’s disease.

Differential Diagnosis

Evaluation of other pathology that presents similarly to vertigo is important since patients often have difficulty describing the sensation of vertigo and other forms of dizziness.9 “Dizziness” often is the complaint patients use when being triaged in the ED for vertigo, but patients often use this term to describe many other different phenomena. Of patients who arrive to the ED with dizziness, a variety of disease states underlie their presentation, including BPPV, orthostatic hypotension, ischemic stroke, intracranial hemorrhage, seizure, and infection, among others. Notably, vertiginous causes still comprise most causes.34

Syncope and Presyncope

Syncope is the transient loss of consciousness due to transient hypoperfusion to the brain. Presyncope is a related phenomenon with the same pathophysiology and underlying causes minus the loss of consciousness. Vertigo is easily distinguishable from syncope since patients with vertigo do not classically lose consciousness; however, presyncope and vertigo can be difficult for patients and providers to distinguish.

Clinicians can differentiate presyncope from vertigo by focusing on features, such as timing, provoking factors, and associated symptoms, rather than qualitative features, such as room spinning vs. lightheadedness. When asking patients about the duration of symptoms, presyncope is almost always on the scale of seconds to minutes. Although vertigo can present on this timescale as well, longer durations of dizziness on the scale of hours prompts consideration of non-presyncopal causes. That is, a patient who comes in with dizziness lasting for days without relief is unlikely to be experiencing presyncope. Clinicians should carefully differentiate unrelenting dizziness for days vs. intermittent, short episodes of dizziness that have been ongoing for days, since the latter still can be a symptom of presyncope.

Just as defining the time line is important, identifying triggers also can help diagnose presyncope. For instance, dizziness from emotional stress, the sight of blood, or pain would suggest vasovagal etiology. Another trigger to consider is positional changes. Evaluating this trigger requires particular attention because changes in position will exacerbate both vertigo and orthostatic syncope. One key difference is that orthostatic syncope is sensitive to positional changes that decrease cerebral perfusion, such as transitioning from lying to standing. In contrast, positional changes that produce rotational changes, such as patients turning their heads or rolling in bed, would only trigger vertigo.

Differentiating presyncope and vertigo, therefore, requires careful history taking and characterization of concrete features, such as timing and triggers. Common etiologies of presyncope and syncope include vasovagal, orthostatic, psychogenic, and cardiogenic.

Disequilibrium

Disequilibrium is the sensation of imbalance or falling, particularly when walking, while vertigo is the false sensation of movement of the environment. This sensation can be very similar to vertigo, and the two often coincide. Patients with central causes of vertigo often will endorse vertigo and disequilibrium with gait instability. However, disequilibrium without vertigo suggests a different subset of pathology than previously discussed. Cervical spondylosis, for example, causes compression of the spinal cord leading to gait disturbances that can develop the sensation of disequilibrium often described similarly to vertigo. Parkinson’s disease also may produce the sensation of dizziness through disequilibrium, often early in the disease process.35

Psychiatric

Dizziness attributed to psychiatric disorders is one of the most common causes of dizziness.36 Further, one retrospective study suggests that psychiatric causes of dizziness can be more debilitating than other causes of dizziness. Specific psychiatric disorders that may manifest with dizziness include depression, major depression, generalized anxiety disorder, alcohol use disorder, and somatization disorder.36

Management

Management of vertigo is wholly dependent on the underlying cause of the patient’s symptoms. This may range from observation with as-needed maneuvering for BPPV to thrombolytics and intensive care unit (ICU) admission for large vessel occlusions in the posterior intracranial circulation. For most causes, vertigo will improve with symptomatic management alone.

Posterior Stroke

Posterior strokes are perhaps the most devastating cause of vertigo and require prompt and extensive interventions. Management is not significantly different from any other form of stroke. The most important consideration is timeliness for interventions, particularly thrombolytics and thrombectomy. The decision to proceed with these therapies often is made with consultation with neurology, especially considering the risks involved and continuous evolution of recommendations. Further management includes admission with the aim of stabilization, therapeutics, monitoring, and secondary prevention. This ideally will involve initial co-management with neurology and activation of the stroke team, if available. Ultimately, admission to a stroke center that is familiar with the care of such patients places them in the best position for favorable recovery.

As mentioned, one of the first and most critical steps is determining if patients qualify for definitive management with thrombolytics and/or thrombectomy. With posterior strokes, the determination of thrombolytics is similar to other forms of stroke but may vary to some degree by institution. The decision will hinge on the patient’s “last known normal,” since this will dictate whether the patient qualifies for the therapy. This is the best estimate to when clot pathology started and is used as the first determination for eligibility for clot treatment. Delayed administration of thrombolytics from this onset is associated with more complications, such as intracerebral hemorrhages and lower rates of benefits such as ambulatory function and home discharge. A cutoff of three hours is used for this, but it can be extended to 4.5 hours in certain circumstances.37 However, the patient’s last known well time often is hours before the actual onset of pathology if, for instance, a stroke occurs upon awakening in the morning from sleep. The WAKEUP trial suggests that, based on MRI findings, thrombolytics can be given if imaging indicates salvageable tissue allowing thrombolysis beyond 4.5 hours.38 Considering the risks involved in giving thrombolytic therapy, notable absolute contraindications exist and are noted in Table 3. Some discrepancies regarding these absolute contraindications may exist between hospitals, particularly in different countries. Additionally, multiple relative contraindications exist that also will help determine appropriateness of thrombolysis.

Table 3. Absolute Contraindications to Thrombolysis in Stroke |

|

SBP: systolic blood pressure; DBP: diastolic blood pressure; INR: international normalized ratio; |

Thrombectomy is another promising treatment option for patients presenting with clinically significant strokes. Importantly, this therapy remains an option past the typical 4.5 hours for thrombolysis. The MR CLEAN study was one of the largest that showed thrombectomy was superior to standard medical therapy when performed within six hours. A subsequent trial (DAWN) showed that extending the window out to 24 hours resulted in similar benefits, although with specific inclusion/exclusion criteria.39 One important caveat for these trials is that they focused on anterior circulation strokes. With posterior circulation stroke, the benefit of mechanical thrombectomy is equivocal. Although likely safe and feasible in posterior strokes, a recent study indicates that thrombectomy, specifically involving the basilar artery, does not provide significant improvement in outcomes when compared to standard medical therapy.40,41

Blood pressure management is important to balance cerebral perfusion and limit hydrostatic pressure that may lead to hemorrhagic conversion of ischemic stroke. No specific goal is set in guidelines for correction of hypotension, but physicians should be mindful of adequate tissue perfusion and administer fluids appropriately.8 Permissive hypertension up to 220/120 mmHg is recommended to promote cerebral perfusion; however, if thrombolytics will be administered, blood pressure should be controlled to 185/110 mmHg to avoid complications such as hemorrhagic transformation, and to 180/105 mmHg after administration.42,43 Common medications used for this indication include labetalol, nicardipine, and clevidipine.

BPPV

Management of BPPV is not as time-sensitive as stroke management, given the lack of significant long-term complications. Management often can be performed easily by patients on their own after some degree of instruction. For patients experiencing posterior canal BPPV, the Epley maneuver is the first-line treatment and can be performed quickly by the patient, often with immediate results. To perform this maneuver, either with the help of a provider or after instruction, the patient should turn their head toward the affected ear at a 45° angle in a sitting position and recline to a supine position. When in this position, the patient should have their head extended past horizontal to about 20° to 30°. A pillow underneath the neck may help achieve this hyperextension. Hold this position for about 30 seconds. (Note that this may recreate symptoms of vertigo since the steps so far are the same as the Dix-Hallpike maneuver used to diagnose BPPV. Nonetheless, have the patient push through this dizziness to achieve resolution of symptoms.) Next, the patient should turn the head 90° away from the affected ear so that the head is facing 45° in the direction opposite of the affected ear. Hold this position for 30 seconds. Next, have the patient rotate their entire body, including the head, 90° in the direction opposite of the affected ear so that they are lateral decubitus and with the face toward the ground at a 45°angle, and the affected ear is pointing up. Hold this position for 30 seconds. Finally, have the patient sit up from this position, and the Epley maneuver will have been completed.

If the patient does not experience relief after multiple attempts and attempting on both sides, the patient may be experiencing BPPV from a different canal. For horizontal canal BPPV, the Gufoni maneuver likely will provide relief of symptoms. If instead the patient is experiencing vertigo from anterior canal BPPV, the deep head hanging maneuver may prove therapeutic. Seldom, patients should use pharmacologic agents for BPPV.8

Pharmacotherapy

Medications that are readily available and can provide quick relief are an easy option for symptomatic management of vertigo. This option generally is reserved for symptoms that have lasted hours to days, since vertigo from processes such as BPPV likely will quickly resolve and not require pharmacotherapy. When selecting an agent for relief of vertigo, several options are available with varying mechanisms.

Antihistamines are the classic option for management of vertigo. Both H1 and H3 antihistamines are options for addressing vertigo. These include meclizine (H1) and betahistine (mostly H3). Specifically with betahistine, this medication may be doubly beneficial since it also may help facilitate vestibular compensation, with one study showing prolonged effects even after discontinuation.44 Betahistine is only available in Europe and other parts of the world, but not in the United States. Notably, H2 antihistamines such as famotidine are ineffective at managing vertigo.

Benzodiazepines are another class of medications that often are used for symptomatic management of vertigo in the ED. A recent review suggests that antihistamines may be the better option considering better symptomatic relief when compared to benzodiazepines.45

Special consideration should be made to minimize duration of pharmacotherapy. Antihistamines, benzodiazepines, and antipsychotics all have significant side effect profiles that become more prominent with long-term use. Additionally, these drugs have a high risk of delirium in older patients.

Vestibular Rehabilitation

Another useful modality for management is vestibular rehabilitation. This is not likely an option for patients in the ED, but it may be useful for patients as follow-up from the ED visit. Rehabilitation involves various exercises incorporating eye, neck, and body movements that improve vestibular function through central nervous system compensation.46,47 Compared to standard therapy, vestibular rehabilitation provides significant improvement.48 Vestibular rehabilitation has evolved with technology as well, with some patients benefitting from the use of virtual and augmented reality as part of their therapy.49

Other Therapies

Considering the wide gamut of causes of vertigo, a complete review of all management options cannot be fully covered here. Additionally, many of these therapies have limited use since they are specific to a single cause of vertigo. For instance, vestibular migraines are treated similarly to other migraines rather than typical treatments for vertigo. The exact pharmacologic agents will vary by provider but may include acetaminophen, ibuprofen, antiemetics, steroids, and/or fluids. The management of Ménière’s disease is highly variable, but the mainstay of treatment is symptom management with antihistamines as well as use of thiazide diuretics in confirmed cases.50 Patients should follow a low-sodium diet and should be referred to an ear, nose, and throat specialist, since intratympanic injections of corticosteroids or gentamicin may help decrease the frequency of attacks.8,19 Surgical interventions also are an option for Ménière’s disease, and other causes, including perilymph fistulas, also may benefit from operative management with emergent referral for those with acute hearing loss.51

Additional Aspects

Older Patients

Vertigo is notably more prevalent in older populations, with one study showing a 50% prevalence by age 85 years and a strong correlation between prevalence of vertigo with age.52 The pathology behind this increase is likely multifactorial but importantly includes degenerative changes of the vestibular system also referred to as presbystasis.53,54 Although the exact pathophysiology of presbystasis is unknown, one study suggests that it may be related to decreases in production of otoconia.55 Other factors that contribute to vertigo and overall dizziness in older populations include polypharmacy, cardiovascular disease, and degenerative changes in other systems, such as proprioception and vision. Many of the drugs found on the medication list of older patients can cause ototoxicity, including ibuprofen, furosemide, and losartan. Ototoxic drugs are discussed in the section on etiology. Degenerative changes of other systems, such as vision and proprioception, do not cause vertigo themselves but may compound the overall sensation of dizziness.

Summary

Vertigo can be a complicated complaint for emergency medicine physicians to manage. The differential for this is broad, ranging from benign processes, such as BPPV, to more devastating causes, such as posterior strokes. Therefore, making the correct diagnosis is critical to appropriately manage patients presenting with vertigo, since patients with posterior strokes require specific and timely management. Patients often have difficulty qualitatively describing the sensation of vertigo, complicating the diagnosis, yet many physicians rely heavily on the patient’s description of the experience of dizziness to diagnose or rule out vertigo.56 Instead, physicians should focus on more concrete and reliable features, such as timing, duration, and triggers. Awareness of new diagnostic tools, such as HINTS+ that incorporates hearing loss and POST-NIHSS that considers posterior circulation symptoms, also will help. With a more broad and up-to-date understanding of vertigo and its causes, management of this complaint does not have to be a daunting endeavor.

REFERENCES

- Gerlier C, Hoarau M, Fels A, et al. Differentiating central from peripheral causes of acute vertigo in an emergency setting with the HINTS, STANDING, and ABCD2 tests: A diagnostic cohort study. Acad Emerg Med 2021;28:1368-1378.

- Hanna J, Malhotra A, Brauer PR, et al. A comparison of benign positional vertigo and stroke patients presenting to the emergency department with vertigo or dizziness. Am J Otolaryngol 2019;40:102263.

- Stanton M, Freeman AM. Vertigo. In: StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2023:1-243.

- Dougherty JM, Carney M, Hohman MH, Emmady PD. Vestibular dysfunction. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2023.

- Palmeri R, Kumar A. Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; Jan. 3, 2022.

- Jensen JK, Hougaard DD. Incidence of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo and course of treatment following mild head trauma—Is it worth looking for? J Int Adv Otol 2022;18:513-521.

- Vanni S, Pecci R, Edlow JA, et al. Differential diagnosis of vertigo in the emergency department: A prospective validation study of the STANDING algorithm. Front Neurol 2017;8:590.

- Tintinalli JE, Ma OJ, Yealy DM, et al. Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide, 9th ed. 2020.

- Newman-Toker DE, Cannon LM, Stofferahn ME, et al. Imprecision in patient reports of dizziness symptom quality: A cross-sectional study conducted in an acute care setting. Mayo Clin Proc 2007;82:1329-1340.

- Kim HJ, Park JH, Kim JS. Update on benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. J Neurol 2021;268:1995-2000.

- Smith T, Rider J, Cen S, Borger J. Vestibular neuronitis. In: StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; July 11, 2022.

- Mahmud M, Saad AR, Hadi Z, et al. Prevalence of stroke in acute vertigo presentations: A UK tertiary stroke centre perspective. J Neurol Sci 2022;442:120416.

- Zhu Z, Li Q, Wang L, et al. Risk factors and risk model construction of stroke in patients with vertigo in emergency department. Comput Math Methods Med 2022;2022:2968044.

- Alwood BT, Dossani RH. Vertebrobasilar stroke. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; May 2, 2022.

- Kim JS, Newman-Toker DE, Kerber KA, et al. Vascular vertigo and dizziness: Diagnostic criteria. J Vestib Res 2022;32:205-222.

- Benjamin T, Gillard D, Abouzari M, et al. Vestibular and auditory manifestations of migraine. Curr Opin Neurol 2022;35:84-89.

- Hilton DB, Shermetaro C. Migraine-associated vertigo. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; Aug. 19, 2022.

- Lempert T, Olesen J, Furman J, et al. Vestibular migraine: Diagnostic criteria. J Vestib Res 2012;22:167-172.

- Koenen L, Andaloro C. Meniere disease. In: StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; Feb. 13, 2023.

- Sarna B, Abouzari M, Merna C, et al. Perilymphatic fistula: A review of classification, etiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Front Neurol 2020;11:1046.

- Altissimi G, Colizza A, Cianfrone G, et al. Drugs inducing hearing loss, tinnitus, dizziness and vertigo: An updated guide. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2020;24:7946-7952.

- Lui F, Tadi P, Anilkumar AC. Wallenberg syndrome. In: StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; Oct. 21, 2022.

- Newman-Toker DE, Kerber KA, Hsieh YH, et al. HINTS outperforms ABCD2 to screen for stroke in acute continuous vertigo and dizziness. Acad Emerg Med 2013;20:986-996.

- Chang TP, Wang Z, Winnick AA, et al. Sudden hearing loss with vertigo portends greater stroke risk than sudden hearing loss or vertigo alone. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2018;27:472.

- Lee H. Audiovestibular loss in anterior inferior cerebellar artery territory infarction: A window to early detection? J Neurol Sci 2012;313:153-159.

- Alemseged F, Rocco A, Arba F, et al. Posterior National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale improves prognostic accuracy in posterior circulation stroke. Stroke 2022;53:1247-1255.

- Kattah JC, Talkad AV, Wang DZ, et al. HINTS to diagnose stroke in the acute vestibular syndrome: Three-step bedside oculomotor examination more sensitive than early MRI diffusion-weighted imaging. Stroke 2009;40:3504-3510.

- Tehrani AS, Kattah JC, Mantokoudis G, et al. Small strokes causing severe vertigo: Frequency of false-negative MRIs and nonlacunar mechanisms. Neurology 2014;83:169-173.

- Wasay M, Dubey N, Bakshi R. Dizziness and yield of emergency head CT scan: Is it cost effective? Emerg Med J 2005;22:312.

- Chalela JA, Kidwell CS, Nentwich LM, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography in emergency assessment of patients with suspected acute stroke: A prospective comparison. Lancet 2007;369:293-298.

- Lawhn-Heath C, Buckle C, Christoforidis G, Straus C. Utility of head CT in the evaluation of vertigo/dizziness in the emergency department. Emerg Radiol 2013;20:45-49.

- Young AS, Lechner C, Bradshaw AP, et al. Capturing acute vertigo: A vestibular event monitor. Neurology 2019;92:e2743-e2753.

- Dorbeau C, Bourget K, Renard L, et al. Vestibular evoked myogenic potentials. Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis 2021;138:483-488.

- Navi BB, Kamel H, Shah MP, et al. Rate and predictors of serious neurologic causes of dizziness in the emergency department. Mayo Clin Proc 2012;87:1080-1088.

- Kwon KY, Park S, Lee M, et al. Dizziness in patients with early stages of Parkinson’s disease: Prevalence, clinical characteristics and implications. Geriatr Gerontol Int 2020;20:443-447.

- Kroenke K, Lucas CA, Rosenberg ML, et al. Causes of persistent dizziness. A prospective study of 100 patients in ambulatory care. Ann Intern Med 1992;117:898-904.

- Saver JL, Fonarow GC, Smith EE, et al. Time to treatment with intravenous tissue plasminogen activator and outcome from acute ischemic stroke. JAMA 2013;309:2480-2488.

- Thomalla G, Simonsen CZ, Boutitie F, et al. MRI-guided thrombolysis for stroke with unknown time of onset. N Engl J Med 2018;379:611-622.

- Nogueira RG, Jadhav AP, Haussen DC, et al. Thrombectomy 6 to 24 hours after stroke with a mismatch between deficit and infarct. N Engl J Med 2018;378:11-21.

- Meyer L, Stracke CP, Jungi N, et al. Thrombectomy for primary distal posterior cerebral artery occlusion stroke: The TOPMOST Study. JAMA Neurol 2021;78:434-444.

- Langezaal LCM, van der Hoeven EJRJ, Mont’Alverne FJA, et al. Endovascular therapy for stroke due to basilar-artery occlusion. N Engl J Med 2021;384:1910-1920.

- Gross H, Grose N. Emergency neurological life support: Acute ischemic stroke. Neurocrit Care 2017;27(Suppl 1):102-115.

- Jauch EC, Saver JL, Adams HP, et al. Guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke: A guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2013;44:870-947.

- Parfenov VA, Golyk VA, Matsnev EI, et al. Effectiveness of betahistine (48 mg/day) in patients with vestibular vertigo during routine practice: The VIRTUOSO study. PLoS One 2017;12:e0174114.

- Hunter BR, Wang AZ, Bucca AW, et al. Efficacy of benzodiazepines or antihistamines for patients with acute vertigo: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Neurol 2022;79:846-855.

- Zhang S, Liu D, Tian E, et al. Central vestibular dysfunction: Don’t forget vestibular rehabilitation. Expert Rev Neurother 2022;22:669-680.

- Suman NS, Rajasekaran AK, Yuvaraj P, et al. Measure of central vestibular compensation: A review. J Int Adv Otol 2022;18:441-446.

- Tokle G, Mørkved S, Bråthen G, et al. Efficacy of vestibular rehabilitation following acute vestibular neuritis: A randomized controlled trial. Otol Neurotolo 2020;41:78-85.

- Heffernan A, Abdelmalek M, Nunez DA. Virtual and augmented reality in the vestibular rehabilitation of peripheral vestibular disorders: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep 2021;11:1-11.

- Ahmadzai N, Cheng W, Kilty S, et al. Pharmacologic and surgical therapies for patients with Meniere’s disease: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. PLoS One 2020;15:E0237523.

- Furhad S, Bokhari AA. Perilymphatic fistula. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; Sept. 26, 2022.

- Jönsson R, Sixt E, Landahl S, Rosenhall U. Prevalence of dizziness and vertigo in an urban elderly population. J Vestib Res 2004;14:47-52.

- Ciorba A, Hatzopoulos S, Bianchini C, et al. Genetics of presbycusis and presbystasis. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol 2015;28:29-35.

- Swain SK, Anand N, Mishra S. Vertigo among elderly people: Current opinion.J Med Soc 2019;33:1.

- Walther LE, Westhofen M. Presbyvertigo-aging of otoconia and vestibular sensory cells. J Vestib Res 2007;17:89-92.

- Stanton VA, Hsieh YH, Camargo CA, et al. Overreliance on symptom quality in diagnosing dizziness: Results of a multicenter survey of emergency physicians. Mayo Clin Proc 2007;82:1319-1328.

Vertigo can be a complicated complaint for emergency medicine physicians to manage. The differential for this is broad, ranging from benign processes, such as BPPV, to more devastating causes, such as posterior strokes.

Subscribe Now for Access

You have reached your article limit for the month. We hope you found our articles both enjoyable and insightful. For information on new subscriptions, product trials, alternative billing arrangements or group and site discounts please call 800-688-2421. We look forward to having you as a long-term member of the Relias Media community.