The Difficult Chronic Pain Patient: A Case of Borderline Personality Disorder?

The Difficult Chronic Pain Patient: A Case of Borderline Personality Disorder?

Authors: Randy A. Sansone, MD, Professor, Departments of Psychiatry and Internal Medicine, Wright State University School of Medicine, Dayton, Ohio; Director, Psychiatry Education, Kettering Medical Center, Kettering, OH

Lori A. Sansone, MD, Civilian Family Medicine Physician and Medical Director of the Family Health Clinic, Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, Dayton, OH

Peer Reviewer: Sarah L. Tragesser, PhD, Associate Professor of Psychology, Washington State University, Richland, WA

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy or position of the U.S. Air Force, Department of Defense, or U.S. Government.

Borderline personality disorder (BPD) is a striking personality dysfunction characterized by inherent difficulties with self-regulation as well as chronic self-destructive behavior. In patients with this disorder, the pain experience is seemingly paradoxical. During acute self-destructive acts, up to 80% of individuals with BPD describe attenuated responses to pain (i.e., high tolerance of pain). However, with pain that is chronic and endogenous, a number of patients with this disorder over-experience or are intolerant to pain — in part perhaps because of their innate difficulties with the self-regulation of pain. BPD appears to be commonly comorbid with non-malignant chronic endogenous pain. The averaged prevalence rate of BPD in eight studies of patients with various types of chronic pain syndromes is 30% — a rate that is 4.5 times the prevalence rate for BPD encountered in the general population. Because of the self-regulation difficulties encountered in BPD, many of these individuals have an addictive nature, which potentially complicates the pharmacological management of pain. In addition, the overall management approach to patients with BPD and chronic endogenous pain should be conservative and closely monitored by the clinician. Overall, patients with this type of comorbidity are challenging to manage.

Introduction

According to the Institute of Medicine, pain is a significant public health concern in the United States.1 In support of this claim, the Institute reports that pain management costs society at least $560-$635 billion annually — an amount that if prorated would cost every individual in the United States approximately $2000. This amount includes the total cost of health care for pain management, which ranges between $261 to $300 billion, as well as lost work productivity (e.g., days of missed work, hours of lost work, lower wages), which ranges between $297-$336 billion.1

Given this costly financial backdrop, clinicians are keenly aware that pain and the management of pain are genuinely complex and controversial issues in today’s contemporary health care climate. This is, in part, because of: 1) the inherent subjective nature of pain; 2) the association of pain with a host of comorbid medical and psychiatric conditions; 3) the resistance of pain, at times, to respond to treatment; and 4) the risk-laden pharmacological treatment of pain, which often entails the prescription of controlled substances. In turn, controlled substances give rise to the accompanying concerns about patient addiction to, misuse of, and overdose with these medicines.

Given this thorny terrain, the presence and influence of comorbid psychopathology is of particular interest and an understandable cofounding factor in pain management. This may be particularly relevant with regard to the personality disorders, because of their longstanding nature and resistance to change. One especially challenging personality dysfunction in this regard is BPD. This particular personality disorder would be likely to demonstrate a higher-than-expected rate of comorbidity in non-malignant chronic pain syndromes because BPD is characterized by self-regulation deficits and excessive pain in some individuals may be the result of an inherent inability to self-regulate pain.

This article will summarize the relevant clinical characteristics of BPD as well as the features of this personality dysfunction that may account for its role in the experience of pain. It will review the peculiar and paradoxical clinical phenomena of either under-experiencing or over-experiencing pain among BPD patients, and will discuss the prevalence of BPD in populations of patients with various non-malignant chronic pain syndromes. Finally, the article will close with a brief summary of clinical suggestions for the management of patients with pain who also suffer from this comorbid personality dysfunction.

What is Borderline Personality Disorder?

A Description of BPD. BPD is designated as a personality dysfunction in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5), and is assigned to the Cluster B group of personality disorders.2 The Cluster B group of personality disorders consists of those personality dysfunctions whose features are characterized as dramatic, emotional, and erratic. This group includes BPD as well as histrionic, narcissistic, and antisocial personality disorders. Among the 11 personality disorders noted in the DSM-5, which includes personality disorder not otherwise specified, BPD is the most researched.

BPD is a seemingly unique personality dysfunction because of these individuals’ inherent difficulties with self-regulation (i.e., an inability to regulate core behaviors related to self-management). Because of these innate struggles with self-control, individuals with BPD tend to manifest various “addictive” behaviors, or behavioral symptoms characterized by excess, such as bulimia nervosa, binge eating disorder, obesity, alcohol/drug misuse, prescription medication misuse, excessive spending, and promiscuity. Self-regulation difficulties also may manifest as affective instability or emotional lability, which is viewed by some as a core feature of BPD. Furthermore, self-regulation difficulties may manifest in an inability to regulate the experience of non-malignant chronic endogenous pain. These self-regulation difficulties tend to be longstanding and often clinically persist throughout the individual’s lifetime.

In addition to self-regulation difficulties, individuals with BPD display chronic self-destructive behavior. These behaviors may be quite graphic and dramatic (e.g., cutting, scratching, burning oneself; pulling out hair; attempting suicide), particularly among patients with BPD in psychiatric settings. However, sometimes self-destructive behavior manifests as a somatically incapacitated lifestyle characterized by an inability to meet the demands of various life roles and disability — a common presentation in medical settings.

The Diagnosis of BPD. According to the DSM-5, BPD is characterized by nine clinical features; five are required for diagnosis.2 These features are: 1) frantic efforts to avoid abandonment; 2) a history of unstable and intense relationships with others; 3) identity disturbance; 4) impulsivity in at least two functional areas such as spending, sex, substance use, eating, or driving; 5) recurrent suicidal threats or behaviors as well as self-mutilation; 6) affective instability with marked reactivity of mood; 7) chronic feelings of emptiness; 8) inappropriate and intense anger or difficulty controlling anger; and 9) transient stress-induced paranoid ideation or severe dissociative symptoms. Because there are nine possible diagnostic features and only five are required for confirmation, there may be notable variation in symptom presentation from one patient with BPD to another.

The Epidemiology of BPD. In the general population, the prevalence of BPD is approximately 6%, with equal proportions among men and women.3 Rates of BPD may be higher in westernized societies, but the presence of multiple somatic symptoms (a potential feature of BPD) may have been overlooked in previous prevalence studies in nonwesternized societies, resulting in underdiagnosis.2 Symptoms typically begin to manifest in late adolescence, but may emerge later in early adulthood.2

The Etiology of BPD. The explicit etiology of BPD remains unknown. However, the proposed cause of this disorder is currently described as multi-determined (i.e., the interaction of genetics with a number of environmental risk factors), which is typical fare for all of the psychiatric disorders. However, repetitive trauma in childhood appears to be a significant historic finding in the majority of cases (e.g., repetitive emotional, sexual, and/or physical abuse during the formative years), suggesting that this etiological factor harbors some significance in the development of BPD.4

Symptom Expression in BPD: Psychological Symptoms vs Somatic Symptoms. With regard to the expression of clinical symptoms, patients with BPD appear to display either a predominance of psychological symptoms or a predominance of somatic symptoms. When psychological symptoms are predominant, the patient tends to seek out psychological and/or psychiatric services in outpatient and inpatient mental health settings. Psychological symptoms typically manifest as relationship difficulties, rage reactions, chronic depression, self-mutilation, alcohol/drug misuse, and suicide attempts.

When somatic symptoms are predominant, the patient tends to seek out primary care services in family practice and internal medicine outpatient settings as well as emergent services in urgent care and emergency department settings. In these circumstances, patients with BPD often display numerous somatic symptoms.5 These somatic symptoms may be associated with any organ or system, but rather than location, it is the number of symptoms that seems to be most suggestive of BPD (i.e., somatic preoccupation). The diffuse somatic symptoms encountered in this subgroup of patients with BPD often lack explicit diagnostic confirmation through laboratory or other testing. In addition, a fair portion of these individuals will be diagnosed with indistinct and vague syndromes such as fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome, attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder, and irritable bowel syndrome. Many of these individuals have been traditionally described by primary care clinicians as “difficult patients.”6

In either psychological or medical settings, individuals with BPD will typically harbor numerous symptoms that tend to culminate in multiple contacts with the office, multiple appointments, multiple diagnoses, multiple laboratory studies, multiple exposures to medications, multiple allergies, and multiple referrals to specialists.5 Overall, the medical history of individuals with BPD frequently reveals an unexplainable overutilization of health care resources.

The Pain Experience in Patients with BPD

The empirical literature on the pain experience in patients with BPD consists of two distinct veins of research. In the first and earliest vein of research, investigators examined the clinical observation that individuals with BPD appear to have high tolerances to pain, which was particularly evident during acute acts of intentional self-injury (e.g., self-cutting, self-burning).7,8

Studies of High Tolerance to Pain in BPD. Studies on high pain tolerance in BPD began to unfold in the early 1990s. Initially, these studies examined pain insensitivity in relationship to associated psychological features, solely through psychological assessments.9-11 Explicitly, the research question seemed to be, “What is the psychological configuration of patients with BPD who exhibit high pain tolerance?” Despite small sample sizes and the subjective nature of the psychological assessments, findings suggested that in comparison to controls, individuals with BPD who reported being highly tolerant to pain during acute acts of self-mutilation (e.g., self-cutting) also exhibited higher levels of depression, anxiety, and dissociation.9-11

Shortly thereafter, researchers began to go beyond examining psychological associations with pain tolerance to actually confirming pain tolerance. To do so, they examined various purportedly pain-tolerant samples of patients with BPD using experiments that entailed actual physical exposure to noxious painful stimuli. Initially, these stimuli consisted of thermal tests using heat or cold probes.12-17 However, the experimental stimuli eventually broadened out to include exposure to tourniquets,18 mechanical pressure,19 capsaicin,19 laser radiant heat impulses,20 and electrical stimuli.21 In keeping with the proclamations of these individuals, the data from these empirical studies seemed to confirm that a number of participants with BPD experience attenuated responses to pain. As a result of these findings, investigators estimated that an attenuated pain response may occur in up 80% of individuals diagnosed with BPD.15,18

Although the findings of the preceding studies with noxious stimuli affirmed clinical impressions, the potential limitations of their methodologies are noteworthy. These potential limitations include: 1) the reporting of subjective experiences by participants, 2) the subjective construct of most of the assessments, 3) and the willingness or not of participants to actually report pain.22

In contemporary times, investigators have re-examined the issue of pain tolerance in individuals with BPD using functional magnetic resonance imaging.23-26 Although testing paradigms have varied somewhat (e.g., most have used thermal stimuli, but one study utilized imaginal stimuli), findings have been somewhat consistent in demonstrating differences between participants with BPD and controls.

Through these various investigations, researchers seemed to be confirming that patients with BPD do indeed exhibit a high tolerance for pain. Such a finding understandably resulted in speculation about why pain tolerance might occur among patients with BPD. McCown and colleagues proposed the theory that stress-induced analgesia might occur immediately before the act of self-injury and could account for the observed insensitivity to pain.27 Russ and colleagues suggested that the individual with BPD may be psychologically reinterpreting the experience of pain — a process that might be mediated by dissociation.10 Kemperman and colleagues proposed that there might be inherent neurosensory abnormalities among individuals with BPD,13 including the possibility of underlying attitudinal and/or psychological abnormalities.11 Russ and colleagues posited the release of endogenous opioids at the time of self-injury, thereby blocking the experience of pain and possibly reinforcing the likelihood of future self-harm behavior.12 Finally, Kluetsch and colleagues found significant alterations in the default mode network of the brain — a subsystem of brain connections that appears to be associated with one’s readiness to respond to environmental challenges.28 These latter findings may suggest a different cognitive and/or affective appraisal of pain.28 Such differences are supported by the findings of Cardenas-Morales and colleagues, who reported that participants with BPD demonstrate abnormalities in their affective responses to pain during repetitive peripheral magnetic stimulation.29

Realistically, while many of these hypotheses are intriguing to contemplate, they are challenging to empirically confirm. In addition, they may not be mutually exclusive. In other words, it may be that various types of reflexive psychophysiological processes occur at the moment of pain impact. Therefore, it is likely that the under-response to pain by individuals with BPD simultaneously entails multiple neuropsychological events.

To summarize, the preponderance of clinical and empirical evidence suggests that a number of individuals with BPD experience attenuated responses to pain during acute acts of self-mutilation. Are there other factors that might account for this? One possibility is the context of the pain. In a moment of crisis or in an experimental testing situation, the pain stimulus is self-inflicted or experimentally induced. It is acute, of short duration, and under one’s personal control (even in a clinical study, the subject may elect to withdraw at any time). What about the ability of patients with BPD to tolerate non-malignant chronic endogenous pain?

Studies of Low Tolerance to Pain in BPD. The second vein of empirical research in this area relates to studies of non-malignant chronic endogenous pain among individuals with BPD. In contrast to the findings with acute pain, clinical observations and a number of empirical studies seem to indicate that individuals with BPD appear to over-experience non-malignant chronic endogenous pain. From a clinical perspective, Harper summarized this observation by stating, “it [is] particularly difficult for... [the borderline patient] ...to endure prolonged acute pain” (p. 196); “the borderline patient’s tolerance of discomfort will typically be of shorter duration than other individuals” (p. 197).30

In confirming the preceding clinical impression, there are three studies to date that provide some insight into the relationship between BPD and non-malignant chronic endogenous pain. All three studies have entailed controls.31-33 In a 2010 study, Tragesser and colleagues examined relationships between BPD and pain ratings among 777 participants.31 Compared to those participants without BPD, participants with BPD reported a greater severity of pain as well as higher levels of minimum and maximum pain during the past month. In another 2010 study, Sansone and colleagues examined an internal medicine outpatient sample of 80 patients, using three measures for BPD diagnosis and visual analog scales to assess current pain and pain over the past 12 months.32 As hypothesized, compared to non-BPD participants, pain ratings were statistically significantly higher in the cohort with BPD at both time points. Using a different approach in a 2004 study, Frankenburg and Zanarini compared 200 patients with BPD symptoms in remission to 64 actively ill patients with BPD.33 The researchers found that remitted patients (i.e., patients with fewer BPD symptoms) were less likely to report pain or the sustained use of pain medications — an indirect but meaningful assessment of pain coping. Despite the subjective self-reporting of pain in these studies, findings consistently confirm that non-malignant chronic endogenous pain is less tolerated by individuals with BPD when compared to fellow non-BPD patients.

There may be a number of explanations for the observed overendorsement of chronic endogenous pain by patients with BPD. Perhaps the psychological process of elaborate dramatization is at play (i.e., a defining characteristic of the Cluster B disorders) and intensifies the individual’s experience and expression of pain. Likewise, perhaps the fundamental psychodynamic issue of impaired self-regulation partially explains these findings — i.e., that there is an inherent inability of individuals with BPD to effectively self-regulate pain. Additionally, due to the commonplace finding of maltreatment in childhood, perhaps pain sensitivity is accentuated through trauma psychodynamics. To further explain this possibility, trauma is known to result in posttraumatic stress disorder — a disorder characterized by hypervigilance.2 Hypervigilance is traditionally conceptualized as an intense exterior focus — being hypervigilant with regard to the environment. However, hypervigilance also can apply to the internal environment, with excessive self-scrutiny of and over-attention to internal sensations.5

In addition to the preceding explanations, a number of enticing secondary gains also may contribute to the over-experiencing of pain in patients with BPD. For example, from an interpersonal perspective, patients with pain complaints may wish to garner caring responses from others, particularly health care professionals. From a socioeconomic perspective, unrelenting pain may be a means of establishing and maintaining a disabled but financially secure status (i.e., a self-defeating lifestyle). Finally, pain complaints may function as a vehicle for procuring controlled substances — to dull the intrusive flashbacks of trauma, to misuse for recreation, or even to sell. Because of these varying possibilities, it is likely that the pain experience among individuals with BPD functions in various intrapsychic and interpersonal ways.

The Pain Paradox in BPD. How can individuals with BPD be simultaneously insensitive to pain and over-sensitive to pain? Part of the answer seems to reside in the context of the pain itself. Specifically, pain that is self-inflicted, of short duration, and directly under the individual’s personal control may be exceptionally well tolerated. This scenario seems to lend itself to the under-experiencing of pain or pain tolerance. However, pain that is chronic and endogenous, and/or not under individual’s control, may be poorly tolerated. This scenario seems to lend itself to the over-experiencing of pain or pain intolerance. To restate this proposal, because the two types of pain emerge in completely different contexts, there appear to be two distinctly different responses by individuals with BPD.

The Prevalence of BPD in Pain Populations

The third vein of research in this area consists of studies that have examined the prevalence of BPD among various populations of pain patients. These studies began to emerge in the mid-1990s.

The Studies. In the first study, Gatchel and colleagues examined a sample of 152 tertiary-care patients in the United States who suffered from chronic low back pain and disability.34 In this study, researchers utilized a structured interview for the diagnosis of BPD (structured interviews are regarded as the benchmark for BPD diagnosis in research settings). Investigators determined that 26.9% of participants had BPD.

Sansone and colleagues examined 17 primary care patients in the United States with various chronic pain complaints.35 In this study, researchers used two self-report measures and a semi-structured interview for the diagnosis of BPD (i.e., a rigorous diagnostic approach). According to these three study measures, 47.1% (self-report measure), 29.4% (self-report measure), and 47.1% (semi-structured interview) of participants met the criteria for BPD. Despite the small sample size, the percentages of affected patients were surprisingly high.

In a study of 150 tertiary care patients in the United States that consisted of two cohorts with chronic pain, Manchikanti and colleagues used psychological testing to ascertain BPD status.36 In these two samples of pain patients, 10% and 12% met the criteria for BPD.

Workman and colleagues examined 26 patients in the United States who were referred to a physical therapy-based pain management program.37 Using a self-report measure for BPD, investigators confirmed a prevalence rate of 31%.

In a study of 1323 tertiary care patients in the United States with chronic disabling occupational spinal disorders, Dersh and colleagues used a semi-structured interview for the assessment of BPD.38 (Again, interviews are purported to be the best diagnostic tools in personality disorder research.) In this large sample, 27.9% of participants met the criteria for BPD.

In a community sample of 1208 individuals in the United States, Braden and Sullivan examined rates of BPD using a screening questionnaire.39 In this sample, 27.4% of participants met the criteria for BPD.

In a sample of 117 tertiary care patients in the United States being seen by a pain management specialist, Sansone and colleagues used two self-report measures for the diagnosis of BPD.40 In this study, rates for BPD were 9.4% and 14.5%, according to each study measure.

Finally, in a German study of 48 tertiary care patients with various chronic pain symptoms, Fischer-Kern and colleagues used a semi-structured interview for BPD diagnosis.41 In this sample, 58% of participants met the criteria for BPD. For easy comparison, these data are summarized and presented in Table 1.

Table 1: Studies Examining the Prevalence of Borderline Personality Disorder in Various Samples of Patients with Pain

A Summary of the Existing Data. In summarizing these data, a total of eight studies have been published to date, with the first appearing in 1994. Most of these studies have consisted of patient samples residing in the United States. Study samples have been diverse and included participants from community, primary care, and tertiary care settings. Sample sizes have varied from 17 to 1323 participants, with the number of participants in all eight studies totaling 3041. The range of reported percentages for the prevalence of BPD is between 9% and 58%.

In analyzing these data, one simple approach is to average the percentages of BPD in the various studies. To account for all findings, if a given study used three assessment measures, then each percentage would be included in the total tally. Using this approach for all reported percentages, the averaged prevalence rate of BPD in these collective studies is 30.0%. This percentage seems credible given that it closely reflects the percentage reported by Dersh and colleagues.38 Recall that the study by Dersh et al represents the largest number of chronic pain patients to date (n = 1323). Using a semi-structured interview for diagnosis, considered the benchmark for personality disorder diagnosis, Dersh et al found a prevalence rate for BPD of 27.9%. This percentage is close to the averaged percentage we calculated. To reiterate, the findings from this review suggest that approximately 30% of chronic pain patients suffer from comorbid BPD.

Clinical Management of the Patient with Chronic Pain and Comorbid BPD

The Clinical Assessment of BPD. Given the high rates of BPD in patients with chronic pain syndromes, we advise clinicians to screen every chronic pain patient for this personality dysfunction. While the DSM-5 criteria are the preferred means of diagnosis, in non-mental health settings, these criteria can be challenging to use. First, the criteria are difficult to remember and some primary care clinics may not have a copy of the DSM-5. Second, some of the criteria are difficult to pose as questions to patients (e.g., frantic efforts to avoid abandonment, identity disturbances). Third, interpreting the patient’s response to questions can be challenging (i.e., is it a genuine endorsement of the item or not?). So while we enthusiastically endorse the DSM-5 criteria for BPD, they are sometimes challenging to operationalize in medical settings.

As alternatives to DSM diagnosis, there are a number of self-report measures for BPD. As a caveat, these measures tend to be over-inclusive and may generate false positives. Therefore, these measures are conceptualized as detecting borderline personality symptomatology, rather than confirming the disorder itself. Three self-report measures are well-known in the literature. The first is the BPD scale of the Personality Diagnostic Questionnaire-4 (PDQ-4), which is essentially a self-report version of the DSM criteria for BPD.42 This one-page, nine-item, true/false inventory queries respondents about how they have tended to feel, think, and act “over the past several years.” The criteria are very psychological in nature and include items such as, “I’ll go to extremes to prevent those who I love from ever leaving me,” “I feel that my life is dull and meaningless,” and “I often wonder who I really am.” A score on the PDQ-4 of 5 or higher is indicative of borderline personality symptomatology.

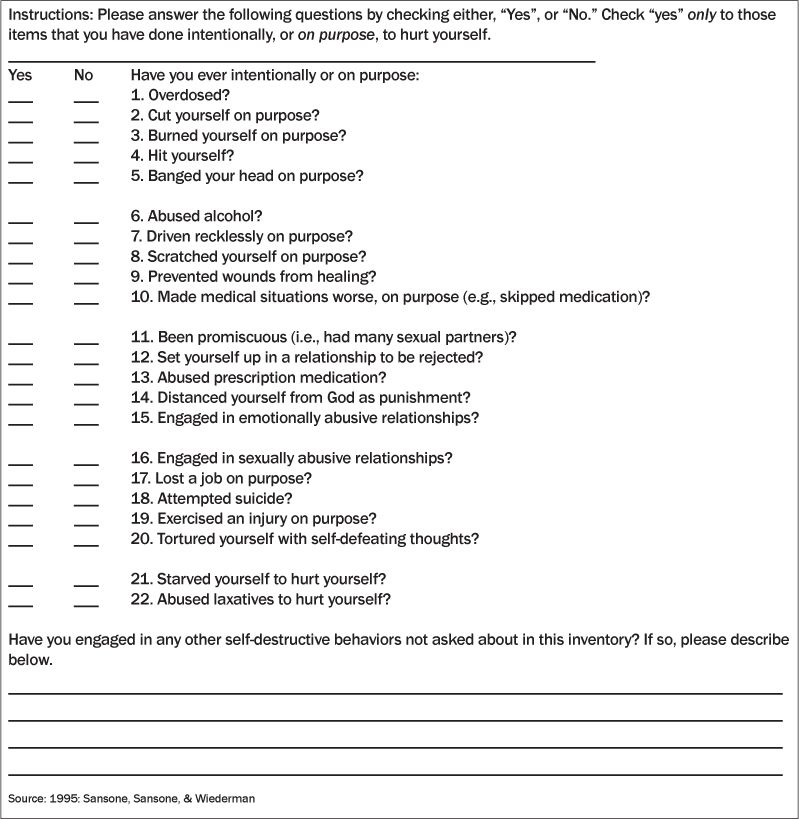

A second self-report measure for the assessment of BPD is the Self-Harm Inventory (SHI).43 The SHI is a one-page, 22-item, yes/no inventory that assesses self-harm behavior over the respondent’s lifetime. Items are preceded by the statement, “Have you ever intentionally, or on purpose, ....” Rather than being psychologically oriented, the individual SHI items are behaviorally oriented. For example, items include, “abused alcohol,” “driven recklessly on purpose,” “scratched yourself on purpose,” and “made medical situations worse, on purpose.” The SHI total score is a simple sum of “yes” responses, and a total score of 5 or higher is suggestive of borderline personality symptomatology. The SHI is displayed in Table 2 and may be reproduced for clinical use without charge.

Table 2: The Self-Harm Inventory

A third self-report measure for the assessment of BPD is the McLean Screening Inventory for Borderline Personality Disorder (MSI-BPD).44 This one-page, 10-item, yes/no inventory assesses a number of psychological features of BPD. Items are preceded by the stem, “During the past year,” and include, “Have you been extremely moody?” “Have you often been distrustful of other people?” and “Have you chronically felt empty?” The diagnostic cutoff score is 7. A potential hurdle in using the MSI-BPD is cost, as there is a fee for usage. As of this writing, a packet of 20 inventories is around $50 (Jones & Bartlett Learning).

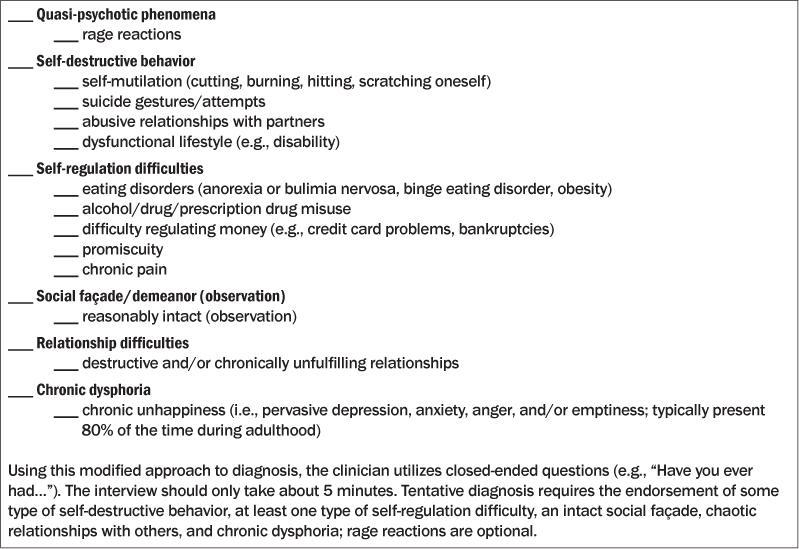

As an alternative to DSM-5 diagnosis and self-report measures, clinicians may briefly inquire about BPD symptoms using the core criteria contained in another assessment, the Diagnostic Interview for Borderlines (See Table 3).45 These criteria were originally developed within the context of a semi-structured interview. Using an abbreviated format, these criteria can be catalogued under six content areas and inquired about by asking, “Have you ever....” To meet the criteria for BPD, respondents need to show evidence of chronic self-destructive behavior, longstanding self-regulation difficulties, an intact superficial demeanor, longitudinal relationship difficulties, and chronic feelings of unhappiness. (The criterion for quasi-psychotic phenomena appears to be less essential to diagnosis, but clinically noteworthy.) These six items, and their accompanying sub-criteria, are presented in Table 3 in checklist fashion for ease-of-use in the clinical setting.

Table 3: Clinical Queries for Borderline Personality Disorder Based on the Diagnostic Interview for Borderlines45

The Importance of Accurately Diagnosing BPD. It is important to accurately diagnose BPD, and any of the preceding approaches can yield a reasonably accurate diagnosis of this disorder. Why such diagnostic caution? Because of the potential stigma associated with the diagnosis of BPD. Clinicians should always use some systematic process for diagnosis rather than an impressionistic approach or hunch, particularly before documenting the diagnosis of BPD in the medical record. Once confirmed, this diagnosis generally guides the clinician in the selection of a treatment course.

A Suggested Treatment Approach to Chronic Pain in Patients with BPD. The diagnosis of BPD somewhat modifies the treatment approach to patients with non-malignant chronic endogenous pain. First, given that patients with chronic pain and comorbid BPD appear to have exaggerated pain responses, the clinician bears the burden of factoring this phenomenon into the determination of the patient’s actual level of pain.

Second, for bona fide pain syndromes, a reasonable philosophy to establish at the outset of treatment with the patient is the following: We will attempt to improve your pain symptoms, but we are not likely to totally eradicate them. In other words, the patient should be informed at the outset of the clinician’s explicit and realistic treatment goals. Hopefully, the patient will support these goals.

Third, subsequent medical management should err on the conservative side (i.e., do no harm to the patient). For example, after consideration of low-risk interventions (e.g., physical therapy, lifestyle changes, site injections), the clinician is advised to cautiously approach the use of pain medications, beginning with modest agents at the outset (e.g., acetaminophen, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents), then intermediate agents (e.g., gabapentin, pregabalin, duloxetine, amitriptyline), and finally high-risk agents (e.g., tramadol, narcotic analgesics). Because of the potential for self-destructive behavior among patients with BPD, the use of medications that are high-risk in overdose may not be feasible for some patients (e.g., amitriptyline).

Fourth, the clinician should always keep in mind that patients with BPD have inherent self-regulation difficulties. Because of this clinical feature, these individuals are prone to narcotic-analgesic misuse and addiction. In support of this impression, in two studies, one a compilation of multiple databases (n = 1039) and the other a consecutive sample of 419 internal medicine outpatients, researchers confirmed relationships between the self-reported misuse of prescription medications and borderline personality symptomatology.46,47 Available data also indicate associations between narcotic prescriptions and fatal overdoses, although the role of BPD remains unclear at this juncture.48-51 Therefore, prescriptions for controlled pain medications need to be monitored carefully by the clinician.

As for other suggestions, pain management contracts are useful (e.g., no other prescribers, obligatory urine drug screens, utilization of only one pharmacy) as well as consolidating care under a single clinician. This latter suggestion is akin to “one cook in the kitchen,” and will enable the overall care plan to remain focused and centered. In keeping with this philosophy, no major changes in medication should take place in the absence of the primary clinician (e.g., during vacations) unless there is a genuine emergency. Likewise, clinicians may want to periodically check their state’s automated prescription reporting system to determine whether the patient is obtaining prescription narcotics from other sources.

Finally, the clinician may consider a referral to a psychiatrist or other mental health professional. There are a number of evidence-based treatments for BPD, such as dialectical behavior therapy, mentalization-based therapy, schema-focused therapy, and transference-focused therapy.52 However, referral to mental health services may be resisted by some patients, particularly if they are entrenched in their physical symptoms. Furthermore, retention in psychotherapy treatment may be a potential limitation (approximately 25% of patients with BPD elope from treatment53). However, when patient referral to a mental health professional appears feasible, it may be negotiated with the intent to “deal with the accompanying stress” of chronic pain.

From a purely speculative position, eventually a cognitive-behavioral treatment program likely will be developed for these challenging patients. To maximize success, these programs will have to be delivered in the medical setting where the patient receives treatment, perhaps via DVD.

Outcome. Although the long-term treatment outcome of patients with chronic pain and comorbid BPD remains empirically unknown, the broader empirical literature in the area of BPD and comorbid major psychiatric disorders suggests that this personality dysfunction will have a negative impact on the patient’s overall prognosis.54 Generally, patients with pain and comorbid BPD will need to be carefully and chronically monitored by the clinician. They may also be less likely to experience the resolution of pain symptoms as well as more likely to seek disability.

Conclusions

Research indicates that individuals with BPD are both highly pain tolerant as well as highly pain intolerant, depending on the context of the pain. Explicitly, during acute self-injury events, pain tolerance tends to be high, whereas with non-malignant chronic endogenous pain, pain tolerance tends to be low. As for the prevalence of BPD among chronic pain patients, present data indicate that approximately 30% suffer from this personality dysfunction. In most cases, the presence of BPD will complicate the treatment course, especially because of the patient’s difficulties with self-regulation and chronic self-destructive behavior. When comorbid BPD is present in the patient with non-malignant chronic endogenous pain, we recommend an overall conservative approach to pain management with close monitoring of controlled medications by the clinician. Although outcome studies of patients with pain and BPD are generally lacking, the clinician might anticipate a chronic course without full resolution of pain symptoms. Overall, these patients tend to be very challenging to manage. Primary care physicians are advised to use their knowledge of this disorder to select the tools presented here that work the best in their patients and in their practice.

References

1. National Research Council. Relieving Pain in America: A Blueprint for Transforming Prevention, Care, Education, and Research. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2011.

2. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, Inc.; 2013.

3. Grant BF, et al. Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV borderline personality disorder: Results from the Wave 2 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Clin Psychiatry 2008;69:533-545.

4. Sansone RA, Sansone LA. Borderline personality disorder: The enigma. Prim Care Rep 2000;6:219-226.

5. Sansone RA, Sansone LA. Borderline Personality in the Medical Setting. Unmasking and Managing the Difficult Patient. New York: Nova Science Publishers; 2007.

6. Sansone RA, Sansone LA. Personality disorders in the medical setting. In: Oldham JM, et al, eds. The American Psychiatric Publishing Textbook of Personality Disorders. 2nd Ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, Inc.: in press.

7. Lautenbacher S, Spernal J. Pain perception in psychiatric disorders. In: Lautenbacher S, Fillingim RB, eds. Pathophysiology of Pain Perception. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; 2004:163-183.

8. Jochims A, et al. Pain processing in patients with borderline personality disorder, fibromyalgia, and posttraumatic stress disorder. Schmerz 2006;20:140-150.

9. Russ MJ, et al. Subtypes of self-injurious patients with borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1993;150:1869-1871.

10. Russ MJ, et al. Pain and self-injury in borderline patients: Sensory decision theory, coping strategies, and locus of control. Psychiatry Res 1996;63:57-65.

11. Kemperman I, et al. Self-injurious behavior and mood regulation in borderline patients. J Pers Disord 1997;11:146-157.

12. Russ MJ, et al. Pain perception in self-injurious borderline patients: Naloxone effects. Biol Psychiatry 1994;35:207-209.

13. Kemperman I, et al. Pain assessment in self-injurious patients with borderline personality disorder using signal detection theory. Psychiatry Res 1997;70:175-183.

14. Russ MJ, et al. EEG theta activity and pain insensitivity in self-injurious borderline patients. Psychiatry Res 1999;89:201-214.

15. Schmahl C, et al. Differential nociceptive deficits in patients with borderline personality disorder and self-injurious behavior: Laser-evoked potentials, spatial discrimination of noxious stimuli, and pain ratings. Pain 2004;110: 470-479.

16. Russ MJ, et al. Pain perception in self-injurious patients with borderline personality disorder. Biol Psychiatry 1992;32:501-511.

17. Schmahl C, et al. Pain sensitivity is reduced in borderline personality disorder, but not in posttraumatic stress disorder and bulimia nervosa. World J Biol Psychiatry 2010;11:364-371.

18. Bohus M, et al. Pain perception during self-reported distress and calmness in patients with borderline personality disorder and self-mutilating behavior. Psychiatry Res 2000;95:251-260.

19. Magerl W, et al. Persistent antinociception through repeated self-injury in patients with borderline personality disorder. Pain 2012;153:575-584.

20. Ludascher P, et al. A cross-sectional investigation of discontinuation of self-injury and normalizing pain perception in patients with borderline personality disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2009;120:62-70.

21. Ludascher P, et al. Elevated pain thresholds correlate with dissociation and aversive arousal in patients with borderline personality disorder. Psychiatry Res 2007;149:291-296.

22. Lenzenweger MF, Pastore RE. On determining sensitivity to pain in borderline personality disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2007;64:747-748.

23. Niedtfeld I, et al. Affect regulation and pain in borderline personality disorder: A possible link to the understanding of self-injury. Biol Psychiatry 2010;68:383-391.

24. Ludascher P, et al. Pain sensitivity and neural processing during dissociative states in patients with borderline personality with and without comorbid posttraumatic stress disorder: A pilot study. J Psychiatry Neurosci 2010;35:177-184.

25. Kraus A, et al. Script-driven imagery of self-injurious behavior in patients with borderline personality disorder: A pilot fMRI study. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2010;121:41-51.

26. Schmahl C, et al. Neural correlates of antinociception in borderline personality disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2006;63:659-667.

27. McCown W, et al. Borderline personality disorder and laboratory-induced cold pressor pain: Evidence of stress-induced analgesia. J Psychopathol Behav Assess 1993;15:87-95.

28. Kleutsch RC, et al. Alterations in default mode network connectivity during pain processing in borderline personality disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2012;69:993-1002.

29. Cardenas-Morales L, et al. Exploring the affective component of pain perception during aversive stimulation in borderline personality disorder. Psychiatry Res 2011;186:458-460.

30. Harper RG. Borderline personality. In: Harper RG, ed. Personality-Guided Therapy in Behavioral Medicine. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2004:179-205.

31. Tragesser SL, et al. Borderline personality disorder features and pain: The mediating role of negative affect in a pain patient sample. Clin J Pain 2010;26:348-353.

32. Sansone RA, et al. The relationship between self-reported pain and borderline personality symptomatology among internal medicine outpatients. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry 2010;12:pii:PCC.09100933.

33. Frankenburg FR, Zanarini MC. The association between borderline personality disorder and chronic medical illnesses, poor health-related lifestyle choices, and costly forms of health care utilization. J Clin Psychiatry 2004;65:1660-1665.

34. Gatchel RJ, et al. Psychopathology and the rehabilitation of patients with chronic low back pain disability. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1994;75:666-670.

35. Sansone RA, et al. The prevalence of borderline personality among primary care patients with chronic pain. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2001;23:193-197.

36. Manchikanti L, et al. Do number of pain conditions influence emotional status? Pain Physician 2002;5:200-205.

37. Workman EA, et al. Comorbid psychiatric disorders and predictors of pain management program success in patients with chronic pain. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry 2002;4:137-140.

38. Dersh J, et al. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders in patients with chronic disabling occupational spinal disorders. Spine 2006;31:1156-1162.

39. Braden JB, Sullivan MD. Suicidal thoughts and behavior among adults with self-reported pain conditions in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. J Pain 2008;9:1106-1115.

40. Sansone RA, et al. Borderline personality among outpatients seen by a pain management specialist. Int J Psychiatry Med 2009;39:341-344.

41. Fischer-Kern M, et al. The relationship between personality organization and psychiatric classification in chronic pain patients. Psychopathology 2011;44:21-26.

42. Hyler SE. Personality Diagnostic Questionniare-4. New York; 1994.

43. Sansone RA, et al. The Self-Harm Inventory (SHI): Development of a scale for identifying self-destructive behaviors and borderline personality disorder. J Clin Psychol 1998;54:973-983.

44. Zanarini MC, et al. A screening measure for BPD: The McLean Screening Instrument for Borderline Personality Disorder (MSI-BPD). J Pers Disord 2003;17:568-573.

45. Kolb JE, Gunderson JG. Diagnosing borderline patients with a semi-structured interview. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1980;37:37-41.

46. Sansone RA, Wiederman MW. The abuse of prescription medications: Borderline personality patients in psychiatric versus non-psychiatric settings. Int J Psychiatry Med 2009;39:147-154.

47. Sansone RA, et al. The abuse of prescription medications: A relationship with borderline personality? J Opioid Manag 2010;6:159-160.

48. Wunsch MJ, et al. Opioid deaths in rural Virginia: A description of the high prevalence of accidental fatalities involving prescribed medications. Am J Addict 2009;18:5-14.

49. Paulozzi LJ, Xi Y. Recent changes in drug poisoning mortality in the United States by urban-rural status and by drug type. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2008;17:997-1005.

50. Shah NG, et al. Unintentional drug overdose death trends in New Mexico, USA, 1990-2005: Combinations of heroin, cocaine, prescription opioids and alcohol. Addiction 2008;103:126-136.

51. Piercefield E, et al. Increase in unintentional medication overdose deaths: Oklahoma, 1994-2006. Am J Prev Med 2010;39:357-363.

52. Sollberger D, Walter M. Psychotherapy of borderline personality disorder: Similarities and differences in evidence-based disorder-specific treatment approaches. Fortschr Neurol Psychiatr 2010;78:698-708.

53. Barnicot K, et al. Treatment completion in psychotherapy for borderline personality disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2011;123:327-338.

54. Bahorik AL, Eack SM. Examining the course and outcome of individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia and comorbid borderline personality disorder. Schizophr Res 2010;124:29-35.

Borderline personality disorder (BPD) is a striking personality dysfunction characterized by inherent difficulties with self-regulation as well as chronic self-destructive behavior. In patients with this disorder, the pain experience is seemingly paradoxical. During acute self-destructive acts, up to 80% of individuals with BPD describe attenuated responses to pain (i.e., high tolerance of pain).Subscribe Now for Access

You have reached your article limit for the month. We hope you found our articles both enjoyable and insightful. For information on new subscriptions, product trials, alternative billing arrangements or group and site discounts please call 800-688-2421. We look forward to having you as a long-term member of the Relias Media community.