By Michael H. Crawford, MD, Editor

A large Australian database study has shown that, because of the much larger number of patients without severe aortic dilatation, almost all fatal dissections occur in individuals with non-severely dilated aortas — the so-called aortic paradox.

Paratz ED, Nadel J, Humphries J, et al. The aortic paradox: A nationwide analysis of 523,994 individual echocardiograms exploring fatal aortic dissection. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 2024; May 29. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jeae140. [Online ahead of print].

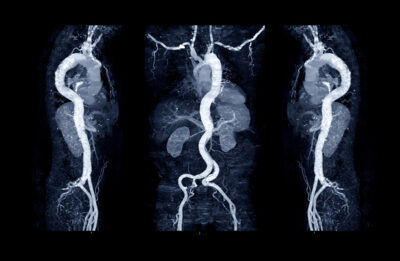

Recent publications have highlighted the fact that many patients who have aortic diameters below the surgical cutoff of 5.5 cm and without genetic aortopathy experience acute thoracic aorta dissection or rupture. Thus, these investigators analyzed the National Echocardiographic Database of Australia (NEDA), which is a highly diverse population of equal sex distribution with > 1 million inpatient and outpatient echocardiograms in 630,000 adults. In 2019, this registry was linked to the National Death Index (NDI) of Australia.

In patients with more than one echocardiogram, the most recent one was used. Patients with prior aortic valve replacement or aortic surgery were excluded. Aorta diameters were taken from the sinuses of Valsalva or the proximal aortic root and categorized as normal (< 4 cm), mild dilatation (4 cm to 4.4 cm), moderate (4.5 cm to 5.5 cm), and severe > 5.5 cm. In subgroups where height or weight was reported, indexed measurements were assessed. Blood pressure was obtained from the echocardiographic report and categorized as hypertension (systolic blood pressure [SBP] > 140 mmHg) or severe hypertension (SBP > 180 mmHg or diastolic BP > 110 mmHg). The primary outcome was death caused by aortic dissection or ruptured aneurysm.

After excluding those with no aorta measurements, the final cohort consisted of 524,994 unique patients with a median age of 64 years of whom 52% were men. Normal aorta diameter was found in 88% of patients, mild dilatation was found in 10% of patients, moderate dilatation was found in 1.9% of patients, and severe dilatation was found in 0.1% of patients. After a median follow-up of seven years, 899 patients died of aortic dissection (median age 77 years, 60% men). The mean time from echocardiogram to dissection was 11 years. Compared to those with normal aortic diameters, death caused by dissection was increased with mild aortic dilatation (odds ratio [OR], 3.05; 95% confidence interval [CI], 2.61-3.56); moderate (OR, 4.0; 95% CI, 3.02-5.30), and severe (OR, 28.72; 95% CI, 18.44-44.72). However, because of the greater number of those without severe dilatation, 98% of fatal dissections occurred in those without severe dilatation. Indexing for height or body surface area did not change the results.

Of the 5,248 patients with bicuspid valves (1%), only five died of dissection. If the 38% of patients with severe dilatation who underwent surgery are considered dead at the time of surgery, the death rate in this group increases from 2% to 24%. The authors concluded that since severely dilated proximal thoracic aortas account for only 2% to 24% of fatal dissections, we need better risk predictors in those without severe dilatation.

COMMENTARY

This aortic paradox has been seen in some smaller studies, but not in others. Some have shown a much higher rate of dissection among those with severely dilated aortas, but they measured aortic size after dissection, and it is known that dissection can cause abrupt aortic expansion. Should we move the indication for surgery to a lower diameter?

There have been observational studies from aortic disease centers that suggest we should consider 4.5 cm or 5.0 cm as the indication for surgery. However, even mild aortic enlargement demonstrated a threefold increase in the risk of fatal dissection in the Paratz study. The risk of surgery vs. benefit would be hard to demonstrate at 4 cm to 4.5 cm. Perhaps in an ideal world of a viable percutaneous approach to reducing the size of the aorta, this could make sense. Thus, at this point, the authors suggest exploring better ways to risk stratify patients with mild to moderate aortic dilatation rather than just moving the surgical cut point to somewhere below 5.5 cm. They had limited data in this regard, but showed that bicuspid valve — indexing the measures to body size — and the presence of severe systemic hypertension was not predictive.

There are several limitations to the Paratz study. There are no data on genetics, family history, smoking, medications, or comorbidities. Height was not measured in all of the patients. The echocardiograms were not over-read and there was no corroborating computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging data. Also, they accepted qualitative statements about aortic size if measurements were not available. In addition, they only captured fatal cases. Finally, some patients underwent surgery, and when these were considered deaths because presumably they would have died without surgery, the death rate in the severe dilatation group increased from 2% to 24%. Still, the majority of deaths would have occurred in the mild and moderate groups.