Diet and Macular Degeneration: Eye-Opening Potential

By Susan T. Marcolina, MD, FACP. Dr. Marcolina is an internal medicine and geriatrics provider at Overake Medical Clinics in Bellevue, Washington; she reports no financial relationship to this field of study.

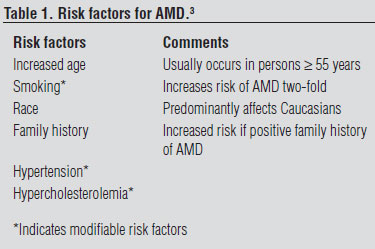

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is the leading cause of blindness in adults in the United States and western Europe. Approximately 26% of adults older than 65 have some form of AMD.1 It is a multifactorial, degenerative disease that affects the specialized retinal tissue responsible for the formation of sharp images in the central vision. Genetic susceptibility, age-related changes in retinal structure, and energy metabolism combined with cumulative environmental exposures, particularly to ultraviolet light, render the neurovascular retinal epithelium susceptible to oxidative damage.2 Although the etiology has not been fully elucidated, there are several risk factors outlined in Table 1.3

Table 1. Risk factors for AMD.3

AMD Pathophysiology

The disease is characterized by a non-exudative (dry) form and a more advanced exudative (wet) form. The non-exudative form begins with the accumulation of yellow, pleomorphic, extracellular deposits called drusen under the retinal pigment epithelium of the macula. These deposits initially do not cause visual loss, but as they become more numerous, enlarge to >125 micrometers, and become confluent, the retinal pigment epithelium becomes detached and atrophic, resulting in visual loss due to interference with photoreceptor functioning. Exudative MD, which develops in approximately 10% of patients, occurs when choroidal neovascularization penetrates the defects in retinal pigmented epithelium and leakage and/or hemorrhage from these vessels elevates the retina. This initiates an inflammatory cascade, resulting in fibrosis, scarring, and progressive visual loss. The exudative form accounts for 79%-90% of blindness from AMD.1 Although photodynamic therapy and pharmacologic interventions, such as intravitreal injection of anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) drugs, are available for neovascular AMD, they are costly, are limited in scope, have risk with administration (inflammation, increased intraocular pressure, and infection from intravitreous injections), and can also result in visual loss. There is currently no treatment for the dry form.4

With the anticipated growth of the aging population, the prevalence of this disease, and its disabling consequences, there is a requirement for less invasive and more cost-effective lifestyle strategies focused, first and foremost, upon primary disease prevention, as well as slowing disease progression with the goal of sight preservation. Interestingly, several dietary nutrients with antioxidant properties such as lutein, zeaxanthin, provitamin A carotenoids, vitamins E and C, and omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids are concentrated in the retina and thus may function to modulate both the exogenous and endogenous sources of oxidative stress and inflammation that may be responsible for the pathophysiology of AMD. Therefore, the possibility of using a dietary approach focusing on carotenoid intake, and long-chain omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (LCο3PUFAs), as well as supplemental zinc, to improve eye health, as well as general medical health, has been an important research focus over the past decade.

Retinal Carotenoids: Lutein and Zeaxanthin

The xanthophylls lutein and zeaxanthin are the yellow pigments of the carotenoid group of natural photosynthetic pigments. They are the major diet-based pigments concentrated in the human retinal epithelium and absorb blue spectrum ultraviolet light, which is associated with photochemical damage and reactive oxygen species generation. Therefore, they have the capacity to reduce the potency of nascent free radicals and protect the photoreceptor cell layer.5

Richter et al in the Veterans Lutein Antioxidant Supplementation Trial (LAST), a double-blind, prospective, placebo-controlled trial, found that after 1 year of daily lutein supplementation (10 mg) plus a mixture of antioxidant vitamins and minerals, ocular pigment density increased and visual acuity improved in comparison to the placebo-treated group of male veterans with dry macular degeneration.6

A case-control study of more than 2,500 patients from the Age-Related Eye Diseases Study (AREDS) found that participants with the highest dietary intake of lutein/zeaxanthin statistically were less likely to have advanced AMD or large or extensive intermediate drusen than those participants with the lowest intake.7

In the multicenter Eye Disease Case Control Study, Seddon et al found, after controlling for hypertension, smoking, age, geographic area, sex, and hypertension, that consumption of vegetables high in carotenoids, especially lutein and zeaxanthin, was associated significantly with a reduced risk for AMD (P = 0.001). Intake of specific carotenoid-rich food items, such as spinach and collard greens, significantly lowered risk for AMD (P < 0.001).8

Cho et al, in a prospective observational study of more than 70,000 women from the Nurses' Health Study and more than 40,000 men from the Health Professionals Follow-Up study (≥ age 50) found that intake of three or more daily servings of fruit was inversely related to the development of exudative (advanced) AMD compared to persons who consumed 1.5 or fewer daily servings (P < 0.004).9

Zinc

Zinc is an essential micronutrient for human metabolism that serves as a cofactor in many enzymatic reactions. It has antioxidant properties and may protect against macular degeneration resulting from oxidative stress.10

AREDS included a randomized clinical trial of more than 3,600 nutritionally replete adults 55-80 years of age with AMD. Those study patients with intermediate or advanced AMD in the zinc arm or the zinc plus antioxidants (vitamins C, E, and beta-carotene) arm showed a 27% reduction in visual deterioration compared with the placebo group (P = 0.008).11

Marine Omega-3-Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids

Omega-3 fatty acids are essential fatty acids (i.e., humans cannot synthesize these essential components); therefore, they must be included in the diet. Docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) and eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) are LCο3PUFAs obtained from marine dietary sources such as tuna, sardines, salmon, and trout.12

DHA is the most abundant long-chain polysaturated fatty acid in the retina and constitutes the major structural lipid in retinal outer segment membranes. During the normal visual cycle, the outer photoreceptor cells of the retina are constantly shed.13 Given that these marine omega-3 fatty acids often form a minor part of an individual's diet, constituting ≤ 0.1%-0.2% of energy intake,14 such a deficiency may initiate AMD.15 Additionally, long-chain omega-3 fatty acids may protect against oxidative and inflammatory retinal damage, which are key pathologic processes in AMD.16

EPA depresses VEGF-specific receptor activation and expression in the photoreceptor cells. VEGF plays an important role in the promotion of choroidal neovascularization as well as leukocyte and macrophage chemotaxis seen in exudative macular degeneration.17

A meta-analysis by Chong et al, consisting of epidemiological and case control studies, suggests that consumption of fish rich in omega-3 fatty acids twice weekly compared with an intake of less than once per month was associated with a reduced risk of both early and late AMD. The lack of randomized, placebo-controlled intervention trial data, however, precludes the determination of a cause and effect relationship.18

A more recent cross-sectional study by Swenor et al of dietary and ophthalmological data on 2,300 coastal Maryland residents aged 65-84 found that patients with advanced features of AMD (exudative type) were significantly less likely to consume fish/shellfish high in omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids. The small number of patients with exudative AMD and the study design, however, also make it impossible to conclude there are definitive causal associations.19

A large, multicenter Phase III randomized, controlled trial, The Age-Related Eye Disease Study 2 (AREDS2), currently is ongoing and is designed to evaluate the roles of omega-3 fatty acid (EPA and DHA) and/or carotenoid (lutein and zeaxanthin) supplementation vs. placebo on the development of advanced AMD and to study the effects of elimination of the beta-carotene component and reducing the zinc dosage in the original AREDS formulation on the development and progression of AMD.20

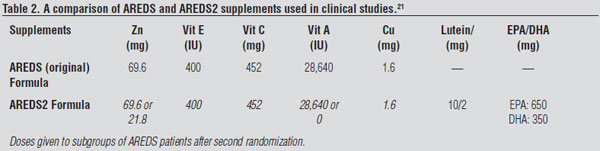

Dosage: AREDS vs. AREDS2 Formulation

The standard of care for patients with AMD is modification of risk factors such as improving blood pressure and lipid levels, and regular consumption, if clinically indicated, of the AREDS formulation of antioxidant vitamins and minerals. Products composed of the original AREDS formulation are Bausch and Lomb's PreserVision AREDS® or ICaps AREDS®.21 Table 2 (see above) lists ingredients for the AREDS and AREDS2 study supplements used for eye health studies sponsored by the National Institutes of Health.

Table 2. A comparison of AREDS and AREDS2 supplement s used in clinical studies.21

s used in clinical studies.21

Since zeaxanthin is a stereoisomer of lutein, they are often found together. A daily supplement of lutein/ zeaxanthin can be added to the standard AREDS formula for patients with AMD. A safe and effective dose of lutein used for protection against AMD progression in studies was 10 mg daily. Lutein- and zeaxanthin-rich foods can be incorporated into the diet (see Table 3, above),22 and these whole foods increase dietary fiber and provide patients with other sources from which to obtain their recommended 5 daily servings of fruit and vegetables. CDC has a helpful website at www.fruitsandveggiesmatter.gov, which includes a calculator and menu planner that encourages patients to eat more fruits and vegetables.

Table 3. Lutein/zeaxantin content of foods.22

Diet alone, however, cannot provide the same levels of the vitamins and minerals present in the AREDS formulation. Multivitamin supplements do not contain the same high levels of vitamins and minerals present in the AREDS formula but they do contain important vitamins not included in the AREDS formula. At the present time in the AREDS2 trial, study enrollees who wish to take an additional multivitamin supplement in addition to their study drug have been advised to take Centrum® Silver.20

Adverse Events

Current smokers or former smokers who have quit within the past year and have or are at risk for AMD should not take the AREDS formulation with beta-carotene due to the increased risk of lung cancer and mortality.23

Since the zinc in the AREDS formulation is above the tolerable upper intake level of 40 mg generally considered safe in adults, copper has been added to offset the negative effect of this zinc dosage on copper absorption. Prolonged ingestion of amounts greater than the tolerable upper intake level can suppress immunity, decrease high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels and cause hypochromic, microcytic anemia. Other adverse effects of excess zinc ingestion include metallic taste, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal cramping.24 Patients in the zinc arm of AREDS experienced increased hospitalizations for genitourinary complications (urinary tract infections and nephrolithiasis) vs. the non-zinc arms of the study (P = 0.003).25 Therefore, a dose reduction may be beneficial and AREDS2 will be using a lower dose of zinc.

In the United States, Bausch and Lomb voluntarily recalled one specific product, the PreserVision® Eye Vitamin AREDS 2 formula with omega-3 soft gels, due to swallowing difficulties with choking sensations reported in persons older than 70 years of age.26

Conclusion

AMD has multiple causative components including genetic susceptibility, aging, and environmental factors such as exposure to ultraviolet light. Lifestyle interventions that optimize blood pressure and serum lipids may improve ocular as well as overall health. There is evidence that both dietary and pharmacologic lutein and zeaxanthin supplementation decrease the likelihood of AMD progression. Further evidence will be needed from the AREDS2 trial to determine the optimal daily dosage of zinc and whether daily long-chain omega-3 fatty acid intake through diet or supplementation also will prevent or delay progression of AMD.

Recommendations

Patients who are diagnosed with or have risk factors for AMD should receive assistance with smoking cessation as well as optimization of blood pressure and lipid profiles as clinically indicated. An increased intake of dietary carotenoids, particularly foods high in the retinal xanthophylls, lutein, and zeaxanthin (see Table 3) may be an additional way for patients to attain their five daily servings of vegetables and fruit as well as mitigate their risk for AMD. Although consideration also could be given to taking an AREDS supplement, they should not be prescribed for smokers and patients with a history of nephrolithiasis. Results from the AREDS2 trial due in 2012 should elucidate whether marine long-chain omega-3 fatty acids supplementation will be beneficial for the secondary prevention of AMD.

References

1. Eye Diseases Prevalence Research Group. Prevalence of age-related macular degeneration in the United States. Arch Ophthalmol 2004;122:564-572.

2. Boulton M, Dayhaw-Barker P. The role of the retinal pigment epithelium: Topographical variation and ageing changes. Eye 2001;15(part 3):384-389.

3. Klein R, et al. The prevalence of age-related macular degeneration and associated risk factors. Arch Ophth 2010;128:750-758.

4. Smith TC. Age Related macular degeneration. New developments in treatment. Australian Family Physician 2007;35:359-361.

5. Bone RA, et al. Preliminary identification of the human macular pigment. Vision Res 1985;25:1531-1535.

6. Richter S, et al. Double-masked, placebo-controlled, randomized trial of lutein and antioxidant supplementation in the intervention of atrophic age-related macular degeneration: The Veterans LAST study (Lutein Antioxidant Supplementation Trial). Optometry 2004;75: 216-230.

7. Age Related Eye Disease Study Research Group. The relationship of dietary carotenoid and vitamin A, E, and C intake with age-related macular degeneration in a case-control study. AREDS Report NO. 22. Arch Ophthalmol 2007;125:1225-1232.

8. Seddon JM, et al. Dietary carotenoids, vitamins A, C, and E and advanced age-related macular degeneration. Eye Disease Case-Control Study Group. JAMA 1994;272:1413-1420.

9. Cho E, et al. Prospective study of intake of fruits, vegetables, vitamins, and carotenoids and risk of age-related maculopathy. Arch Ophthalmol 2004;122:883-892.

10. Grahn BH, et al. Zinc and the eye. J Am Coll Nutr 2001;20(2 suppl):106-118.

11. Age-Related Eye Disease Study Research Group. A randomized, placebo-controlled, clinical trial of high-dose supplementation with vitamins C and E, beta carotene, and zinc for age-related macular degeneration and vision loss: AREDS report no. 8. Arch Ophthalmol 2001;119:1417-1436.

12. Chong EW, et al. Facts on fats. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol 2006;34:464-471.

13. Neuringer M, et al. The essentiality of n-3 fatty acids for brain development and function of the retina and brain. Ann Rev Nutr 1988;8:517-541.

14. Gebauer S, et al. Dietary n-6:n-3 fatty acid ratio and health. In: Akoh CC, Lai O-M, eds. Healthful Lipids. Urbana, IL: AOCS Press: 2005:221-248

15. Bazan NG. The metabolism of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids in the eye: The possible role of docosahexaenoic acid and docosanoids in retinal physiology and ocular pathology. Prog Clin Biol Res 1989;312:95-112.

16. Donoso LA, et al. The role of inflammation in the pathogenesis of age-related macular degeneration. Surv Ophthalmol 2006;51:137-152.

17. Farrara N, Davis-Smith T. The biology of vascular endothelial growth factor. Endocr Rev 1997;18:4-25.

18. Chong EWT, et al. Dietary omega-3 fatty acid and fish intake in the primary prevention of age-related macular degeneration. Arch Ophthalmol 2008;126:826-833.

19. Swenor BK, et al. The impact of fish and shellfish consumption on age-related macular degereration. Ophthalmology 2010; article in press.

20. Age-Related Eye Disease Study 2 Protocol. Available at: https://web.emmes.com/study/areds2/resources/areds2_protocol.pdf. Accessed July 30, 2010.

21. ConsumerLab.com Product Review: Eye Health Supplements. Available at: www.consumerlab.com/reviews/Lutein_Zeaxanthin_Astaxanthin_Supplements_Review/lutein/#comparison. Accessed July 16, 2010.

22. USDA-NCC. Carotenoid Database for U.S. Foods-1998. Available at: www.nal.usda.gov/fnic/foodcomp/Data/car98/car_tble.pdf. Accessed July 29, 2010.

23. The effect of vitamin E and beta carotene on the incidence of lung cancer and other cancers in male smokers. The Alpha-Tocopherol, Beta Carotene Cancer Prevention Study Group. N Engl J Med 1994;330:1029-1035.

24. Saper RB, Rash R. Zinc: An essential micronutrient. Am Fam Physician 2010;2009;79:768-777.

25. Johnson AR, et al. High dose zinc increases hospital admissions due to genitourinary complications. J Urol 2007;177:639-643.

26. Voluntary Recall of PreserVision® Eye Vitamins 2 Formula in the United States. Available at: www.fda.gov/Safety/Recalls/ucm220353.htm. Accessed Aug. 20, 2010.

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is the leading cause of blindness in adults in the United States and western Europe. Approximately 26% of adults older than 65 have some form of AMD.Subscribe Now for Access

You have reached your article limit for the month. We hope you found our articles both enjoyable and insightful. For information on new subscriptions, product trials, alternative billing arrangements or group and site discounts please call 800-688-2421. We look forward to having you as a long-term member of the Relias Media community.