Constipation: Adult and Pediatric Considerations

August 1, 2024

Related Articles

-

Echocardiographic Estimation of Left Atrial Pressure in Atrial Fibrillation Patients

-

Philadelphia Jury Awards $6.8M After Hospital Fails to Find Stomach Perforation

-

Pennsylvania Court Affirms $8 Million Verdict for Failure To Repair Uterine Artery

-

Older Physicians May Need Attention to Ensure Patient Safety

-

Documentation Huddles Improve Quality and Safety

AUTHORS

Catherine A. Marco, MD, FACEP, Professor, Department of Emergency Medicine, Penn State Health, Hershey Medical Center, Hershey, PA

Matthew Turner, MD, Department of Emergency Medicine, Penn State College of Medicine, Hershey, PA

PEER REVIEWER

Steven M. Winograd, MD, FACEP, Attending Emergency Physician, Trinity, Samaritan Hospital, Troy, NY

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

- Constipation is a common condition across all age groups and demographics.

- The majority of constipation cases are benign, can be diagnosed solely through a thorough history and physical exam, and respond well to conservative management.

- Emergency providers should be aware of red-flag symptoms, such as change in stool caliber, bloody stools, and/or weight loss, which may indicate a new diagnosis of malignancy.

- The mainstay of conservative management of constipation includes lifestyle modifications, such as increasing activity level and dietary fiber.

- There are special considerations in the treatment of pregnant patients with constipation, such as avoidance of stimulant laxatives in the third trimester.

- It is important for the emergency clinician to consider emergent medical conditions that may present with constipation. Examples include patients who have small bowel obstruction, ileus, and fecal impaction.

- In pediatric patients, it is important to consider intestinal malformations and maintain a high degree of suspicion for acute abdominal emergencies that may be presenting with constipation.

- The majority of pediatric constipation causes are non-organic in nature and can be managed with conservative workup and treatment.

- Abdominal imaging (i.e., abdominal X-ray) is not required in the majority of pediatric patients presenting with uncomplicated constipation and should be avoided.

Constipation is a common diagnosis in the emergency department (ED) that has been steadily increasing in prevalence over the past several decades.1 As the morbidity and healthcare costs from this condition increase, it is important that ED physicians be aware of the workup, management, and potential complications of this common condition in adults and children alike.1

Demographics

Constipation is a common condition. Estimates range from 10% to 15% of the general population to up to 30% of the population will experience problems with constipation during their lifetime.2,3 More than $80 million is spent on over-the-counter laxatives in the United States every year.3 The prevalence of constipation increases with age; nearly 30% to 40% of individuals older than 65 years of age experience it.2 Other risk factors include polypharmacy as well as the female gender, with women experiencing chronic constipation at a rate approximately two to three times higher than that of men.2,3 Patients with lower socioeconomic status, lower rates of education, those experiencing stressful life events, those with a history of physical or sexual abuse, and those who report less physical activity also have higher rates of constipation.4

Differential Diagnoses

Constipation often has a complex and multifactorial pathogenesis, involving a wide range of factors, including diet, genetic predisposition, water intake, lifestyle, systemic diseases, behavioral disorders, medications, and a number of other factors.5 Table 1 provides a brief overview of the multiple differential diagnoses that ED physicians should be aware of in their initial workup of patients with constipation.

Table 1. Common Differential Diagnoses for Constipation5 |

|

Etiologies

Emergent Causes and Complications of Constipation

Before investigating any other etiologies, emergency medicine physicians should be aware of and vigilant for the handful of constipation presentations that require emergent assessment and intervention. Certain red flag symptoms include changes in bowel habits after age 50 years, blood mixed in with the stool, anemia, history of inflammatory bowel disease, weight loss, and family history of colon cancer.4,5

Bowel obstruction, either of the large or small bowel, can occur due to a number of etiologies, and often presents with nausea, vomiting, a distended bowel, and inability to pass flatus in addition to constipation.6 Patients with a history of prior abdominal surgeries, as well as history of bowel or gynecological cancer, have a particularly high risk of this complication.7 In the ED, these patients should be assessed with abdominal imaging with computed tomography (CT) scan.7 Intravenous (IV) fluids should be administered to replete any losses from vomiting, and certain cases of bowel obstruction will require a nasogastric tube placed to decompress the bowel.7 Concomitantly, the patient should be given analgesics, and the case should be discussed with surgery to determine if the patient requires operative intervention or a trial of non-operative therapy, such as bowel rest.6 Patients with small bowel obstruction require admission to the hospital.

Constipation due to acute spinal cord compression also should be recognized and managed emergently.6 This often may be seen in patients with advanced malignancies, where the incidence of metastatic spinal cord compression (MSCC) can be as high as 15%.6 In hospitalized patients, primary lung, prostate, and breast cancers are the leading causes of MSCC.8 Oncology patients who present with back pain, sensory deficits, and bowel or bladder dysfunction should be assessed with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the entire spine if possible. CT imaging should be used only if MRI is unavailable or contraindicated; X-ray imaging is not beneficial for determination of spinal cord compression in these patients.8 In cases of confirmed spinal cord compression, patients should be acutely managed with high-dose glucocorticoids both to provide analgesia and in an attempt to preserve neurological function, and should be emergently referred for surgical intervention.8 Patients with a known history of MSCC should be prophylactically managed with a mixture of a stimulant and osmotic laxatives, such as senna and polyethylene glycol (PEG), given their increased risk of constipation secondary to reduced mobility, nerve injury, and potentially concomitant opioid therapy.8

Constipation due to more benign etiologies still has a risk of severe complications.2 Chronic constipation may lead to fecal impaction, which has complications that range from urinary and fecal incontinence to stercoral ulcerations.2 In the most severe cases, bowel perforation can occur secondary to chronic constipation, due to the fecal mass causing ischemia and necrosis of the bowel wall.6 These patients are at high risk of rapid deterioration and will present with signs of peritonitis on physical exam.6 ED physicians should keep these life-threatening complications in mind when assessing patients with a history of chronic constipation.

Neurological Causes

Spinal Cord Injury. Gastrointestinal symptoms are common in patients with a history of spinal cord injury (SCI). Between 42% and 81% of SCI patients experience constipation; abdominal pain, distension, incontinence, diarrhea, hemorrhoids, rectal bleeding, and autonomic hyperreflexia also are common.9 As the lifespan of these patients increases because of improved care, it is becoming more likely that ED physicians will encounter this patient population in their practice.9

Because of the loss of sensory, motor, and reflex functions, SCI patients do not present with the typical clinical picture that would be expected of a patient with an acute abdomen. Instead of abdominal rigidity and absent bowel sounds, these patients may present with vague symptoms of dull pain, vomiting, restlessness, fever, and leukocytosis. Undiagnosed abdominal emergencies cause up to 10% of deaths in SCI patients.9 This is most dangerous in the acute phase of SCI, when patients may experience spinal shock with an elevated risk of acute abdominal pathology. SCI patients are at a higher risk of experiencing a paralytic ileus during these first several weeks and may require multiple enemas and manual disimpaction.9

Abdominal exams in SCI patients are limited in their accuracy. Abdominal pain may be dull and poorly localized, and irritation to the viscera may be referred to distant areas of the dermatome, with burning/hypersensitive areas of the skin present on exam. Approximately 32% of SCI patients will experience shoulder pain, due to irritation on the diaphragm being referred upward via the phrenic nerve.9 The abdominal walls may be spastic, making palpation difficult.9 Fecal impaction is common in these patients, and often presents only with loss of appetite and nausea.9 Because of the prevalence of chronic constipation, SCI patients are at a higher risk of colonic volvulus.9 Clinicians should have a lower threshold for imaging studies in these patients.

SCI patients with constipation respond well to lifestyle changes, such as increasing their fiber intake and bowel training, which is most effective if taken 30 minutes after breakfast because of the gastrocolic reflex.9 Other methods include digital stimulation of the anal canal, which can be done through a gloved finger in the rectum inducing sustained pressure toward the sacrum to relax the external anal sphincter and pelvic muscles. Rotating the finger will further relax the internal anal sphincter. Adjunctive therapies also can include abdominal massage, suppositories, oral laxatives, and enemas. The bisacodyl suppository and docusate oral agent are the most commonly used in this patient population, but other common methods, such as PEG suppositories and docusate, also may be used.9

In the most severe cases of chronic constipation, patients may have a Malone antegrade continence enema operation performed, where a small stoma is introduced through the appendix. Patients are able to introduce a catheter through the stoma to administer enemas that wash out the colon and rectum.9 Other surgical options include implanting a sacral nerve stimulator, colostomy, or ileostomy. In some circumstances, a patient’s primary physician may initiate additional medications, such as neostigmine and glycopyrrolate to aid in bowel function.9

Dyssynergic Defecation. Dyssynergic defecation (DD) is caused by an inability to coordinate the abdominal pulses and relaxation of the pelvic floor while straining.10 DD also is commonly referred to as pelvic floor dysfunction, functional outlet obstruction, and anorectal dyssynergia. DD typically is multifactorial in nature, resulting from a combination of the incoordination of muscles of defecation along with resistance to defecation. The resistance to defecation can be secondary to high anal resting pressure or paradoxical contraction of the pelvic floor and external anal sphincters, or reduced rectal propulsion forces, such as those caused by retained stool.11 DDs are caused primarily by a maladaptive pelvic floor contraction during the expulsive process, although reduced rectal sensation and structural deformities, such as rectoceles, also may be responsible.11 Regardless of the underlying cause, untreated DDs ultimately lead to chronically retained stool, which can lead to excessive straining, weakening of the pelvic floor, rectal intussusception, and ultimately neuropathy of the pudendal nerve, weakening the anal sphincters and leading to fecal incontinence.11

DD appears to be associated with maladaptive learning of sphincter contraction and/or incoordination of the abdominal, recto-anal, and pelvic floor muscles during childhood, perhaps due to ignoring the fecal urge, a desire to avoid pain, or trauma.11,12 Up to two-thirds of patients with DD appear to have developed it as an acquired behavioral disorder of defecation.12 A number of researchers have theorized that stressful life events, unconscious anger, and coercive toilet training during childhood may be responsible for DDs.13 However, other etiologies also may contribute. Women who sustained injuries during vaginal deliveries may have significant reductions in their anorectal squeeze pressures, predisposing them to DD.14 Older adult patients also have a higher risk of developing DD because of decreases in pelvic muscle strength, reductions in sphincter pressure, and changes in their rectal sensitivity.14

Patients may undergo outpatient evaluation for DD, including a balloon expulsion test or anorectal manometry to determine if the muscles of defecation are functioning properly. Formal anorectal manometry (ARM) testing may allow physicians to identify the specific process in defecation that is causing the patient’s symptoms.14 Unfortunately, DD often is non-responsive to conservative management and will require more aggressive treatment, such as biofeedback therapy.10

Slow Transit Constipation. Slow transit constipation (STC) simply refers to delayed stool transit through the colon. Most commonly seen in older adults, it often is due to age-related loss of enteric neurons and enteric glial cells, as well as an increase in inhibitory neurons in the colon.3 Patients also may have increased collagen deposition in their ascending colon as well as more binding sites for endorphins in their gut, further contributing to STC through a poorly understood process.3 Together, this appears to significantly reduce gut motility, particularly in elderly patients with chronic illnesses or nursing home residents.14 Mobility plays a significant role — in the least mobile nursing home residents, gut transit time can be prolonged up to three weeks, compared to the average length of three days in healthy patients.14 STC may be associated with disorders such as diabetes mellitus, hypothyroidism, hypercalcemia, or porphyria, or it may occur in the absence of any other disease process.3

Constipation Due to Peripheral Nerve Disease. Constipation also may occur due to disorders of the peripheral nervous system. Patients with a history of diabetic neuropathy may present with alternating diarrhea and constipation, caused by a combination of autonomic neuropathy, bacterial overgrowth, and dysmotility secondary to hyperglycemia.15 Similarly, patients with amyloid neuropathy also may present with alternating diarrhea and constipation due to uncoordinated contractions of the small bowel.15

Disorders such as Duchenne’s dystrophy may have an increased colonic transit time due to significant atrophy and fibrosis of the intestinal smooth muscles. In the most severe cases, this may present as a pseudo-obstruction, which is dilation of the colon without obvious transition point or clear obstruction (also known as Ogilvie’s syndrome).15 Patients with Ogilvie’s without signs of ischemia typically are managed nonoperatively with supportive care, neostigmine, and potential colonoscopic decompression.

Patients also may develop constipation secondary to pelvic nerve damage from childbirth or a prior surgery.15 Women with a history of vaginal childbirth have an increased risk of developing DD due to difficulties with sphincter contraction.14

Management of Constipation in Patients with Neurological Disease

In patients with constipation where a neurological disease is suspected, conservative therapy (which will be delineated later) should be initiated for cases of mild or intermittent constipation. However, if the patient has a history of severe and chronic constipation, they may require a more aggressive regimen with bulk laxatives and osmotics and have regular follow-up scheduled.15

Medications

Constipation may be caused by a wide range of medications, including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), anticholinergic agents such as tricyclic antidepressants and antipsychotics, calcium channel blockers, diuretics, iron supplements, calcium supplements, lithium, opioids, antihistamines, anticonvulsants, antacids, diuretics, and antirheumatic agents.10,14 Newer diabetic/weight loss agents, including tirzepatide and semaglutide, have been implicated in slower gastrointestinal transit and constipation.16

Chemotherapy-induced constipation (CIC) is reported by approximately 50% to 87% of patients undergoing cytotoxic chemotherapy.17 Fortunately, there are minimal interactions between most constipation medications and cancer-directed therapy.17 Lactulose, in particular, appears to be effective for patients with refractory vincristine-induced constipation.17

Opioid-Induced Constipation. Narcotics are a frequent cause of constipation.18 Up to 94% of patients taking opioids for cancer-related pain, and 41% of patients with chronic non-cancer pain, will experience opioid-induced constipation (OIC).19 Opiates have both peripheral and central effects on intestinal motility, inhibiting intestinal secretions, increasing fluid and electrolyte absorption from the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, delaying GI transit, and stimulating the pylorus and ileocecal sphincters.18,20 Transdermal fentanyl has the lowest risk of OIC, while oxycodone CR and morphine CR have the highest risk.18

As with most causes of constipation, conservative therapy with increased fiber, activity levels, and fluid consumption should be initiated first. However, patients with OIC likely will require stool softeners and laxatives, since the primary mechanism driving their constipation is decreased transit time.18 Patients also may benefit from rotating through various opioids. Because of incomplete cross tolerance, patients may require a lower dose of an opioid that they are naïve to, reducing the potential risk of adverse effects such as OIC.18

Various medications, such as mu-opioid receptor antagonists including naloxone and naltrexone, may reverse the GI effects of opioids. Unfortunately, these medications also will reverse the central nervous system (CNS) effects of opioids, possibly leading to withdrawal or the cessation of analgesia.20 Because of its systemic spread throughout the body, naloxone has an extremely narrow therapeutic index to increase GI motility before it can potentially reverse analgesia. However, growing research shows that it may be used safely to reverse OIC if given in combination with extended-release oxycodone.20 Peripherally acting mu-opioid receptor antagonists, such as methylnaltrexone and alvimopan, appear to be somewhat effective in reducing OIC without increasing the risk of withdrawal or loss of analgesia.20 Prucalopride, a 5-HT4 agonist that acts as a colonic prokinetic agent, also appears to significantly improve patient-reported severity of constipation in OIC patients.20

When prescribing opioids in the ED, physicians should be aware of the risk of potential OIC. In cases where the patient will require long-term opioid coverage, the patient should initiate a bowel regimen prior to starting narcotics.18

Mechanical Causes of Constipation

A number of mechanical etiologies may lead to constipation, including prior exposure to radiation, intussusception, internal rectal prolapse, mucosal prolapse, rectocele, enterocele, malignancy, and anal stenosis.21

Fecal impaction (FI), defined as a large mass of stool in the rectum or colon that is unable to be evacuated, may worsen constipation.22 FI is a common complaint in older adults and becomes more prevalent with increasing age.22 This condition is tied with significant mortality and morbidity. A 2020 study of 32 patients presenting to an ED with FI found that 40.6% experienced significant FI-related morbidities; 21.9% died during their subsequent hospital stay.22 Potential complications include obstruction of urinary outflow, colon perforation, dehydration, incontinence, ulcers, and rectal bleeding.23 Older adult patients with FI should be quickly treated with digital disimpaction, enemas, and laxatives, and closely monitored for further complications.22 Patients with FI should not be given stimulant laxatives.15

Patients with a history of primary or secondary megarectum often will experience constipation secondary to fecal impaction, due to a decreased inability to experience the sensation of rectal fullness.21 Hirschsprung’s disease (HD), which is primarily defined by agangliosis of the rectum, has a similar mechanism. When the rectum is distended, there is no relaxation of the internal anal sphincter, leading to further distension and functional obstruction.21 Chagas disease also may lead to this.3

Patients also may experience mechanical constipation secondary to descending perineum syndrome (DPS).21 Often seen in patients with a history of injury to the sacral nerves from trauma, childbirth, or chronic straining, DPS occurs because of ballooning of the perineum below the bony outlet of the pelvis during straining, leading to obstructed defecation as the anterior rectal wall protrudes into the anal canal.21,24 Because of a continuous sensation of rectal fullness, patients will need to strain more and more, leading to worsening denervation of the external anal sphincter and puborectalis muscles, and ultimately to fecal incontinence.21

Patients may experience strictures secondary to prior bowel ischemia and/or prior recurrent episodes of diverticulitis, leading to mechanical obstruction.11 Anal fissures also may be responsible for mechanical obstruction causing constipation, simply due to the discomfort that the patient may experience.11 These should be investigated via digital rectal exam (DRE).11 Anal fissures have a high rate of recurrence; patients with a history of fissures should be started on a high-fiber diet to improve healing and reduce recurrence rates.25 The most extreme cases may require surgical intervention.25 The diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease should be considered in patients with recurrent fissures and/or in patients without clear etiologies for anal fissures.

Other Causes of Constipation

A number of metabolic disorders may contribute to constipation, including hypercalcemia, hypocalcemia, hypothyroidism, hypomagnesemia, uremia, and heavy metal poisoning.11,21 Disorders such as systemic sclerosis and amyloidosis also increase the risk of constipation.11,21

Constipation has long been considered a side effect of depression, whether as a physical symptom or due to iatrogenic effects from antidepressant medications.26 However, a recent 2024 article has proposed that diagnosed and self-reported constipation is associated with an elevated risk of depression, suggesting that it may be an independent risk factor in influencing patients’ mental health.26 While further research is required in this field, physicians should assess patients with constipation for any symptoms consistent with depression or undiagnosed mental illness.26

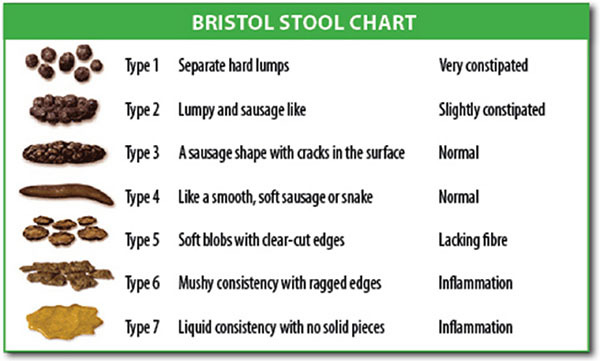

History

The initial assessment of the patient should be detailed and thorough. ED physicians should determine the consistency, frequency, and size of stools; the duration of the constipation; history of ignoring the fecal urge; sensation of incomplete evacuation of the bowels; and any maneuvers the patient performs to aid in defecation, such as palpation with the hand or excessive straining at the beginning/end of defecation.4,5 Tools such as the Bristol Stool Form Scale (see Figure 1) and bowel habit diaries can be extremely helpful in the initial diagnostic stage, especially as self-reported stool habits without the aid of a journal often are inaccurate.4 Patients complaining of perceived constipation may be under the impression that they require at least one bowel movement a day. However, in the United States, the normal range is between three and 21 bowel movements per week.4 Patients also may have symptoms of abdominal distention, discomfort, and bloating.4 For patients with chronic constipation, tools such as the Patient Assessment of Constipation Quality of Life (PAC-QOL) offer a brief and comprehensive assessment on the overall well-being of patients secondary to their constipation.27

Figure 1. Bristol Stool Chart |

|

Source: Cabot Health, Bristol Stool Chart, CC BY-SA 3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0, via Wikimedia Commons |

ED physicians may find tools such as the Rome IV criteria helpful. Released in 2016 with a focus on multicultural patients, the Rome IV diagnostic criteria assess for a wide range of functional GI disorders without limiting their focus to a purely Western-centered bias, making them effective for a wider range of patients.19 Table 2 demonstrates the definition of functional constipation per the Rome IV criteria. The Rome IV criteria also have diagnostic criteria for OIC and further subtypes for irritable bowel syndrome with constipation, functional constipation, and functional defecation disorders.28,29

Table 2. Functional Constipation per the Rome IV Criteria28 |

Must include two or more of the following:

|

Patients should provide a full medical history, including medications, recent weight loss, family history of colonic cancer, any sudden changes in bowel habits, anemia, timing in symptom onset, caloric and fiber intake, any history of opioid or laxative abuse, any history of obstetric events, rectal pain, fever, and vomiting.4,30 Any sudden changes in stool caliber should be regarded as an alarm symptom and warrant a possible referral for colonoscopy.18 As noted later, the patient should be assessed for any history or evidence of neurological, endocrine, or metabolic disorders.30 The patient’s psychosocial history also should be assessed, particularly regarding stress management techniques, depression, and anxiety.30 In many cases, a well-documented clinical history may be sufficient to identify the etiology of the constipation without the need for further testing.5

Physical Exam

The patient’s physical exam should not be focused on the abdomen alone, but the physician should perform a complete examination for any evidence of systemic disease. The patient’s weight, nutritional status, pallor, neurological status, and reflexes should be assessed for evidence of hypothyroidism and other metabolic abnormalities.30 The patient’s abdomen should be examined for masses, distension, tenderness, altered bowel sounds, and peritoneal signs.6,30 A chaperoned perineal and rectal examination also should be performed. To test the anal resting tone, the examiner should insert a finger into the anus. The patient then should attempt to expel the finger by mimicking defecation; this will allow the provider to test for impaired relaxation or even paradoxical contraction of the anal sphincter.4 The rectal exam also should assess for impacted stool, rectocele, or puborectalis tenderness.4 Potential causes of anal pain, such as fissures, hemorrhoids, and rectoceles, also should be assessed.5 In cases of suspected neuropathy, the provider may use a cotton swab to gently stroke the four quadrants of the perineal skin and observe for reflex contraction of the external anal sphincter. If there is no reflex, neuropathy may be present.14 Patients also should bear down as if to defecate; any failure to relax the external anal sphincter or failure of perineal descent, typically 1 cm to 3.5 cm, increases the likelihood of DD.14,18

Diagnostic Testing

Laboratory Studies

Although a thorough history and physical exam are sufficient for diagnosis in many cases of constipation, basic laboratory studies may be ordered, including electrolyte panel, glucose and calcium levels, thyroid function tests, urine tests, and a complete blood count (CBC).5 In most cases of uncomplicated constipation, the diagnostic utility of these tests is low.4 As discussed later in the Pediatric section of this article, laboratory tests should only be ordered when physicians suspect an underlying organic cause, ranging from cystic fibrosis to metabolic/electrolyte derangements.31

Imaging

In general, abdominal imaging should be ordered only in patients with alarming symptoms, significant worsening of symptoms, when there is diagnostic uncertainty, or in abnormal physical examinations.32 Abdominal radiography does not appear to significantly affect the ED management of patients with constipation, and it appears to have a low utility other than confirming increased fecal load.33 A 2020 study of 481 ED patients who presented with constipation and had an abdominal X-ray done found that only a small number of patients had any concerning diagnoses, such as bowel perforation, identified on this imaging — concerning diagnoses that would have been identified without imaging with an adequate history and physical exam.33

Pediatric patients in particular should have imaging done only sparingly, for highly specific circumstances in which a rectal exam cannot be performed due to a history of trauma, or if the diagnosis remains uncertain after a history and physical exam.31 The Children’s Oncology Group recommends that abdominal radiography and CT scans be minimized in pediatric oncologic patients because of the risks of secondary neoplasms.23 Despite this, a 2022 study found that up to 66% of children presenting with constipation at the ED have abdominal radiographs done.1 If a patient presents with atypical features, has significant abdominal tenderness, is an unreliable historian (e.g., older adult patients/dementia/prior traumatic brain injury patients), or the provider has diagnostic uncertainty with concerns for bowel obstruction, either due to malignancy or another etiology, imaging such as abdominal radiography or CT scan should be considered.34

Other Diagnostic Tests

Typical gut transit time will take about three days for healthy patients. To assess colonic transit time, primary care physicians or gastroenterologists may order a colonic transit study, where patients swallow radiopaque markers and have a follow-up abdominal radiograph performed six days later, allowing for the assessment of disorders such as STC.13,34

In cases of abdominal bloating and distension secondary to constipation or difficult evacuation, patients should have outpatient anorectal physiology testing done to rule out any evidence of pelvic floor disorders.32 ARM testing can be used to assess pressure levels in the rectum and anal sphincters and determine if the patient is able to adequately coordinate the complex anorectal processes that lead to defecation.13 Patients with a suspected diagnosis of DD should have a referral for an ARM test to assess for impaired rectal contraction, impaired relaxation, or paradoxical anal contraction during defecation.13

The balloon expulsion test is a another diagnostic test that can aid in the diagnosis of DD. Although uncommonly performed in the ED, it is a simple test that may lead a physician to the diagnosis of DD. In this test, a 4 cm balloon filled with 50 mL of warm water is inserted into the patient’s rectum, and the patient then attempts to expel the balloon. If the patient cannot expel the balloon within one minute, they are likely experiencing some form of DD.13 Defecography is a similar test, where 150 mL of barium are placed in the rectum to simulate stool. CT scans allow physicians to measure the patient’s anorectal angle at rest and during defecation maneuvers. Typically, defecography is an excellent test for diagnosing abnormalities such as descending perineum syndrome.25

Management of Constipation

Conservative Management

The majority of constipation cases can be managed conservatively. Lifestyle changes should be initiated first. Sedentary patients are three times more likely to develop constipation.13 Even minor increases in exercise, such as starting a 20-minute walk each day, have been shown to have a clinically significant impact.9 Patients may supplement their diets with increased soluble fiber, which increases stool bulk and stimulates peristalsis. To avoid complications, patients should start by adding 3 g to 4 g of soluble fibers, such as psyllium and ispaghula husk, to their diet each day, gradually increasing this to a dosage of 20 g to 30 g per day in total, to minimize the risks of abdominal discomfort or bloating.9 Dried plums also may effectively manage mild to moderate constipation.13 While some sources recommend patients with constipation increase their fluid intake, this generally does not appear to be effective for the treatment of constipation except for patients with dehydration.4,9 Evidence suggests that probiotics may be effective in treating constipation.35,36

While increasing fluid and fiber intake is benign in most patients, there are a number of exceptions to increasing fluid and fiber intake. Patients with conditions such as STC and DD do not respond well to increased dietary fiber, and increased fluid intake should be done carefully in patients with a history of cardiac or renal disease.13

To take advantage of the gastrocolic reflex, constipated patients should attempt to regulate their bowels by establishing timed toilet training, typically by attempting a bowel movement twice a day, 30 minutes after a meal, and to strain for no more than five minutes.13

In DD-related cases of constipation, patients may benefit from biofeedback therapy to improve coordination of their abdominal and anorectal muscles.12

Medications. Osmotic laxatives, such as lactulose, PEG, and magnesium, function by pulling fluid into the colonic lumen and facilitating defecation.12 (See Table 3.) These doses can be titrated to increase stool softness and ease of transition through the GI tract.4 PEG generally is well tolerated and more effective than lactulose for improving stool frequency, consistency, and abdominal pain. Supplementation with mineral water rich in magnesium hydroxide salts also has been shown to be effective in improving stool frequency and consistency in patients without renal disease.4

Table 3. Common Medications for Treatment of Adult Constipation4 |

|

Treatment |

Dose/Comments |

Fiber Intake |

|

Soluble fiber |

Psyllium/ispaghula husk, add 3 grams to 4 grams per day, gradually increase to 20 grams to |

Osmotic Laxatives |

|

Lactulose |

20 grams daily4 |

Polyethylene glycol (PEG) |

17 grams daily4 |

Magnesium hydroxide salts |

Milk of magnesia once or twice daily4 |

Stimulant Laxatives |

Defer if suspected obstruction or fecal impaction22 |

Senna |

|

Bisacodyl |

10 mg daily, suppository form 30 minutes after breakfast4 |

Glycerin |

Suppository form 30 minutes after breakfast4 |

Secretagogues |

Defer unless patient has failed more conservative treatment18 |

Lubiprostone |

|

Linaclotide |

72 mcg or 145 mcg daily4 |

Plecanatide |

3 mg or 6 mg daily4 |

Stimulant laxatives are less well tolerated than osmotic laxatives, with higher rates of abdominal cramping and pain, but also may be used to treat constipation.12 They also may be used as rescue therapy for patients with no bowel movements while on another class of laxatives for three days.12 Stimulant laxatives induce prolonged colonic contractions. Senna, bisacodyl, and sodium picosulfate are extremely safe and may be used as rescue agents for acute relief of constipation or for longer-term, more regular therapy.4 For maximum effectiveness, bisacodyl and glycerin should be given via suppository form approximately 30 minutes after breakfast to synchronize with the body’s gastrocolic reflex.4 Stimulant laxatives are contraindicated in patients with concern for obstruction or fecal impaction.22

Secretagogues, such as lubiprostone, linaclotide, and plecanatide, increase intestinal chloride secretion, leading to increased water secretion in the intestines, accelerating transit time throughout the GI tract.4 These medications generally should be deferred unless the patient already has failed more conservative treatment.17 While lubiprostone is safe for use in healthy individuals, it should not be used by pregnant women; women of childbearing age using this medication also should use contraceptives.4

Other medications include serotonin 5-hydroxytryptamine receptor agonists, such as prucalopride, a medication recently approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), that may treat idiopathic chronic constipation.4 Prucalopride has no cardiovascular side effects and significantly improves constipation-related quality of life measures.12 Low-dose colchicine taken at 1 mg daily also may be an effective treatment for constipation caused by STC, due to the unknown mechanism by which this drug induces diarrhea.13 Prokinetic agents such as metoclopramide also may be effective in patients who do not have suspicion for physical obstruction.34

Disimpaction and Enemas. In the ED, patients with fecal impaction may require manual disimpaction, performed via digital fragmentation and extraction of the stool.25,27 Lubricating enemas and suppositories may be helpful in these cases. In the most severe cases, the patient may require surgical removal of the impaction.27

Enemas function by distending the rectum, stimulating the colon to contract and eliminate stool. Some, such as soap suds enema, use a hypertonic solution to provide a detergent-based mucosal irritation to stimulate defecation.37 Others, such as the Fleet enema, use phosphate to directly stimulate the muscles of the colon.38 However, the Fleet enema has a risk of hyperphosphatemia in patients with chronic renal failure or in patients taking angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors.38 Even cleansing enemas without phosphate, such as the Easy Go enema, have a risk of perforation secondary to the device tip, localized weakness of the rectal wall, or obstruction.38 Enemas should be done by experienced personnel, and are contraindicated in patients who are immunocompromised or undergoing chemotherapy.38

Surgical Management

In the most extreme cases, patients may require surgery for removal of fecal impaction, colectomy, cecostomy, or other aggressive procedures.27 However, given the high rate of potential complications such as incontinence, bowel obstruction, small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO), or small intestinal fungal overgrowth (SIFO), these procedures should be done only as a last resort.12,13 In severe cases of STC, subtotal colectomy with ileorectal anastomosis appears to be an effective treatment.13 However, in patients with DD, subtotal colectomy typically is not as effective unless the patient already has shown improvement with biofeedback therapy.13

Sacral nerve stimulation also may be effective in patients, although this procedure has a failure rate of up to 20%.39 Another form of treatment is the antegrade continence enema (ACE), where a colonic conduit through a stoma in the patient’s abdomen is made, allowing patients to perform controlled irrigation of their colon with up to 2 liters of water or saline per day.39 The ACE procedure may be effective in both adult and pediatric patients with either severe fecal incontinence or a history of severe constipation.39

Special Populations

Pregnancy Considerations

Pregnancy is associated with many GI complaints, ranging from nausea and vomiting to significant heartburn.40 Constipation affects 11% to 38% of all pregnancies. Pregnant women may develop constipation for the first time, or may experience an acute worsening of previous symptoms.41 Increased progesterone levels, particularly in the first and second trimesters of pregnancy, lead to reduced intestinal smooth muscle motility. This, in combination with increased water absorption and increased secretion of the inhibitory hormone relaxin, causes increased stool transit time and hardened stools.41 In addition, the growing uterus causes a mechanical impedance with compression of the bowels, which could further exacerbate constipation.42 Pregnant women also appear to consume less fiber and fluids during the third trimester, which may further contribute to constipation.43

Fortunately, most pregnant women respond well to conservative therapy. Simply increasing fiber intake should be used as a first-line therapy for pregnant patients.44 Bulk-forming laxatives, such as wheat bran, ispaghula husk, methylcellulose, and sterculia, may improve symptoms and have no impact on fetal health.41 Osmotic laxatives, such as lactulose and PEG, also are safe in pregnancy; PEG is the treatment of choice in chronic constipation in pregnancy.41 Glycerin suppositories may be used safely in pregnancy as well.41 However, there is no evidence regarding the safety of phosphate enemas in pregnancy — these should be avoided.41

Stimulant laxatives, such as bisacodyl and senna, should be used cautiously during the third trimester, since they have been found to stimulate uterine contractions.41 Likewise, docusate also should be used only if the patient has failed other treatment options, since it has been known to cause neonatal hypomagnesemia and also is excreted in breast milk.41 Newer agents, such as prucalopride, lubiprostone, and linaclotide, have had limited studies on their safety profile in pregnancy and generally should be avoided if possible.41

Pediatric Considerations

Constipation is a common problem in pediatric medicine; an estimated 29.6% of children worldwide will experience functional constipation.45 Unfortunately, the clinical presentation of constipation may be challenging in pediatric patients because of reduced communication, making diagnosis less straightforward for the clinician.46 As a general rule, a neonate will average three to four stools per day for the first week of life, infants and toddlers will average two stools per day, and preschoolers will average one stool per day.31 However, frequent exceptions exist; for example, it is common for breastfed infants to go several days to up to two weeks without a bowel movement.31

Infant Constipation

Of all pediatric patients, neonates are the most likely to have organic causes of their constipation.47 Physicians may find the Brussels Infants and Toddlers Stool Scale a useful assessment to describe stool consistency in this population.48 Diseases such as HD — due to a congenital aganglionic megacolon — occur in one in 5,000 births. Failure to pass meconium within 48 hours of birth should raise suspicion for HD in neonates; however, it is important to note that 50% of infants with HD still will pass meconium within the first 48 hours.47,49 Affected infants also may display abdominal distension, failure to thrive, and “pencil-thin” or “ribbon-like” stools.47,50 They also may display explosive stools after withdrawal of the examining finger.49 Any infants with these symptoms and evidence of empty rectum on physical exam should be evaluated for HD. Undiagnosed cases of HD may advance to enterocolitis, with fever, bloody diarrhea, and abdominal distension in the second and third months after birth.47

Infants also are significantly more likely to develop constipation secondary to congenital defects, such as from anorectal malformations, and spinal cord malformations such as spinal bifida, tethered cord, and myelomeningocele.47 Infants also may develop constipation secondary to hypothyroidism, with associated symptoms of bradycardia, enlarged fontaneles, and poor growth.47 Cystic fibrosis also may cause infant constipation and can present with associated pneumonia, respiratory failure, poor growth, fever, failure to thrive, and rash.47 Other potential causes of neonatal constipation include multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2B (MEN 2B), diabetes insipidus, hypercalcemia, celiac disease, and a number of other causes.50

Despite these potential etiologies, more than 90% of infants with constipation have no organic causes found. Constipation is more common in formula-fed infants, suggesting that diet plays a significant role.51 Furthermore, patients often may be misdiagnosed with constipation when they actually experience “infant dyschezia” as a result of infants learning to coordinate intraabdominal pressure with relaxation of the pelvic floor muscles. Patients with infant dyschezia may scream, strain, and turn red as they attempt to defecate for up to 10-20 minutes. This condition is self-limiting and drops from an incidence of 3.9% at 1 month of age to 0.9% at 9 months of age.50

For true cases of constipation, infants initially should have dietary changes made, and then be reassessed.47 Cow’s milk protein allergy may lead to constipation; infants with suspicion for this should undergo a two- to four-week trial avoiding cow’s milk.50 Sorbitol-containing juices, such as prune, pear, and apple juice, may help; however, physicians should be aware of the high degree of fructose intolerance in this population.50 Lactulose dosed at 3 mL/day to 5 mL/day, or a small amount of PEG, also may be given.50 Infants may be treated safely with glycerin suppositories for acute impaction.47

Pediatric Constipation

If a child presents with abdominal pain, it is important that the provider rule out emergent etiologies such as appendicitis through a thorough medical, surgical, dietary, and medication history.46 The Rome IV diagnostic criteria provide a useful framework for the clinical diagnosis of constipation in this population.46

Approximately 95% of pediatric patients presenting with constipation have functional constipation (FC).45 Constipation is defined as FC if there is no underlying organic cause, and it typically is the result of chronic withholding behaviors. Pediatric patients with chronic constipation will present with painful and infrequent defecation, abdominal pain, and even fecal incontinence.52,53 FC may be difficult to manage and can negatively affect the quality of life for patients and family members alike.53

Pediatric patients should have a thorough medical history taken that focuses on age of onset, passage of first meconium, typical frequency and consistency of stools, incontinence, withholding behavior, diet, changes in weight, and nausea/vomiting.52 Past success or failure with toilet training, stressful life events, family history of GI issues, and any history of neurodevelopmental delay also should be investigated.49,52 If possible, a three-day food diary should be obtained to better assess fluid and food intake.49 Any family history of GI diseases, such as HD, food allergies, inflammatory bowel diseases, and other abnormalities of the thyroid, parathyroid, or kidneys, or systemic diseases such as cystic fibrosis, also should be obtained.49 While the Bristol Stool Scale may be used in toilet-trained children, the Amsterdam Stool Scale may be used for infants.52 In the physical exam, the child’s growth should be assessed in addition to assessment of the lumbosacral, perianal, and abdominal regions.52 Interestingly, children with constipation often appear to have a differing demeanor than children with other chronic GI complaints, often appearing more withdrawn, angry, and embarrassed about their symptoms. Pediatric patients often may deny their constipation during interview.54 The physical exam should include evaluation of growth parameters, examination of the perineum and perianal area, evaluation of the thyroid and spine, testing for the cremasteric, anal wink, and patellar reflexes, as well as digital exam of the anorectum for perianal sensation, rectum size, tone, and anal wink.31

While the vast majority of pediatric patients present with a non-organic cause of constipation, physicians should pay particular attention to a number of warning signs in the history and physical exam. Infants younger than 1 month of age presenting with constipation have a greater likelihood of an organic etiology.31 Meconium delayed more than 48 hours after birth is highly suggestive of HD, although this is not specific. Fifty percent of children with HD will pass meconium within 48 hours.31,49 Any systemic symptoms, including decreased appetite, weight loss, fever, and vomiting, also are more suggestive of organic etiology.31 The physical exam also may show evidence of spinal cord abnormalities, abdominal distension, and a number of other findings in organic pediatric constipation.31 Table 4 provides a list of concerning red flags that may suggest an organic cause of constipation.

Table 4. Red Flags for Organic Etiology in Pediatric Constipation31 |

|

History/Physical Exam Finding |

Possible Diagnosis |

Meconium > 48 hours after birth |

HD, cystic fibrosis, congenital malformation of anorectum, spinal malformation |

Constipation before 1 month of age |

Congenital malformation of anorectum, spinal malformation, allergies, metabolic/endocrine disorder, HD |

Failure to thrive |

Metabolic disorder, malabsorption, cystic fibrosis, HD |

Abdominal distension ± vomiting |

Pseudo-obstruction, fecal impaction, HD, pyloric stenosis |

Intermittent diarrhea and explosive stool, empty rectum, tight anal sphincter, gushing of stool with physical exam |

HD |

Pilonidal dimple w/tuft of hair, midline pigmentary abnormalities of lower spine, abnormal neurologic exam — absent anal wink, absent cremasteric reflex, decreased LE tone/reflexes |

Spinal cord abnormality |

Blood in stool |

HD, allergy |

Extreme fear during anal inspection and/or anal fissures, history of smearing feces |

Sexual abuse49 |

Systemic symptoms: fever, vomiting, toxic appearance |

HD, neurenteric problem |

No response to conventional treatment |

HD, neurenteric problem, spinal cord abnormality |

HD: Hirschprung’s disease; LE: lower extremity |

|

Both the European Society of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition (ESPGHAN) and the North American Society of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (NASPGHAN) do not recommend abdominal radiography, given the risk of radiation exposure, the chance of misdiagnosis, and the lack of diagnostic association between clinical symptoms of constipation and fecal load on abdominal imaging.52 Imaging should be employed sparingly, in patients where a DRE cannot be performed due to severe anxiety or history of abuse, or in extremely obese patients who cannot have a proper abdominal exam performed.52 Likewise, if the patient has no concerning symptoms, typical laboratory studies for testing of hypothyroidism, celiac disease, vitamin D status, hypercalcemia, and milk allergy are not recommended.52 Barium enemas may be indicated for suspicions of anatomic malformations, while spinal MRI may be indicated for suspicion of spinal cord abnormalities.31 A number of laboratory tests may be indicated in pediatric constipation, as shown in Table 5.

Table 5. Laboratory Studies to Evaluate Pediatric Constipation31 |

|

Suspected Diagnosis |

Laboratory Tests |

Lead toxicity |

Lead toxicity |

Celiac disease |

Tissue transglutaminase immunoglobulin (Ig)A, total IgA |

Cystic fibrosis |

Sweat test |

Drug use/toxins: opiates, anticholinergics, antidepressants, antihypertensives, etc. |

Drug level |

Hypothyroidism, hypercalcemia, hyperkalemia |

Thyroid studies, serum calcium and potassium levels |

Diabetes mellitus, diabetes insipidus |

Fasting serum glucose, serum and urine osmolarity |

FC initially should be managed with similar conservative management as noted earlier. The majority of pediatricians recommend initially increasing dietary fiber and fluid intake. Up to 90% of American children do not have enough fiber in their diet; possible treatments include psyllium, cellulose, cocoa husk, and a number of other supplements. However, data on the specific efficacy of fiber supplements for pediatric patients are limited.55 Cow’s milk allergy (CMA) is a common cause of constipation in pediatric patients. In cases where CMA is suspected, patients may respond well to several weeks of an elimination diet.55 While the data for probiotics are contradictory, early research for the use of prebiotics and synbiotic supplements in pediatric constipation are promising.55

If a bowel regimen is required, it may be done orally through an osmotic laxative, such as PEG treatment at 1 g/kg to 1.5 g/kg for three to six days or through an enema. (See Table 6.) However, enemas may be difficult to perform in pediatric patients due to anxiety.52

Table 6. Bowel Regimen Therapies for Pediatric Patients 31 |

|

Therapy |

Dose |

Polyethylene glycol (PEG) (osmotic) |

1 g/kg to 1.5 g/kg per day31,52 |

Magnesium citrate (osmotic) |

2 mL/kg/day to 4 mL/kg/day for < 6 years 100 mL/day to 150 mL/day for 6-12 years 150 mL/day to 300 mL/day for > 12 years |

Senna (stimulant) |

2.5 mL/day to 7.5 mL/day for 2-6 years 5 mL/day to 15 mL/day for 6-12 years |

Bisacodyl (stimulant) |

5 mL/day to 15 mL/day for > 2 years |

Saline (rectal enema) |

5 mL/kg to 10 mL/kg; once per day |

Mineral oil (rectal enema) |

15 mL to 30 mL per year of age, up to 240 mL; once per day |

Soap suds (rectal enema) |

20 mL/kg of tap water and one packet of Castile soap37 |

For treatment of chronic constipation, patients may need to be taking laxatives for several months and should be referred to a gastroenterology specialist if their constipation does not improve.52 In pediatric patients, PEG appears to the optimal laxative in most cases, with multiple studies finding it superior to lactulose, placebo, milk of magnesia, mineral oil, and dietary fibers.52 Table 7 provides a brief overview of a number of maintenance therapies.

Table 7. Maintenance Therapies for Pediatric Constipation31 |

|

Therapy |

Dose |

Polyethylene glycol (PEG) (osmotic): first-line therapy |

0.5 g/kg to 0.8 g/kg up to 17 g daily |

Lactulose (osmotic): first-line therapy |

1 mL/kg, either once per day or in two divided doses |

Magnesium hydroxide (osmotic) |

0.5 mL/kg/day for age < 2 years 5 mL/day to 15 mL/day for age 2-5 years 15 mL/day to 30 mL/day for age 6-11 years 30 mL/day to 60 mL/day for > 12 years |

Senna (stimulant) |

1.25 mL to 2.5 mL at bedtime for 1 month to 2 years of age 2.5 mL to 3.75 mL at bedtime for 2-6 years of age 5 mL to 7.5 mL at bedtime for 6-12 years of age 10 mL to 15 mL at bedtime for > 12 years of age |

Bisacodyl (stimulant) |

5 mg to 15 mg daily for > 2 years of age |

Mineral oil (lubricant) |

5 mL/day to 15 mL/day for children 15 mL/day to 45 mL/day for adolescents |

Treatment is most effective when behavioral therapy is paired with laxatives and other conservative management.52 Cognitive behavioral therapy, often in the form of play therapy to reduce child stress and anxiety around defecation, is both safe and effective for bowel training.55 Providing families with a Constipation Action Plan (CAP) for the treatment of FC may be effective, giving patients a clearly understandable way to recognize symptoms and adjust lifestyle interventions. A number of tertiary pediatric centers have designed CAPs for children with FC, but the 2021 Uniformed Services Constipation Actional Plan (USCAP) designed at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center appears to be particularly effective because of its liberal use of easily comprehensible pictographs.53

A minority of FC is not due to withholding behavior, but to slow transit through the gut, similar to STC.52 These patients also should be initiated on conservative management.

Unfortunately, pediatric constipation is difficult to treat. Up to 40% of constipated children will remain symptomatic after two months of treatment, many of whom will have symptoms that persist into adolescence and adulthood.52,55 Parents should be made aware that this often is a lengthy and difficult treatment course that will require patience and understanding in combination with conservative management and further behavioral modification.52

Conclusion

Constipation is a frequently encountered condition in the ED. The emergency clinician should perform a thorough history and physical exam to evaluate for other diagnoses that may be presenting with constipation. In addition, a thorough evaluation may elucidate the etiology of the patient’s constipation and can guide the diagnostic workup and management options. Imaging typically is not required in most patients presenting with uncomplicated constipation. Special populations, such as patients who are pregnant and pediatric patients, require an understanding of the various factors involved in constipation because management options may differ in these populations.

REFERENCES

- Zhou AZ, Lorenz D, Simon NJ, Florin TA. Emergency department diagnosis and management of constipation in the United States, 2006–2017. Am J Emerg Med 2022;54:91-96.

- Dennison C, Prasad M, Lloyd A, et al. The health-related quality of life and economic burden of constipation. Pharmacoeconomics 2005;23:461-476.

- De Giorgio R, Ruggeri E, Stanghellini V, et al. Chronic constipation in the elderly: A primer for the gastroenterologist. BMC Gastroenterol 2015;15:1-3.

- Bharucha AE, Wald A. Chronic constipation. Mayo Clin Proc 2019;94:2340-2357.

- Forootan M, Bagheri N, Darvishi M. Chronic constipation: A review of literature. Medicine 2018;97:e10631.

- Gonzalez CE, Halm JK. Constipation in cancer patients. Oncologic Emergency Medicine: Principles and Practice. Springer International Publishing;2016:327-332.

- Ripamonti CI, Easson AM, Gerdes H. Management of malignant bowel obstruction. Eur J Cancer 2008;44:1105-1115.

- Lawton AJ, Lee KA, Cheville AL, et al. Assessment and management of patients with metastatic spinal cord compression: A multidisciplinary review. J Clin Oncol 2019;37:61-71.

- Ebert E. Gastrointestinal involvement in spinal cord injury: A clinical perspective. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis 2012;21:75-82.

- Krogh K, Chiarioni G, Whitehead W. Management of chronic constipation in adults. United European Gastroenterol J 2017;5:465-472.

- Bharucha AE, Lacy BE. Mechanisms, evaluation, and management of chronic constipation. Gastroenterology 2020;158:1232-1249.

- Sharma A, Rao S. Constipation: Pathophysiology and current therapeutic approaches. Handb Exp Pharmacol 2017;239:59-74.

- Siproudhis L, Lehur PA. Defecation disorders. In: Herold A, Lehur PA, Matzel KE, O’Connell PR. Coloproctology. Springer;2017:121-133.

- Rao SS, Go JT. Update on the management of constipation in the elderly: New treatment options. Clin Interv Aging 2010;5:163-171.

- Winge K, Rasmussen D, Werdelin LM. Constipation in neurological diseases. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2003;74:13.

- Twarog C. Comparison of the intestinal permeation enhancers, SNAC and C, for oral peptides: Biophysical, in vitro and ex vivo studies. Medication. Universite Paris-Saclay; University College of Dublin; 2020.

- Belsky J, Stanek J, Yeager N, Runco D. Constipation and GI diagnoses in children with solid tumours: Prevalence and management. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2023;13:e1166-e1173.

- Toney RC, Wallace D, Sekhon S, Agrawal RM. Medication induced constipation and diarrhea. Pract Gastroenterol 2008;32:12.

- Schmulson MJ, Drossman DA. What is new in Rome IV. J Neurogastroenterol Motil 2017;23:151.

- Camilleri M. Opioid-induced constipation: Challenges and therapeutic opportunities. Am J Gastroenterol 2011;106:835-842.

- Andromanakos N, Skandalakis P, Troupis T, Filippou D. Constipation of anorectal outlet obstruction: Pathophysiology, evaluation and management. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2006;21:638-646.

- Sommers T, Petersen T, Singh P, et al. Significant morbidity and mortality associated with fecal impaction in patients who present to the emergency department. Dig Dis Sci 2019;64:1320-1327.

- Tracey J. Fecal impaction: Not always a benign condition. J Clin Gastroenterol 2000;30:228-229.

- Pucciani F. Descending perineum syndrome: New perspectives. Tech Coloproctol 2015;19:443-448.

- Minguez M, Herreros B, Benages A. Chronic anal fissure. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol 2003;6:257-262.

- Yun Q, Wang S, Chen S, et al. Constipation preceding depression: A population-based cohort study. EClinicalMedicine 2024;67:102371.

- Marquis P, De La Loge C, Dubois D, et al. Development and validation of the Patient Assessment of Constipation Quality of Life questionnaire. Scand J Gastroenterol 2005;40:540-551.

- Rome IV Criteria. Rome Foundation. https://theromefoundation.org/rome-iv/rome-iv-criteria/

- Aziz I, Whitehead WE, Palsson OS, et al. An approach to the diagnosis and management of Rome IV functional disorders of chronic constipation. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020;14:39-46.

- Arce DA, Ermocilla CA, Costa H. Evaluation of constipation. Am Fam Physician 2002;65:2283-2291.

- Nurko S, Zimmerman LA. Evaluation and treatment of constipation in children and adolescents. Am Fam Physician 2014;90:82-90.

- Moshiree B, Drossman D, Shaukat A. AGA clinical practice update on evaluation and management of belching, abdominal bloating, and distention: Expert review. Gastroenterology 2023;165:791-800.e3.

- Driver BE, Chittineni C, Kartha G, et al. Utility of plain abdominal radiography in adult ED patients with suspected constipation. Am J Emerg Med 2020;38:1092-1096.

- Anthony LB, Chauhan A. Diarrhea, constipation, and obstruction in cancer management. In: Olver I, ed. The MASCC Textbook of Cancer Supportive Care and Survivorship. Springer;2018:421-436.

- Alexoudi A, Kesidou L, Gatzonis S, et al. Effectiveness of the combination of probiotic supplementation on motor symptoms and constipation in Parkinson’s disease. Cureus 2023;15:e49320.

- Iancu MA, Profir M, Roşu OA, et al. Revisiting the intestinal microbiome and its role in diarrhea and constipation. Microorganisms 2023;11:2177.

- Chumpitazi CE, Henkel EB, Valdez KL, Chumpitazi BP. Soap suds enemas are efficacious and safe for treating fecal impaction in children with abdominal pain. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2016;63:15-18.

- Niv G, Grinberg T, Dickman R, et al. Perforation and mortality after cleansing enema for acute constipation are not rare but are preventable. Int J Gen Med 2013;6:323-328.

- Chan DS, Delicata RJ. Meta-analysis of antegrade continence enema in adults with faecal incontinence and constipation. J Brit Surg 2016;103:322-327.

- Shin GH, Toto EL, Schey R. Pregnancy and postpartum bowel changes: Constipation and fecal incontinence. Am J Gastroenterol 2015;110:521-529.

- Verghese TS, Futaba K, Latthe P. Constipation in pregnancy. The Obstetrician & Gynaecologist 2015;17:111-115.

- Fan W, Kang J, Xiao X, et al. Causes of constipation during pregnancy and health management. Int J Clin Exp Med 2020;13:2022-2026.

- Vazquez JC. Constipation, haemorrhoids, and heartburn in pregnancy. BMJ Clin Evid 2010;2010:1411.

- Prather CM. Pregnancy-related constipation. Curr Gastroenterol Rep 2004;6:402-404.

- Mutyala R, Sanders K, Bates MD. Assessment and management of pediatric constipation for the primary care clinician. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care 2020;50:100802.

- Chumpitazi CE, Rees CA, Camp EA, et al. Diagnostic approach to constipation impacts pediatric emergency department disposition. Am J Emerg Med 2017;35:1490-1493.

- Biggs WS, Dery WH. Evaluation and treatment of constipation in infants and children. Am Fam Physician 2006;73:469-477.

- Steurbaut L, Levy EI, De Geyter C, et al. A narrative review on the diagnosis and management of constipation in infants. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2023;17:769-783.

- Tabbers MM, DiLorenzo C, Berger MY, et al. Evaluation and treatment of functional constipation in infants and children: Evidence-based recommendations from ESPGHAN and NASPGHAN. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2014;58:258-274.

- Bolia R, Safe M, Southwell BR, et al. Paediatric constipation for general paediatricians: Review using a case‐based and evidence‐based approach. J Paediatr Child Health 2020;56:1708-1718.

- Bongers ME, de Lorijn F, Reitsma JB, et al. The clinical effect of a new infant formula in term infants with constipation: A double-blind, randomized cross-over trial. Nutr J 2007;6:1-7.

- Levy EI, Lemmens R, Vandenplas Y, Devreker T. Functional constipation in children: Challenges and solutions. Pediatric Health Med Ther 2017;8:19-27.

- Reeves PT, Kolasinski NT, Yin HS, et al. Development and assessment of a pictographic pediatric constipation action plan. J Pediatr 2021;229:118-126.

- Gatto A, Curatola A, Ferretti S, et al. The impact of constipation on pediatric emergency department: A retrospective analysis of the diagnosis and management. Acta Biomed 2022;92:e2021341.

- Santucci NR, Chogle A, Leiby A, et al. Non-pharmacologic approach to pediatric constipation. Complement Ther Med 2021;59:102711.

Constipation is a common diagnosis in the emergency department (ED) that has been steadily increasing in prevalence over the past several decades. As the morbidity and healthcare costs from this condition increase, it is important that ED physicians be aware of the workup, management, and potential complications of this common condition in adults and children alike.

Subscribe Now for Access

You have reached your article limit for the month. We hope you found our articles both enjoyable and insightful. For information on new subscriptions, product trials, alternative billing arrangements or group and site discounts please call 800-688-2421. We look forward to having you as a long-term member of the Relias Media community.