By Matthew Turner, MD, and Catherine A. Marco, MD, FACEP

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

- Colonic emergencies, such as large bowel obstruction, acute colonic pseudo-obstruction, diverticulitis, toxic megacolon, scybala, volvulus, and rectal prolapse, are encountered frequently in the emergency department.

- A thorough history and physical exam is important in the evaluation of patients with suspected colonic emergencies. This should include a discussion of current medications and colorectal symptoms, such as bowel habits and rectal bleeding.

- While abdominal X-ray can be useful as a screening tool in many colonic emergencies, computed tomography typically is the imaging modality of choice because it reliably demonstrates the diagnosis along with associated complications.

- Large bowel obstructions commonly occur secondary to malignancy.

- Acute colonic pseudo-obstruction is thought to be secondary to dysfunction of the autonomic nervous system, and treatment with neostigmine may be warranted.

- A trial of observation over provision of antibiotics may be indicated in patients without significant comorbidities presenting with uncomplicated diverticulitis.

- Toxic megacolon is a potentially fatal complication in patients with inflammatory bowel disease or Clostridioides difficile infection, which can lead to bowel perforation.

- In older adult patients presenting with vague abdominal symptoms or agitation, the clinician should maintain a high suspicion for scybala or fecal impaction because it may lead to bowel wall ischemia, necrosis, and perforation if it is undetected and untreated.

- Sigmoid volvulus is more common than cecal volvulus and has a greater likelihood for successful treatment with flexible sigmoidoscopy.

- Rectal prolapse is a clinical diagnosis, and patients without evidence of rectal strangulation or necrosis typically warrant a trial of gentle manual reduction with the use of granulated sugar.

- In a patient with a colonic emergency and evidence of concomitant peritonitis, perforation and/or intra-abdominal sepsis, management in the emergency department includes fluid resuscitation, broad-spectrum antibiotic administration, and possible surgical consultation.

Introduction

Abdominal pain is one of the most frequent chief complaints an emergency clinician will evaluate. The differential diagnosis of abdominal pain is vast, and colonic emergencies are a frequently encountered subset. Colonic emergencies have a wide range of presentation in the emergency department (ED) and often require urgent medical intervention. The emergency provider should have a thorough understanding of the evaluation and management of patients presenting with suspected colonic emergencies. Some of the most frequently encountered colonic emergencies, including large bowel obstruction, acute colonic pseudo-obstruction, diverticulitis, toxic megacolon, scybala, volvulus, hemorrhoids, rectal prolapse, and constipation, will be reviewed in this article.

Large Bowel Obstruction

Large bowel obstructions (LBOs) are significantly less common than small bowel obstruction (SBO), only accounting for approximately 20% to 25% of cases of bowel obstructions.1 However, LBOs are far more likely to require surgical intervention.2

Approximately 50% to 60% of LBOs in the United States are due to adenocarcinoma of the colon and rectum.1 LBOs are a common complication from colon cancers in general and approximately 10% to 19% of patients with colon cancer will experience complications from LBO.3 More than 75% of obstructing cancers occur distal to the splenic flexure, within the descending colon and rectosigmoid.4,5 LBO also can occur secondary to volvulus and severe diverticulitis, both of which will be discussed later in this article.5 Other causes may include extrinsic tumors compressing the bowel, severe fecal impaction, stercoral colitis, foreign bodies, and intussusception in 1% to 2% of adult cases.2,4,5 Inflammatory bowel diseases, such as ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease, may cause LBO, but such complications are extremely rare.4

Given the severe threat to morbidity and mortality that an LBO presents, it is important that it is diagnosed accurately and promptly. Early LBO may present with similar symptoms to SBOs, making it difficult to fully determine the etiology on history and physical examination.1

History and Physical Exam

While the presentation of LBO may be vague, there are four cardinal signs that physicians should understand: abdominal pain, constipation/obstipation, distension of the abdomen, and, to a lesser extent, vomiting.4 However, it is important to note that the presence of vomiting in LBO patients depends on the competency of their ileocecal valve.4 More than 75% of patients will have a competent ileocecal valve, significantly reducing the prevalence of vomiting in patients with LBO, especially when compared to SBOs.1,2,4 However, proximal tumors, in the presence of an incompetent ileocecal valve, may allow backflow of intestinal contents, resulting in a more classical presentation of SBO.2

On initial presentation to the ED, a thorough history should be obtained for patients at risk for LBO. Particular emphasis should be focused on colorectal symptoms, such as rectal bleeding, significant weight loss, history or risk factors for colon cancer, a history of recurrent diverticulitis, change in bowel movements, and symptoms such as cramping or colicky pain.6 In addition to this, the clinician also should determine if the patient has experienced any systemic symptoms, such as fever or chills, which may be indicative of a more emergent presentation such as perforation of the colon.1 Symptom onset may be abrupt or gradual.1,2 LBO due to malignancy often presents more insidiously, with patients complaining of increasing difficulty with constipation, increased abdominal distension, and failure to have significant bowel movements with over-the-counter laxatives.6 Obstructions that occur in the distal colon usually present more rapidly because of a smaller lumen and more solidified stool.1 Blockages of the proximal colon are far less common and usually are much more severe because of the lumen’s diameter and often indicate bulky obstructions.6

Once the patient’s history has been gathered, a thorough physical examination should be performed. The patient’s abdomen should be assessed for any evidence of distension or tympany.5,7 Unless contraindicated, a digital rectal exam (DRE) should be performed to assess for the possibility of stool impaction or distal masses.1 If indicated, a digital disimpaction should be performed, since severe constipation can act as a confounder or co-symptom with LBO.7 In female patients, a bimanual pelvic examination also may be included to assess for possible obstruction and/or rectovaginal fistula formation.3 Bowel sounds in these patients typically are reduced, due to the cessation of peristalsis.2 Any evidence of fever, tachycardia, or peritonitis is a particularly concerning finding highly suggestive of perforation, bowel ischemia, or strangulation and should be treated as abdominal emergencies.1,5

Laboratory Studies

Laboratory studies should include a basic metabolic panel to assess the patient’s electrolytes and renal function as well as complete blood count (CBC) to assess for anemia and leukocytosis.1,5 In patients with colonic malignancy, anemia may occur from chronic subacute blood loss. If there is any concern for ischemia, a lactic acid level should be ordered.1

Imaging

Given their ubiquity, low price, and rapidity to perform, abdominal plain film X-rays may be a useful form of initial imaging when evaluating a patient with suspected LBO.5 Dilated loops of bowel, air fluid levels, intraperitoneal air, and portal venous air may be detected on an abdominal X-ray and can expedite management if present.1,5 Abdominal X-rays have a reported sensitivity of 82% and specificity of 83% in the identification of LBO.2 However, X-rays often fail to distinguish between SBOs and LBOs, and frequently fail to identify the underlying cause.1,5

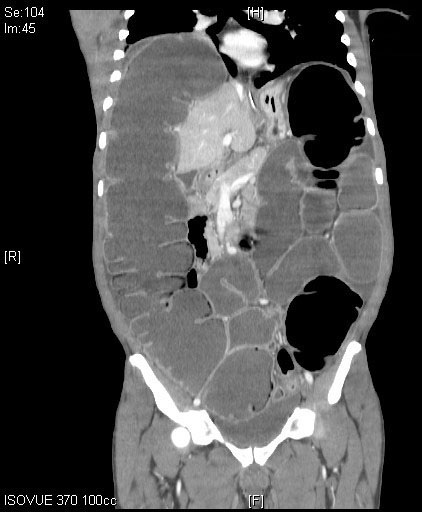

Computed tomography (CT) imaging of the abdomen and pelvis is a far more sensitive and specific tool in the assessment of LBO. (See Figures 1 and 2.) CT imaging offers significantly more information than an abdominal X-ray, including the location of the occlusion, the possible etiology of the LBO, and/or any complications from the LBO, such as perforation.1,5 CTs can localize obstructing lesions with a reported sensitivity of 96% and specificity of 97%, making them highly effective at identifying the transition point from healthy to affected bowel.2,6

Figure 1. Coronal Plane of a Computed Tomography Scan of the Abdomen and Pelvis Demonstrating a Dilated Large Bowel, Consistent with Large Bowel Obstruction |

|

Source: Image courtesy of J. Stephan Stapczynski, MD. |

Figure 2. Axial Plane of a Computed Tomography Scan of the Abdomen and Pelvis Demonstrating a Dilated Large Bowel with Air Fluid Levels |

|

Source: Image courtesy of J. Stephan Stapczynski, MD. |

Another less commonly used imaging modality includes the provision of a water-soluble contrast enema. The contrast enema is immediately followed by an abdominal plain film. This often offers some symptomatic relief and has been reported to identify the level of obstruction with 96% sensitivity and 97% specificity.5 If there is a suspected perforation, this imaging modality should be avoided.

Similarly, colonoscopy also may provide both diagnostic information and symptomatic relief to the patient after the diagnosis is made, although such imaging is outside the scope of practice of emergency physicians.1 Colonoscopy may be performed as part of the patient’s hospitalization after subspecialty consultation with surgery and gastroenterology teams.

Ultrasound is an effective screening modality for the diagnosis of LBO, with a sensitivity of 85% for detecting high-grade obstructions.8 It may be considered as a tool in unstable patients or in patients who should have radiation exposure minimized.8 However, ultrasound typically is unable to locate the transition point and/or the underlying etiology of the patient’s LBO, and advanced imaging such as CT still is recommended in the evaluation of patients with suspected LBO.8

Management

Patients with LBO often have significant third spacing and are intravascularly depleted, thus requiring significant volume resuscitation.9 A bladder catheter may be considered to monitor the patient’s urine output to determine the efficacy of resuscitative measures.8 Further supportive care should include aggressively correcting any electrolyte imbalances that are detected on the patient’s chemistry panel.8,9 Electrolyte imbalances that may be contributing to the patient’s symptoms — such as hypercalcemia or hypokalemia — should be addressed.7 Further supportive care options that may be indicated include the provision of a nasogastric (NG) tube. This should be considered in patients with significant nausea and vomiting and/or in patients with a distended stomach/small bowel secondary to a backup of intraluminal contents. NG tube placement may assist in the decompression of a patient’s stomach and reduce the risk of aspiration.7 While an excellent option for pain control, opioids may worsen constipation and bowel stasis.7 Therefore, consideration of non-narcotic pain control regimens should be considered. Ultimately, if a patient is in extreme pain, and/or with concerns of an acute surgical abdomen, the decision of narcotic provision will be based on a risk-benefit profile.

If the patient is stable, flexible sigmoidoscopy may be performed early in management under the guidance of subspecialists. This may be done without the need for deep sedation, and in cases of LBO, may provide an early diagnosis and expedite management. The procedure typically involves CO2 insufflation, given that CO2 is absorbed in the gastrointestinal tract 250 times faster than air and is less likely to cause perforation or complications.9

Adjunctive conservative management also may be considered in stable patients who are hospitalized if they are not expecting to undergo emergent surgery. These therapies include oral magnesium hydroxide, simethicone, and probiotics in hospitalized patients.8 If the patient is a candidate for such therapy, they should be provided a trial of conservative management, since these treatments have been shown to have a success rate of 40% to 70% and a significantly decreased hospital stay.8

Many patients with LBO, particularly those with evidence of ischemia, perforation, or peritonitis, will require urgent surgical consultation and likely intervention. In patients presenting with a concerning exam for peritonitis or intra-abdominal sepsis, adjunctive antibiotics with aerobic and gram-negative coverage should be provided as soon as possible in the ED while awaiting surgical consultation.9

In patients receiving palliative care or those with severe malignancy, self-expanding metal stents (SEMS) may be used as a bridging therapy or even an alternative to surgery to decompress the bowel.6 The use of SEMS often avoids the need for colostomy, giving patients a significantly improved quality of life.10 Even in patients who ultimately will undergo surgery, stents may allow time to fully prepare the patient, correct electrolyte abnormalities, and ultimately decrease surgical mortality from 20% to as low as 5%.9 Ultimately, stent insertion followed by surgery appears to be both more cost-effective and provide a higher quality of life than emergency surgery alone.9

Acute Colonic Pseudo-Obstruction

Acute colonic pseudo-obstruction (ACPO), also known as Ogilvie syndrome, presents akin to LBO, however without any evidence of mechanical obstruction.11 While the exact mechanism of ACPO remains unclear, it appears to be due to dysfunction in the autonomic nervous system.4 If left untreated, ACPO may progress to ischemia and perforation of the bowel in up to 15% of patients.11,12

Clinical Presentation

ACPO is associated with a wide range of illnesses and, therefore, the medical history of patients with suspected ACPO should be assessed carefully. Risk factors for ACPO include a history of myocardial infarction, Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, recent systemic infections by gram-negative bacteria, electrolyte imbalances, metabolic disorders, and surgeries, in addition to the use of antidepressants, anti-Parkinson drugs, and opiates.13 Older adult patients and those with significant comorbidities are at higher risk of ACPO, as well as post-surgical patients.12 ACPO in post-surgical patients most commonly occurs after cesarean delivery, suggesting that the bowel changes wrought by pregnancy may play a role in the syndrome’s development.12

Patients often present with vague abdominal symptoms, including pain, distension, and/or nausea and vomiting. Notably, up to 60% of patients will have symptoms concerning for bowel obstruction, specifically the inability to pass stool or flatus.13 In a physical exam, patients may display a wide range of findings, from high-pitched bowel sounds to reduced or absent bowel sounds, a tender or non-tender abdomen, and possibly a tympanic abdomen.13

Laboratory Studies and Imaging

ACPO often is associated with several electrolyte abnormalities and acute kidney injury, although it remains unclear whether this is a cause or effect of the disease.12 Regardless, these should be assessed in the evaluation of a patient with suspected ACPO. As well, a CBC should be obtained to evaluate for a leukocytosis. In addition, the provider can consider obtaining a C-reactive protein (CRP) level. An elevated CRP and leukocytosis may indicate colonic perforation.14

Abdominal radiographs typically will display dilation of the proximal colon.13 In addition, upright chest radiographs also may show evidence of free air under the diaphragm concerning for a perforated bowel.13 However, CT scans should be the mainstay of imaging, given their ability to accurately determine whether a mechanical obstruction is present along with concomitant complications.13 CT scans with intravenous (IV) contrast have a sensitivity of 96% and specificity of 93% in identifying ACPO.14 Water-soluble contrast enemas also may be used effectively in the diagnosis of ACPO.13

Management

The management of ACPO depends largely on the patient’s clinical presentation and the risk of ischemia and perforation.13 Conservative management should include fluid resuscitation and correction of electrolyte abnormalities, particularly hypokalemia and hypomagnesemia.14 In addition, it is important to consider the discontinuation of any medications that may be contributing to gut dysmotility.13 Laxatives, especially osmotic compounds including lactulose, should be avoided because of the risk of promoting gas production in the colon and potentially increasing the risk of perforation.13 Patients also should be placed on a nothing by mouth (NPO) status and have an NG tube placed for decompression of the proximal bowels.14 Ambulation, as well as sitting in the knee-chest position or the right and left lateral decubitus positions, may encourage passage of flatus and stool contents.14

Intravenous neostigmine, which acts as a reversible acetylcholinesterase inhibitor and therefore a parasympathomimetic, is a common treatment option, because of its ability to promote intestinal motility.12,13 Given the side effects of neostigmine — including bradycardia and hypotension — the patient’s electrocardiogram (ECG) and vital signs should be monitored carefully while being administered this medication, with atropine readily available to treat bradycardia if necessary.13 Neostigmine may be provided at either a 2 mg to 2.5 mg IV bolus over three to five minutes, with colonic motility resulting within 30 minutes in 80% of cases, or as an infusion at 0.4 mg/hour to 0.8 mg/hour over 24 hours.14

Decompressive colonoscopy may be effective in the treatment of ACPO; however, more research is required at this time.13 Surgical intervention should only be used as a last resort in cases of bowel ischemia and/or perforation.13

Diverticulitis

Diverticulitis is an increasingly common illness in the U.S. population and represents the third most common gastrointestinal discharge diagnosis seen in the ED, behind acute pancreatitis and cholelithiasis.15,16 As of 2015, it is responsible for more than 130,000 hospitalizations for abdominal pain each year in the United States.17 While particularly common in the elderly population, it also is associated with obesity, a sedentary lifestyle, use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), smoking, and poor diet.15 It also may be seen in younger patients. A 2015 study found that the majority of patients who presented to the ED with diverticulitis were younger than 65 years of age.18

The Western diet with a low amount of dietary fiber predisposes many patients to developing colonic diverticula (protrusions from the colonic wall), with an incidence of diverticulosis of approximately 33% to 66%.19-21 Diverticulitis develops when these diverticula torse and become inflamed, most commonly in the sigmoid or descending colon.19 Males appear to be more commonly affected before the age of 50 years, while females are affected after the age of 50 years.20 Up to 75% of cases of diverticulitis are uncomplicated.20 Complications of diverticulitis may include perforation, abscesses, fistulas, and obstructions, requiring emergent antibiotics and surgical consultation for possible operative intervention.19,20

Clinical Presentation

Diverticulitis often may be difficult to diagnose clinically, presenting with diffuse abdominal discomfort and nonspecific symptoms.17 In mild cases, patients often present with crampy pain in the left lower quadrant and may have a low-grade fever.21 Patients also may endorse changes in their bowel habits with diarrhea or constipation.20,22 Other symptoms may include nausea and vomiting, constant vs. intermittent pain, and even dysuria secondary to bladder irritation by the inflamed colon.22 In more severe presentations, a patient may present ill-appearing with an exquisitely tender abdominal exam. These patients may demonstrate decreased bowel sounds and peritoneal findings, such as guarding, rebound, and rigidity.21,22 Rectal exams typically are nonspecific but can demonstrate tenderness in the presence of a pelvic abscess.22 Given this generalized presentation, acute diverticulitis has a wide differential diagnosis, as noted in Table 1.

Table 1. Differential Diagnosis of Acute Diverticulitis22 |

||

Gastrointestinal |

Genitourinary |

Gynecological |

|

|

|

Patients who are immunocompromised, have a history of renal insufficiency or liver disease, or regularly use NSAIDs are at an increased risk of complications and a higher morbidity rate from diverticulitis.20 Similarly, patients with lifestyle factors, such as an elevated body mass index (BMI) and low levels of physical activity, are at a higher risk of complications from diverticulitis.22 Prior episodes of diverticulitis are not of large prognostic value, since the majority of patients presenting with complicated diverticulitis have no history of prior diverticulitis.22

History and physical examination alone appear to only be approximately 40% to 65% accurate in the diagnosis of diverticulitis.20 In the majority of suspected cases, further diagnostic testing will be necessary.22

Laboratory Studies

While laboratory testing alone is insufficient for a comprehensive diagnosis of diverticulitis, it may help physicians in assessing patients for possible complications.20 In cases of diverticulitis, a CBC may demonstrate leukocytosis. Patients also may display elevated inflammatory markers, such as CRP.20 A CRP cutoff of 170 mg/L has been demonstrated to discern between cases of mild or severe diverticulitis.24 However, it should be noted that CRP has a six- to eight-hour delay in the rise in acute disease presentations and typically reaches its maximum level approximately 48 hours into the disease process.24 As well, CRP is nonspecific and may be elevated in numerous other disease processes. Other laboratory studies that should be gathered include a basal metabolic panel including serum creatinine and glucose levels.24 A urinalysis should be ordered as well, along with a urine pregnancy test for females of child-bearing age.22

Imaging

In cases of suspected intestinal perforation, patients should have an immediate upright chest X-ray to rule out the possibility of free intra-abdominal air.22 However, because of the poor sensitivity and specificity of X-ray, abdominal CT scans with IV contrast represent the gold standard for imaging diverticulitis, with a sensitivity and specificity of up to 100%.21 Given its widespread availability and ability to reliably diagnose diverticulitis and complications that may be present, abdominal CT scan is the imaging modality of choice. Ultrasound has a reported sensitivity of 77% to 98% in detecting diverticulitis but may be limited secondary to body habitus and sonographer skill level.17 As well, ultrasound may be unable to detect deep intra-abdominal abscesses.24 Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) also may be used, since it has a similar sensitivity and specificity to that of a CT scan without the associated ionizing radiation.21 However, given its limited availability and cost, MRI may not be a feasible imaging modality.

The Hinchey Classification scale for acute diverticulitis, initially published in 1978, has since been modified with developments in imaging technology, most specifically the CT scan.21 The Modified Hinchey Classification Score is an effective means of determining the severity of acute diverticulitis.21

Imaging is extremely important in patients presenting with diverticulitis. Patients with an abscess have an inpatient mortality rate of 17%, while patients presenting with a perforation have an inpatient mortality rate of 45%.20 CT scans are reliably able to detect fat stranding, abscesses, phlegmon, intra-abdominal free fluid, free air, and fistula formation.24 While the majority of diverticulitis cases are limited to the left-sided colon, right-sided cases of diverticulitis may be seen in young, Asian populations.25

Management of Diverticulitis

Uncomplicated acute diverticulitis, without signs of abscess or perforation, and presenting solely as a confined inflammation on imaging, is a self-limiting condition. Patients without any other significant comorbidities or risk factors may be managed conservatively, without the need for antibiotic coverage, especially if they are able to tolerate oral intake and display no systemic symptoms.23,24 The majority of international guidelines no longer recommend routine antibiotics, and recommend a clear liquid diet for two to three days.26 While the routine use of antibiotics for uncomplicated diverticulitis remains common in the United States, there does not appear to be conclusive evidence to support this practice.27,28 The risk of severe complications after uncomplicated diverticulitis is approximately 4%, regardless of whether patients receive antibiotics.29 However, in cases where providers believe that patients at particular risk for a complicated course, such as immunocompromised patients, it is reasonable to consider outpatient antibiotics.26 Outpatient antibiotic selection should be tailored to provide coverage against gram-positive, gram-negative, and anaerobic bacteria.26 Providers can consider providing the patient with an initial IV antibiotic, such as carbapenem or piperacillin tazobactam, followed by a course of outpatient oral antibiotics, such as metronidazole paired with either ciprofloxacin or cefadroxil.29 Amoxicillin-clavulanate also may be considered as an alternative to the metronidazole and fluoroquinolone combination.30

Because diverticulitis with complications poses an increased risk of morbidity and mortality, CT imaging should be included in the disposition planning to determine if a patient is an appropriate candidate for outpatient management.31 Patients with uncomplicated diverticulitis who are well-appearing may be candidates for discharge with return precautions. On the other hand, hospitalization should be considered in patients with significant comorbidities, a concerning abdominal exam, poor pain control, who are older adults, or who have intractable vomiting or inability to tolerate oral antibiotics. The goal of hospitalization will include pain management, fluid repletion, bowel rest, and provision of antibiotics.23 Previous research held that patients with at least two episodes of acute diverticulitis should be considered for prophylactic surgery because of the possibility of developing complicated disease; however, recent findings indicate that the recurrence rate of acute diverticulitis is rare.22

Moreover, patients with moderate cases of diverticulitis, including those with small abscesses (less than 5 cm) may be managed with a conservative regimen consisting of antibiotics and easily digestible food.24 Anti-inflammatories (such as mesalazine), probiotics, and a high-fiber diet also appear to be promising conservative therapies, although further research is needed.21,22 Antibiotic coverage should cover for anaerobes, and both gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria, as noted earlier.24 Disposition for these patients should take into account the aforementioned factors. In patients with larger abscesses (greater than 5 cm), there is a possibility that the antibiotics are unable to reach adequate therapeutic concentration within them.24 Thus, patients with abscesses larger than 5 cm should be considered as candidates for CT-guided percutaneous drainage.21 These patients should be hospitalized with antibiotics, bowel rest, and abscess drainage, and may later be considered for elective colonic resection.23

Hinchey stages III and IV classically present with peritonitis secondary to a colonic perforation.23 In these severe cases, emergent surgery typically is required.22 While primary resection and anastomosis has been the standard surgery for decades, new research has shown that patients with peritonitis with a Hinchey score of I to III may be managed with laparoscopic washout and drain placement rather than a more complex surgery.22 However, the determination of open surgery vs. a minimally invasive approach remains outside the scope of practice of ED physicians and ultimately should be determined by the surgical team.

Toxic Megacolon

Toxic megacolon (TM) is defined as a non-obstructive, acute dilation of the transverse colon to greater than 6 cm in diameter, along with manifestations of systemic toxicity.32 While the exact pathophysiological mechanism remains unknown, TM may occur as a complication of a number of colonic disease processes, including inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), infectious or ischemic colitis, diverticulitis, Clostridioides difficile (C. diff) pseudomembranes, prior radiation, or even colon cancer.32 IBD appears to be the most common predisposing factor, present in 48% of TM cases.33 It remains unclear whether ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease is associated with a higher risk of TM.33 Of note, C. diff–associated TM has been growing in frequency in recent years and appears to have a worse clinical course.32 Narcotics and anticholinergic medications that reduce gut motility, as well as electrolyte abnormalities such as hypokalemia and recent procedures such as colonoscopy and barium enema appear to increase the risk of developing TM.32 The prevalence of TM increases with age; women appear to have a higher risk of mortality.34 TM is a medical emergency, with mortality rates ranging from 6% to 80%.33 These patients will require aggressive management in the ED.

Clinical Presentation

The most common symptom of TM is severe bloody diarrhea.34 Patients with TM typically present acutely unwell, with nonspecific signs and symptoms of an acute abdominal condition, including pain, diarrhea, hematochezia, emesis, and distension.33 Systemic symptoms such as fever, tachycardia, and evidence of volume depletion also are likely to be present.33

Physicians should determine the patient’s abdominal history, including any history of IBD. Any change in the patient’s bowel habits should be determined. If the patient has had three or more unformed stools within the past 24 hours, they may be experiencing diarrhea secondary to an underlying C. diff infection and should have stool testing for C. diff toxin.33 It also should be determined if the patient is taking any analgesics or has any evidence of altered mental status, since this may conceal further evidence of TM.34 If patients are immunocompromised, they may have a risk of cytomegalovirus (CMV) colitis or C. diff colitis, both of which are difficult to manage medically and may require surgery.34 Pregnant women presenting with concerns for TM should be considered for urgent surgical intervention because of the risk of fetal complications.34

In cases of suspected TM, both history and physical exam are not sufficient for diagnosis. Ultimately, the diagnostic criteria of TM depends on a combination of the physical exam, laboratory studies, and imaging, as shown in Table 2.34

Table 2. Diagnostic Criteria of Toxic Megacolon34 |

||

Radiographic Evidence |

Any Three of the Following |

Any of the Following |

|

|

|

Laboratory Studies

A CBC should be ordered to assess for the degree of leukocytosis as well as the possibility of anemia from blood loss in the colon.33 Because of the loss of the colon’s ability to reabsorb salt and water, systemic TM may present with significant electrolyte abnormalities, including hypokalemia, contraction metabolic alkalosis, and elevated levels of blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and creatinine due to hypovolemia.32 Approximately 75% of patients eventually will develop hypoalbuminemia because of protein loss and decreased albumin production from the liver — resulting from both inflammation and malnutrition.32 Inflammatory markers, including erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and CRP, may be elevated in cases of suspected TM.34 Acidosis, hypoalbuminemia, high BUN levels, and low serum carbon dioxide levels are associated with high mortality and should be included as part of the workup.32,34 Serum lactate also should be obtained and may guide resuscitation in patients with significant volume depletion or intra-abdominal sepsis from the TM.34 If the patient is at risk for pseudomembranes, stool samples also should be gathered and tested for the presence of C. diff.33

Imaging

CT imaging of the abdomen and pelvis with contrast is the modality of choice in cases of suspected TM.34 In cases of TM, CT may demonstrate colonic distension greater than 6 cm, loss of colonic haustrae, evidence of bowel wall thickening, fat stranding, air fluid levels, and segmental colonic wall thinning.33,34

Abdominal X-rays also may be used as a screening tool to quickly assess colonic dilation or free air.33 Colonoscopy should be avoided because of the risk of perforation, but a limited proctoscopy or sigmoidoscopy may be considered for the diagnosis of inflammatory vs. infectious etiology for the TM after subspecialty consultation.34

Management

The management of TM should be focused on five primary goals, as noted in Table 3.32

Table 3. Goals of Toxic Megacolon Management in the Emergency Department Setting32 |

|

Goals |

Management |

1. Reduce colonic distension to prevent perforation |

Bowel rest, NG tube34 |

2. Cease any antibiotics that may cause Clostridioides difficile |

Stop antibiotics that may cause Clostridioides difficile |

3. Correct fluid or electrolyte disturbances |

IV fluids, electrolytes |

4. Treat toxemia/precipitating factors |

If concern for IBD etiology: Hydrocortisone 100 mg IV every 6-8 hours If concern for infectious etiology: Refrain from steroids34 |

5. Initiate broad spectrum IV antibiotics and IV steroids |

|

NG: nasogastric; IV: intravenous; IBD: inflammatory bowel disease |

|

Bowel rest and the placement of an NG tube should be ordered to reduce both air and fluid in the gastrointestinal tract, reducing the risk of perforation.34 Seventy-six percent of infectious causes of TM are caused by C. diff, making it imperative that antibiotics with the greatest incidence of leading to C. diff infection be discontinued.32 Any electrolyte abnormalities and evidence of hypovolemia should be corrected with electrolyte and fluid repletion as needed.32

In cases where the patient’s TM likely is secondary to IBD, patients may be given IV hydrocortisone 100 mg every six to eight hours, since this safely reduces the diameter of the colon without increasing the risk of perforation.34 However, steroid treatment should be used with caution because it is strictly contraindicated in cases of TM that may be due to any infectious etiology, including C. diff.34 If there is any diagnostic uncertainty to the underlying etiology for the patient’s TM, steroids should be avoided.

In all cases of TM, patients should be started on empiric antibiotic coverage because of the risk of sepsis in patients with TM.34 Ultimately, patients presenting with TM will require inpatient management, given the need for serial exams and monitoring of laboratory studies along with possible repeat imaging.34

While approximately half of TM cases resolve with medical therapy alone, surgical intervention is indicated in cases of perforation, necrosis, worsening ischemia, peritoneal signs, or worsening abdominal exam.34 Patients with an active infection will require corrective surgery in up to 20% of cases, with associated mortality rates ranging from 35% to 80%.32 Patients with perforation of their colon are at an exceptionally high risk of mortality.32 Even patients initially successfully managed with medical therapy alone may require later surgical intervention.34 If necessary, surgery should be performed as early as possible. Surgeries performed prior to patients developing a colonic perforation have a mortality rate of 8%, compared to a mortality rate of 40% seen in patients who undergo surgeries after colonic perforation.34

Other possible intervention for TM includes the possibility of hyperbaric oxygen therapy and IV immune globulin, but further research is required before these may become standard practice.34

Fecal Impaction/Scybala

Prolonged fecal impaction, or particularly hard fecal masses, often referred to as scybala, can lead to significant colonic complications, particularly from the ischemic pressure that they exert on the intestinal wall, in a process known as stercoral colitis.25,35 In the most severe cases, this can lead to ulceration and perforation of the bowels, followed by sepsis and death.25

Fecal impaction (FI), defined as a mass of compacted fecal material at any level of the intestine that cannot be spontaneously evacuated, is a common presentation in the ED.36 FI is particularly common in older adult populations; by some estimates, approximately half of all institutionalized older adult patients will experience FI each year.37 Other groups at risk include children, patients with neurological disorders, and patients with previous damage to the gastrointestinal tract from prior surgeries, Chagas disease, and systemic disorders such as scleroderma, dementia, Parkinson’s disease, hypothyroidism, history of stroke, and Alzheimer’s disease.36,38,39 Patients taking opiates, anticholinergics, calcium channel blockers, oral iron supplements, and a number of other medications also are at higher risk for developing FI.38

The primary mechanism through which scybala/FI produces its effects is through an increase in the colon’s intraluminal pressure, leading to ischemic effects on capillary perfusion within the colonic wall, which in the most extreme cases may lead to ulceration and perforation.36 In cases of stercoraceous perforation, the perforation of the colonic wall occurs secondary to a large fecal mass, without evidence of any other underlying cause.36 The obstructed bowel also may compress other intra-abdominal structures through simple mass effect.36 Ultimately, this may lead to a downstream effect where scybala/FI may contribute to the development of TM, volvulus, and other colonic emergencies.36

Stercoral colitis (SC) is one such complication of FI. Typically due to the sequelae of chronic constipation, SC develops when impacted stool leads to inflammation of the colonic wall.40 In the most severe cases, patients may develop necrosis, perforation, and sepsis, with a mortality rate in excess of 60%.40

Clinical Presentation

The most common presentation across all age groups is abdominal pain, followed by constipation and nausea/vomiting.36 Patients with a history of chronic constipation appear to be at higher risk for more severe complications.36 However, scybala/FI may paradoxically present with diarrhea, due to significant rectal distension causing prolonged relaxation of the internal anal sphincter. Older adult patients presenting with anal incontinence and diarrhea may have their symptoms secondary to an undiagnosed scybala/FI. Unfortunately, digital disimpaction in these patients actually may worsen the damage to the already stressed internal anal sphincter.36

Other atypical clinical presentations of FI include urinary retention or overflow incontinence, worsening delirium, anorexia and dysphagia, and syncope.38 Patients often do not present with abdominal pain. One review of stercoral colitis secondary to scybala/FI demonstrated that 62.1% of patients did not present with abdominal pain.35 Complaints may be more generalized, with altered mental status, weakness, urinary retention, or other complaints not clearly related to gastrointestinal issues often being the patient’s main chief concern.35 Patients with dementia may present with increasing agitation, confusion, or hemodynamic instability secondary to autonomic dysreflexia.39 Many patients with complications such as SC may even be asymptomatic, with up to 60% denying any abdominal pain.40

History should include any changes in the patient’s bowel habits, associated gastrointestinal symptoms, and surgical history.39 As part of the history, a thorough review of the patient’s medications also should be done. Physicians should pay particular attention to opiates, anticholinergics, diuretics, and supplements that may contribute to the development of constipation.38 A number of other risk factors may lead to the development of scybala/FI, including inadequate hydration and fiber intake, impaired mobility, and other factors listed in Table 4.39

Table 4. Factors that May Contribute to Scybala/Fecal Impaction39 |

||

Chronic Constipation |

Anatomic Abnormalities |

Other Factors |

Hypothyroidism, diabetes mellitus, hypercalcemia, porphyria |

Megarectum – Chagas disease, Hirschsprung disease |

Pelvic floor dysfunction |

Inadequate fluid and fiber intake |

Anorectal strictures |

Abnormal rectal sensation secondary to Crohn’s disease |

Medications |

Malignancy |

|

Neurogenic causes: spinal cord injury, multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease |

||

The patient’s physical exam should assess for any systemic symptoms, including tachycardia and alterations in blood pressure that may indicate dehydration or discomfort.39 A focused abdominal exam should be performed — in some cases, the rectosigmoid may be palpated in the left lower quadrant if it is adequately filled with stool.39 However, the physical exam may be unreliable in some patients. Evidence of perforation, including peritoneal signs, often are absent.39 The patient’s physical exam also may be grossly unremarkable in these cases, with approximately 25% of patients in one 2023 review displaying no reproducible abdominal tenderness.35 DRE often confirms the presence of firm or clay-like fecal material in the rectal vault.1 Although the majority of FI/scybala occur in the rectal vault, an unremarkable DRE does not exclude this condition, given that it can occur anywhere within the intestines.39

Ultimately, even in cases of a benign physical exam, physicians should have a high index of suspicion for further testing and imaging, particularly in patients with a large number of risk factors.35

Laboratory Studies and Imaging

Laboratory studies should include a CBC to evaluate for evidence of leukocytosis, as well as a basic metabolic panel (BMP) to assess for evidence of dehydration or significant electrolyte abnormalities.39 Lactate levels also may be drawn in cases of suspected perforation or sepsis and can aid in diagnosing ischemia of the bowel wall.35,41 In cases of suspected complications such as SC or concomitant sepsis, blood cultures also may be considered.40

Ultimately, imaging is the most significant step in diagnosis. While abdominal X-ray may show evidence of significant fecal burden and obstruction, CT imaging is the modality of choice.39 Significant impaction should be suspected when the fecal material has a diameter equal to or greater than the colon on CT imaging.4 Many complications such as SC can be diagnosed only with imaging because of their vague presentation.40

Management

The majority of guidance regarding treatment of scybala/FI is focused on treating the underlying problem of constipation.35 In cases without evidence of severe complications, patients may be treated with conservative measures, such as manual disimpaction and the administration of enemas and laxatives.35 Water-soluble contrast enema may be used for more proximal impactions as both a diagnostic and therapeutic treatment.1 Patients may require admission for close monitoring, particularly in cases with SC found on imaging.40

In severe cases without evidence of bowel obstruction, patients may require fluoroscopic disimpaction under anesthesia.4 Patients presenting with perforation or peritonitis will require emergent surgical consultation for possible exploratory laparotomy.1

Sigmoid and Cecal Volvulus

Volvulus, or “a twist in the bowel,” has been documented in the medical literature since the Egyptian Ebers Papyrus from more than 3,500 years ago.42 Approximately 10% to 17% of cases of LBO are due to volvulus.5 The vast majority of adult cases of volvulus can be categorized into either sigmoid or cecal volvulus, which account for 60% to 75% and 25% to 30% of cases of volvulus, respectively.43 The transverse colon experiences volvulus much less frequently, in approximately 5% of all documented cases.43 Volvulus at the splenic flexure also is rare, accounting for less than 1% of cases.11 Volvulus has an extremely wide incidence across the world; while relatively uncommon in the West, in the “volvulus belt” of Africa, South America, Russia, Eastern Europe, India, Brazil, and the Middle East, colonic volvulus accounts for 13% to 42% of all intestinal obstructions.44

Acute sigmoid volvulus, occurring where the sigmoid colon torses around the mesenteric axis, is the third most common cause of LBO.45 Risk factors for sigmoid volvulus include advanced age, institutionalized men, laxative abuse, a high-fiber diet, constipation, previous abdominal surgeries, diabetes, dementia, and schizophrenia.42,45,46 While uncommon in children, it may occur in those with a history of Hirschsprung’s or Chagas disease.47 If not detected early, acute sigmoid volvulus may progress to ischemia, gangrene, and perforation of the bowel if left untreated.45 Given the risk of closed-loop obstruction and the low likelihood of spontaneous detorsion occurring in only 2% of cases, the majority of these patients will require intervention.42,44

Cecal volvulus, due to an axial twisting of the cecum, ascending colon, and terminal ileum around the mesentery, is significantly less common than sigmoid volvulus.48 This torsion, often a full 360 degrees, causes strangulation of the bowel in a closed-loop obstruction pattern.46 It has a mortality rate that can be as high as 30%.46 Many of the same risk factors for sigmoid volvulus — including a history of chronic constipation and a high-fiber diet — also act as predisposing factors for cecal volvulus.46

Clinical Presentation

On presentation, a thorough abdominal history should be gathered, including prior episodes of volvulus, a history of chronic constipation, and psychotropic medications.44 Sigmoid volvulus is more common in older adult men, while cecal volvulus is more common in younger women of child-bearing age. Any history of pregnancy should be determined, because of the possibility of a gravid uterus displacing the cecum and increasing the incidence of cecal volvulus.49

The most common presenting complaints for acute sigmoid volvulus include sudden abdominal pain, distension, and constipation.45 Other common complaints include nausea and vomiting, diarrhea, and anorexia.42 On physical exam, these patients often display asymmetrical abdominal distension, tympany, an empty rectum on DRE, evidence of dehydration, and acute abdominal tenderness.45 Patients with rebound tenderness and guarding, or rectal melanotic stool, may have peritonitis or perforation.42

Sigmoid volvulus can be clinically classified into three categories: subacute, acute, and fulminating, as noted in Table 5.47 Of the three categories, fulminating is the most emergent, with signs of peritonitis and shock occurring due to severe ischemia and perforation of the bowel wall.47

Table 5. Classifications of Sigmoid Volvulus47 |

|||

Subacute Sigmoid Volvulus |

Acute Sigmoid Volvulus |

Fulminating Sigmoid Volvulus |

|

Presentation |

Elderly patient with history of chronic constipation, volvulus |

Younger patient, first episode of sigmoid volvulus, symptoms of obstruction |

Signs of peritonitis and shock secondary to severe ischemia, perforation |

Course |

Benign, indolent |

Sudden onset, rapid course |

Rapidly progressing |

Initial Management |

Decompression |

Decompression |

Surgical management |

Unfortunately, cecal volvulus has a much more variable range of presentation, and as a result often is delayed in diagnosis and treatment, contributing to a higher mortality than other cases of volvulus.48 Patients still may experience generalized abdominal symptoms, displaying significant pain, constipation, nausea, vomiting, and distension, with similar findings to sigmoid volvulus on exam.46 In some cases, the patient’s symptoms may wax and wane unpredictably, further complicating the clinical assessment.44 Unfortunately, an absence of peritoneal signs often may lead to a delay in diagnosis.44

Laboratory Studies and Imaging

While laboratory testing is non-diagnostic in these patients, it still will display any evidence of electrolyte abnormalities, leukocytosis, and further evidence of bowel ischemia and sepsis.44

A simple abdominal radiograph is diagnostic of acute sigmoid volvulus in 57% to 90% of cases, presenting with the classic “coffee bean sign.”49,50 (See Figure 3.) These patients will display a dilated sigmoid colon and also may display multiple air-fluid levels within the large and small bowels.42 CT imaging also may be used, with a typical “whirl pattern” in the colon indicating the presence of sigmoid volvulus. (See Figure 4.) CT scans have been reported to be diagnostic in nearly 100% of cases.42

Figure 3. Abdominal X-Ray Demonstrating Coffee Bean Appearance Consistent with Sigmoid Volvulus |

|

Source: Image courtesy of J. Stephan Stapczynski, MD. |

Figure 4. Scout Film from a Computed Tomography of the Abdomen Demonstrating a Dilated Loop of Bowel in the Shape of a Coffee Bean |

|

Source: Image courtesy of J. Stephan Stapczynski, MD. |

Abdominal radiographs have less utility in the diagnosis of cecal volvulus than in acute sigmoid volvulus.46 CT scanning is the preferred imaging modality in suspected cases of cecal volvulus, with a sensitivity of approximately 90%.46

Sigmoid Volvulus Management

For thousands of years, sigmoid volvulus has been treated primarily with untwisting of the bowels. Hippocrates notably used a suppository and anal insufflation with air to treat this condition.42 In 85% to 95% of sigmoid volvulus cases, flexible sigmoidoscopy is able to successfully detorse the volvulus. However, this procedure is strictly contraindicated in patients with any evidence of perforation or peritonitis.9 The procedure also is associated with a 60% recurrence rate, so these patients often still may require surgical resection of their sigmoid volvulus.9 Given the recurrence of sigmoid volvulus, an increasing number of surgeons are opting for definitive operative management, even in patients not presenting with gangrene, peritonitis, or any other severe complications.42

Colonoscopy also is effective in more than 70% of patients with sigmoid volvulus, allowing for colonic decompression as well as evaluation of the mucosa for any evidence of ischemia.45

Other methods of nonoperative detorsion include rectal tubes, barium enemas, and flexible sigmoidoscopy, although none appear to be as effective as flexible sigmoidoscopy.45

Management of Cecal Volvulus

Unlike with sigmoid volvulus, decompression often is ineffective in patients with cecal volvulus, with colonoscopies providing relief in only 30% of cases.9 Given the high rate of ischemia and complications in these patients, surgical intervention and resection should be the mainstay of definitive management.9 Temporizing measures in the ED may include fluid and electrolyte repletion, as well as placement of an NG tube to aid in decompressing the bowel.46

Other Colonic Emergencies

Hemorrhoids

Hemorrhoids, swollen veins in the anus and lower rectum, are extremely common in the United States, with up to one in three Americans displaying them on screening colonoscopy.51 Normally thought to be benign structures that act to maintain continence in healthy individuals, evidence suggests that they may become pathologic in the setting of a low-fiber diet and chronic constipation.51 However, evidence remains limited, and the true etiology of hemorrhoids remains largely unclear.51

When they become pathologic, hemorrhoids may present with rectal pain, rectal puruitus, a sensation of stool leakage, mucus, prolapse, or painless bright-red rectal bleeding.51,52 These may be easily assessed through a physical exam of the anus at rest and during straining. Internal hemorrhoids may be graded by the degree to which they prolapse. (See Table 6.)

Table 6. Grading of Internal Hemorrhoids51 |

|

Internal Hemorrhoid Grade |

Degree of Prolapse |

Grade I |

Does not prolapse below dentate line – only visible on colonoscopy and anoscopy |

Grade II |

Prolapses below dentate line, reduces spontaneously |

Grade III |

Prolapses below dentate line, requires manual reduction |

Grade IV |

Prolapses below dentate line, unable to reduce |

The majority of hemorrhoids may be treated with conservative management, including dietary modification, avoiding straining during defecation, and fiber supplementation. Many patients may need referral for treatments such as cryotherapy, sclerotherapy, ligation, and other outpatient treatments.51

Grade III and IV internal hemorrhoids may become strangulated if the prolapsed hemorrhoid continues to protrude until the vascular supply is compromised. These patients often require urgent hemorrhoidectomy, which will require surgery under general anesthesia.52

External hemorrhoids may present with acute thrombosis, with patients complaining of significant anal pain and displaying an exquisitely tender blue lump at the anal verge.52 Depending on the intensity of the patient’s discomfort, the patient may require excision of the thrombosed hemorrhoid for pain relief. Conservative measures also may be prescribed, including topical lidocaine, topical steroids, NSAIDs, warm sitz bath, and dietary modifications.52

Rectal Prolapse

Rectal prolapse, defined as a full-thickness protrusion of the rectum through the anus, may be mistaken for prolapsed internal hemorrhoids.53 However, rectal prolapses will contain a full-thickness wall with notable concentric rings, giving them a strikingly different presentation than prolapsed internal hemorrhoids.52

Often seen in women and in the older adult population, rectal prolapse is a clinical diagnosis. The physical exam should focus on attempting to reproduce the symptoms, typically while the patient strains, either in a lateral/jack-knife position, or on the toilet.53 The majority of cases will require surgical repair.53

When seen in the ED, providers should attempt to manually reduce any persistently prolapsed rectums so long as there is no evidence of rectal ischemia. The use of granulated sugar to reduce the edema of rectal prolapses, and thus significantly facilitate manual reduction, has been well documented for decades.54 Rectal prolapses, particularly in patients with a high resting sphincter tone, have a significant risk of strangulation.53 Any cases of rectal prolapse where there is evidence of incarceration, strangulation, or ischemia should have an urgent surgical evaluation performed.53

Constipation

While constipation is an extremely common presentation to the ED, with more than 1.3 million presentations in the United States yearly, the vast majority of cases may be safely and effectively managed with conservative outpatient treatment.55 However, physicians should be aware of red flag symptoms that may indicate a more serious etiology, including bloody stools, anemia, weight changes, a family history of colon cancer, any change in bowel habits after the age of 50 years, inability to pass flatus, or any concerns for LBO or SBO.56,57 Any patients presenting with these symptoms, or with a serious clinical constellation, should have an expanded diagnostic evaluation.

Conclusion

Colonic emergencies include a wide range of diseases and often can be life-threatening. The emergency clinician should perform a thorough history and physical exam in an attempt to elucidate the etiology of these complaints. A physical exam often is not sufficient, and imaging often is required for a full diagnosis. Treatments may range from conservative management to urgent surgical intervention, depending on the diagnosis and presence of concomitant complications.

Matthew Turner, MD, is an emergency medicine resident, Department of Emergency Medicine, Penn State College of Medicine, Hershey, PA.

Catherine A. Marco, MD, is Professor, Department of Emergency Medicine, Penn State Health, Hershey Medical Center, Hershey, PA.

References

- Johnson WR, Hawkins AT. Large bowel obstruction. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2021;34:233-241.

- Jaffe T, Thompson WM. Large-bowel obstruction in the adult: Classic radiographic and CT findings, etiology, and mimics. Radiology. 2015;275:651-663.

- Gainant A. Emergency management of acute colonic cancer obstruction. J Visc Surg. 2012;149:e3-e10.

- Ramanathan S, Ojili V, Vassa R, Nagar A. Large bowel obstruction in the emergency department: Imaging spectrum of common and uncommon causes. J Clin Imag Sci. 2017;7:15.

- Yeo HL, Lee SW. Colorectal emergencies: Review and controversies in the management of large bowel obstruction. J Gastrointest Surg. 2013;17:2007-2012.

- Baer C, Menon R, Bastawrous S, Bastawrous A. Emergency presentations of colorectal cancer. Surg Clin North Am. 2017;97:529-545.

- Ferguson HJ, Ferguson CI, Speakman J, Ismail T. Management of intestinal obstruction in advanced malignancy. Ann Med Surg. 2015;4:264-270.

- Jackson PG, Raiji MT. Evaluation and management of intestinal obstruction. Am Fam Physician. 2011;83:159-165.

- Yeo HL, Lee SW. Colorectal emergencies: Review and controversies in the management of large bowel obstruction. J Gastrointest Surg. 2013;17:2007-2012.

- Geraghty J, Sarkar S, Cox T, et al. Management of large bowel obstruction with self-expanding metal stents. A multicentre retrospective study of factors determining outcome. Colorectal Dis. 2014;16:476-483.

- Vogel JD, Feingold DL, Stewart DB, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for colon volvulus and acute colonic pseudo-obstruction. Dis Colon Rectum. 2016;59:589-600.

- Wells CI, O’Grady G, Bissett IP. Acute colonic pseudo-obstruction: A systematic review of aetiology and mechanisms. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23:5634.

- De Giorgio R, Knowles CH. Acute colonic pseudo-obstruction. J Brit Surg. 2009;96:229-239.

- Pereira P, Djeudji F, Leduc P, et al. Ogilvie’s syndrome – acute colonic pseudo-obstruction. J Visc Surg. 2015;152:99-105.

- Hirsch W, Nee J, Ballou S, et al. Emergency department burden of gastroparesis in the United States, 2006 to 2013. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2019;53:109-113.

- Peery AF, Dellon ES, Lund J, et al. Burden of gastrointestinal disease in the United States: 2012 update. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:1179-1187.

- Cohen A, Li T, Stankard B, Nelson M. A prospective evaluation of point-of-care ultrasonographic diagnosis of diverticulitis in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2020;76:757-766.

- Schneider EB, Singh A, Sung J, et al. Emergency department presentation, admission, and surgical intervention for colonic diverticulitis in the United States. Am J Surg. 2015;210:404-407.

- Bauer VP. Emergency management of diverticulitis. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2009;22:161-168.

- Long B, Werner J, Gottlieb M. Emergency medicine updates: Acute diverticulitis. Am J Emerg Med. 2024;76:1-6.

- Klarenbeek BR, de Korte N, van der Peet DL, Cuesta MA. Review of current classifications for diverticular disease and a translation into clinical practice. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2012;27:207-214.

- Humes DJ, Spiller RC. The pathogenesis and management of acute colonic diverticulitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;39:359-370.

- Khalil HA, Yoo J. Colorectal emergencies: Perforated diverticulitis (operative and nonoperative management). J Gastrointest Surg. 2014;18:865-868.

- Sartelli M, Weber DG, Kluger Y, et al. 2020 update of the WSES guidelines for the management of acute colonic diverticulitis in the emergency setting. World J Emerg Surg. 2020;15:1-8.

- Maddu KK, Mittal P, Shuaib W, et al. Colorectal emergencies and related complications: A comprehensive imaging review — imaging of colitis and complications. Am J Roentgenol. 2014;203:1205-1216.

- You H, Sweeny A, Cooper ML, et al. The management of diverticulitis: A review of the guidelines. Med J Aust. 2019;211:421-427.

- Young-Fadok TM. Diverticulitis. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1635-1642.

- Desai M, Fathallah J, Nutalapati V, Saligram S. Antibiotics versus no antibiotics for acute uncomplicated diverticulitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2019;62:1005-1012.

- Strate LL, Morris AM. Epidemiology, pathophysiology, and treatment of diverticulitis. Gastroenterology. 2019;156:1282-1298.

- Gaber CE, Kinlaw AC, Edwards JK, et al. Comparative effectiveness and harms of antibiotics for outpatient diverticulitis: Two nationwide cohort studies. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174:737-746.

- Sirany AME, Gaertner WB, Madoff RD, Kwaan MR. Diverticulitis diagnosed in the emergency room: Is it safe to discharge home? J Am Coll Surg. 2017;225:21-25.

- Doshi R, Desai J, Shah Y, et al. Incidence, features, in-hospital outcomes and predictors of in-hospital mortality associated with toxic megacolon hospitalizations in the United States. Intern Emerg Med. 2018;13:881-887.

- Argyriou O, Lingam G, Tozer P, Sahnan K. Toxic megacolon. Br J Surg. 2024;111:znae200.

- Desai J, Elnaggar M, Hanfy AA, Doshi R. Toxic megacolon: Background, pathophysiology, management challenges and solutions. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2020;13:203-210.

- Keim AA, Campbell RL, Mullan AF, et al. Stercoral colitis in the emergency department: A retrospective review of presentation, management, and outcomes. Ann Emerg Med. 2023;82:37-46.

- Serrano Falcón B, Barceló López M, Mateos Muñoz B, et al. Fecal impaction: A systematic review of its medical complications. BMC Geriatr. 2016;16:4.

- Sommers T, Petersen T, Singh P, et al. Significant morbidity and mortality associated with fecal impaction in patients who present to the emergency department. Dig Dis Sci. 2019;64:1320-1327.

- Salvi F, Petrino R, Conroy SP, et al. Constipation: A neglected condition in older emergency department patients. Intern Emerg Med. 2024;19:1977-1986.

- Obokhare I. Fecal impaction: A cause for concern? Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2012;25:53-58.

- Bae E, Tran J, Shah K. Stercoral colitis in the emergency department: A review of the literature. Int J Emerg Med. 2024;17:3.

- Naseer M, Gandhi J, Chams N, Kulairi Z. Stercoral colitis complicated with ischemic colitis: A double-edge sword. BMC Gastroenterol. 2017;17:1-6.

- Larkin JO, Thekiso TB, Waldron R, et al. Recurrent sigmoid volvulus —early resection may obviate later emergency surgery and reduce morbidity and mortality. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2009;91:205-209.

- Ramanathan S, Ojili V, Vassa R, Nagar A. Large bowel obstruction in the emergency department: Imaging spectrum of common and uncommon causes. J Clin Imaging Sci. 2017;7:15.

- Perrot L, Fohlen A, Alves A, Lubrano J. Management of the colonic volvulus in 2016. J Visc Surg. 2016;153:183-192.

- Lou Z, Yu ED, Zhang W, et al. Appropriate treatment of acute sigmoid volvulus in the emergency setting. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:4979.

- Solis Rojas C, Vidrio Duarte R, García Vivanco DM, Montalvo-Javé EE. Cecal volvulus: A rare cause of intestinal obstruction. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2020;14:206-211.

- Abdelrahim A, Zeidan S, Qulaghassi M, et al. Dilemma of sigmoid volvulus management. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2022;104:95-99.

- Zabeirou AA, Belghali H, Souiki T, et al. Acute cecal volvulus: A diagnostic and therapeutic challenge in emergency: A case report. Ann Med Surg. 2019;48:69-72.

- Halabi WJ, Jafari MD, Kang CY, et al. Colonic volvulus in the United States: Trends, outcomes, and predictors of mortality. Ann Surg. 2014;259:293-301.

- Lieske B, Antunes C. Sigmoid Volvulus. In: StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing. May 28, 2023.

- Sandler RS, Peery AF. Rethinking what we know about hemorrhoids. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17:8-15.

- Lohsiriwat V. Anorectal emergencies. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:5867.

- Bordeianou L, Hicks CW, Kaiser AM, et al. Rectal prolapse: An overview of clinical features, diagnosis, and patient-specific management strategies. J Gastrointest Surg. 2014;18:1059-1069.

- Coburn III WM, Russell MA, Hofstetter WL. Sucrose as an aid to manual reduction of incarcerated rectal prolapse. Ann Emerg Med. 1997;30:347-349.

- Zhou AZ, Lorenz D, Simon NJ, Florin TA. Emergency department diagnosis and management of constipation in the United States, 2006-2017. Am J Emerg Med. 2022;54:91-96.

- Bharucha AE, Wald A. Chronic constipation. Mayo Clin Proc 2019;94:2340-2357.

- Gonzalez CE, Halm JK. Constipation in cancer patients. In: Todd KH, Thomas Jr. CR, eds. Oncologic Emergency Medicine: Principles and Practice. Springer International Publishing;2016:327-332.

Abdominal pain is one of the most frequent chief complaints an emergency clinician will evaluate. Some of the most frequently encountered colonic emergencies, including large bowel obstruction, acute colonic pseudo-obstruction, diverticulitis, toxic megacolon, scybala, volvulus, hemorrhoids, rectal prolapse, and constipation, will be reviewed in this article.

Subscribe Now for Access

You have reached your article limit for the month. We hope you found our articles both enjoyable and insightful. For information on new subscriptions, product trials, alternative billing arrangements or group and site discounts please call 800-688-2421. We look forward to having you as a long-term member of the Relias Media community.