Bougie Use in Airway Management in the Critically Ill

December 1, 2022

Related Articles

-

Infectious Disease Updates

-

Noninferiority of Seven vs. 14 Days of Antibiotic Therapy for Bloodstream Infections

-

Parvovirus and Increasing Danger in Pregnancy and Sickle Cell Disease

-

Oseltamivir for Adults Hospitalized with Influenza: Earlier Is Better

-

Usefulness of Pyuria to Diagnose UTI in Children

By William Tyler Smith, MD, and Alexander Niven, MD

Dr. Smith is Pulmonary and Critical Care Fellow, Division of Pulmonary/Critical Care Medicine, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN. Dr. Niven is Consultant, Division of Pulmonary/Critical Care Medicine, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN.

Despite significant advances in our understanding of airway management and intubation of the critically ill, this common intensive care unit (ICU) procedure remains high-risk. Critically ill patients have a higher frequency of difficult airways, defined by the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) as a “situation in which anticipated or unanticipated difficulty or failure is experienced by a physician trained in anesthesia care.”1 This can be attributed to challenges with glottic visualization and shorter safe intubation times after induction because of limited cardiopulmonary reserve.1,2 Severe consequences, such as hypoxia (SpO2 < 80%) or hypotension (systolic blood pressure < 65 mmHg), have been reported to occur in as many as 34% of ICU intubations with standard care, in addition to cardiac arrest and even death.3 Although failures in planning, preparation, and teamwork have been identified as the most common reasons for emergent airway complications, efforts to standardize airway team protocols also have included the study of airway tools that may increase the safety of this procedure.4 The bougie (also referred to as a gum elastic bougie, endotracheal tube introducer, or intubating stylet) has been used as an adjunct in endotracheal intubation for more than 70 years and is among the procedure’s most studied tools. However, its role in initial emergent intubation attempts in critically ill patients remains hotly debated.

Macintosh first described bougie use in airway management in 1949.5 At that time, gum elastic bougies were commonly used to dilate urethral strictures. He described threading the bougie through the vocal cords under direct visualization, and then passing the endotracheal tube over this guide. The short length of the bougie allowed this introducer and the endotracheal tube to be passed together, with the bougie protruding only a few centimeters past the end of the tube. In the 1970s, Venn developed the Eschmann endotracheal tube introducer, which was longer, made of flexible plastic, and included a coude tip.6 The increased length of this new endotracheal tube introducer required modification and adoption of a Seldinger-like technique, where the bougie was appropriately located in the trachea with the endotracheal tube loaded over this device and advanced through the glottis.7

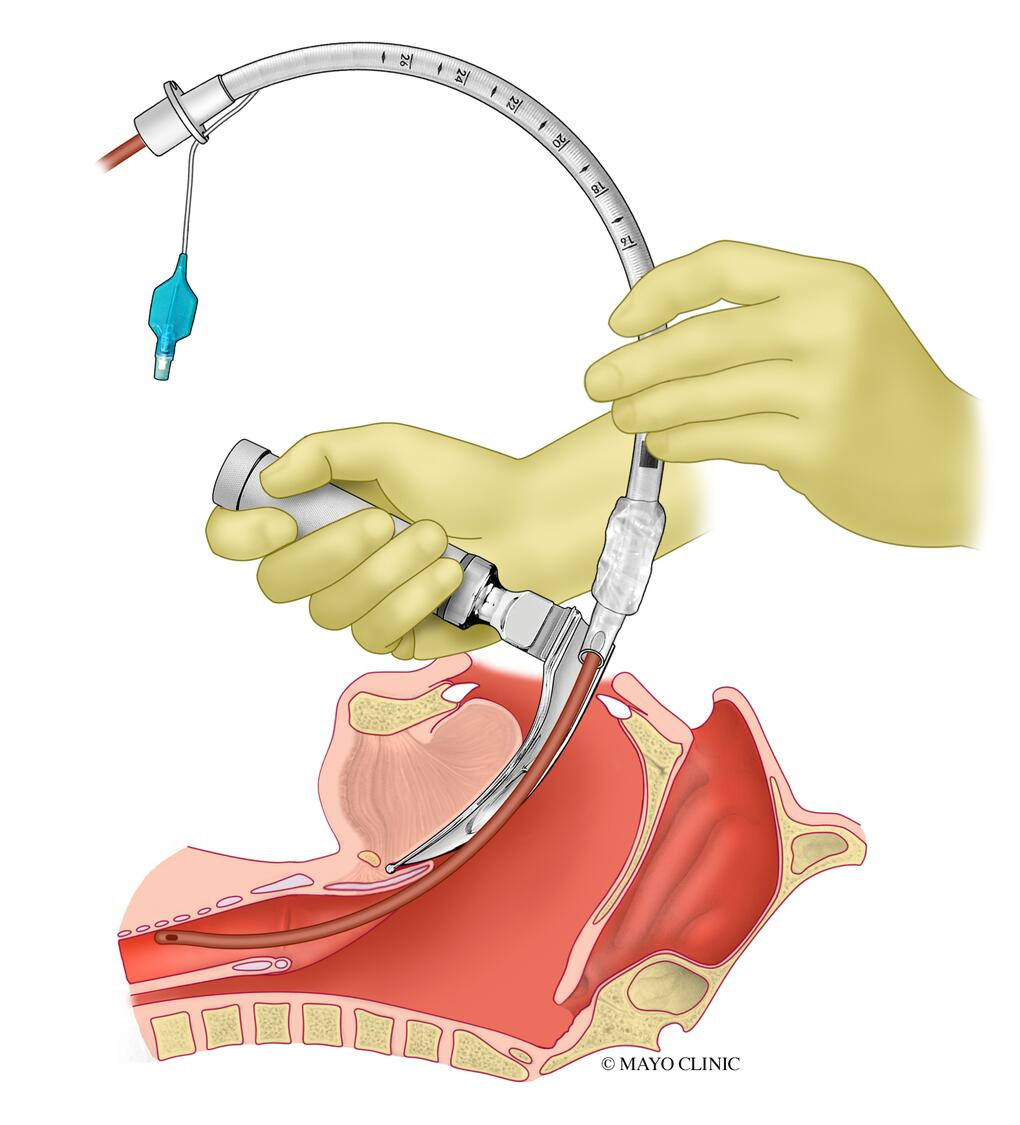

Manufacturing advances led to broader adoption of the bougie in practice using this Seldinger method. Using direct or video laryngoscopy, and after appropriate patient positioning, the epiglottis and glottis are identified. The bougie then is introduced through the mouth with the coude tip directed anteriorly and advanced under visualization, direct or indirect, into the trachea. (See Figure 1.) Tactile confirmatory tests for placement have been described when the vocal cords are poorly visualized, including the “click” and “hold up” signs. The “click” describes the feeling of the anteriorly directed coude tip traversing the cartilaginous tracheal rings and producing a vibration while it is advanced. The “hold up” sign occurs when the coude tip passes the carina and lodges in a distal airway, creating resistance to further advancement. An early study of 78 patients found the “hold up” sign was present in all tracheally intubated patients, at a mean depth of 31.9 cm (range 24 cm to 40 cm). The ability to advance the bougie past 40 cm without any resistance suggested esophageal intubation.8

Another commonly encountered obstacle during bougie-assisted intubation occurs when the endotracheal tube catches on an arytenoid cartilage or other adjacent structure. This problem typically can be addressed by withdrawing the endotracheal tube 2 cm and rotating it 90 degrees counterclockwise before readvancement.9 Although some authors have raised concerns about the risk of airway damage when excessive force is used, the use of the bougie has not been consistently linked to an increased risk of trauma.

Figure 1: Advancement of Endotracheal Tube Over Bougie in Typical Use |

|

Used with permission of Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research, all rights reserved. |

The bougie has been recommended as one of many alternate approaches to difficult airway management since the publication of the first ASA guidelines on this topic in 1993. A tracheal tube guide also was recommended as part of the portable storage unit for difficult airway management.10 Although subsequent updates have acknowledged observational studies that suggest that an intubating stylet, tube exchanger, or gum elastic bougie may increase intubation success and reduce adverse outcomes, recent guidelines state that current evidence remains insufficient to determine which airway adjunct is most effective after an initial failed intubation attempt, or the most effective order of alternate approaches.1,11

Use of the bougie during the initial intubation attempt has occurred primarily in the prehospital setting, but the Bougie Use in Emergency Airway Management (BEAM) study sparked considerable controversy regarding the potential use of this strategy in the critically ill.9 The BEAM trial was a large, single-center prospective study that randomized 757 consecutive patients in the emergency department requiring emergent orotracheal intubation to either use of a bougie or a traditional stylet during the first intubation attempt. To balance the number of patients with difficult airway characteristics, randomization was stratified to include equal numbers of patients with either obesity or cervical immobilization in each arm. Most patients enrolled presented to the emergency department with medical illnesses, with altered mental status the primary indication for airway management in nearly half of this population. There also was a significant population of trauma patients (17% and 16% in the bougie vs. traditional stylet groups, respectively). Half of the enrolled subjects had at least one difficult airway characteristic, and the majority received rapid sequence induction using a C-MAC videolaryngoscope with Macintosh blade (although the screen was never used in 52% of these intubations).

The authors found a significantly higher rate of first-pass success with bougie use compared to traditional stylet in both patients with (96% vs. 82%, respectively, P < 0.001) and without (99% vs. 92%, respectively, P < 0.001) difficult airway characteristics, with particular advantages noted in patients with cervical immobilization, obesity, and incomplete glottic visualization (Cormack-Lehane grades 2-4). Although there were significant differences in intubation times between the two groups, in patients with first-pass success the bougie group only had a median increase in procedure time of four seconds. Of the 56 unsuccessful first-pass attempts, 49 were subsequently intubated successfully with a bougie. It is important to note that first-pass bougie use was routine practice at this institution prior to the trial, and the extremely high first-pass success rates in comparison to other reported outcomes in the critically ill suggest both considerable training and a well-organized airway management program.12,13

The Bougie or Stylet in Patients Undergoing Intubation Emergently (BOUGIE) study was a large, multicenter, pragmatic prospective randomized trial designed to determine if the BEAM results could be replicated in seven emergency departments and eight ICUs at 11 hospitals across the United States.12 Patients were eligible for enrollment and randomization if they were undergoing tracheal intubation with sedation and a nonhyperangulated (Macintosh or Miller) blade. All operators received structured education regarding best practices in the use of the bougie and stylet during intubation using a standardized educational video and in-person training prior to study initiation. A total of 1,102 patients were enrolled, with similar indications for intubation and frequency of difficult airway characteristics compared to the BEAM trial. A videolaryngoscope was used in 74% of these procedures.

In contrast to the BEAM results, the BOUGIE trial found no significant difference in the rate of first-pass success between use of bougie vs. stylet (80.4% vs. 83.0%), even at higher Cormack-Lehane grades. There was no significant difference in success between groups in patients with at least one difficult airway characteristic or when stratified by operator experience. The median time from induction to intubation was 12 seconds longer in patients randomized to bougie use, in keeping with the original descriptions of this technique.13 These findings suggest that, when studied in a wider range of settings and with users less familiar with this technique, use of the bougie does not significantly increase the chance of first-pass intubation success.

However, the rise and fall of the bougie as a primary intubation strategy in the critically ill should not dismiss its importance in ICU airway management. Bougie use is routinely recommended as an airway management strategy in many challenging patient populations, including patients requiring cervical spine immobilization, patients with poor laryngeal views, and patients with prior failed intubation attempts.1,2,14,15 It also has been shown to be the rescue strategy of choice in initial failed emergent intubation attempts across multiple studies and practice recommendations.9,16 More recently, flexible and steerable bougie tips have been developed with the ability to alter the angle in one plane which, combined with rotation of the device, allows significant mobility. The flexible tip also is thought to reduce the risk of the coude tip impeding endotracheal tube advancement. Difficulties passing the endotracheal tube over the bougie have been noted less frequently with these devices, but data regarding increased success and intubation time are conflicting.17,18

The BEAM and BOUGIE trials also teach us several other important lessons about airway management in the critically ill. The remarkable first-pass success rates in the BEAM trial demonstrate that a rigorous, standardized airway management strategy deployed by a highly trained team can improve the success and safety of this procedure in the critically ill. The lower rates seen in the BOUGIE trial and other ICU airway studies highlight a continued practice gap that must be urgently addressed by our subspecialty. It is important to highlight that the rate of clinically significant hypoxemia (SpO2 < 80%) ranged between 8% and 14% in both the BEAM and BOUGIE trials, with 14% and 18.6% of patients randomized to bougie and stylet, respectively, in the latter trial experiencing cardiovascular collapse or arrest. These sobering data highlight the important work that still must be done to reduce the frequency of these serious complications and their sequelae, which clearly will not be solved solely by the increasing number of airway management tools available for primary and rescue intubation attempts.

Although data currently are insufficient to recommend routine bougie use during the initial intubation attempt in all settings, the high rate of success in BEAM study underlines the importance of training and clinical experience with this tool, which has been well-studied and widely accepted as an adjunct in difficult airways and as a rescue strategy in failed intubation attempts. Overall, the bougie is a low-cost and effective tool that deserves a place in the standardized ICU airway supply cart, and its use remains an important skill for the practicing intensivist performing endotracheal intubation.

REFERENCES

- Apfelbaum JL, Hagberg CA, Connis RT, et al. 2022 American Society of Anesthesiologists Practice Guidelines for Management of the Difficult Airway. Anesthesiology 2022;136:31-81.

- Higgs A, McGrath BA, Goddard C, et al. Guidelines for the management of tracheal intubation in critically ill adults. Br J Anaesth 2018;120:323-352.

- Jaber S, Jung B, Corne P, et al. An intervention to decrease complications related to endotracheal intubation in the intensive care unit: A prospective, multiple-center study. Intensive Care Med 2010;36:248-255.

- Cook TM, Woodall N, Harper J, Benger J; Fourth National Audit Project. Major complications of airway management in the UK: Results of the Fourth National Audit Project of the Royal College of Anaesthetists and the Difficult Airway Society. Part 2: Intensive care and emergency departments. Br J Anaesth 2011;106:632-642.

- Macintosch R. An aid to oral intubation. Br Med J 1949;1:28.

- Venn PH. The gum elastic bougie. Anaesthesia 1993;48:274-275.

- Henderson JJ. Development of the ‘gum-elastic bougie.’ Anaesthesia 2003;58:103-104.

- Kidd JF, Dyson A, Latto IP. Successful difficult intubation. Use of the gum elastic bougie. Anaesthesia 1988;43:437-438.

- Driver BE, Prekker ME, Klein LR, et al. Effect of use of a bougie vs endotracheal tube and stylet on first-attempt intubation success among patients with difficult airways undergoing emergency intubation: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2018;319:2179-2189.

- [No authors listed]. Practice guidelines for management of the difficult airway: A report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Management of the Difficult Airway. Anesthesiology 1993;78:597-602.

- American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Management of the Difficult Airway. Practice guidelines for management of the difficult airway: An updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Management of the Difficult Airway. Anesthesiology 2003;98:1269-1277.

- Driver BE, Semler MW, Self WH, et al. Effect of use of a bougie vs endotracheal tube with stylet on successful intubation on the first attempt among critically ill patients undergoing tracheal intubation: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2021;326:2488-2497.

- Nolan JP, Wilson ME. An evaluation of the gum elastic bougie. Intubation times and incidence of sore throat. Anaesthesia 1992;47:878-881.

- Nolan JP, Wilson ME. Orotracheal intubation in patients with potential cervical spine injuries. An indication for the gum elastic bougie. Anaesthesia 1993;48:630-633.

- Cook TM. A new practical classification of laryngeal view. Anaesthesia 2000;55:274-279.

- Murphy MF, Hung OR, Law JA. Tracheal intubation: Tricks of the trade. Emerg Med Clin North Am 2008;26:1001-1014, x.

- Oxenham O, Pairaudeau C, Moody T, Mendonca C. Standard and flexible tip bougie for tracheal intubation using a non-channelled hyperangulated videolaryngoscope: A randomised comparison. Anaesthesia 2022;77:1368-1375.

- Ruetzler K, Smereka J, Abelairas-Gomez C, et al. Comparison of the new flexible tip bougie catheter and standard bougie stylet for tracheal intubation by anesthesiologists in different difficult airway scenarios: A randomized crossover trial. BMC Anesthesiol 2020;20:90.

Despite significant advances in our understanding of airway management and intubation of the critically ill, this common intensive care unit (ICU) procedure remains high-risk.

Subscribe Now for Access

You have reached your article limit for the month. We hope you found our articles both enjoyable and insightful. For information on new subscriptions, product trials, alternative billing arrangements or group and site discounts please call 800-688-2421. We look forward to having you as a long-term member of the Relias Media community.