Throat Infections Part I: Low-Acuity Disease Entities

July 1, 2021

AUTHOR

Daniel Migliaccio, MD, Clinical Assistant Professor, Ultrasound Fellowship Director, Department of Emergency Medicine, Universityof North Carolina, Chapel Hill

PEER REVIEWER

Catherine Marco, MD, Wright State University, Dayton, OH

Executive Summary

- The most common presentation of oropharyngeal candidiasis involves the formation of a pseudomembrane characterized by white plaques on an erythematous base. The exudate resembles cottage cheese in appearance, and the pseudomembrane can be easily scraped off.

- Behçet’s syndrome is an inflammatory disorder with multisystem involvement, including the vascular system, gastrointestinal system, and neurological system. It may present with recurrent oral and genital ulcerations.

- Herpetic lesions will begin as vesicular as opposed to aphthous lesions, which begin with a small macule. Additionally, herpes labialis typically affects the hard palate and/or vermilion border, as opposed to aphthous ulcerations, which affect the buccal or lingual mucosa.

- Patients with parotitis typically will present with rather rapid onset of parotid gland swelling and tenderness in that area. Upon examination, a patient will have a significant amount of swelling and edema over the parotid gland, and purulence may be expressed from Stensen’s duct. A patient may have an associated fever and trismus secondary to masseter muscle spasm. The prodrome of myalgias, headache, and fatigue can be seen with mumps.

- Viral pharyngitis is the most common etiology of sore throat among pediatric patients. Viral infections can lead to the inflammation of the pharynx and/or tonsils. There are multiple possible viruses that can cause viral pharyngitis. Patients typically will present with sore throat, fever, and odynophagia. Some of the most common viruses implicated in viral pharyngitis include rhinovirus, adenovirus, coxsackie A virus, Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), and influenza. Respiratory viruses, such as rhinovirus and adenovirus, along with enteroviruses frequently are more encountered etiologies of viral pharyngitis in infants and younger children.

- Coxsackie A virus can cause herpangina or hand, foot, and mouth disease. Both are common in infants and young children. The most common etiology is coxsackievirus A 16, which is a member of the Enterovirus genus. Complications of coxsackie A virus include myocarditis, and it is one of the most common etiologies of viral myocarditis in the United States.

- The clinical syndrome of EBV involves a prodrome of systemic symptoms of fever, malaise, fatigue, and headache prior to the sore throat or pharyngitis development. Patients may have an associated exudate as well as posterior cervical chain lymphadenopathy. Less commonly, palatal petechiae and diffuse maculopapular rashes may be encountered. It is important to consider HIV in adolescents with risk factors presenting with this constellation of symptoms, since these symptoms may be seen in acute HIV infection as well.

- Splenomegaly also is encountered frequently with infectious mononucleosus and is seen in up to half of patients who develop infectious mononucleosis. It is important to examine the spleen and potentially obtain an ultrasound to determine the extent of the splenomegaly. Splenic rupture can be associated with infectious mononucleosis and can even occur without trauma. Is important to counsel patients to avoid physical contact, specifically contact sports, for at least three weeks following the diagnosis of infectious mononucleosis, and they should be evaluated by their primary care physician prior to returning to sports.

- Group A beta-hemolytic Streptococcus pharyngitis presents with an abrupt onset of sore throat with associated systemic symptoms, such as headache, malaise, and decreased oral intake secondary to odynophagia. Patients may present with edematous tonsils, tonsillar exudate, and tender anterior cervical chain lymphadenopathy.

Introduction

Pediatric patients with sore throat are a common presentation in the emergency department. Presentation may vary from low-acuity, self-limited viral pharyngitis to infections leading to sepsis or airway compromise. Emergency medicine providers must be able to differentiate among vast differential diagnoses when evaluating pediatric patients with sore throat. It is important that emergency providers maintain a systematic approach in the evaluation of these patients to ensure that a potentially life-threatening condition is not missed.

This article will review common pediatric pathologies that present with sore throat, as well as the diagnostic and management strategies for the emergency provider. Part 1 of this article will cover low-acuity disease entities, whereas part 2 will describe more virulent etiologies of sore throat.

Epidemiology

Sore throat is a frequently encountered chief complaint in the emergency department. Each year, they are more than 2 million emergency department visits and more than 7 million outpatient pediatric visits for sore throat.1 Approximately 20% of pediatric emergency department visits for sore throat are secondary to bacterial pharyngitis caused by group A beta-hemolytic Streptococcus (GABHS), also known as “strep throat.”2 The peak incidence of GAHBS pharyngitis is in children ages 5 to 15 years.3

Additionally, it is estimated that $200-$500 million is spent annually on the evaluation of pediatric pharyngitis.4 Multiple guidelines, such as the Infectious Diseases Society of America, American Heart Association, and the American Academy of Pediatrics, have generated criteria to facilitate and attempt to streamline clinical care for providers in the assessment of sore throat regarding testing and treatment strategies for patients with sore throat and, potentially, GABHS.5

However, inappropriate antibiotic prescribing for patients presenting with sore throat still continues well into the current COVID-19 pandemic. Unnecessary antibiotic use leads to increased healthcare costs, the potential for antibiotic resistance, and the potential for patient side effects/allergic reactions. It is important for emergency providers to learn appropriate prescribing behavior in an effort to limit these complications.

The presentation and management of various diagnoses that may present with sore throat will be discussed under the specific disease entity section. It is crucial that emergency physicians be attuned to potential clues for severe etiologies of sore throat and complicated cases of pharyngitis to avoid missed diagnoses and potential risk for increased morbidity and mortality.

History and Exam

Thorough history taking may help facilitate a diagnosis in patients presenting with sore throat. Certain key features are important to note. Shortness of breath, stridor, and/or increased work of breathing can indicate a potential obstructive process, such as epiglottitis, deep-seated neck space abscess, and possible concomitant pneumonia, such as with COVID-19. Fever is a common presentation with infectious etiologies of sore throat and may help exclude the diagnosis of allergies. It also is important to note any systemic symptoms, such as fatigue, since it may help facilitate a diagnosis of infectious mononucleosis.

The onset of symptoms also is important to note. A subacute presentation typically can be seen in viral and/or bacterial pharyngitis. However, an abrupt presentation can be concerning for acute epiglottitis. Similarly, vaccination status is important to note, since unimmunized children are at increased risk from diphtheria and Haemophilus influenzae (epiglottitis).

Other historical considerations include concomitant medical comorbidities, such as immunocompromising conditions such as a history of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Important social considerations include the presence of sick contacts, since pharyngitis typically is seen in clusters of family members. Similarly, it is important to note patient’s sexual history, including specifically asking a patient about receptive oral intercourse, since gonococcal pharyngitis can present as a mimic to strep throat.

Physical examination includes a thorough evaluation of patient vital signs, noting any significant tachypnea, fever, and the presence or absence of hypoxia. Immediately afterward, or even concomitantly, an assessment of the airway is crucial. The presence of stridor suggests upper airway compromise and warrants emergent evaluation and expedited workup and management. The provider should obtain a general sense or evaluation of the patient’s appearance, such as being toxic (or in acute distress) vs. uncomfortable (but in no acute distress).

However, it is important to note that pediatric patients may be rather well-appearing later into the course of the various diseases presented in this review. The patient's appearance can assist emergency practitioners in deciding the rapidity of management that is required and appropriate disposition. Pediatric patients with stridor, toxic appearance, or in tripod positioning can be concerning for epiglottitis and/or deep-seated neck space infection. These patients require immediate evaluation and expedited management/disposition, preferably in a controlled environment, such as in an operating room, with definitive management, evaluation, and, most importantly, airway protection.

An initially nontoxic-appearing child then should have a thorough evaluation of the oropharynx performed at the bedside. The presence of trismus typically indicates inflammation of the masseter muscle and is associated with more severe oropharyngeal infections. For example, trismus is seen commonly in patients with peritonsillar abscesses.

The presence of tonsillar exudate and/or edema is important to note. Exudate may be seen in bacterial and/or viral pharyngitis, as well as with candidal pharyngitis. It is important to note the quality, quantity, color, and consistency of the exudate, since different disease entities can be associated with particular exudate characteristics. The presence of vesicles may suggest a diagnosis of a viral pharyngitis from coxsackievirus and/or herpetic stomatitis as the cause of a patient’s symptoms.

Tonsillar symmetry should be noted, since tonsillar enlargement, along with potential uvular deviation, can be indicative of peritonsillar cellulitis and abscess. Concomitant evaluation of the lymph nodes can demonstrate associated tender lymphadenopathy, which can be seen in some of the etiologies of sore throat, such as GABHS and diphtheria. Oropharyngeal edema, strawberry tongue, and cracked lips, along with fever, can be indicative of a diagnosis of Kawasaki disease. It is also important to evaluate the tympanic membranes, since ear pain can occur secondary to referred pain from nonoropharyngeal etiologies of sore throat, such as sinusitis, dental infections, and/or allergies.

Besides a thorough evaluation of the patient’s head and neck, it is important for the provider to assess the patient systemically, including an evaluation of the skin. Examples of skin findings include a diffuse erythematous rash, which can be seen in scarlet fever; a maculopapular rash on the palms and soles, which can be seen in coxsackie infections, such as hand, foot, and mouth disease; and a gun metal rash, can be seen in patients with disseminated gonorrhea. Most often, the history and physical exam are all a provider needs to facilitate the diagnosis. Specific diagnostic tests are discussed within each disease pathology presented later.

Disease Entities

Oral Candidiasis

Background. Oral candidiasis is common among infants and immunocompromised patients and presents with white plaques on an erythematous base. Typically, there is alteration of normal oropharyngeal flora that leads to an overgrowth of a fungus that can cause oral pharyngeal candidiasis, also known as thrush. This is very common in young infants, but it also can be seen in older children who have been treated recently with antibiotics, are on inhaled glucocorticoids for asthma, and/or have a concomitant immunocompromised state, such as acquired immunodeficiency syndrome.6,7

While there is a variety of Candida species that can lead to thrush, the most common is Candida albicans.8

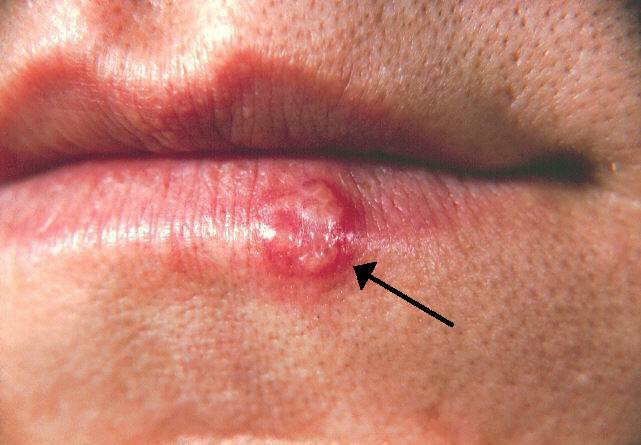

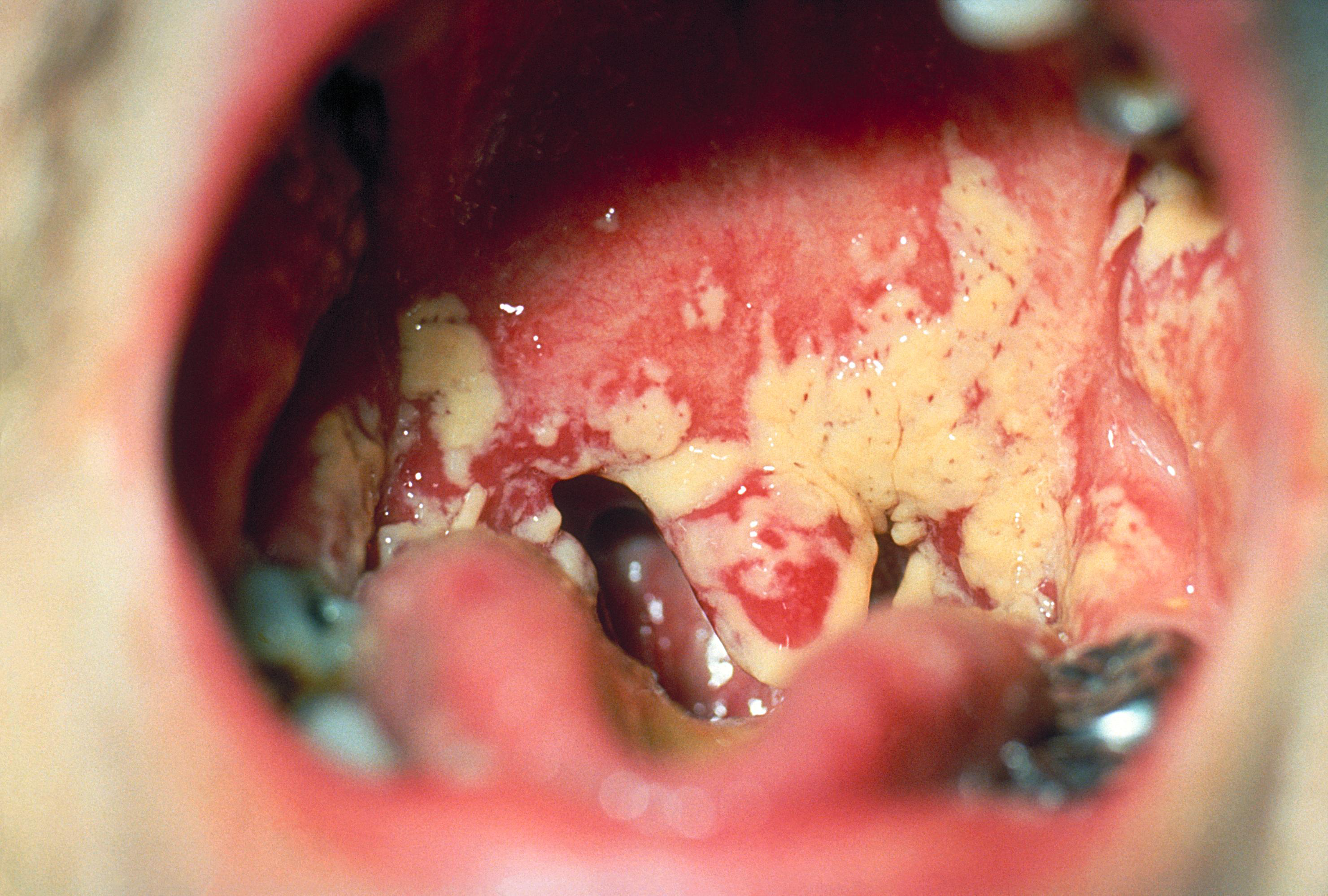

Presentation. The most common presentation of oropharyngeal candidiasis involves the formation of a pseudomembrane characterized by white plaques on an erythematous base. The exudate resembles cottage cheese in appearance, and the pseudomembrane can be easily scraped off. (See Figure 1.) Removing the white plaques can lead to a small amount of underlying bleeding. Children typically will present with odynophagia, while older children may present with ageusia.

Figure 1. Oral Candidiasis |

|

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. |

Diagnosis. As mentioned, the diagnosis of oral pharyngeal candidiasis is clinical and based on classic findings of a white plaque on an erythematous base that is easily scraped off. If there is a diagnostic concern, a Gram stain, fungal culture, or potassium hydroxide preparation demonstrating budding yeasts with or without hyphae can be performed, which clinches the diagnosis. The clinician must consider the diagnosis of HIV for children with recurrent oropharyngeal candidiasis or older children who develop candidiasis without predisposing factors, such as inhaled glucocorticoids, concomitant chemotherapy, and/or recent antibiotic usage.9

Management. The mainstay of treatment for oral candidiasis involves antifungal therapy. For immunocompetent infants between 1 month and 1 year of age, the first-line treatment is oral nystatin suspension (swish and swallow) of 200,000 units, four times a day for seven to 14 days. For immunocompetent children with mild infection who are older than 1 year of age, the treatment is nystatin suspension 400,000 to 600,000 units four times per day for seven to 14 days.

In patients who are immunocompromised and/or who have severe infection, oral fluconazole is recommended. The recommended dose in these patients is 6 mg/kg orally once on the first day, followed by 3 mg/kg once per day for seven to 14 days. Patients with severe thrush and odynophagia who are unable to tolerate fluids and/or oral medications may need to be hospitalized for intravenous (IV) fluconazole.9

Aphthous Stomatitis (Canker Sore)

Background. Aphthous stomatitis, also known as a canker sore, is the most common type of recurrent noncontagious oral ulcer. Risk factors for the recurrence of aphthous ulcers include local trauma, such as biting one’s lip, and genetics.10 Stress and anxiety also can provoke lesions to recur. \

Aphthous ulcers can develop in the absence of underlying conditions. They also can be seen in the setting of methotrexate use or with underlying diseases, such as systemic lupus erythematosus, neutropenia, inflammatory bowel disease, and/or celiac disease.

Furthermore, they also can be seen in patients with Behçet’s syndrome. Behçet’s syndrome is an inflammatory disorder with multisystem involvement, including the vascular system, gastrointestinal system, and neurological system. It can present with oral and genital ulcerations. Recurrent oral ulcerations should make emergency providers consider this diagnosis.

Presentation. Aphthous stomatitis presents with painful oral lesions that typically are comprised of localized ulceration. Usually, patients will have prodromal sensations, including burning, itching, or stinging. The ulcerations begin with small erythematous macules that ultimately develop into a shallow ulcer on the oral mucosa, most commonly on the buccal and lingual mucosa. (See Figure 2.) The ulcerations have a punched-out appearance, typically in a circular pattern with an erythematous halo.

Figure 2. Shallow Ulcer on the Lower Lip Consistent with Aphthous Ulcer

Courtesy of Genppy. Aphthous ulcer. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Aphthous_ulcer.jpg

Diagnosis. The diagnosis of aphthous stomatitis is through clinical examination. Differential diagnosis includes herpes labialis.11 While it is sometimes difficult to differentiate the two disease entities, there are some important diagnostic findings that can help providers. Herpetic lesions will begin as vesicular as opposed to aphthous lesions, which begin with a small macule.

Additionally, herpes labialis typically affects the hard palate and/or vermilion border, as opposed to aphthous ulcerations, which affect the buccal or lingual mucosa. (See Figure 3.). If there is a diagnostic dilemma, a sample of the lesion may be sent for viral culture. A Tzanck smear of the lesion with a Giemsa stain under the microscope to determine the presence of multinucleated giant cells seen in herpes virus infections is no longer routinely performed, since the procedure lacks sensitivity compared to viral culture and/or polymerase chain reaction.12

Figure 3. Herpes Labialis |

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. |

Management. The management of aphthous ulcerations is mainly related to analgesia. There typically is spontaneous resolution of the ulcerations within seven to 10 days. Topical anesthetics, such as mucosal lidocaine, may alleviate some of the patient’s pain. Antimicrobial mouthwashes also may be provided, mostly for comfort or if there is a concern for a superimposed bacterial infection, although that is rare.13

Sialolithiasis

Background. Sialolithiasis occurs when calcium deposits form a stone in a salivary duct, ultimately leading to obstruction in the flow of saliva. Concomitant sialoadenitis, or inflammation of the salivary gland, can occur. The most common locations for sialolithiasis involve the submandibular gland and Wharton’s duct, as well as the parotid gland and Stensen’s duct. It also can involve the sublingual gland. Salivary stones infrequently are seen in children, but they are more common in male smokers between the ages of 30 and 60 years.14

Presentation. Most salivary stones occur in the submandibular glands, and obstruction of salivary flow typically will lead to swelling there that often is painful or sialadenitis. Patients will present with unilateral facial, neck, and/or mouth pain, which is exacerbated with eating.

Diagnosis. Diagnosis of sialolithiasis and sialadenitis can be achieved via clinical examination. Palpating the floor of the patient's mouth, palpating along Wharton's duct, and inspecting the orifice Wharton’s duct, and inspecting the orifice located near the frenulum of the tongue may demonstrate a stone, hardening, and/or potentially purulent exudate.15 Frank purulence is concerning for bacterial sialadenitis, which indicates the need for more advanced imaging, such as computed tomography (CT) scanning to determine whether there is an associated abscess that would need operative drainage by an oral maxillofacial surgeon or otolaryngologist.

Similarly, the provider can palpate the buccal mucosa and Stensen’s duct, which is typically near the second upper molar on the buccal mucosa. Tenderness to palpation of the area and/or palpation of a small, hard, mobile stone may confirm the diagnosis.

Imaging may be required if the diagnosis is unclear, if there is concern for suppurative sialoadenitis, if the patient is toxic-appearing, and/or if the patient has a concomitant immunocompromised state. The imaging study of choice typically is CT with IV contrast for delineating potential abscesses.16 Ultrasound may also be useful but is less sensitive in evaluating for abscesses.

Management. Sialolithiasis without evidence of sialadenitis and/or acute infection should be managed with adequate pain control, including anti-inflammatories, and sialagogues, such as lemon drops, to stimulate salivation and promote the passage of the stone. Having the patient massage the affected gland also can provide significant relief. If there is concomitant infection, the patient may require antibiotics. The most common etiology of bacterial sialadenitis is Staphylococcus aureus, but ill-appearing patients should be started on broad-spectrum antibiotics. Abscesses associated with sialadenitis need to be drained by an oral surgeon for source control of the infection.17 Sialadenitis caused by a systemic syndrome, such as Sjögren’s syndrome or sarcoidosis, should be treated supportively.

Parotitis

Background. Parotitis involves the inflammation of the parotid gland, and there are multiple etiologies or potential causes. Mumps is a highly infectious and contagious viral etiology of parotitis in children.18 Vaccination efforts have curtailed the prevalence of mumps, but there are occasional outbreaks in areas of patients residing in close quarters. Bacterial parotitis can be seen secondary to staphylococcal and/or anaerobic organism infections. Additionally, there are multiple noninfectious etiologies of parotitis, including systemic disorders, such as sarcoidosis or collagen vascular disorders. Other risk factors for parotitis include sialolithiasis, dehydration, and concomitant oral neoplasm.19

Presentation. Patients with parotitis typically will present with rather rapid onset of parotid gland swelling and tenderness in that area. (See Figure 4.) Upon examination, a patient will have a significant amount of swelling and edema over the parotid gland, and purulence may be expressed from Stensen’s duct. A patient may have an associated fever and trismus secondary to masseter muscle spasm. The prodrome of myalgias, headache, and fatigue can be seen with mumps.20

Figure 4. Parotitis |

Courtesy of Afrodriguezg. Parotiditis. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Parotiditis_(Parotitis;_Mumps).JPG |

Diagnosis. The diagnosis of parotitis is clinical. If there is concern for a bacterial superlative parotitis, imaging such as CT with IV contrast may delineate the presence of an abscess. Similarly, in toxic-appearing children with evidence of sepsis, CT may be useful in evaluating for the spread of the infection to surrounding tissues and/or to delineate any other potential deep neck space infections.

Management. If the etiology of parotitis is viral or noninfectious, treatment involves supportive care, such as hydration and pain control. If there are no contraindications, anti-inflammatory medications, such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), can help alleviate some of the patient’s pain. Sialagogues, along with gentle massage of the affected gland, also may help alleviate some of the discomfort. If the patient has trismus, is unable to tolerate oral fluids, and/or is toxic-appearing with a concern for superimposed bacterial/superlative parotitis, the patient should be admitted for IV antibiotics and IV hydration.21 The antimicrobial selection should include broad-spectrum antibiotics and have adequate coverage against S. aureus as well as anaerobes.

Viral Pharyngitis

Background. Viral pharyngitis is the most common etiology of sore throat among pediatric patients. Viral infections can lead to the inflammation of the pharynx and/or tonsils (also known as tonsillitis). There are multiple possible viruses that can cause viral pharyngitis.22 Patients typically will present with sore throat, fever, and odynophagia. Some of the most common viruses implicated in viral pharyngitis include rhinovirus, adenovirus, coxsackie A virus, Epstein-Barr virus, and influenza. Respiratory viruses, such as rhinovirus and adenovirus, along with enteroviruses (coxsackie A) are frequently more encountered etiologies of viral pharyngitis in infants and younger children. In contrast, teenage patients are more likely to be infected with Epstein-Barr virus, which causes infectious mononucleosis, herpes simplex virus, and, rarely, acute HIV infection.

Another important etiology of sore throat in the current state of the world includes severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). More than half of the children that develop severe acute respiratory syndrome associated with SARS-CoV-2 have concomitant sore throat. Exam typically will demonstrate pharyngeal erythema without exudate. Children with COVID-19 typically will have concomitant respiratory symptoms, such as cough and shortness of breath, along with systemic symptoms of fatigue, fever, and gastrointestinal symptoms of nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea . Children may infrequently become quite ill with COVID-19 and present in a fashion similar to acute respiratory distress syndrome.

Presentation. Adenovirus-associated pharyngitis can present with associated common cold symptoms (coryza), conjunctivitis, fever, and cervical lymphadenitis. A patient can have systemic symptoms, such as associated fever, general malaise, and headache.23 Children can present with exudative pharyngitis with cervical lymphadenopathy similar to infection with group A Streptococcus. Children also can have associated cough and viral pneumonia secondary to adenovirus. This can help differentiate infection with GAHBS, which will be characterized typically by the absence of a cough.24 Outbreaks of adenovirus can be seen in association with close contact, such as schools, or in the summer in swimming pools. The disease is typically self-limited and resolves spontaneously within five to seven days. The diagnosis is clinical, and management is supportive, including analgesics, antipyretics, and hydration (oral is preferred if the patient can tolerate it).

Coxsackie A virus can cause herpangina or hand, foot, and mouth disease. Both are common in infants and young children. The most common etiology is coxsackievirus A 16, which is a member of the Enterovirus genus.25 Coxsackie virus infections also tend to occur in outbreaks, commonly in close quarters, such as daycares, schools, and swimming pools.26 The spread of coxsackievirus occurs via direct contact with open vesicles or bodily fluids such as saliva, and via fecal-oral transmission.27 Patients presenting with herpangina typically will have prodromal fever, fatigue, and anorexia with the development of sore throat. Herpangina leads to painful vesicular lesions that ultimately ulcerate in the posterior oropharynx. (See Figure 5.)

Figure 5. Herpangina |

Courtesy of Klaus D. Peter. Herpangina. https://de.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Datei:Herpangina.jpg |

In contrast, vesicular lesions of hand, foot, and mouth disease typically occur on the anterior portion of the mouth, such as the tongue and lips. Patients with hand, foot, and mouth disease will present with erythematous papules that eventually develop into vesicles and will typically involve the patients’ soles and palms. (See Figure 6.) The disseminated rash typically occurs after the oral lesions appear. Both herpangina and hand, foot, and mouth disease can be quite painful for the patient. Diagnosis is clinical, and management involves supportive care with antipyretics and analgesics. Topical mucosa lidocaine, as well as lozenges, can provide some pain relief. Pedialyte ice pops also can alleviate some of the pain and provide adequate oral hydration.

Figure 6. Rash on Soles of Feet Consistent with Hand, Foot, and Mouth Disease |

Courtesy of Ngufra. Hand, foot, and mouth disease on child feet. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Hand_foot_and_mouth_disease_on_child_feet.jpg |

Rarely, patients who are unable to tolerate oral fluids and who have signs of dehydration may require IV hydration. Complications of coxsackie A virus include myocarditis, and it is one of the most common etiologies of viral myocarditis in the United States.28,29 Symptoms of myocarditis include presentation akin to acute heart failure, with evidence of volume overload, jugular vein distention, hepatomegaly, pulmonary edema, and failure to thrive. Bedside cardiac ultrasound can facilitate diagnosis of myocarditis if a provider is concerned for this diagnosis.

The Epstein-Barr virus is the pathogen that leads to the clinical presentation of infectious mononucleosis. It is a ubiquitous herpes virus that can cause pharyngitis associated with infectious mononucleosis.30 Similar to other herpes viruses, the Epstein-Barr virus enters host cell B and T lymphocytes. Many infections with Epstein-Barr virus are asymptomatic. Adolescents and young adults are more likely to demonstrate symptoms consistent with acute infectious mononucleosis.31 The clinical syndrome involves a prodrome of systemic symptoms of fever, malaise, fatigue, and headache prior to the sore throat or pharyngitis development. Patients may have an associated exudate as well as posterior cervical chain lymphadenopathy.32 Less commonly, palatal petechiae and diffuse maculopapular rashes may be encountered.33,34 It is important to consider HIV in adolescents with risk factors presenting with this constellation of symptoms, since these symptoms may be seen in acute HIV infection as well.35

Patients who have infectious mononucleosis and who receive amoxicillin/ampicillin for presumed strep throat will commonly develop a morbilliform rash. While this can be secondary to an allergic reaction to the penicillin, a systemic rash after the provision of penicillin should indicate to the provider a possibility of infectious mononucleosis as the diagnosis.

Splenomegaly also is encountered frequently and is seen in up to half of patients who develop infectious mononucleosis.36 It is important to examine the spleen and potentially obtain an ultrasound to determine the extent of the splenomegaly. Splenic rupture can be associated with infectious mononucleosis and can even occur without trauma.37 Is important to counsel patients to avoid physical contact, specifically contact sports, for at least three weeks following the diagnosis of infectious mononucleosis, and they should be evaluated by their primary care physician prior to returning to sports. Rarely, Epstein-Barr virus can lead to other numerous complications, including severe prolonged fatigue, meningitis, encephalitis, myocarditis, Guillain-Barré syndrome, hepatitis, hematological disorders, such as aplastic anemia and hemolytic uremic syndrome.

The diagnosis of infectious mononucleosis should be strongly considered in an adolescent presenting with symptoms of pharyngitis, fatigue, and posterior cervical adenopathy with splenomegaly. However, confirmatory testing should be performed. Laboratory testing usually will demonstrate an increased number of lymphocytes in the complete blood count, which usually are atypical in appearance.

However, the confirmatory test involves a heterophile antibody test. Reactive antibodies in patients presenting with these symptoms are diagnostic of an Epstein-Barr virus infection. It is important to make this diagnosis, since it can facilitate discussion about prognosis as well as the risks associated with contact sports. Most patients will have a self-limited illness that will resolve within five to seven days. It is important to encourage oral hydration and analgesics for the sore throat.

Management. The mainstay of management for viral pharyngitis is supportive care, including analgesics with acetaminophen, and NSAIDs, such as ibuprofen. Lozenges also may help in providing some relief from the discomfort associated with pharyngitis. Similarly, salt-water gargles also may alleviate some of the pain.

Using steroids to decrease pain and oropharyngeal edema is controversial. The use of steroids may decrease the length of symptoms, and research has demonstrated this to be approximately 12 hours.38 The provider must weigh the benefits and risks of steroids in each patient. Moreover, in patients with mild symptoms of pharyngitis, avoiding steroids typically is recommended. Patients who are unable to tolerate oral hydration may require IV hydration.

Bacterial/Group A Beta-Hemolytic Streptococcal Pharyngitis

Background. Group A beta-hemolytic Streptococcus (GABHS), also known as Streptococcus pyogenes, is the most common cause of bacterial pharyngitis in children and young adults. GABHS is a gram-positive cocci that grows in chains. It accounts for 20% to 30% of all cases of pharyngitis in pediatric patients 5 to 15 years of age.39 The peak incidence is noted during the winter and early spring. GABHS pharyngitis, or strep throat, is less common among children younger than 3 years of age.4

However, infants exposed to adolescents with strep throat may develop illness and typically will present with nonspecific symptoms, such as fussiness, decreased oral intake, and low-grade fever. Social history taking is important to discuss exposure to potential sick contacts.40

Presentation. GABHS pharyngitis presents with an abrupt onset of sore throat with associated systemic symptoms, such as headache, malaise, and decreased oral intake secondary to odynophagia. Patients may present with edematous tonsils, tonsillar exudate, and tender anterior cervical chain lymphadenopathy.41 (See Figure 7.)

Figure 7. Bilateral Enlarged Tonsils with Exudate |

Courtesy of James Heilman, MD. Pos strep. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Pos_strep.JPG |

Patients presenting with symptoms consistent with streptococcal pharyngitis with a diffuse erythematous rash may have scarlet fever. The rash of scarlet fever has been described as having a sandpaper consistency, sparing the palms and soles. It typically is located initially in the groin and armpits and spreads centripetally toward the trunk and can also present with a strawberry tongue. The rash ultimately desquamates. It may appear as petechial lesions in the antecubital fossa, which are known as Pastia’s lines.

Complications associated with strep throat infection are numerous and relatively infrequent. However, they can lead to significant morbidity and, potentially, mortality. Complications arising from GABHS include deep neck space abscess formation, meningitis, sepsis, bacteremia, and/or delayed complications, such as rheumatic fever, Henoch-Schönlein purpura (immunoglobulin A-mediated vasculitis), and/or glomerulonephritis.42,43

Diagnosis. It is important that emergency providers be able to appropriately diagnose group A streptococcal pharyngitis, since appropriate treatment can decrease the incidence of complications and decrease the rate of disease transmission.2 Additionally, appropriate treatment will reduce the severity and duration of the patient’s symptoms. Since there is no specific clinical presentation that rapidly identifies group A streptococcal pharyngitis, the diagnosis of group A Streptococcus is confirmed with a positive diagnostic test, such as a rapid antigen detection test or throat culture as the gold standard.44 It is no longer recommended to treat patients with suspected group A Streptococcus without a confirmed diagnosis, since that can lead to inappropriate expenses, potential side effects, and antibiotic resistance.45 The decision on screening a patient for strep throat can be facilitated by using the Centor criteria. (See Table 1.) A patient with score of 0 has a 1% to 2.5% likelihood of having strep pharyngitis and may not need testing for GAHBS. Meanwhile, a patient with a score of ≥ 4 has a 51% to 53% likelihood and should be tested. While it is no longer recommended to treat based on clinical criteria, such as Centor, they may help determine which patients should be tested.46,47

Criteria

Table 1. The Modified Centor Criteria | |

Points | |

Age |

|

Exudate on tonsils |

|

Tender anterior cervical lymph nodes |

|

Absence of cough |

|

The Modified Centor Criteria are used to guide workup to estimate the probability that a patient has streptococcal pharyngitis. 1 point = 5% to 10% probability, 2 points = 11% to 17% probability, 3 points = 28% to 35% probability, and 4+ points = 51% to 53% probability. A score of 2+ points indicates a need for evaluation with a rapid strep swab.5 | |

The initial screening test typically is a rapid antigen detection test, given its quick turnaround and immediate results.48 If the initial screening test is negative, the patient will need confirmatory testing with a culture (gold standard).49 Typically, a throat culture’s results will take approximately 24 hours. It is important that appropriate demographic information is available to contact the patient in case of a positive culture result. In patients being evaluated for complications of group A streptococcal pharyngitis, such as acute rheumatic fever and/or poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis, serology testing may be performed, but it is not indicated in the evaluation of acute pharyngitis.

The differential diagnosis for group A streptococcal pharyngitis includes viral pharyngitis, as well as potential other bacterial etiologies, including Neisseria gonorrhoeae.50 N. gonorrhoeae is an infrequent etiology of bacterial pharyngitis that can present in patients who are engaged in receptive oral intercourse. In suspected cases of gonococcal pharyngitis, obtain a nucleic acid amplification test from an oropharyngeal swab or a throat culture, which facilitates diagnosis. Another potential bacterial etiology of pharyngitis is diphtheria, although it is encountered infrequently in developed nations since the implementation of widespread vaccination in the 1930s and 1940s. Diphtheria pharyngitis typically is subacute in onset and presents with a classic gray membrane in the oropharynx. Obtaining the patient’s vaccination history may be crucial in making this diagnosis. Diagnosis is performed via toxin detection and/or throat culture.

Management. As mentioned, treatment of group A Streptococcus pharyngitis with antimicrobial therapy is important in decreasing the duration and severity of a patient’s symptoms and preventing acute and delayed complications resulting from the streptococcal infection. The use of appropriate antibiotics can decrease symptom duration by approximately 24 hours. Without antibiotics, symptoms of streptococcal pharyngitis typically are self-limiting and will resolve on their own within five days.

It has been demonstrated that there is a decreased rate of peritonsillar abscess as well as otitis media development in patients treated with antibiotics for streptococcal pharyngitis.51 Similarly, it is estimated that antibiotic therapy for acute streptococcal pharyngitis will decrease the incidence of acute rheumatic fever by approximately two-thirds.42 The data on the prevention of post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis are less consistent, given the limited number of cases studied. Antibiotic use decreases the number of group A Streptococcus bacteria present in the oropharynx of affected patients by approximately 90% after 24 hours of therapy.52 This is beneficial in decreasing the spread of streptococcal pharyngitis to family members and close contacts.

Guidelines from multiple organizations, including the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Infectious Diseases Society of America, recommend penicillin or amoxicillin as the treatment of choice for group A Streptococcus pharyngitis because of their efficacy, relatively low cost, and availability.5 Amoxicillin is better tasting and typically better tolerated in young children. It can be given once daily at a dose of 50 mg/kg for 10 days or 25 mg/kg twice daily for 10 days. For young adults, penicillin V 500 mg three times daily for 10 days is preferred.

If providers have concerns about patient compliance with oral outpatient medications or if patients have a history of acute rheumatic fever, another treatment option for patients presenting to the emergency department is a single dose of IM benzathine penicillin.53 Alternatives to penicillin include macrolides, clindamycin, or cephalosporin in patients with mild reactions to penicillin (not recommended in patients with prior anaphylaxis to penicillin). Example regimens include cephalexin 500 mg twice daily for 10 days, azithromycin 500 mg orally on day 1 followed by 250 mg on days 2 through 5, or clindamycin 300 mg orally three times daily for 10 days.54 Unfortunately, macrolide resistance is increasing, and local resistance rates are worth noting if data are available.55

Supportive care, including recommendation of salt water gargles, lozenges, and using analgesics (e.g., acetaminophen) or anti-inflammatory medications (NSAIDs), is beneficial for symptom control.56 Adjunctive glucocorticoids also have been used in the symptom control of patients with strep pharyngitis, but they are a controversial option, and robust data currently are lacking. In a meta-analysis, glucocorticoids were shown to decrease symptom duration by 12 hours as compared to standard of care with the above therapy.57 Patients who are toxic-appearing or are unable to tolerate oral fluids may require IV fluids.58

Conclusion

Acute care providers must be able to differentiate among a vast differential diagnoses when evaluating pediatric patients with sore throat. A systematic approach is critical in the evaluation of these patients to ensure that a potentially life-threatening condition is not missed. This article reviewed common pediatric pathologies that present with sore throat, as well as the diagnostic and management strategies for the emergency provider. The next edition will describe more virulent etiologies of sore throat.

References

- Niska R, Bhuiya F, Xu J. National hospital ambulatory medical care survey: 2007 emergency department summary. Natl Health Stat Report 2010;26:1-31.

- Shaikh N, Leonard E, Martin JM. Prevalence of streptococcal pharyngitis and streptococcal carriage in children: A meta-analysis. Pediatrics 2010;126:e557-e564.

- Putto A. Febrile exudative tonsillitis: Viral or streptococcal? Pediatrics 1987;80:6-12.

- Pfoh E, Wessels MR, Goldmann D, Lee GM. Burden and economic cost of group A streptococcal pharyngitis. Pediatrics 2008;121:229-234.

- Shulman ST, Bisno AL, Clegg HW, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis and management of group A streptococcal pharyngitis: 2012 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 2012;55:e86-e102.

- Su CW, Gaskie S, Jamieson B, Triezenberg D. Clinical inquiries. What is the best treatment for oral thrush in healthy infants? J Fam Pract 2008;57:484-485.

- Elden LM, Potsic W. Otolaryngologic emergencies. In: Fleisher GR, Ludwig S, eds. Textbook of Pediatric Emergency Medicine. 6th ed. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins;2010:1545-1550.

- Pappas PG, Kauffman CA, Andes DR, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the management of candidiasis: 2016 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 2016;62:e1-50.

- Fisher BT, Smith PB, Zaoutis TE. Candidiasis. In: Cherry JD, Harrison G, Kaplan SL, et al, eds. Feigin and Cherry’s Textbook of Pediatric Infectious Diseases. 8th ed. Elsevier;2018:2030.

- Lodi G, Varoni E, Robledo-Sierra J, et al. Oral ulcerative lesions. In: Farah C, Balasubramaniam R, McCullough M, eds. Contemporary Oral Medicine. Springer;2017:1-33.

- Habif TP. Warts, herpes simplex, and other viral infections. In: Clinical Dermatology: A Color Guide to Diagnosis and Therapy. 5th ed. Elsevier;2010:454-490.

- Ozcan A, Senol M, Saglam H, et al. Comparison of the Tzanck test and polymerase chain reaction in the diagnosis of cutaneous herpes simplex and varicella zoster virus infections. Int J Dermatol 2007;46:1177-1179.

- Cui RZ, Bruce AJ, Rogers RS 3rd. Recurrent aphthous stomatitis. Clin Dermatol 2016;34:475-481.

- Huoh KC, Eisele DW. Etiologic factors in sialolithiasis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2011;145:935-939.

- Mandel L. Salivary gland disorders. Med Clin North Am 2014;98:1407-1449.

- Thomas WW, Douglas JE, Rassekh CH. Accuracy of ultrasonography and computed tomography in the evaluation of patients undergoing sialendoscopy for sialolithiasis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2017;156:834-839.

- Wallace E, Tauzin M, Hagan J, et al. Management of giant sialoliths: Review of the literature and preliminary experience with interventional sialendoscopy. Laryngoscope 2010;120:1974-1978.

- Dayan GH, Quinlisk MP, Parker AA, et al. Recent resurgence of mumps in the United States. N Engl J Med 2008;358:1580-1589.

- Chen S, Paul BC, Myssiorek D. An algorithm approach to diagnosing bilateral parotid enlargement. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2013;148:732-739.

- Anderson LJ, Seward JF. Mumps epidemiology and immunity: The anatomy of a modern epidemic. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2008;27:S75-S79.

- Chi TH, Yuan CH, Chen HS. Parotid abscess: A retrospective study of 14 cases at a regional hospital in Taiwan. B-ENT 2014;10:315-318.

- Centor RM. Expand the pharyngitis paradigm for adolescents and young adults. Ann Intern Med 2009;151:812-815.

- Dominguez O, Rojo P, de Las Heras S, et al. Clinical presentation and characteristics of pharyngeal adenovirus infections. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2005;24:733-734.

- Edwards KM, Thompson J, Paolini J, Wright PF. Adenovirus infections in young children. Pediatrics 1985;76:420-424.

- Gao L, Zou G, Liao Q, et al. Spectrum of enterovirus serotypes causing uncomplicated hand, foot, and mouth disease and enteroviral diagnostic yield of different clinical samples. Clin Infect Dis 2018;67:1729-1735.

- Richardson M, Elliman D, Maguire H, et al. Evidence base of incubation periods, periods of infectiousness and exclusion policies for the control of communicable diseases in schools and preschools. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2001;20:380-391.

- Yang TO, Arthur Huang K-Y, Chen M-H, et al. Comparison of nonpolio enteroviruses in children with herpangina and hand, foot and mouth disease in Taiwan. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2019;38:887-893.

- Jiang M, Wei D, Ou W-L, et al. Autopsy findings in children with hand, foot, and mouth disease. N Engl J Med 2012;367:91-92.

- Rose NR, Neumann DA, Herskowitz A. Coxsackievirus myocarditis. Adv Intern Med 1992;37:411-429.

- Dunmire SK, Verghese PS, Balfour HH Jr. Primary Epstein-Barr virus infection. J Clin Virol 2018;102:84-92.

- Glomb NWS, Cruz AT. Infectious disease emergencies. In: Shaw KN, Bachur RG, eds. Textbook of Pediatric Emergency Medicine. 7th ed. Wolters Kluwer;2016:838-893.

- Ebell Mh, Call M, Shinholser J, Gardner J. Does this patient have infectious mononucleosis? The rational clinical examination systematic review. JAMA 2016;315:1502-1509.

- Luzuriaga K, Sullivan JL. Infectious mononucleosis. N Engl J Med 2010;362:1993-2000.

- Bonfante G, Dunn A. Rashes in infants and children. In: Tintinalli JE, Stapczynski JS, Ma OJ, eds. Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide. 8th ed. McGraw-Hill;2016:934-953.

- Horwitz CA, Henle W, Henle G, et al. Clinical and laboratory evaluation of infants and children with Epstein-Barr virus-induced infectious mononucleosis: Report of 32 patients (aged 10-48 months). Blood 1981;57:933-938.

- Asgari MM, Begos DG. Spontaneous splenic rupture in infectious mononucleosis: A review. Yale J Biol Med 1997;70:175-182.

- Aldrete JS. Spontaneous rupture of the spleen in patients with infectious mononucleosis. Mayo Clin Proc 1992;67:910-912.

- Tynell E, Aurelius E, Brandell A, et al. Acyclovir and prednisolone treatment of acute infectious mononucleosis: A multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Infect Dis 1996;174:324-331.

- Kronman MP, Zhou C, Mangione-Smith R. Bacterial prevalence and antimicrobial prescribing trends for acute respiratory tract infections. Pediatrics 2014;134:e956-e965.

- Esposito S, Blasi F, Bosis S, et al. Aetiology of acute pharyngitis: The role of atypical bacteria. J Med Microbiol 2004;53:645-651.

- Shaikh N, Swaminathan N, Hooper EG. Accuracy and precision of the signs and symptoms of streptococcal pharyngitis in children: A systematic review. J Pediatr 2012;160:487-493.e3.

- Gerber MA, Baltimore RS, Eaton CB, et al. Prevention of rheumatic fever and diagnosis and treatment of acute streptococcal pharyngitis: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease Committee of the Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, the Interdisciplinary Council on Functional Genomics and Translational Biology, and the Interdisciplinary Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research: Endorsed by the American Academy of Pediatrics. Circulation 2009;119:1541-1551.

- Robertson KA, Volmink JA, Mayosi BM. Antibiotics for the primary prevention of acute rheumatic fever: A meta-analysis. BMC 2005;5:11.

- Pichichero ME. Group A streptococcal tonsillopharyngitis: Cost-effective diagnosis and treatment. Ann Emerg Med 1995;25:390-403.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Group A streptococcal disease: Pharyngitis (strep throat). Updated Nov. 1, 2018. www.cdc.gov/groupastrep/diseases-hcp/strep-throat.html

- McIsaac WJ, Kellner JD, Aufricht P, et al. Empirical validation of guidelines for the management of pharyngitis in children and adults. JAMA 2004;291:1587-1595.

- Fine AM, Nizet V, Mandl KD. Large-scale validation of the Centor and McIsaac scores to predict group A streptococcal pharyngitis. Arch Intern Med 2012;172:847-852.

- Hildreth, AF, Takhar S, Clark MA, Hatten B. Evidence-based evaluation and management of patients with pharyngitis in the emergency department. Emerg Med Pract 2015;17-1-16.

- Miller JM, Binnicker MJ, Campbell S, et al. A guide to utilization of the microbiology laboratory for diagnosis of infectious diseases: 2018 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the American Society for Microbiology. Clin Infect Dis 2018;67:e1-e94.

- Gottlieb M, Long B, Koyfman A. Clinical mimics: An emergency medicine-focused review of streptococcal pharyngitis mimics. J Emerg Med 2018;54:619-629.

- Spinks A, Glasziou PP, Del Mar CB. Antibiotics for sore throat. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;2013:CD000023.

- Schwartz RH, Kim D, Martin M, Pichichero ME. A reappraisal of the minimum duration of antibiotic treatment before approval of return to school for children with streptococcal pharyngitis. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2015;34:1302-1304.

- Cohen JF, Pauchard J-Y, Hjelm N, et al. Efficacy and safety of rapid tests to guide antibiotic prescriptions for sore throat. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2020;6:CD012431.

- ESCMID Sore Throat Guideline Group, Pelucchi C, Grigoryan L, et al. Guideline for the management of acute sore throat. Clin Microbiol Infect 2012;18 (Suppl 1):1-28.

- van Driel ML, De Sutter AI, Habraken H, et al. Different antibiotic treatments for group A streptococcal pharyngitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016:CD004406.

- Group A streptococcal infections. In: Kimberlin DW, Brady MT, Jackson MA, Long SS, eds. Red Book: 2018 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 31st ed. American Academy of Pediatrics;2018:748.

- Sadeghirad B, Siemieniuk RAC, Brignardello-Petersen R, et al. Corticosteroids for treatment of sore throat: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised trials. BMJ 2017;358:j3887.

- Rick A-M, Zaheer HA, Martin JM. Clinical features of group A Streptococcus in children with pharyngitis: Carriers vs. acute infection. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2020;39:483-488.

Subscribe Now for Access

You have reached your article limit for the month. We hope you found our articles both enjoyable and insightful. For information on new subscriptions, product trials, alternative billing arrangements or group and site discounts please call 800-688-2421. We look forward to having you as a long-term member of the Relias Media community.