An Anatomical Review of Trauma to the Mouth and Throat

January 1, 2021

Related Articles

-

Echocardiographic Estimation of Left Atrial Pressure in Atrial Fibrillation Patients

-

Philadelphia Jury Awards $6.8M After Hospital Fails to Find Stomach Perforation

-

Pennsylvania Court Affirms $8 Million Verdict for Failure To Repair Uterine Artery

-

Older Physicians May Need Attention to Ensure Patient Safety

-

Documentation Huddles Improve Quality and Safety

AUTHORS

Creagh Boulger, MD, FACEP, Associate Professor, Department of Emergency Medicine, Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, Columbus

Lauren Moore, MD, Ohio State University, Columbus

Benjamin M. Ostro, MD, Assistant Professor of Emergency Medicine, Ohio State University, Columbus

PEER REVIEWER

Brian L. Springer, MD, FACEP, Associate Professor, Department of Emergency Medicine, Wright State University, Kettering, OH

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

- When repairing a lip laceration, it is crucial to achieve excellent alignment of the vermillion border for optimal cosmetic appearance and healing. This can be done with simple interrupted 5-0 or 6-0 size sutures, regardless of absorbability. They should be removed in five to seven days to reduce the risk of train-track scarring. It is important to approximate deeper structures, including muscular fascia, in a layered approach with absorbable sutures.

- Most tongue lacerations do not require repair and will heal well by secondary intention. Tongue lacerations should be repaired in the following situations: lacerations > 1 cm, leading to an anterior split or “forked” appearance, through and through, large flap, or with active hemorrhage.

- The lower lips, gums, and surrounding skin are innervated by the mental nerve, while the upper lip and overlying skin are innervated by the infraorbital nerves. Mental and infraorbital nerve blocks provide excellent anesthesia to the lower lips and upper lips, respectively, without distorting the anatomy. The tongue is innervated primarily by the lingual nerve and can be anesthetized with an inferior alveolar nerve block.

- Ellis III fractures, crown-root fractures, and complete avulsions are considered true dental emergencies. In the case of an avulsed tooth, if the root of a tooth is exposed, only the crown should be handled. Rinse (but do not scrub) the tooth for no more than 10 seconds with normal saline or tap water, and reimplant it into the socket immediately.

- If there are multiple tooth dislocations in a row, have a high suspicion for alveolar fracture. Facial bone computed tomography (CT) without contrast can detect small fractures in this setting.

- Retropharyngeal trauma may lead to airway compromise and vascular injury and should be evaluated with imaging. A lateral neck X-ray can be obtained in an asymptomatic, oriented patient without signs of airway or vascular compromise on exam. For patients with concerning exam findings, such as muffled voice, limited neck range of motion, intraoral hematomas, active bleeding from the oral cavity, and penetrating wounds to the lateral palate, a CT angiography of the head and neck should be obtained. In such patients, the airway should be secured early and prior to image acquisition.

- Given the high rate of morbidity and mortality associated with delayed or missed diagnosis of blunt neck injuries, it is important to have a high index of suspicion. Signs of severe injury requiring emergent intervention with airway stabilization and surgical exploration include those with tracheal deviation, neck bruising, venous distention, abnormal respiration, hypoxia, and subcutaneous emphysema.

- Blunt extracranial carotid injury (BECCI) also may occur, especially in instances of a hyperextension mechanism. Approximately 40% to 89% of BECCIs are from motor vehicle collisions, 6% to 20% are from assault, and the remainder are from falls or hanging.

Trauma to the mouth and throat is very common. Fortunately, the majority of the injuries are minor, but early and timely recognition of critical, potentially devastating injuries is essential. The authors provide a thorough review highlighting critical injuries and their management.

— Ann M. Dietrich, MD, Editor

Case Example

You are working in a rural emergency department. A 27-year-old intoxicated male presents via emergency medical services (EMS) after he was involved in an assault with a baseball bat. He has no significant medical history and is not on any medications. His vitals are: heart rate 110 beats/min, blood pressure 130/85 mmHg, respiratory rate 20 breaths/min, and temperature of 98.5°F. He is awake, alert, and complaining of a headache and face pain. He has left periorbital swelling, swelling and bruising near the left side angle of the mandible without trismus, mild bleeding from his nares, and his left eye is swollen shut. When you lift his eyelid, his extra-ocular movements are intact, and he has a reactive pupil.

You notice that his voice is mildly muffled, but he is protecting his airway, and EMS states that he has sounded that way the entire 15-minute ride for them. There are no focal neurologic deficits, and cranial nerves are intact. His neck exam reveals a midline trachea, no ecchymoses nor hematomas, and no tenderness to palpation. A computed tomography (CT) scan of his head is without hemorrhage, and the CT of the face is still pending. Twenty minutes later, you get a call that your patient is complaining of having trouble swallowing. What injuries should you consider?

Introduction

Trauma to the head, face, and neck is highly interrelated and can vary from minor cosmetic damage to severe and life-threatening. This article will focus on the pathophysiology, management, and disposition of specific injuries related to the mouth, including lips, dentition, palate, and tongue trauma, as well as to the throat, including the pharynx, larynx, trachea, esophagus, surrounding soft tissues, and vasculature. Given the intertwined nature of this anatomy, rarely is one structure injured without affecting another. Although mouth and throat trauma often coexist with intracranial, spinal, and torso injuries, these areas are beyond the scope of this article.

Mouth Trauma

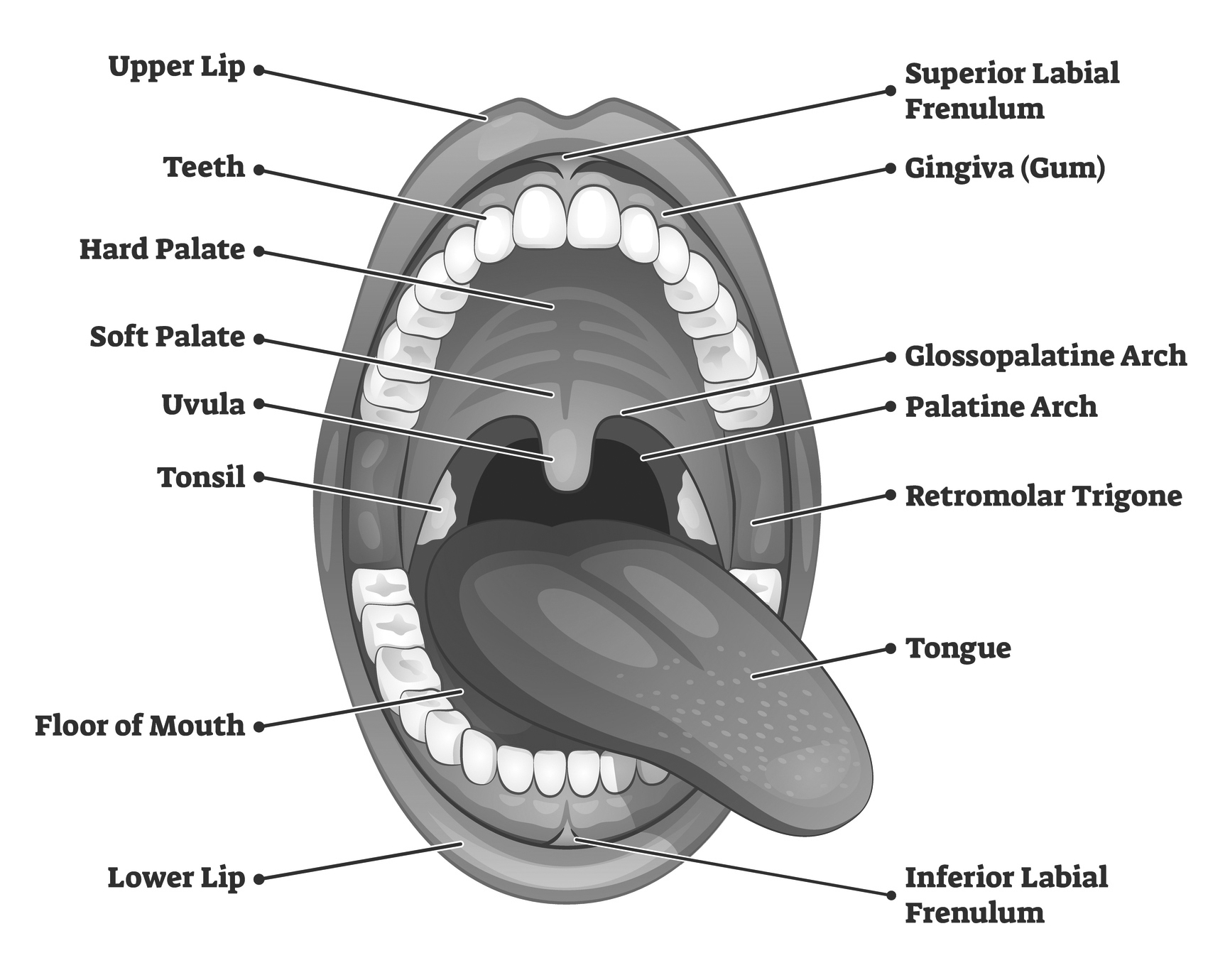

The oral cavity is framed by the lips, cheeks, floor of the mouth, and palate, and it contains structures such as the teeth, tongue, and uvula. Each structure has a particular purpose and, in most cases, can be easily visualized on physical exam. The following sections will explore the anatomy and management of trauma to the tongue, lips, teeth, cheeks, and palate.

Anatomy and Management of Trauma to the Tongue and Lips

The lips are a highly sensitive and vascular structure with great cosmetic importance. The anatomy of the lips is notable for the vermillion border (the demarcation between the lip and surrounding facial skin), the frenulum (the fibrous structure that attaches the inner lip surface to the gums medially), and the commissures (lateral borders of the oral cavity where the lips join). Circumferentially, the orbicularis oris muscles attach to close and protrude the lips.

The tongue is a muscular structure originating at the mandible, temporal bones, and hyoid bone, with a large vascular supply. It is divided medially by a septum that extends its entire length. The tongue is connected to the floor of the mouth by the lingual frenulum. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1. Anatomy of the Oral Cavity |

|

|

Source: Getty Images |

Lacerations are the most common injury to the lip. When repairing a lip laceration, it is crucial to achieve excellent alignment of the vermillion border for optimal cosmetic appearance and healing.1 This can be done with simple interrupted 5-0 or 6-0 size sutures, regardless of absorbability.2 They should be removed in five to seven days to reduce the risk of train-track scarring. It is important to approximate deeper structures, including muscular fascia, in a layered approach with absorbable sutures. Often, this is achieved with a horizontal mattress suture, since simple interrupted sutures may cause undue tension on the deep friable tissue. Closing these deeper structures prior to closure of the epidermis will reduce infection and deformity.2

Laceration repair in the oral mucosa should be completed with absorbable suture, especially if the injury is through and through. Most tongue lacerations do not require repair and will heal well by secondary intention. Tongue lacerations should be repaired in the following situations: lacerations > 1 cm, leading to an anterior split or “forked” appearance, through and through, large flap, or with active hemorrhage. If a small portion of the tongue is bitten off, repair is not required. All lacerations should undergo copious normal saline irrigation and debridement of devitalized tissue. If lacerations are too complex for the provider to comfortably repair, or if there is concern for significant underlying injury, such as an open fracture, subspecialist consultation is recommended.

The lower lips, gums, and surrounding skin are innervated by the mental nerve, while the upper lip and overlying skin are innervated by the infraorbital nerves. Mental and infraorbital nerve blocks provide excellent anesthesia to the lower lips and upper lips, respectively, without distorting the anatomy. The tongue is innervated primarily by the lingual nerve and can be anesthetized with an inferior alveolar nerve block. Blocks are useful adjuncts to oral and parenteral analgesia.3

The oral cavity is rich in bacteria. Despite this, lacerations to the oral mucosa and tongue have a very low incidence of infection, and prophylactic antibiotics are not generally recommended. However, the classic teaching is the prescription of antibiotics for large mucosal wounds > 2 cm and through-and-through wounds.4,5 Emergency providers typically prescribe a five- to seven-day course of antibiotics for animal bites to the lip and face, even though there are few large studies to support this.6 The preferred antibiotic is amoxicillin-clavulanate alone. Doxycycline or a fluoroquinolone with clindamycin can be used if the patient is allergic to penicillin. Longer courses of antibiotics, up to 21 days, are recommended if there is underlying associated bony injury.6 Tetanus should be updated in these scenarios if it has been more than five years since the patient’s previous immunization.

Dental Trauma

Adults have 32 permanent teeth consisting of eight incisors, four cuspids/canines, eight premolars, and 12 molars. The tooth itself is held in the socket (also called the alveolar process) by the periodontal ligament. The root sits in the socket, while the crown projects into the mouth.

The tooth is comprised of four layers: enamel, cementum, dentin, and pulp. The enamel is the durable protective outer covering of the crown of the tooth. The cementum covers the root of the tooth. The dentin lies below the enamel and is comprised of calcified tissue that makes up the bulk of the tooth. The pulp lies below the dentin at the core of the tooth and contains nerves and blood vessels. Teeth are numbered, with numbers 1-16 on the maxilla, with #1 on the patient’s right and #16 on the left. Number 17 then starts on the mandible at the patient’s left, with #32 ending on the right.

Dental trauma is rarely life-threatening, but it does cause significant distress related to pain and cosmesis. The most commonly injured teeth are the incisors, typically related to trauma from falls or assaults.7 Dental injuries are categorized as fractures (Ellis I-III, see Table 1), subluxations (loosening of the tooth in the socket), lunation (loosening and displacement of the tooth), intrusion (tooth driven into the socket), or avulsion (complete removal from the socket).5,8 Further descriptions of the most common types of dental trauma are included in Table 1. In addition to identifying the type of injury, it is also important to note when the injury occurred, the location of missing teeth, and whether the affected tooth is deciduous or permanent.

Table 1. Description and Management of Dental Injuries |

||

|

Dental Injury |

Description |

Management5,8 |

|

Ellis Class I Fracture |

Tooth is fractured at the enamel only |

Conservative; routine dental follow-up |

|

Ellis Class II Fracture |

Tooth fracture includes the enamel and the dentin (dentin is softer and yellowish in color) |

Symptom control since dentin is sensitive to temperature

|

|

Ellis Class III Fracture |

Tooth fracture includes the pulp (and bleeding visible in the fracture indicates pulp involvement) |

Dental EMERGENCY

|

|

Crown-Root Fracture |

Tooth is cracked without avulsed piece — often subclinical, involving element of the crown and or root, sometimes involving pulp and dentin based on extent |

|

|

Subluxation |

Tooth is loose but NOT displaced |

Conservative; soft diet/routine dental follow-up |

|

Luxation |

Tooth is loose AND displaced |

Reposition and splint; urgent dental follow-up |

|

Intrusion |

Tooth is abnormally driven into the socket |

< 3 mm: leave alone, will erupt spontaneously — routine dental follow-up > 3 mm: reposition and stabilize — urgent dental follow-up ** Consider Panorex radiograph for assessment of alveolar bone fracture |

|

Complete Avulsion |

Tooth is completely separated from the socket |

Dental EMERGENCY

|

|

Dental emergencies: follow-up within 24 hours or STAT consult Urgent follow-up: within 48 hours Routine follow-up: > 48 hours |

||

Although they are less common, true dental emergencies require immediate intervention. Ellis III fractures, crown-root fractures, and complete avulsions are considered true dental emergencies.5,8 In the case of an avulsed tooth, if the root of a tooth is exposed, only the crown should be handled. Rinse (but do not scrub) the tooth for no more than 10 seconds with normal saline or tap water, and reimplant it into the socket immediately.5 If unable to do so, store the tooth in Hank’s solution, the patient’s own collected saliva, milk, or saline. If the tooth is allowed to dry completely, it is possible that the periodontal ligament may die and preclude any future attempts at reimplantation. The management of tooth avulsions is time sensitive, and the goal should be reimplantation as soon as possible. The viability of the tooth decreases by 1% for every minute it is out of the mouth. If there is concern for aspiration of an avulsed tooth, obtain a 2-view chest radiograph for further evaluation. Teeth that are subluxed rather than completely avulsed may be managed conservatively with a dental splint and outpatient dentistry followup.

If there are multiple tooth dislocations in a row, have a high suspicion for alveolar fracture. Facial bone CT without contrast can detect small fractures in this setting.5 In the setting of a bleeding socket, inquire about bleeding or coagulation disorders, medications, length of bleeding, and dental manipulations. If direct pressure with gauze does not stop the bleeding, apply a moistened tea bag. The tannic acid in the tea bag has been shown to help stop the bleeding. Other topical hemostatic options include topical tranexamic acid, topical thrombin, or an injection of lidocaine with epinephrine. These patients should be monitored for rebleeding, given the risk of aspiration. Pain can be controlled using a multimodal approach with oral, topical, intramuscular, or intravenous analgesia in addition to dental blocks.9

Trauma to the Buccomandibular Cheek and Palate

The muscles that make up the cheeks include the buccinator, zygomaticus major, and masseter muscles. The buccinator originates at the body of the mandible and inserts at the corner of the mouth to retract and flatten the cheeks. The zygomaticus major and minor facilitate smiling and lateral mouth movement. The masseter, which originates at the zygomatic arch and inserts at the mandible, allows for movement of the jaw. These muscles are innervated primarily by the facial nerve, which has five branches, including the temporal, zygomatic, buccal, mandibular, and cervical branches. The primary blood supply is the maxillary artery, which originates from the external carotid artery.

Much like lip lacerations, small buccal wounds can be left to heal by secondary intent unless they are greater than 1 cm, gaping, or through and through.10 Thorough intraoral exploration should be undertaken. If there is concern for associated parotid duct or gland, pre-auricular, or infraorbital bony injury, a facial CT should be obtained.10 As with all penetrating injuries with a retained foreign body, it is important to leave the penetrating foreign body in place if it is near a large vessel so as not to disrupt the formation of clot or inadvertently cause damage to neurovascular structures. These wounds often require surgical evaluation in the operating room for careful exploration.

The palate, or roof of the mouth, is divided between the anterior, non-mobile, bony hard palate (comprised of the maxilla and palatine bones) and the posterior muscular soft palate. The soft palate is controlled by five separate muscles that are innervated primarily by the vagus nerve for mobility with yawning, breathing, eating, etc. The greater palatine arteries run anteriorly and are the primary blood supply. Fortunately, primary palate trauma is not a common presentation in adults and is usually a concern only when there is penetrating trauma to the oral cavity.11 Penetrating injuries can vary from benign lacerations or contusions to those that cause significant neurovascular compromise. In some instances, intraoral penetrating trauma can injure the carotid artery, leading to intimal tear and formation of thrombus, which may predispose the patient to stroke up to 72 hours after the injury.11,12

Retropharyngeal trauma may lead to airway compromise and vascular injury and should be evaluated with imaging. A lateral neck X-ray can be obtained in an asymptomatic, oriented patient without signs of airway or vascular compromise on exam. For patients with concerning exam findings, such as muffled voice, limited neck range of motion, intraoral hematomas, active bleeding from the oral cavity, and penetrating wounds to the lateral palate, a CT angiography (CTA) of the head and neck should be obtained.11 In such patients, the airway should be secured early and prior to image acquisition.

In stable pregnant patients, consent for CT should be obtained. Imaging of the head and neck provides a negligible risk of radiation exposure to the fetus, whereas the risk of harm to the mother and fetus from a missed or delayed diagnosis is high.13

Throat Trauma

The throat contains multiple vital structures, including the trachea, the esophagus, and the carotid arteries. Not surprisingly, trauma to the throat, especially penetrating trauma, is associated with high mortality.14 These injuries seldom occur in isolation.15 In many of these injuries, the threat of airway compromise requires swift but careful intervention via mechanisms that will be discussed in the next section.

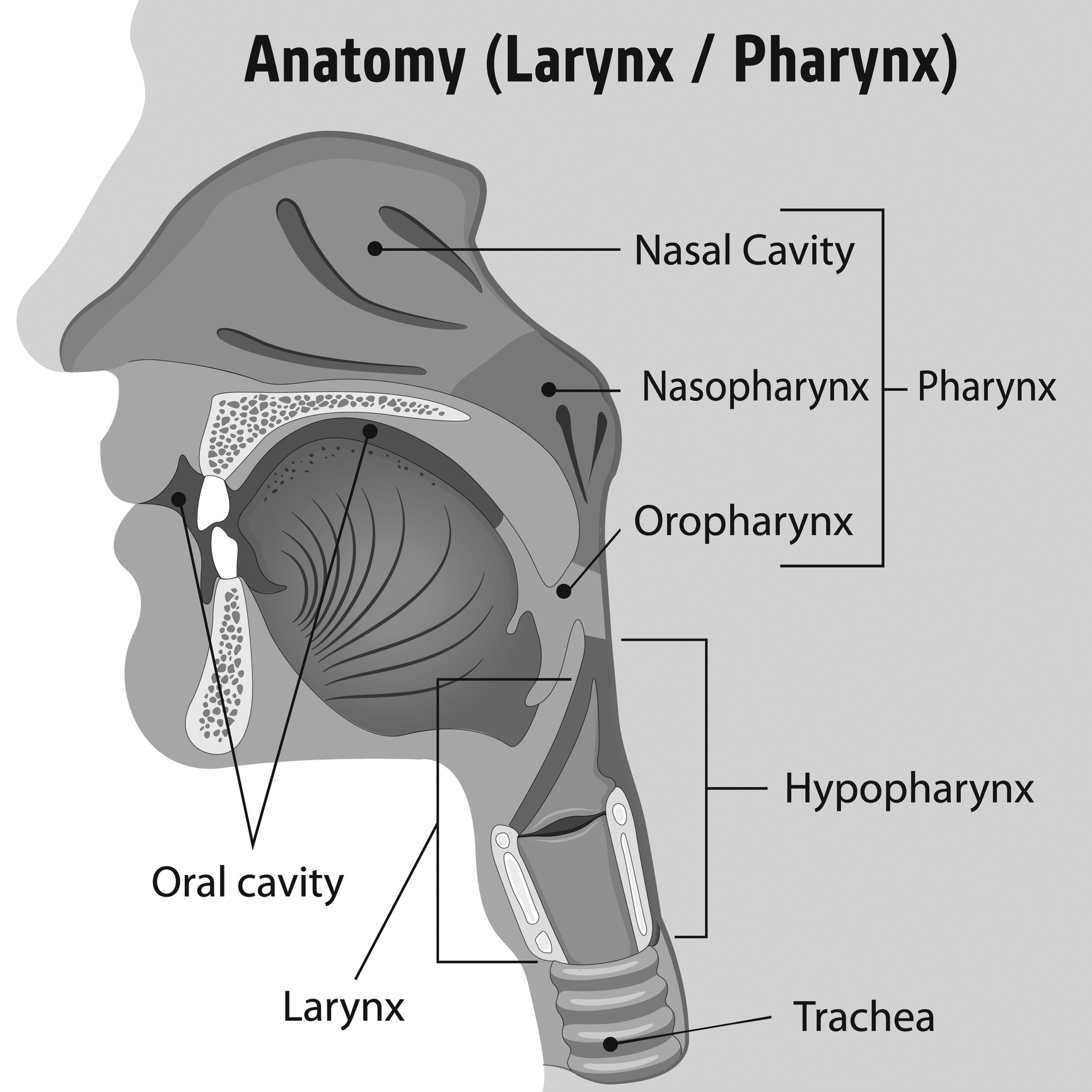

Basic Anatomy Review

Continuing from the mouth anatomy described earlier, the pharynx connects the posterior oral and nasal cavities to both the esophagus (oropharynx) and, more distally, the larynx (laryngopharynx or hypopharynx). The epiglottis protrudes from the base of the tongue and folds over the larynx to prevent aspiration of food and saliva into the lungs during swallowing.16 (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2. Anatomy of the Pharynx |

|

|

Source: Getty Images |

Trauma experts divide the anatomy of the throat into three zones.6 (See Figure 3.) Zone I extends from the clavicles to the inferior aspect of the cricoid cartilage and contains the thoracic outlet, the thoracic duct, and the thyroid gland. The proximal portions of the common carotid, vertebral, and subclavian arteries run through Zone I as well. Zone II continues from the superior aspect of the cricoid cartilage to the angle of the mandible and includes the thyroid cartilage, vagus and recurrent laryngeal nerves, carotid and vertebral arteries, and the jugular veins. Zone III continues superiorly to the base of the skull and contains the distal aspects of the carotid and vertebral arteries, salivary and parotid glands, and cranial nerves IX to XII. The trachea and esophagus run from Zone I and II, with the pharynx in Zone III.6 Deep to the skin lie the superficial fascia and the subcutaneous tissue of the neck, which contains cutaneous nerves, superficial vessels, lymph nodes, and the platysma muscles. The deep cervical fascia contains multiple layers and is most notable for the investing fascia that surrounds all of the internal structures, including the carotid sheath.

Figure 3. Zones of the Neck |

|

|

Source: Getty Images |

Penetrating Throat Injuries

Any injury that violates the platysma muscles should be considered a penetrating neck injury.8 These occur mostly in cases of stab wounds, but may involve other sharp objects or gunshot wounds in accidental trauma or violence.17,18 Patients may present in a variety of ways depending on the extent of the penetration, size of the object that penetrated, and time of presentation to the ED since injury.18 All patients with penetrating neck injuries should be presumed to be critically ill until proven otherwise.

In a stable patient, it is appropriate to examine and explore the wound. However, this must be done with the utmost care so as to not advance any instruments through the platysma or iatrogenically violate the muscle layer.22 It is possible that if you probe past the platysma, you may cause further damage or disrupt hemostasis. If there is confidence that an injury to any part of the neck does not violate the platysma and the patient has not demonstrated any signs or symptoms of severe injury or decompensation, then the wound can be washed out gently with normal saline and closed in the typical fashion.8

Hard signs of significant injury include: airway compromise (i.e., deviated trachea, stridor, and dysphonia), air bubbling from a wound, an expanding or pulsatile hematoma, hematemesis, diminished or unequal upper extremity pulses, neurologic deficits, and massive subcutaneous emphysema.15,23,24 Patients with penetrating throat trauma leading to airway compromise should be intubated early. See Table 2 for stabilization techniques in these scenarios.

Table 2. Hard Signs of Penetrating Neck Injury and Stabilization |

|

|

Stabilization Technique |

Hard Signs of Significant Penetrating Neck Injury |

|

Emergent intubation by most experienced provider19 |

Airway compromise indicated by stridor, large hemoptysis or hematemesis, or expanding hematoma |

|

Emergent tracheostomy or cricothyrotomy19 |

Concern for larynx integrity in above scenario or unable to pass on two attempts |

|

Minimize BVM and positive pressure |

Subcutaneous emphysema, hematemesis, hemoptysis, wound bubbling air |

|

Place IV on contralateral side |

Distal extremity pulses unequal, consider dissection or transection |

|

Gentle insertion of 18-20 French Foley into wound track, inflate balloon to create tamponade, clamp Foley to prevent exsanguination17,20 |

Hemorrhaging/exsanguinating arterial wound |

|

Place in C collar |

Neurologic deficit or associated significant blunt injury to neck — note that there is a low incidence of concomitant cervical fracture in penetrating neck trauma, and most penetrating trauma leading to neurologic deficits is from carotid artery dissection22 |

|

Place in Trendelenburg position and apply direct venous pressure, consider balloon21 |

Persistent and significant oozing of venous blood |

|

BVM = bag valve mask ventilation; IV = intravenous |

|

Patients with more subtle findings, such as mild to moderate subcutaneous emphysema, dysphagia, dyspnea without hypoxia, non-pulsatile or non-expanding hematomas, mild venous oozing, minor hematemesis, and paresthesias without objective neurologic deficits, should still be evaluated thoroughly since these may be signs of significant injury.5

Often, it is difficult to predict what structures are damaged based purely on physical exam findings because these traumas frequently are associated with multiple injuries in different zones.22,24 (See Table 3.) While classic teaching has focused on evaluation of penetrating traumatic injuries by zone, recent studies have shown that this approach may miss other injuries because there is a poor correlation between the external wound and the internal injury.15 This is especially true for gunshot wounds in which trajectories are highly variable regardless of exit wound. The “non-zone” approach recommends clinical evaluation first with determination of “stable vs. unstable.”15 Unstable patients, or those with the aforementioned hard signs, should be stabilized with techniques discussed in Table 2. Management of penetrating neck wounds should follow the ABC algorithm: airway, breathing, and circulation. Once the airway is secured in the unstable patient, attention should be focused on controlling bleeding with direct pressure (when possible) or balloon tamponade.25 If these measures fail, the patient should be taken emergently to the operating room for surgical wound exploration.

Table 3. Classic Teaching of Penetrating Neck Injury by Zone5,8 |

|||

|

Zone |

Involved Structures |

Evaluation |

Consideration |

|

I (clavicles to inferior cricoid cartilage) |

Trachea, esophagus, vertebral/subclavian/carotid arteries, lung apices, thyroid cartilage, thoracic duct, thoracic outlet |

CTA, esophageal and tracheal evaluation (see text for more information) |

Difficult to evaluate surgically, high mortality due to difficulty of thoracic approach to bleeding |

|

II (superior cricoid cartilage to angle of mandible) |

Trachea, esophagus, vertebral/carotid arteries, jugular veins, larynx |

Mostly surgical evaluation |

If no hard signs, then evaluate as per Zone 1 |

|

III (angle of mandible to base of skull) |

Pharynx, vertebral and internal carotid arteries, jugular veins |

CTA |

Difficult to evaluate surgically |

|

CTA = computed tomography angiography |

|||

If the patient is stable or able to be stabilized and bleeding is controlled, obtain a CTA of the neck.26 CTA allows for characterization of the vasculature of the neck while also providing general information of the surrounding neck structures. If the penetrating object is identified on CTA, it should be left in place and removed only in the operating room, where subsequent bleeding can be surgically controlled.27 The controversy lies in the stable, asymptomatic patient without signs of significant injury but obvious violation of the platysma.28 In stable asymptomatic patients, monitoring for signs of airway or vascular injury is a reasonable alternative to CTA, which carries drawbacks of radiation, reactions to dye, and cost. The majority of stable patients with penetrating neck injuries will be admitted for observation and serial exams.

Blunt Trauma to the Throat

Blunt neck trauma ranges from minor bruising to devastating life-threatening injuries. These injuries may occur as a result of an assault, motor vehicle collision (MVC), sports, chiropractic manipulation, strangulation, clothesline injury, hanging, and falls. Given the high rate of morbidity and mortality associated with delayed or missed diagnosis of blunt neck injuries, it is important to have a high index of suspicion. Signs of severe injury requiring emergent intervention with airway stabilization and surgical exploration include those with tracheal deviation, neck bruising, venous distention, abnormal respiration, hypoxia, and subcutaneous emphysema.14 Although cervical spine injuries are beyond the scope of this article, it is critical to appreciate that blunt neck trauma often is associated with spinal injuries. As such, it is imperative to evaluate for these injuries (especially in the setting of hyperextension injuries in MVC or hangings) and maintain cervical spinal precautions throughout your evaluation.14,29,30

Airway or vascular compromise is the leading cause of early death. The leading cause of delayed death is missed esophageal injury.31 Although esophageal injury occurs in less than 10% of traumatic injuries, it is associated with high morbidity since the diagnosis often is delayed, leading to mediastinitis and its sequelae.32 Injuries to the esophagus can stem from penetrating trauma, direct blows, blast injuries, swallowed foreign bodies, or lacerations.7,33 Esophageal injuries may present with immediate dysphagia or chest pain, but more often they are clinically silent.7,33 In the setting of a stable patient, these injuries can be evaluated by a multitude of imaging techniques. A thoracic CT with intravenous contrast has high sensitivity for ruling out esophageal perforation when there is no visible mediastinal fluid collection, pneumomediastinum, nor esophageal wall defect.34,35 If any of these are present on CT, a water-soluble contrast esophagram is necessary to further evaluate for perforation and to determine where a rupture is located.33,34 This should be followed by endoscopy if there is any doubt or clinical inconsistency.33 Endoscopy and water-soluble contrast esophagram combined have a sensitivity close to 100%, whereas each individual sensitivity is around 80%.33

In an unstable patient, operative exploration of vascular or tracheal injury should be completed before evaluation of the esophageal injury. In this setting, anteroposterior and lateral X-rays of the neck may identify radiopaque foreign bodies (such as bullets), free-air, and soft tissue swelling suggestive of esophageal injury, which can be evaluated further and treated once the patient is stable.

In the setting of an ingested esophageal foreign body, a high index of suspicion should be maintained, even with negative plain films, because X-rays can miss radiolucent objects.36 If the foreign body is not seen, further imaging, including esophagogastroduodenoscopy, nasopharyngeal scope, CT, and ultrasound, should be considered. If a foreign body is missed, it may cause an esophageal hematoma or perforation, which may present with the classic triad of chest pain, odynophagia or dysphagia, and hematemesis.37 In regard to laryngotracheal injury, presenting symptoms often do not correlate with injury.23 Once the airway is secured, appropriate diagnosis of the extent of the injury can be evaluated with CT neck, fiberoptic laryngoscopy, and bronchoscopy.23

Blunt extracranial carotid injury (BECCI) also may occur in these scenarios, especially in instances of a hyperextension mechanism.38 Approximately 40% to 89% of BECCIs are from MVCs, 6% to 20% are from assault, and the remainder are from falls or hanging. In 30% of these cases, bilateral carotid injury is present.39 Injury occurs during extreme neck motion and subsequent shear forces on the vessel, laceration by bony fracture, or direct impact.39 These injuries have a high rate of neurologic sequelae, morbidity, and mortality, and should be worked up aggressively.

In patients with a seat belt sign (bruising to the neck, chest, and abdomen in the distribution of the seat belt of a vehicle), crepitus, or pain out of proportion to the exam, clinicians should have a low threshold for obtaining CTA. Additionally, high-force injuries, such as scapular fracture, sternal fracture, and first rib fracture, also should prompt CTA of the neck and chest. Alarmingly, some patients may be asymptomatic on presentation and develop neurologic symptoms from ischemia as far out as 31 days from injury.39 Patients with carotid dissection also can present with signs and symptoms of ipsilateral partial Horner’s syndrome characterized by ptosis, miosis, and anhidrosis.40,41 If the CTA is negative but there remains a high suspicion for injury based on the history and physical exam, a magnetic resonance angiography should be obtained.38

Airway Protection

Direct tracheal injury is more likely to be seen in penetrating injuries, but it certainly is possible in high-impact blunt injury.42 The airway should be secured immediately in the scenarios mentioned if a patient presents and/or develops stridor, respiratory distress, or evidence of shock or rapidly expanding hematoma. If the tracheal injury is very small and without loss of significant tissue, the provider can intubate orally or nasally with inflation of the balloon distal to the injury to prevent aspiration of blood.23 Tracheal transections have a high associated mortality and pose a challenge when securing the airway. If there is a high suspicion for tracheal transection, a primary cricothyroidotomy or tracheostomy should be performed. In addition, surgery should be consulted for tracheal repair.23

Patients with strangulation, hanging, and penetrating neck trauma mechanisms should be considered to have a difficult airway. Often, the associated injuries distort the anatomy and significantly compromise oxygenation and ventilation. These injuries may not be readily apparent on the initial assessment and, thus, a high index of suspicion is necessary to secure the airway early. The physician with the most airway experience should make the first attempt in these cases since repeat attempts lead to more edema, which increases the rate of failure.

Typically, direct laryngoscopy and rapid sequence intubation are preferred to video laryngoscopy because the video can become obscured by blood. However, a recent review article revealed similar success rates between the two modalities in bloody airways.43 If a physician is skilled with fiberoptics and the equipment is readily available, fiberoptic intubation may be preferred in the setting of distorted anatomy.

A surgical airway typically is the next step if intubation is unsuccessful. If endotracheal intubation is unsuccessful and a surgical airway is required, the provider should use caution and avoid cutting through traumatic hematomas. Given the complexity of these airways, surgical and consultant backup is recommended where available.

Case Conclusion

A 27-year-old intoxicated male presents via EMS after being assaulted with a baseball bat and sustaining significant facial trauma. Following the ABC algorithm, the primary concern is that the patient is showing signs of impending airway compromise with dysphagia, dysphonia, tracheal deviation, and non-pulsatile mass. Intubation should be completed by the most experienced airway provider. The neck should be marked and prepped for a surgical airway in the case that intubation is unsuccessful. Once the airway is secured, a thorough secondary exam should be completed. A CT of the head and neck should be obtained to evaluate for other head and neck injuries, given the extent of findings on his exam.

REFERENCES

- Farmer B, Klovenski V. Tongue laceration. In: StatPearls [Internet]. 2020.

- Badeau A, Lahham S, Osborn M. Management of complex facial lacerations in the emergency department. Clin Pract Cases Emerg Med 2017;1:162-165.

- Abdulaziz A, Tainter C. Emergency department pain management: Beyond opioids. Emerg Med Pract 2019;21:11.

- Katsetos SL, Nagurka R, Caffrey J, et al. Antibiotic prophylaxis for oral lacerations: Our emergency department’s experience. Int J Emerg Med 2016;9:24.

- Tintinalli J, Stapczynski JS, Ma OJ, et al. Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide. 9th ed. McGraw-Hill; 2018.

- Yadav AK, Jaisani MR, Pradhan L, et al. Animal inflicted maxillofacial injuries: Treatment modalities and our experience. J Maxillofac Oral Surg 2017;16:356-364.

- Li J. Emergency department management of dental trauma: Recommendations for improved outcomes in pediatric patients. Pediatr Emerg Med Pract 2018;15:8.

- Walls RM, Hockberger RS, Gausche-Hill, M. Rosen’s Emergency Medicine: Concepts and Clinical Practice. 9th ed. Elsevier; 2018.

- Duchicela S, Lim A. Pediatric nerve blocks: An evidence-based approach. Pediatr Emerg Med Pract 2013;10:10.

- Kretlow JD, McKnight AJ, Izaddoost SA. Facial soft tissue trauma. Semin Plast Surg 2010;24:348-356.

- Smith A, Ray M, Chaiet S. Primary palate trauma in patients presenting to US emergency departments, 2006-2010. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2018;144:244-251.

- Lacey L, Dabbas N, Saker R, Blakeley C. Dissection of the carotid artery as a cause of fatal airway obstruction. Emerg Med J 2007;24:367-368.

- Barron BJ, Scott J, Abbey-Mensah GN. Current topics in emergency trauma care: Part 1: Limiting radiation exposure in trauma imaging. Emerg Med Pract 2020;22(Suppl 8):1-21.

- Henry M, Hern HG. Traumatic injuries of the ear, nose and throat. Emerg Med Clin North Am 2019;37:131-136.

- Madsen AS, Bruce JL, Oosthuizen GV, et al. Correlation between the level of the external wound and the internal injury in penetrating neck injury does not favour an initial zone management approach. BJS Open 2020;4:704-713.

- Yu M, Wang SM. Anatomy, head and neck, zygomatic. In: StatPearls [Internet]. 2020.

- Navsaria P, Thoma M, Nicol A. Foley catheter balloon tamponade for life-threatening hemorrhage in penetrating neck trauma. World J Surg 2006;30:1265-1268.

- Nickson C. Airway in neck trauma. Life in the Fast Lane. March 2019. https://litfl.com/airway-in-neck-trauma/

- Advanced Trauma Life Support. 10th ed. American College of Surgeons; 2018.

- Jose A, Arya S, Nagori SA, Thukral H. Management of life-threatening hemorrhage from maxillofacial firearm injuries using Foley catheter balloon tamponade. Craniomaxillofac Trauma Reconstr 2019;12:301-304.

- Ball CG. Penetrating nontorso trauma: The head and the neck. Can J Surg 2015;58:284-285.

- Roepke C, Benjamin E, Jhun P, Herbert M. Penetrating neck injury: What’s in and what’s out? Ann Emerg Med 2016;67:578-580.

- Moonsamy P, Sachdeva UM, Morse CR. Management of laryngotracheal trauma. Ann Cardiothorac Surg 2018;7:210-216.

- Santiago-Rosado LM, Sigmon DF, Lewison CS. Tracheal trauma. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; July 10, 2020.

- Ball CG, Wyrzykowski AD, Nicholas JM, et al. A decade’s experience with balloon catheter tamponade for the emergency control of hemorrhage. J Trauma 2011;70:330-333.

- McCrary HC, Nielsen TJ, Goldstein SA. Penetrating neck trauma: An unusual case presentation and review of the literature. Ann Oto Rhinol Laryngol 2016;125:682-686.

- Abdelmasih M, Kayssi A, Roche-Nagle G. Penetrating paediatric neck trauma. BMJ Case Rep 2019;12:e226436.

- Madsen AS, Kong VY, Oosthuizen GV, et al. Computed tomography angiography is the definitive vascular imaging modality for penetrating neck injury: A South African experience. Scand J Surg 2018;107:23-30.

- Buitendag JJP, Ras A, Kong VY, et al. Hanging-related injury in Pietermaritzburg, South Africa. S Afr Med J 2020;110:400-402.

- Zátopková L, Janík M, Urbanová P, et al. Laryngohyoid fractures in suicidal hanging: A prospective autopsy study with an updated review and critical appraisal. Forensic Sci Int 2018;290:70-84.

- Mubang RN, Sigmon DF, Stawicki SP. Esophageal trauma. In: StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; April 27, 2020.

- Petrone P, Kassimi K, Jiménez-Gómez M, et al. Management of esophageal injuries secondary to trauma. Injury 2017;48:1735-1742.

- Lee NH, Ahn HY, Lee CS. Successful treatment of delayed esophageal perforation caused by air-blast trauma. Asian J Surg 2020;43:1026-1028.

- Awais M, Qamar S, Rehman A, et al. Accuracy of CT chest without oral contrast for ruling out esophageal perforation using fluoroscopic esophagography as reference standard: A retrospective study. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg 2019;45:517-525.

- Fuhrmann C, Weissenborn M, Salman S. Mediastinal fluid as a predictor for esophageal perforation as the cause of pneumomediastinum. Emerg Radiol 2020;10:1007.

- Luo CM, Lee YC. Diagnostic accuracy of lateral neck radiography for esophageal foreign bodies in adults. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2020;215:465-471.

- Sharma A, Hoilat GJ, Ahmad SA. Esophageal hematoma. In: StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; June 23, 2020.

- Kibayashi K, Shimada R, Nakao KI. Delayed death due to traumatic dissection of the common carotid artery after attempted suicide by hanging. Med Sci Law 2019;59:17-19.

- Lee TS, Ducic Y, Gordin E, Stroman D. Management of carotid artery trauma. Craniomaxillofac Trauma Reconstr 2014;7:175-189.

- Go S. Stroke syndromes. In: Tintinalli JE, Ma OJ, Yealy DM, et al, eds. Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide. 9th ed. McGraw-Hill Education; 2020:1119-1136.

- Kasravi N, Leung A, Silver I, Burneo JG. Dissection of the internal carotid artery causing Horner syndrome and palsy of cranial nerve XII. CMAJ 2010;182:E373-E377.

- Dumanlı A, Gencer A, User NN, et al. Total cervical tracheal rupture following blunt trauma. Tuberk Toraks 2018;66:345-348.

- Carlson JN, Crofts J, Walls RM, Brown CA 3rd. Direct versus video laryngoscopy for intubating adult patients with gastrointestinal bleeding. West J Emerg Med 2015;16:1052

Trauma to the mouth and throat is very common. Fortunately, the majority of the injuries are minor, but early and timely recognition of critical, potentially devastating injuries is essential. The authors provide a thorough review highlighting critical injuries and their management.

Subscribe Now for Access

You have reached your article limit for the month. We hope you found our articles both enjoyable and insightful. For information on new subscriptions, product trials, alternative billing arrangements or group and site discounts please call 800-688-2421. We look forward to having you as a long-term member of the Relias Media community.