Emergency Care of the Medically Complex Pediatric Patient

Authors

Ercole Anthony Favaloro, MD, Emergency Medicine Physician, St. Tammany Parish Hospital, Covington, LA

Rachel Cramton, MD, FAAP, Pediatric Palliative Care, University of Arizona COM/Banner University Medical Center, Diamond Children's Medical Center, Tucson

Peer Reviewer

Steven M. Winograd, MD, FACEP, Attending Emergency Physician, Keller Army Community Hospital, West Point, NY

Executive Summary

- Children with special healthcare needs (CSHCN) are those who have or are at increased risk for chronic physical, developmental, behavioral, or emotional conditions and who require health and related services of a type or amount beyond that required by children generally.

- Often, CSHCN will have vital signs that do not align with those that are normal for their age. Abnormal vital signs always should be taken as a sign of critical illness until proven otherwise. However, it is important to obtain baseline vital signs from a family member, caretaker, or electronic medical record (if available), since CSHCN often may have seemingly abnormal vital signs that are normal for them.

- CSHCN also are at higher risk of physical abuse. It is important to maintain a high degree of suspicion in these cases for physical exam evidence or histories inconsistent with a patient’s injuries or degree of developmental ability.

- Children with ventriculoperitoneal shunt malfunctions/failures may present in various ways, including altered mental status, irritability, difficulty feeding, headache, emesis, fever or erythema, or tenderness over the shunt tract in the scalp. Many patients (30% to 51%) will present with shunt failure within the first year of placement.

- A common and serious complication is shunt infection. It has an occurrence rate of 11.7% within 24 months of uncomplicated initial shunt placement. The majority (> 90%) of infections occur within six months of initial shunt placement or revision. Most commonly, the pathogen is a result of colonization at the time of placement.

- Shunt malfunction is a neurosurgical emergency. Once imaging studies have identified the cause of the shunt malfunction and provided definitive evidence of malfunction, consult with a neurosurgeon to provide definitive treatment for these patients. It is important to get them involved early if the patient is well-known to the surgeon, has evidence of impending herniation, or has a clinical history consistent with prior malfunctions.

- Tracheostomy complications occur in 15% to 19% of patients. Complications may present as a primary problem with the device itself or secondary to an underlying medical condition. The most common and concerning ones that will arise in the emergency department (ED) are dislodgement, obstruction, infection, and bleeding.

- Infections are a common complication for tracheostomy patients given the fact that the tube provides direct entry and colonization of the trachea itself. These patients often will have chronic colonization with many types of bacteria throughout their airway. They often will present with fevers, increased mucus production, or increased oxygen requirements. There may be overlying skin changes, such as erythema, warmth, and induration concerning for cellulitis at the stoma site. The patient may have an infection of the trachea itself (tracheitis), or the patient may have a resultant pneumonia or mediastinitis. In this patient population, as opposed to the patient with an intact airway, they may present with a more indolent and subacute infection requiring a higher degree of clinical suspicion.

- Any patient who presents with bleeding from the tracheostomy site merits a high degree of suspicion for tracheoinnominate fistula. Even if the patient has bleeding that has resolved at the time of presentation, it still is concerning for a sentinel bleed in the setting of fistula formation, and the patient should undergo bronchoscopy. If the patient is stable at presentation, imaging studies can be attempted, but early surgical consultation is recommended even prior to imaging. If bleeding is significant on presentation, the first attempt to occlude bleeding should be to over-inflate the cuff. This is successful in ~85% of cases of tracheoinnominate fistula.

- Gastric tube malfunctions may manifest as dislodgement, migration, leakage of gastric contents/nutritional feeds, local tissue irritation, granulation tissue formation, tube obstruction, intestinal obstruction, bleeding, erosion/ulceration, and infection. Patients may present with nonspecific findings such as nausea, emesis, feeding intolerance, irritability, fever, abdominal distention, and abdominal pain. Dislodgement is by far the most common cause for ED presentation.

Children with special healthcare needs require an individualized approach based on their unique situations. Acute care providers must be familiar with the special devices, potential complications, and evaluations necessary for children with these devices. Early involvement of pediatric specialists may be necessary to provide optimal care to these children. The authors discuss many aspects of the care of children with special healthcare needs to enhance their care and optimize outcomes.

— Ann M. Dietrich, MD, FAAP, FACEP, Editor

Introduction

Patients with special healthcare needs may present unique problems for emergency medicine providers because they often are more resource-intensive, require the use of more specialized testing, and may merit special considerations when determining how to approach them. Medically complex pediatric patients may not receive the same level of care as their more straightforward counterparts, secondary to providers’ lack of experience or training related to their care. “Children with special healthcare needs (CSHCN) are those who have or are at increased risk for chronic physical, developmental, behavioral, or emotional conditions and who require health and related services of a type or amount beyond that required by children generally.”1

It is important to recognize CSHCN and know how to effectively triage and treat them; they are becoming more prevalent in our communities. Approximately 13.9% to 15.6% of children in the in the United States have special healthcare needs as of 2013.2 As medical advancements improve, so will the number of CSHCN. CSHCN have four times the number of hospitalizations yearly, 1.5 times the number of emergency department (ED) visits, and expenses that are three times higher than the general pediatric population.3 The majority of CSHCN are seen in general EDs throughout the country, as opposed to pediatric-specific EDs.4 Of note, 69.4% of the general pediatric population seeking emergency care in the United States were evaluated in EDs that see less than 15 pediatric patients per day.5 This highlights the need for all practitioners to be familiar with medically complex pediatric patients and how best to approach them.

Although CSHCN often will present to the ED for reasons similar to their peers, they also have some distinctly nuanced presentations. A study performed in Italy in 2020 found that the most common reason for admission from the ED in the complex pediatric patient was respiratory related, followed by gastrointestinal symptoms, which is similar to the general pediatric population in Italy. Furthermore, they noted that the complex population had higher visits for neurologic complications compared with the general population. Traumatic injuries are less common in the complex population, but device malfunction is a relatively common complaint.3 Overall, the presenting complaints for CSHCN will be similar to the general population — but with some caveats that lend to the nature of the child. Namely, this population has a higher percentage of medical device dependency and a higher likelihood of a neurologic problems than the general population.

These statistics demonstrate the need to educate providers caring for CSHCN patients. It behooves providers to have access to the information necessary to troubleshoot medical devices and be familiar with indications to consult with specialists. Early recognition of issues related to chronic medical problems may facilitate consultation and appropriate transfer to a facility with a higher level of care. Conversely, identification of simple treatable issues in this population may allow the child to be cared for in a community facility, saving the family a potentially costly transfer and better using our healthcare resources.

Initial Management of Children with Special Healthcare Needs

The initial management of any child, regardless of how medically complex they are, follows the same approach. As emergency medicine providers, an evaluation cannot progress until the patient’s airway, breathing, and circulation (ABC) have been evaluated and addressed. However, once initially stabilized, if necessary, there are several considerations for children with complex healthcare needs compared with those who are otherwise developmentally normal.

Often, CSHCN will have vital signs that don’t align with those normal for their age. Abnormal vital signs always should be taken as a sign of critical illness until proven otherwise. However, it is important to obtain baseline vital signs from a family member, caretaker, or electronic medical record (if available), since CSHCN often may have seemingly abnormal vital signs that are normal for them. This can provide reassurance in the face of abnormal vital signs on a monitor so long as they are within the patient’s baseline. Children with certain structural congenital heart disease can have oxygen saturations between 70% to 80% at baseline, and they may even decompensate if pushed to 100% with supplemental oxygen. However, in the absence of well-documented vital signs outside of the normal range, abnormal vital signs should be interpreted as a sign of serious illness.

Patients with complex medical needs often will be on multiple medications, have extensive surgical histories, and likely will have multiple conditions present that are related to or are sequelae of the initial disease process. It will be important to obtain a thorough review of their medications, including any recent changes, additions, or discontinuations. Ideally, a family member will have the most recent medication list present, but if not, it may be necessary to track down a copy from the pediatrician’s office, consultant’s office, pharmacy, or hospital electronic medical records. It will be helpful to have a basic timeline of prior surgeries, especially as it relates to the patient’s presenting complaints.

Physical exams are particularly important in CSHCN, but there are notable nuances and pitfalls. These children often are nonverbal or are not at a developmental stage in which they can provide a reliable history. CSHCN may not have normal physical exam findings at baseline, or they may have a condition that impedes a normal physical exam. For example, a 4-year-old with cerebral palsy may not walk at baseline, with contractures present on physical exam. It will be important to take these findings into account because the family member or caretaker present may be the only source of a reliable history. It is more important to rely on those presenting with the patient to also provide an accurate description of what is physically normal for the patient.

CSHCN also are at higher risk of physical abuse. It is important to maintain a high degree of suspicion in these cases for physical exam evidence or histories inconsistent with a patient’s injuries or degree of developmental ability. A clinical report from 2007 noted that 872,000 children were victims of abuse or neglect in 2004, and 7.3% of all victims were victims with a disability (in only 36 of 50 states reporting on disabilities). There are many factors that play into this, including the fact that many of these children will be nonverbal at baseline, making communication more difficult, as well as the increased economic, physical, and emotional burden experienced by them and their families.6

These patients also may have complex social situations. Treatment of chronic conditions is exceedingly expensive. As such, parents may have difficulties affording medications, therapies, or doctor’s visits if insurance does not cover it. It is important to take into consideration the financial burden if a missed therapy or medication is a potential cause for a patient’s presentation. Furthermore, these children often will need around-the-clock care that can be exhausting for parents. Many children with complex medical needs are in foster care for several reasons, including the difficulty of caring for them. For these reasons, it can be very helpful to involve a social worker early in the care of the patient while in the ED. Recent research has demonstrated the benefit of having social determinants of health screenings for this population.7 A social worker can help to provide resources for the patient and family member to help improve their care and potentially avoid future ED visits.

On Device Malfunctions

Many children with special healthcare needs require the use of special devices to treat their condition or provide support. The most common devices that emergency medicine providers are likely to see are enteral tubes, ventriculoperitoneal (VP) shunts, and tracheostomies. There are many others that providers may see that are out of the scope of this article, such as continuous positive airway pressure machines, arteriovenous fistulas, cochlear implants, nerve stimulators, and pacemakers, to name a few. Children with special needs often will present with a complication arising from their devices. Emergency medicine providers should have a reasonable understanding of how they work, the potential complications associated with them, how to treat those complications, and know when to consult specialists.

Ventriculoperitoneal Shunt Malfunctions

Indications

A ventricular shunt is a common device placed to relieve intracranial pressure (ICP) in cases of hydrocephalus. This often is a result of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) obstruction, overproduction, or underabsorption. A patient may have a congenital cause for placement, such as in neural tube defects, Arnold-Chiari malformation, Dandy-Walker syndrome, aqueductal stenosis, or arachnoid cysts. Patients may have an acquired cause, such as a brain tumor, meningitis, intraventricular hemorrhage secondary to prematurity, idiopathic intracranial hypertension, or a traumatic brain injury.

It is important to recognize there are different types of CSF shunts. Overall, they consist of a proximal catheter inserted into the ventricle, a reservoir, a one-way pressure valve, and a distal catheter.8 The reservoir often is used for sampling and pressure management. The distal catheter may insert into the peritoneum (the most common being ventriculoperitoneal), the lung pleura (ventriculopleural), the atrium (ventriculoatrial), or the gall bladder (vetriculocholecystic).8,9 The valve may be programmable or fixed. The benefit of programmable valves is that they can be manipulated by an external device and, thus, will not necessarily require revision by a neurosurgeon.

Complications and Differential Diagnosis

Children with VP shunt malfunctions/failures may present in various ways, including altered mental status, irritability, difficulty feeding, headache, emesis, fever or erythema, or tenderness over the shunt tract in the scalp. Many patients (30% to 51%) will present with shunt failure within the first year of placement. Most commonly, shunt failure arises from a mechanical cause, such as discontinuity, obstruction, or migration of the shunt tubing. However, infection is another very common reason.10-12

Disconnections and fractures of the tubing may be a result of trauma or the patient’s physical growth, typically occurring in the distal tubing. Tubing may become calcified or scarred down in the tissue, which increases the likelihood of a disconnection. This often can occur from increased mobility of a patient and stretching of the tubing because of repeated movement. Patients who can communicate may describe a “popping” sensation.13 Localized swelling along the shunt tract may be seen, along with signs of increased ICP.9

Obstructions may occur as a result of a proximal or distal cause. This may be a result of clogging of the tubing from tissue or cells (i.e., macrophages, glial cells, choroid plexus, brain parenchyma, or blood) or a local inflammatory reaction. Valve obstruction is considerably less common but can occur because of the same culprits in proximal tubing obstruction. Distal obstructions can result from anything that would increase downstream pressure as well as obstruction from the aforementioned cellular and tissue debris, such as from a pleural effusion in the case of a ventriculopleural shunt. Cases of distal obstruction tend to present later than proximal obstruction.9,14 In the case of ventriculoperitoneal shunts, intra-abdominal pressure, such as with severe constipation, abscess, or pseudocyst formation, also can cause shunt failure. Pseudocyst formation is thought to be in relation to a low-grade inflammatory process, but the exact etiology is unclear.15-18

Migration of the tubing can occur through organ tissue in the area where the distal end of the shunt is located. This can also be a result of the child’s growth. It may occur from the proximal site with migration out of the ventricle or out of the distal site, in particular from the cavoatrial junction, but can occur from any distal site.9 In the literature, shunt migration has been documented to occur through the bowel, anus, gall bladder, stomach, liver, scrotum, bronchi, and heart. Perforation is a major concern in these cases, in addition to failure of the shunt.9,19-23

A common and serious complication is shunt infection. It has an occurrence rate of 11.7% within 24 months of uncomplicated initial shunt placement.24 The majority (> 90%) of infections occur within six months of initial shunt placement or revision.11 Most commonly, the pathogen is a result of colonization at the time of placement. Common pathogens are skin and enteric flora, with coagulase-negative staphylococci being the most common, along with others, such as methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus, and gram-negative bacilli. However, multidrug-resistant bacteria, such as methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus epidermidis, are becoming more prevalent.11, 25-28 Risk factors associated with an increased infection rate include a history of shunt revision (most common), young age, prematurity, prior infection, and the etiology of hydrocephalus, to name a few.25,29

Other causes of shunt failure may be a result of over- or underdrainage. The literature seems to demonstrate that fixed shunts have a higher risk of over- or underdrainage, obstruction, and revision in relation to their programmable counterparts, while programmable shunts seem to demonstrate a higher degree of intrinsic failure.30-33 Slit ventricle syndrome (SVS), or “normal volume hydrocephalus” or “noncompliant ventricle syndrome,” is another cause of shunt failure. This condition lacks a consistent definition, however. It occurs in chronically shunted patients and can present with small ventricles on neuroimaging. This is thought to be related to a siphoning effect of the distal catheter site. This condition may or may not have symptoms present. When present, common symptoms will be headache, emesis, and often a degree of altered mental status.9,34 However, presentation may be subtle, and symptoms may be nothing more than vision changes.35

History and Physical Exam

Presentation of shunt complications is variable, may initially be subtle, and may be difficult to distinguish between acute obstruction or chronic progression. Therefore, it is important to maintain a high index of suspicion for shunt complications. Early assessments should focus on identifying signs of increased ICP or active evidence of impending herniation. Often, these patients will be nonverbal or may be too altered to give any reliable information. As with any complex pediatric patient, there are certain questions to consider related to their hardware. Providers should ask about when the shunt was placed, who the surgeon who placed the shunt was, the type of shunt (programmable or fixed), and where the shunt terminates. Remember that, although less common, the P in VP shunt may indicate pleural placement and is not always indicative of peritoneal placement. It will be important to take note of any prior revisions, shunt infections, or other complications. Parents often will be hyper-vigilant with their medically complex children and will have a good idea of prior presenting symptoms related to their shunt failure.

Older children commonly will present with somnolence, headache, and emesis. Drowsiness is by far the best clinical predictor of shunt malfunction. Headache and vomiting are less predictive.36 Patients also may present with seizures or increased seizure activity if they experience frequent seizures at baseline. They may develop cranial nerve palsies, blurred vision, or diplopia. Patients may complain of back and neck pain in cases of tubing disconnection or fractures. Abdominal pain can be a prominent complaint in patients with pseudocyst formation or constipation causing obstruction. The patient may have signs of local inflammation along the scalp or swelling along the neck or chest. In a worst-case scenario, the patient may present or develop signs of herniation with Cushing’s triad of hypertension, bradycardia, and irregular respirations.12,16,37

On initial assessment, take note of the vital signs and the patient’s overall mental state at presentation. When performing a physical exam, it is a good idea to palpate along the area of tubing to feel for any local tenderness, disconnections, or swelling. Visually inspect the area for exposure of the tubing through the skin, which is a nidus for infection. Pay attention to evidence of localized cellulitic changes, if present. Take note of pupil size, bulging of the fontanelle (if open), and head circumference; these patients often will have previous head circumference measurements obtained at prior ED or clinic visits to compare.

Diagnostic Studies

There are several important diagnostic studies to evaluate for shunt malfunction. An initial study that can be obtained relatively quickly is a shunt series. This standardized series of X-rays will obtain images along the length of the shunt to evaluate for obvious physical problems with the shunt itself. This will include X-rays of the skull, neck, chest, and abdomen. It may identify a shunt disconnect, kinking, or migration.8,38

Noncontrast head computed tomography (CT) probably is the most-used study in evaluating for shunt malfunctions. It can be used to determine the degree of ventriculomegaly, transependymal flow of CSF, herniation, and other signs of hydrocephalus.8,39 One disadvantage of CT is the radiation exposure; however, obtaining “thick cut” images will allow for appropriate assessment of ventricular size and can eliminte up to 90% of the radiation dose.39 When reviewing images, they should be read in context of previously obtained images. If needed, a CT with intravenous (IV) contrast of the chest or abdomen can be obtained to identify if there has been hollow organ perforation or pseudocyst formation.8,16

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), if available, also can be a helpful alternative to a CT scan. The benefit of MRI over CT is the lack of radiation exposure, which can be important in this population, which has a higher incidence of CT scans and fluoroscopic procedures over its lifetime. In addition to information about ventricular size and transependymal flow, MRI can evaluate for complications such as ventriculitis and abscess formation. Of note, if performing an MRI in a patient with a programmable shunt, the shunt will need to be reset following the procedure. This will require the on-site evaluation of a neurosurgeon or other provider with the capability to reprogram a shunt.8,38 Most institutions will have protocols in place for obtaining a rapid scan, CT, or MRI for rapid identification of shunt malfunction, with a focus of a rapid, timely diagnosis of shunt dysfunction.

Ultrasound (US) is another imaging modality that has some future potential as a diagnostic tool in assessing the amount of ICP in patients with shunt failure. It currently is used to assess the optic nerve sheath diameter in adults to determine the level of papilledema and concern for ICP in the right clinical setting. Axial images can be obtained using a linear array probe while the patient is supine. One of the challenges seen in pediatric patients is having them remain still with eyes closed to obtain transbulbar images. The benefits of US are the lack of radiation exposure and the speed with which these images can be obtained in an experienced provider’s hands. However, at this time, US has not yet been validated in this patient population.40,41

If the results of radiographic imaging do not demonstrate evidence of ventricular dilation, and symptoms of a malfunction are present, a high degree of suspicion still must be maintained for device malfunction. Up to 9% of patients will present without radiographic evidence.42 Any patient with signs or symptoms of a potential shunt malfunction should have consultation with a neurosurgeon, who will review imaging and coordinate care the of the child. Also of note, evidence of collapsed ventricles may be present in children with chronic over-drainage, resulting in obstruction. In these cases of SVS, the imaging may be misinterpreted as normal and will still require an evaluation and treatment by a neurosurgeon.8,9,33

Occasionally, patients will require a tap of the shunt, generally by a neurosurgeon. A shunt tap can yield information about infection with CSF studies. It also can gauge the pressure through the system. The scalp is prepped with povidone-iodine solution or ChloraPrep, and the shunt reservoir is accessed with a 23- or 25-gauge butterfly needle. Generally, CSF should return spontaneously.43 If not, gentle aspiration can be attempted.

Anything requiring greater than 1 mL of back pressure is concerning for poor flow. Using a manometer, total pressure can be assessed. The manometer should be held above the patient’s ear while they are supine. A pressure of greater than 25 cm H2O is indicative of obstruction. Overall, poor flow is concerning for an obstruction more proximal to the valve.44-46 Of note, this should only be performed after discussion with a neurosurgeon and in cases of immediate, life-threatening ICP. There currently is no consensus in the literature of just one method for performing the shunt tap, so a review of the procedure should be performed prior to actually performing the procedure itself.

Treatment

Shunt malfunction is a neurosurgical emergency. It is important to identify the etiology quickly. Once imaging studies have identified the cause of the shunt malfunction and provided definitive evidence of malfunction, consult with a neurosurgeon to provide definitive treatment for these patients. It is important to get them involved early if the patient is well-known to the surgeon, has evidence of impending herniation, or has a clinical history consistent with prior malfunctions. These patients often will need a shunt revision, but in some cases, simply reprogramming the shunt can resolve the problem. If there is a concern for hollow viscus perforation, a consult to the pediatric surgeon may be necessary.34,47

In cases of infection, the patient will require IV antibiotics and may require removal of the shunt with a complete revision once the infection has resolved. Empiric therapy should be initiated with vancomycin, to include MRSA coverage, and cefotaxime or ceftriaxone. There are several studies that have demonstrated the effectiveness of intrathecal antibiotics, in addition to IV antibiotics, owing to the improvement in drug delivery by bypassing the blood-brain barrier. However, there currently is no consensus on the routine use of the intrathecal route. Therefore, in the ED, broad-spectrum IV is the preferred route.26-28

Disposition

Patients with VP shunt malfunctions ultimately require neurosurgical intervention and should be transferred to a facility with those capabilities. Generally, they will require admission to a pediatric intensive care unit (ICU) for frequent neurologic checks. In cases where a patient has unremarkable imaging studies but persistent symptoms, it is reasonable to admit them for observation, given their high risk for complications and the subtle presentation of early malfunctions.39,48

Tracheostomy Malfunctions

Indications

Tracheostomies are one of the earliest procedures recorded —there are illustrations depicting the procedure in Egypt from as early as 3600 B.C.49,50 In pediatric patients, there are many indications for placement. In most cases, they are placed to assist with ventilation in patients with malformations of the airway, such as those with Treacher Collins syndrome, patients who require prolonged ventilatory support in the case of cardiopulmonary dysfunction in prematurity, and those who have neuromuscular disorders, such as cerebral palsy, to name a few.51-53 Over the past 35 years, the indications for tracheostomy placement have changed. Rarely are emergent tracheostomies required for pediatric patients with acute airway obstruction secondary to infectious or traumatic causes. Although the rate of pediatric tracheostomy placement is decreasing overall, improvements in the care of medically complex patients mean that children with tracheostomies are living longer and are more prevalent in our communities and EDs.52,54,55

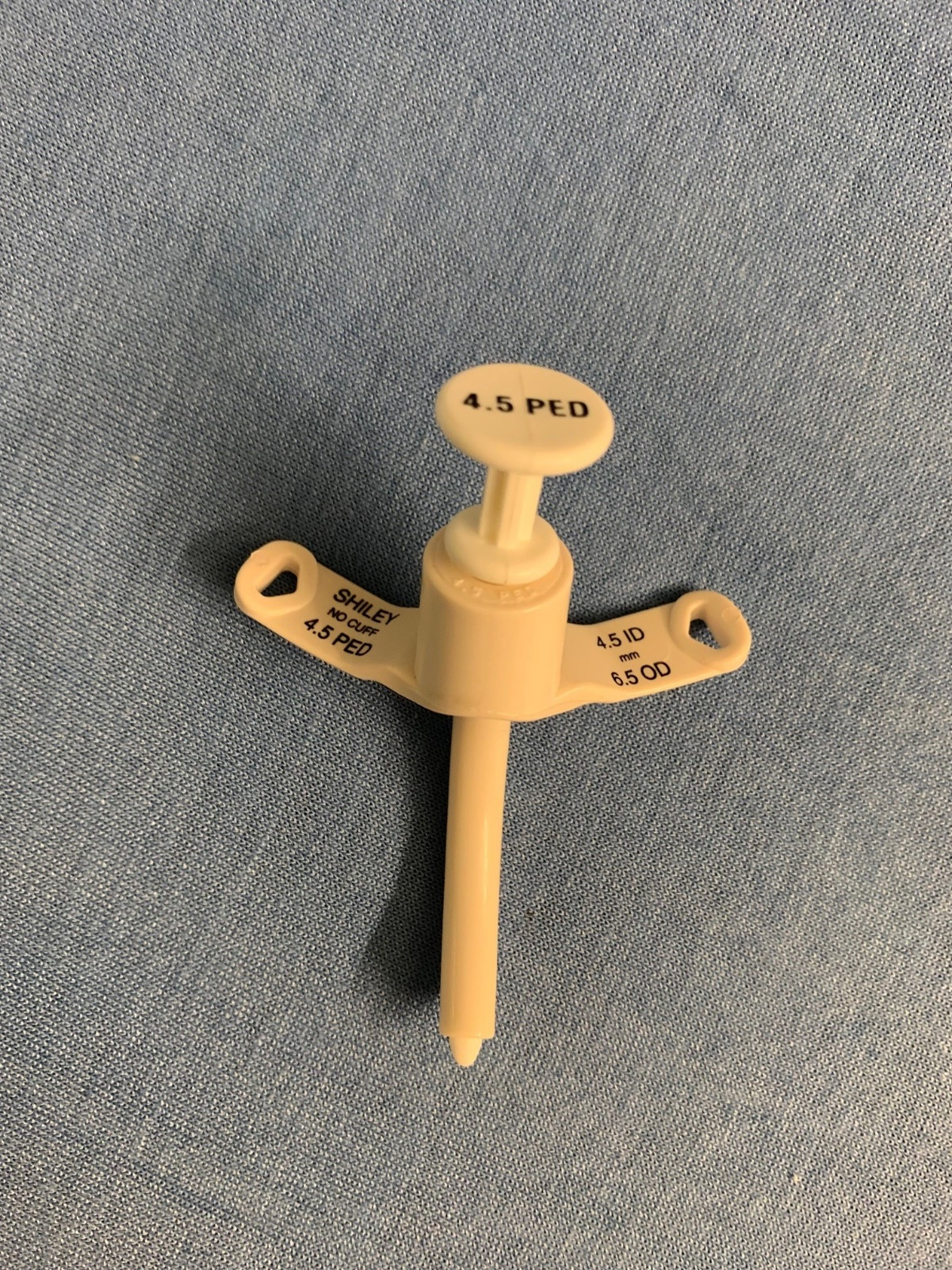

Although emergent placement is rare today, this is a common device seen in CSHCN, and it is important to recognize. The bulk of the tracheostomy tube consists of the faceplate, shaft (outer cannula), and inner cannula. (See Figure 1.) In the pediatric population, the tracheostomy tube will not have an inner cannula. At the end of the shaft there may be a balloon indicating a cuffed vs. uncuffed trach, the latter of which does not have a balloon. Uncuffed tubes are preferred in the pediatric population, given the risk for injury to the trachea. In the pediatric population, fenestrated tubes are not available; however, if the patient is near adult size, this still will be a factor to consider. The two most common brands encountered are Shiley and Bivona in the pediatric population.51,56,57 When evaluating a trach tube, it is important to note how the tube is sized. The size of the device is determined in millimeters by the inner diameter (ID) not the outer diameter (OD). Typically, sizes will range from 2.5 mm to 6.5 mm. It also will be important to note the length of the device. For patients weighing less than 5 kg, neonatal tracheostomy tubes are employed. They are shorter in length than pediatric tubes, but the diameter remains the same. For example, a neonate may have a 3.0 mm cuffed Bivona that is 30 mm in length.51,56

Figure 1. Pediatric Tracheostomy Tube |

|

Courtesy of Dr. Ercole Anthony Favaloro. |

Complications and Differential Diagnosis

Tracheostomy complications occur in 15% to 19% of patients. Complications may present as a primary problem with the device itself or secondary to an underlying medical condition.58,59 These patients may present with an acute rapid clinical decline, or they may present with a more subacute decompensation with increased O2 requirements. There are many potential complications that can occur with tracheostomy tubes, but the most common and concerning ones that will arise in the ED are dislodgment, obstruction, infection, and bleeding.60,61

Dislodgement and obstruction are common occurrences. Dislodgment can be life-threatening, especially if the family is not prepared at home with appropriate supplies and training to replace the tube or in cases of an immature, recently placed tracheostomy. Obstruction may occur because of mucus plugging (more common) or from granulation tissue obstructing the tube (less common). Mucus plugging can occur frequently in the setting of respiratory illness. Granulation tissue will occur because of persistent irritation of either the skin at the site of insertion or the mucosa within the trachea. Other complications that can arise include the creation of a false lumen resulting from traumatic injury during a tracheostomy change, which leads to inadequate oxygenation and ventilation of the patient.59,61,62 As with VP shunts, the patient may simply outgrow the size of the current tracheostomy tube. Patients likely will need a planned procedure to increase the size of the tracheostomy every two years. If not replaced, children often will have low-pressure ventilation alarms triggered on their home vent or have frequent nocturnal desaturations.63

Infections are a common complication for tracheostomy patients given the fact that the tube provides direct entry and colonization of the trachea itself. These patients often will have chronic colonization with many types of bacteria throughout their airway.64,65 They often will present with fevers, increased mucus production, or increased oxygen requirements. There may be overlying skin changes, such as erythema, warmth, and induration concerning for cellulitis at the stoma site. The patient may have an infection of the trachea itself (tracheitis), or the patient may have a resultant pneumonia or mediastinitis. In this patient population, as opposed to the patient with an intact airway, they may present with a more indolent and subacute infection requiring a higher degree of clinical suspicion.

Generally, bacterial tracheitis is less aggressive in the tracheostomy patient than those with an intact airway. The most common causative organisms are S. aureus, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Haemophilus influenzae. More often than not, tracheitis in this population will present with a concurrent pneumonia or bronchial infection.60,64-66 In all, 88% of these patients develop a lower respiratory tract infection within one year of tracheostomy placement.67

The other potentially serious complication is from bleeding. This is the most common early complication following tracheostomy placement. Bleeding may occur because of too-frequent deep suctioning that causes repeated trauma to the trachea, inadequate humidification of the airway, tracheitis, or disruption of granulomatous tissue irritating friable mucosa. Granulation tissue at the stoma site is friable and will bleed easily, but it is not life-threatening.50,51 A rare but life-threatening bleed that can occur in these patients is a tracheoinnominate fistula. Its incidence in the literature is reported to be up to 1%, but some studies report up to 4.5%.68-70 It usually occurs within three to four weeks following initial surgical placement.69 This usually will present with a sentinel bleed (a relatively minor bleed that often will have stopped by time of presentation) before progressing to significant hemoptysis in ~50% of cases.59,68 Even after the tracheostomy has matured, patients still can experience long-term complications because of prolonged tracheostomy. Mucosal necrosis may occur from overinflated cuffs, a malpositioned tracheostomy tube, or from repeated movement of the tube causing repeated tissue injury. Over time, this can lead to scarring and tracheal stenosis, weakening the tracheal cartilage.51

History and Physical Exam

When initially assessing these patients, providers must first cover the ABCs, with airway being the most critical in scenarios of tracheostomy malfunction. It is important to recognize patency of the patient’s airway, which can be difficult in a nonverbal patient. Look for signs of respiratory distress (tachypnea, hypoxia, retractions, etc.). Listen for gurgling, coughing, or choking. This may indicate obstruction or blood in the airway. Listen for breath sounds and look for retractions or other indicators of an increased work of breathing. Providers cannot move on to obtaining further history or a more thorough exam before first establishing a definitive airway if the patient is in distress and has evidence of failure of their current device.57,71

Once the patient is initially stabilized, it is important to gather further information from patients or, more likely, their parents or caretakers. Providers must determine when the tracheostomy tube was placed. If placed fewer than seven days prior, the tube is considered to be immature. Before then, it is at higher risk of complications, especially false tract creation with replacement.50,56 Providers must also gather information regarding who placed the tube, the size and brand of the tube, any previous complications, the indication for tube placement (e.g., a cuffed tube was placed as opposed to an uncuffed tube in a patient who is at high risk of aspiration), and whether there was an attempt to replace the tube at home prior to arrival. In the setting of potential infectious etiology, it can be useful if the parent has information regarding any previous sputum culture results or prior antibiotic regimen used to treat infection.

Diagnostic Studies

Chest X-rays are helpful in determining whether there is evidence of pneumonia, pneumothorax, and the degree of chest wall expansion. Laboratory studies usually are not necessary, although a venous blood gas can be helpful in determining the patient’s degree of respiratory distress. In cases of concern for tracheitis or pneumonia, a viral respiratory panel and tracheal aspirate cultures can be obtained to help the inpatient and consulting teams determine the exact pathogen and susceptibilities.

A bronchoscopy can be performed by a pediatric pulmonologist, otolaryngologist (ENT), or pediatric surgeon to assess the degree of bleeding, patency of the tube, and degree of granuloma or stenosis present. In cases of innominate fistula or significant bleeding from tumor or local airway trauma, CT angiography of the neck can help provide more information. However, in the setting of bleeding, diagnostic therapies have only about 20% to 30% sensitivity, and, in the setting of significant bleeding, patients often are taken to the operating room based off of clinical history and presentation alone.68,72 Therefore, providers must retain a high degree of suspicion in these patients and consider early surgical consultation.

Treatment

As noted previously, establishing a definitive airway in these patients is critical in their initial treatment. If time allows and information is obtained prior to arrival about the patient’s condition, it can be useful to consult a pediatric ENT and have them at bedside, along with available equipment. This generally is not the case, so having the room set up with suction devices, a bag-valve mask (BVM), and a respiratory therapist is a good start.

Oxygenating the patient will be the next most important step and may require some initial troubleshooting. Attempts to oxygenate and ventilate the patient using a BVM connected to the tracheostomy should be attempted first in patients with respiratory distress. Assess for improvement in O2 saturations, end-tidal capnography color change on the colorimeter, and appropriate chest rise. If not achieved, an attempt at oxygenating the patient with the BVM via the oro-nasal route can be performed, but be sure to occlude the stoma site if performing positive pressure ventilation from above. When providing respiratory support with BVM via the oral-nasal route, deflate the cuff (if present) to allow for ventilation. For patients who have mild respiratory distress and hypoxemia, a trach mask can be placed over the tracheostomy or stoma. Be sure to used humidified oxygen to avoid drying out sensitive mucosa and causing bleeding.

Troubleshooting the tracheostomy tube itself starts with suctioning the tube with a catheter in cases of obstruction. Albuterol and a few milliliters of sterile saline along with humidified air can be used as adjuncts, which will aid in breaking up mucus plugging that may be present.

If attempts to clear the tube are unsuccessful, replacing the tracheostomy tube is the next step. A nonfunctioning or obstructed tube offers no benefit to a clinically deteriorating patient. If available, a flexible fiberoptic laryngoscope can be useful in determining patency of the tube. However, this requires familiarity with device operation and a stable, cooperative patient. Flexible laryngoscopy should not delay removal of the tube if a patient is decompensating. An attempt should be made to replace the tube with the same size tube to establish a definitive airway. It is important to have backup equipment present at the bedside including a tracheostomy tube a half-size smaller, an appropriately sized endotrachael tube and equipment necessary for orotracheal intubation.57,71 A bedside exchange can be attempted if the tract is mature. In cases of an immature tract, do not attempt to blindly replace the tube.56,57 Instead, remove the malfunctioning tracheostomy tube and manage the patient’s airway with an open stoma until surgical help arrives. Tube replacement in an immature tract has a high risk of complications, including airway trauma, bleeding, and false lumen formation. This should be attempted by a specialist, ideally in the operating room. In these situations, it is important to establish an airway above the level of the tracheostomy. Orotracheal intubation, although potentially difficult in patients with airway anomalies, facial malformations, or significant tracheal stenosis, should be attempted first. In many cases use of a flexible fiberoptic laryngoscope can be very helpful in obtaining access from above in this patient population.60,71,73

Any patient who presents with bleeding from the tracheostomy site merits a high degree of suspicion for tracheoinnominate fistula. Although rare, it is life-threatening when present. Even if the patient has bleeding that has resolved at the time of presentation, it still is concerning for a sentinel bleed in the setting of fistula formation, and the patient should undergo bronchoscopy.73 If the patient is stable at presentation, imaging studies can be attempted, but early surgical consultation is recommended even prior to imaging. If the patient presents with bleeding, determine if the source is superficial from the stoma site because of local irritation or cellulitis or if it is coming from the airway itself. If bleeding is significant on presentation, the first attempt to occlude bleeding should be to over-inflate the cuff. This is successful in ~85% of cases of tracheoinnominate fistula. However, if bleeding continues, an attempt should be made at orotracheal intubation. Once this is established, remove the tracheostomy tube and insert a gloved finger into the airway to provide digital compression of the fistula between your finger and the patient’s anterior airway.68-71

If there is concern for infection, the patient should be treated with appropriate antibiotic therapy. If the child is ill-appearing in the case of suspected tracheitis or mediastinitis, empiric IV therapy should be initiated using vancomycin for MRSA coverage plus a third-generation cephalosporin, such as cefotaxime, ceftriaxone, ampicillin-sulbactam, or a fluoroquinolone for penicillin-allergic patients.64,66,74 If concurrent aspiration pneumonia is suspected or if the child does not improve on the aforementioned empiric coverage, consider adding clindamycin or metronidazole for anaerobic coverage.74 If suspected or known colonization with Pseudomonas is present, consider empiric coverage that will provide appropriate coverage.67 Currently there are no standard guidelines for treatment of respiratory tract infections in tracheostomy patients. Important considerations are any previous culture results from prior tracheal aspirates that can be used to help guide therapy.75,76 In terms of cellulitis involving the stoma, therapy should be directed at skin flora. Oral therapy can be used to treat mild infections with amoxicillin-clavulanate or clindamycin. If ill-appearing, broad-spectrum IV therapy should be started and consideration for more serious infections considered, such as cervical necrotizing fasciitis or mediastinitis. Topical nystatin can be initiated if fungal cellulitis is suspected.67

Disposition

Generally, these patients will require definitive intervention from a specialist. Early surgical consultation is recommended because the potential for decompensation and difficulty obtaining definitive airway access is high. If the patient is presenting to an ED that does not have a pediatric ICU or the appropriate surgical specialist, they will require transfer to a facility that can provide these services after they have been stabilized. Rarely, these children will be suitable for discharge home, although it may be reasonable in conjunction with specialist recommendations.

Enteral Tube Malfunctions

Indications

Many patients require feeding via an enteral tube if adequate nutrition or medications cannot safely be provided orally. This may be the result of increased metabolic demands, such as the case in cystic fibrosis or a congenital heart disease; because of an oral-motor dysfunction in patients with neurologic issues, such as anoxic brain injury or an anatomic malformation, such as a vascular ring malformation; or because of an inability to tolerate medications, certain diets, or an overall oral aversion in conditions such as trisomy 21 or autism. Whatever the reason may be, these patients are dependent on an enteral route for nutritional supplementation and medication administration.

The patient may have any of one of many different types of enteral feeding tubes. These may include nasogastric tubes (NG tubes), nasoduodenal tubes (ND tubes), gastric tubes (G tubes), jejunal tubes (J tubes), and gastrojejunal tubes (GJ tubes). NG and ND tube placement often are a short-term solution, since they come with a higher risk of dislodgment and aspiration. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tubes are placed for longer-term supplementation. Patients are placed under general anesthesia or conscious sedation to receive PEG tubes. Alternatively, G tubes can be placed open or laparoscopically. G tubes may have a short length of external tubing associated with them, or they may be button-type tubes, such as the Mic-Key or mini-G tubes, which sit much flatter along the skin, making it more difficult to become dislodged. J or GJ tubes need to be placed under fluoroscopic guidance by interventional radiology (IR) or gastroenterology (GI). These tubes are beneficial in patients who are at higher risk of aspiration, as seen in patients with delayed gastric emptying or severe gastrointestinal reflux. In these types of tube systems, medications often are provided via the G port, and continuous feeds are provided via the J port. As with ND tubes, bolus feeds are not possible through J or GJ tubes and cause considerable patient discomfort and the potential for osmotic diarrhea if attempted.77-80

Complications and Differential Diagnosis

Gastric tube malfunctions may manifest as dislodgment, migration, leakage of gastric contents/nutritional feeds, local tissue irritation, granulation tissue formation, tube obstruction, intestinal obstruction, bleeding, erosion/ulceration, and infection. Patients may present with nonspecific findings such as nausea, emesis, feeding intolerance, irritability, fever, abdominal distention, and abdominal pain. Dislodgement is by far the most common cause for ED presentation. Sixty percent of all ED visits for G tube complaints are because of dislodgment.81 Dislodgment occurs in 65% of patients within five years of tube placement.81,82 Obstruction of the tube can result from kinking of the tubing and material clogging the tube. Medications and feeds can obstruct the tubing if the tube is not flushed regularly.77,83,84 Gastrocolocutaneous fistula formation is a rare early complication of PEG tube placement. This occurs because of the transverse colon migrating in front of the anterior portion of the stomach during PEG placement, causing a gastrocolic or gastrocolocutaneous fistula.78,85

Although peritonitis is a rare complication following G tube placement, it is a major one. It can occur 0.5% to 6.6% of the time in PEG placement and 2.5% of the time in percutaneous retrograde tube placement.86,87 It can occur after initial placement or replacement of a G tube. The patient often will present with emesis, fever, irritability, and abdominal rigidity. This can occur from a correctly placed tube with leakage directly into the peritoneal cavity or from leakage from an incorrectly placed tube that has created a false tract. Occasionally, abdominal perforation or fistula formation may lead to leakage of abdominal contents.60,86

Infection concerns generally are related to cellulitis surrounding the stoma site. This presents with redness around the stoma site and may not have fevers associated with it. Drainage of pus, induration, and tenderness all may be present. Discharge of pus should be differentiated from normal minimal stomal discharge and leakage of abdominal contents. The most common causative agents are S. aureus, Plasmodium species, Escherichia coli, Enterobacter cloacae, Streptococcus, Lactobacillus, and Bacteroides species. Fungal infections may occur and present with a pinpoint rash around the stoma site.88 However, more rare conditions may arise, such as abscess formation, peritonitis, or septic shock. Of note, in any child who has a G or GJ tube presenting with pulmonary complaints, aspiration pneumonia should be considered as possible source.77

Other complications include peristomal granulation tissue formation. This is seen in up to 70% of patients. Leakage of gastric contents can occur because of balloon rupture or deflation, which can lead to local tissue irritation. This can lead to localized redness and possibly bleeding, which can worsen granuloma tissue formation.77,89

History and Physical Exam

When evaluating patients with enteral feeding tube complications, providers should obtain several pieces of information. It is important to know when the tube was placed, who placed the tube (pediatric surgeon, IR, GI), what type of tube it is (PEG, GJ, mushroom tip, button, etc.), and the length. If dislodged, it is important to know how long the tube has been out of the body, since the stoma has a tendency to close over time if left open. It is worth asking caregivers if they brought an extra tube with them to the ED — parents of complex children often plan for every possibility. Hospitals will not necessarily have multiple brands and sizes of G tubes, and it will be beneficial if the parent or caretaker has an extra with them. Many times, parents are provided with an extra tube for dislodgment scenarios. It also is important to note the indication for placement and whether the patient has had any prior complications.

When performing the physical exam, assess the stoma site, including removing any dressing present. Evaluate for bleeding, the presence of purulent drainage, and leakage of contents. Assess whether there is abdominal distention present greater than the patient’s baseline or if the abdomen is firm, rigid, or tender, indicating more concerning signs of peritonitis.

Diagnostic Studies

Rarely are diagnostic studies needed in the evaluation of gastrointestinal tube malfunction. If there is concern for peritonitis or abscess, when the patient is stable, consider obtaining a CT or MRI with contrast of the abdomen and pelvis to further evaluate the situation. An abdominal X-ray with water-soluble contrast can be used to evaluate or confirm tube placement if replacing the tube was difficult or if it remains unclear whether it is in correct position following replacement. On the whole, imaging has not been shown to be more effective in confirming placement and, in fact, has been shown to increase the length of the ED stay for patients.82,83 A newer modality for assisting and confirming tube placement using point-of-care US has been shown through several studies to be effective.90-92 However, the speed and accuracy of this modality will depend on the skill of the operator. Nevertheless, with more research, this may aid in a shorter length of stay, more successful placement, and a decrease in complications on bedside replacement in the future.

Treatment

In cases of dislodgement, it is important to know how long the tube has been out. The longer the tube stays out and the more recently the tube was placed, the more risk there is for early closure of the stoma site. The stoma site will begin to close within a few hours of the tube being out. The parent or caretaker should be trained on how to replace the tube at home, but if they are uncomfortable with the procedure or lack the proper equipment, they may present to you for help. If placed less than four to six weeks prior, the tract is considered immature and is at higher risk of false lumen creation when replacing it. Therefore, as with tracheostomy tubes, you should consult your specialist prior to replacing it because, most times, the specialist likely will prefer to do it themselves.

To replace a tube, time is of the essence. If the parent has a replacement that was brought with the patient, attempt to use that first. It is a good idea to call for another tube brought to the ED from the hospital’s material supply as well as the same tube type but one size smaller in case the stoma has narrowed. If unsuccessful with the attempts or a replacement G tube is not readily available, use a Foley catheter to keep the stoma patent. It is important to use a generous amount of sterile lubricant on the end of the tube when replacing it. Applying tension along the skin of the stoma will aid in advancement. There will be some mild resistance when replacing the tube, especially if the patient is crying or bearing down. However, the tube should pass through the stoma with some ease following the initial bit of resistance.

If encountering significant resistance or if the patient appears to be in significant pain, providers should stop and make the attempt again with a smaller-sized tube.46,77,93 If there is a need to use a smaller tube, serial dilation can be undertaken in the ED. This is achieved by placing the largest Foley catheter allowable in the stoma. Then, successive replacement of the Foley should be attempted with the next Foley size up until the size of the prior tube is reached. There is no designated length of time the Foley needs to stay in prior to attempting dilation. This can be attempted to save the family a hospitalization and visit from the surgeon.81 Generally speaking, research has shown that misplacement in the ED and risk of complication is low, which would suggest that this is something that every ED provider should feel comfortable attempting.82,83,94

Once a tube has been successfully replaced, there are several ways to confirm placement. If the tube was placed with little effort and gastric contents are aspirated, this may be all the confirmation needed. However, depending on physician comfort and degree of difficulty in replacing the tube, pH testing can be used on gastric aspirate. Alternatively, ~10 mL of water-soluble contrast (e.g., gastrografin) can be placed through the tube and an upright abdominal X-ray obtained. If contrast is observed within the stomach and intestine, this indicates successful placement.88,93

If the patient had a J or GJ tube in place that became dislodged, quickly place a Foley catheter in the stoma to preserve the stoma tract and size. However, these patients will require definitive placement of a new GJ tube with visualization to ensure that the jejunal portion is placed correctly. In these scenarios, it is beneficial to obtain an early consult from the service who placed the tube originally to facilitate quick replacement.

A clogged enteral tube can be a common complication, especially with thick feeds, bulking agents, and medications. There are a few methods of treating clogged enteral tubes. Pancreatic enzymes can be inserted into the tube and allowed to dwell for 15 minutes. Alternatively, there is some older literature suggesting that carbonated liquid can be used to help dissolve a clog, which was seen to be more effective when followed up with pancreatic enzymes.95,96 When working with a clogged G, it must be replaced. If a GJ tube remains clogged, a consult to the service that placed it will be necessary. Obstruction of GJ tubes is more common because of the length of the J portion and diameter of the tubing, which is predisposed to becoming clogged.

If infection is suspected, it should be treated with the appropriate antibiotics. Cellulitis often can be treated with oral antibiotics, and the patient can be discharged from the ED. If the patient is ill-appearing and there is concern for abscess formation or peritonitis, then the service that initially placed the tube should be consulted, and the patient should be admitted to the pediatric service appropriate for the level of clinical concern. Current recommendations from the Infectious Diseases Society of America include initiating broad-spectrum IV therapy of a single-agent carbapenem, piperacillin-tazobactam, or combination therapy of metronidazole plus either an aminoglycoside or a third- or fourth-generation cephalosporin, such as cefotaxime, ceftriaxone, or cefepime.97

Topical agents can be applied for treatment of local inflammation, irritation, and bleeding. Zinc oxide, magnesium hydroxide/topical sucralfate, and antibiotic ointment can be applied around the stoma site along with frequent dressing changes with 2 x 2-inch gauze pads. Treat fungal infections with hydrocortisone/nystatin cream. If there is concern for extension of spread or evidence of systemic infection, oral antibiotics covering skin flora, such as clindamycin or cephalexin, should be considered.88 The balloon also should be assessed for its integrity; it may be a cause of gastric content leakage. The position of the tube itself also should be checked, since it may have migrated. Make sure to pull the tube so the balloon rests along the anterior stomach wall. Push the retention disc down near the skin to help prevent further movement. Silver nitrate can be applied to any granulation tissue that has formed.77,88

In children with enteral tube placement receiving continuous feeds in the setting of a metabolic disorder, it may be appropriate to check basic metabolic labs and start dextrose-containing fluids while tube problems are being resolved. Of note, when restarting a specialized feed is in question, if a parent brings in the patient’s home feeds or providers need to discuss with the pharmacist or nutritionist, it is important to consult the patient’s geneticist or whomever may have prescribed a particular formula for nutritional support.

Disposition

These patients often are appropriate for discharge home after resolution of the presenting complaint.94 When a G tube is successfully replaced and functional, the patient generally is appropriate for discharge. Patients who are dependent on a J or GJ tube for nutrition and hydration must have the jejunal portion correctly replaced prior to discharge. If this cannot be secured, they may require admission for IV hydration until the J or GJ tube can be replaced. In cases of local cellulitis, treatment can be initiated in the ED, and if the patient is clinically well-appearing with knowledgeable caregivers and reliable follow-up, they can be discharged home as well.

If there is concern for a more serious infection, it often is appropriate to have the patient admitted to a pediatric service or, if critically ill, to a pediatric ICU. In cases where tube replacement was unsuccessful, if a temporary tube, such as a Foley or smaller-diameter tube is placed, or if the tract is immature, the patient will require admission or transfer to have the tube replaced.

Palliative Care

Many CSHCN, despite their additional needs, are expected to live long, reasonably healthy lives. However, others have conditions that likely will result in their deaths before reaching adulthood. Because of this variability, CSHCN may or may not have advanced directives in place. Although do-not-resuscitate or allow natural death orders are not as common in pediatric patients as they are in adults, it still is something that should be approached when these patients present to the ED. While generally unnecessary for a child presenting for a simple complaint, when a complex patient presents acutely ill, it is reasonable to discuss the matter. There is a dearth of literature about palliative care in the pediatric ED. When these conversations do arise, they can be overwhelming to providers and parents. Given the increase in medical technologies and in the amount of CSHCN being seen in the ED, these conversations likely will become more common.

Time often is a major limiting factor in how effective providers are in communicating with families in the ED. Given the medical complexity of CSHCN patients and with how frequently they present within the healthcare system, spending an appropriate amount of time with the family to communicate well becomes increasingly more important. Caring for the medically complex patient in the ED can be a daunting task. Often, there is a lack of resources or trained staff available to appropriately care for medically complex pediatric patients. This can add to the tension a provider feels in addition to the time management needed to take care of other patients. This is why, in addition to the medical treatment of the patient, effective communication is crucial in these scenarios.

Being able to leverage resources, such as social workers and child life therapists, can help promote good communication with these patients and their families. It is important to take additional time to address the family’s goals of care, which will benefit the patient and also may affect their ultimate disposition.98

Conclusion

Medically complex pediatric patients can be difficult to take care of in the ED. Their conditions may be nuanced, and information leading to their diagnosis may be more difficult to tease out. However, it is important to remember the basics that all patient’s evaluations need to begin with the ABCs. From there, be able to recognize how the CSHCN may differ from patients without special healthcare needs and what additional information will benefit in diagnosis and treatment. Recognize that there are many complex medical conditions that may require differing medical devices for treatment — and which devices are most common. Be able to troubleshoot what may be causing a device malfunction and know how to treat it. Consider reaching out to pediatric and surgical sub-specialists early for help and consider early transfer to a higher level of care once stable. Lastly, take time with the patient and family members to gain the appropriate information needed to treat them in line with the patient’s goals of care.

References

To view the references, visit https://bit.ly/3Xl0guB.

Children with special healthcare needs require an individualized approach based on their unique situations. Acute care providers must be familiar with the special devices, potential complications, and evaluations necessary for children with these devices. Early involvement of pediatric specialists may be necessary to provide optimal care to these children. The authors discuss many aspects of the care of children with special healthcare needs to enhance and optimize outcomes.

Subscribe Now for Access

You have reached your article limit for the month. We hope you found our articles both enjoyable and insightful. For information on new subscriptions, product trials, alternative billing arrangements or group and site discounts please call 800-688-2421. We look forward to having you as a long-term member of the Relias Media community.