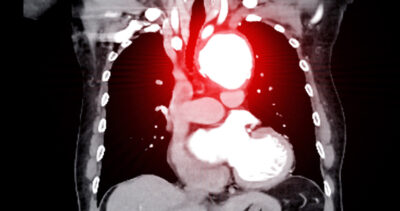

A large, cross-sectional study of adults by aortic computed tomography angiography has shown that aortic aneurysms (AAs) are more frequent in men than women. While increasing age and body surface area were common risk factors for AA, hypertension was associated with thoracic AA, and hypercholesterolemia and smoking were risk factors for abdominal AA.

ABSTRACT & COMMENTARY

Clarifying the Risk of Aortic Aneurysm Development

October 15, 2024