By Jeffrey Zimmet, MD, PhD

Associate Professor of Medicine, University of California, San Francisco; Director, Cardiac Catheterization Laboratory, San Francisco VA Medical Center

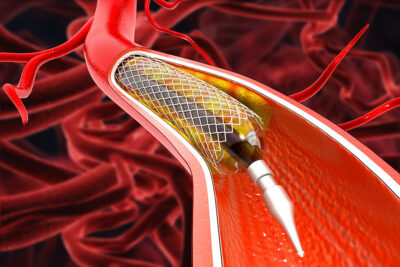

In this randomized, open-label trial of patients with primarily stable atherosclerotic coronary disease, stenting compared with medical therapy of nonobstructive lesions with imaging markers of plaque vulnerability resulted in a lower incidence of the composite endpoint of cardiac death, target-vessel myocardial infarction, ischemia-driven target vessel revascularization, or hospitalization for unstable or progressive angina at two years.

Park S-J, Ahn J-M, Kang D-Y, et al. Preventive percutaneous coronary intervention versus optimal medical therapy alone for the treatment of vulnerable atherosclerotic coronary plaques (PREVENT): A multicentre, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2024; Apr 4. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(24)00413-6. [Online ahead of print].

A majority of acute coronary syndrome events result from plaque rupture involving previously stable coronary plaque. The identification of so-called vulnerable plaques has long represented a holy grail of sorts in cardiology, with the related question being what can be done about them. In the PREVENT trial, the investigators asked the following question: Can treatment of non-flow-limiting vulnerable plaques by coronary stenting reduce the risk of downstream events, compared with standard medical therapy?

Fifteen hospitals in South Korea, Japan, New Zealand, and Taiwan participated in this trial, which enrolled patients presenting with primarily stable angina. Any flow-limiting lesions were treated with stenting prior to randomization. Subsequently, all untreated lesions that were judged to not be responsible for the presenting clinical syndrome were assessed. Those that were blocked 50% or more by visual estimate but negative by fraction flow reserve (FFR) then were evaluated by a variety of intravascular imaging techniques: intravascular ultrasound (IVUS), optical coherance tomography (OCT), and near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS). Patients who were thought to have vulnerable plaques according to set criteria (plaques had to meet at least two of four entry criteria) then were randomized to stenting or to medical therapy. The primary outcome was a composite of cardiac death, target vessel myocardial infarction (MI) or ischemia-driven revascularization, or hospitalization for angina, as assessed at two years.

Ultimately, 5,627 patients were screened to identify 3,562 subjects with intermediate lesions, of which 1,608 (45%) met criteria for vulnerable plaque. Of these, 803 patients were enrolled in each arm. A majority of patients had a single qualifying lesion. The median age of enrollees was 65 years and 27% were women. Most patients had stable coronary disease, while 12% of patients had unstable angina and just 4% of patients had had a recent MI. The majority of plaques qualified by grayscale IVUS criteria of small minimal luminal area and plaque burden > 70%. Just more than one-quarter were identified as having large lipid-rich plaque by NIRS, and only a handful were identified as thin-cap fibroatheromas by OCT or by radiofrequency IVUS. Only 1% of patients in the control arm crossed over to receive preventive stenting, while 9% of stent-assigned patients received medical therapy alone.

At two years, a primary outcome event had occurred in only three patients in the preventive stenting group (0.4%), compared with 27 (3.4%) medical therapy patients. This was reported as an absolute risk difference of -3.0% (95% confidence interval, -4.4 to -1.8; P = 0.0003). Each component of the primary outcome favored preventive percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). Four patients in the preventive stenting group had procedure-related adverse events.

Examination of the Kaplan-Meier plots shows that most of the benefit of PCI occurred in the early months, and after that the curves appear parallel. Follow-up data were available out to as much as 7.9 years (median 4.3 years). Notably, while a risk difference remained at seven years, this no longer met statistical significance.

The authors reported that preventive stenting of non-flow-limiting, intravascular imaging-defined vulnerable plaques reduced major cardiac events compared with medical therapy alone. They further stated that these results “support consideration to expand indications for PCI to include non-flow-limiting, high-risk vulnerable plaques.”

COMMENTARY

PREVENT represents a significant achievement in clinical investigation, testing a disruptive concept and coming out with a significant result. Previous positive studies supporting the concept of preventive PCI have focused not on vulnerable plaque, per se, but rather on the vulnerable patient. Multiple trials (COMPLETE, PRAMI, CvLPRIT, DANAMI-3, COMPARE-ACUTE) have looked at the question of revascularization of non-culprit lesions in patients presenting with ST-elevation MI (STEMI) (these are some of the highest risk patients for recurrent events) and have shown a reduction in hard endpoints, including cardiac death and MI.

PREVENT focused instead on a stable coronary disease population, and, as expected, the downstream event rate was much lower than what is seen in patients post-STEMI. In fact, although the trialists predicted a two-year event rate of 12%, the actual rate in the medical therapy arm was only 3.4%. One result of this is that the entire trial result hinges on a difference of only 24 events between groups. This relatively fragile result should not be sufficient to change general practice.

The positive results in the face of low event rates speak to the remarkable safety of PCI in the interventional arm. Notably, the trial was designed to use absorbable stents, and approximately one-third of patients received these devices before those stents were withdrawn from the market for higher event rates compared with metallic stents.

A major adverse cardiac event rate of only 0.4% is incredibly low, besting almost any modern trial of coronary stenting. Part of the explanation for this, in addition to the skill of the operators and the targeting of “easy” non-obstructive plaque, was the use of intravascular imaging (IVI) in essentially all cases. IVI is used in a small minority of coronary interventions in the United States (although its use is much higher in other parts of the world where payment structures help support it), despite mounting evidence that its use improves hard outcomes. So, in part, PREVENT is an additional advertisement for the efficacy of IVI when used routinely to improve safety in PCI.

Is a stent the best way to treat vulnerable plaque, when the expected event rate is so low? Dual antiplatelet therapy use was of course much higher in the PCI arm, potentially accounting for some of the event difference. Patients in the medical arm were well managed, but no additive therapies (e.g., PCSK9 inhibitors) were used in a majority of patients. While I suspect that some cardiologists may consider changing practice based on these results alone, the evidence remains too limited to affect guidelines. Fortunately, there are additional studies already in the works that one hopes will shed more light on this important area.