AUTHORS

Tiffany Murano, MD, Associate Professor, Department of Emergency Medicine, Rutgers New Jersey Medical School, Newark

Lana Shaker, MD, Resident Physician, Department of Emergency Medicine, Rutgers New Jersey Medical School, Newark

PEER REVIEWER

Catherine A. Marco, MD, FACEP, Professor, Emergency Medicine and Surgery, Wright State University, Dayton, OH

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

- Ectopic pregnancy is a pregnancy that implants outside the endometrial cavity. Heterotopic pregnancy, seen most often in women undergoing assisted reproductive technology, is the coexistence of an intrauterine pregnancy and an ectopic pregnancy.

- Risk factors for ectopic pregnancy include a history of chlamydial or gonorrheal infection, exposure to diethylstilbestrol, intrauterine device use, and assisted reproductive technology. However, 50% of women with an ectopic pregnancy do not have a risk factor.

- The most common presentation is first trimester bleeding and abdominal pain. A ruptured ectopic pregnancy may cause a massive hemorrhage requiring surgery. Ultrasound can demonstrate an empty uterus suggesting an ectopic pregnancy, but the definite diagnosis can be made only if the ectopic pregnancy is found on ultrasound.

- For gestations greater than 5.5 weeks, a transvaginal ultrasound exam should identify an intrauterine pregnancy with nearly 100% accuracy. However, a heterotopic pregnancy is still possible.

An ectopic pregnancy is a pregnancy that implants outside the endometrial cavity. It has significant health consequences and is an important cause of morbidity and mortality for reproductive-age women.1 These women are at risk for complications, such as organ rupture with massive bleeding, risks related to treatment, recurrent ectopic pregnancy, and future infertility.1 Making the diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy is critical to reduce morbidity and mortality associated with this condition.2 Ectopic pregnancy has a misdiagnosis rate of 21% in women with a tubal ectopic pregnancy and severe abdominal hemorrhage.3

Ectopic pregnancy is a consideration in the workup of the first trimester pregnant patient who has received assisted reproductive technology (ART) treatment and presents to the emergency department (ED).4 Heterotopic pregnancy, which is defined as the presence of simultaneous gestations inside and outside of the uterine cavity, is historically rare.4 However, as infertility treatments are used more widely, the incidence of heterotopic pregnancies has increased.4 Because of the presence of a concurrent intrauterine gestation, there may be a delay in the diagnosis of the ectopic gestation in a heterotopic pregnancy, leading to increased risk of tubal rupture, hypovolemic shock, requirement of a blood transfusion, and maternal mortality.5

Epidemiology

Incidence of Ectopic Pregnancy

The incidence of ectopic pregnancy in pregnant women is approximately 2% in the United States.6-8 Although there have been improvements in diagnosis and management, ectopic pregnancy is the leading cause of maternal death in the first trimester of pregnancy and accounts for up to 9% of all pregnancy-related deaths.6-10 The overall rate of tubal ectopic pregnancy decreased 5% annually between 1998 and 2011 in the inpatient setting, which may represent a true decrease in ectopic pregnancy occurrence or an increase in outpatient management of ectopic pregnancy.11 The prevalence of ectopic pregnancy among women who present to the ED with first trimester vaginal bleeding or abdominal pain is significantly higher, with reports citing prevalence as high as 18%.7 The incidence of ectopic pregnancy after in vitro fertilization (IVF) is reported to be less than 5%, but it can be as high as 11% in patients with tubal factor infertility.12 Up to one-third of women are treated after the ectopic pregnancy has ruptured, and 6-10% of patients with rupture present with hemodynamic instability.3

Mortality Rates

The overall ectopic pregnancy mortality rate declined by approximately 56% from 1980 to 2007 to a five-year national average of 0.50 per 100,000 live births.1 Although the overall trend in mortality has been downward, age and racial disparities persist. The ectopic pregnancy mortality ratio is reported to be 6.8 times higher for African Americans than for Caucasians and 3.5 times higher for women older than 35 years of age, without adjustment for other factors such as comorbid conditions.1 Based on 1998-2007 data, two-thirds of all ectopic pregnancy deaths in the United States occurred in the ED, in transit to a hospital, or outside the hospital.1

Risk Factors

The risk factors for ectopic pregnancy include a history of pelvic inflammatory disease, previous tubal surgery, and previous ectopic pregnancy.13 (See Table 1.) The chance of a recurrence in a woman with a history of one ectopic pregnancy is about 10% and increases to 25% if she has a history of multiple ectopic pregnancies.7 Women with a history of chlamydial and/or gonorrheal infection have increased risk of ectopic pregnancy, likely due to tubal infertility factor.14

Table 1. Risk Factors for Ectopic Pregnancy6 |

|

Diethylstilbestrol (DES) is a synthetic estrogen that was given to pregnant women.15 Women who had in utero DES exposure may have structural reproductive tract anomalies, an increased infertility rate, and a higher risk of ectopic pregnancy, as well as of spontaneous abortion and preterm delivery.15

Women who use an intrauterine device (IUD) have a lower overall risk of ectopic pregnancy than women who do not use contraception because IUDs are highly effective for pregnancy prevention. However, up to 53% of pregnancies that occur with an IUD in place are ectopic.7,16,17 IUD use reached more than 100 million women worldwide by 2015 and represents a risk factor for an extrauterine pregnancy, reinforcing the importance of high clinical suspicion in reproductive-age women despite highly effective contraception use.17

The following factors have not been associated with an increased risk of ectopic pregnancy: oral contraceptive use, emergency contraception failure, previous elective pregnancy termination, pregnancy loss, and cesarean delivery.7

Half of all women who are diagnosed with ectopic pregnancy do not have any identifiable risk factors.3 Therefore, the lack of risk factors should not lower the clinician’s index of suspicion, because this may lead to delays in diagnosis or misdiagnosis. Women with a prior normal pregnancy and no history of a prior ectopic pregnancy specifically have a higher incidence of rupture, likely because of decreased suspicion of ectopic pregnancy and subsequent delay in diagnosis of these patients.18

Women who have a history of infertility are at higher risk for ectopic pregnancy.7 Specifically, with IVF, the transfer of more than one embryo increases the risk for potential multiple embryo implantations in the uterus as well as elsewhere.5 Additionally, many women who undergo ART have tubal pathology, which increases the risk of ectopic pregnancy in natural and assisted conceptions.5

Pathophysiology

An ectopic pregnancy occurs when a fertilized ovum implants in a location outside of the endometrial cavity.6,19 Damage to the fallopian tube mucosa associated with sexually transmitted infections is a major cause of ectopic pregnancy. Chlamydia trachomatis infection causes changes in cell adhesion molecules in the fallopian tubes that increase embryo implantation.20

If an ectopic pregnancy is undiagnosed and/or untreated, it may result in one of the following possibilities: expulsion into the abdominal cavity (rare), continued growth, or spontaneous reabsorption. If it is expelled into the abdominal cavity, it can be reabsorbed or continue to grow within the abdominal cavity. Ectopic pregnancies that continue to grow (whether in the original location, such as a tubal pregnancy, or after expulsion into the abdominal cavity) can lead to organ rupture and massive intraperitoneal hemorrhage.

Location

More than 90% of ectopic pregnancies occur in the fallopian tube.7 The most common implantation location is the ampulla, followed by the isthmus of the tube, and then the fimbria.21 The ovary comprises approximately 3% of all ectopic pregnancies.21 Interstitial and cornual locations account for 1-6% of all ectopic pregnancies.21 Abdominal pregnancy occurs as a result of implantation in the peritoneal cavity, outside of the uterus, the ovaries, and the fallopian tubes. Commonly, this is the result of tubal abortion and reimplantation into the abdominal cavity, with the broad ligament being the most common site.21 The cervix accounts for < 1% of all ectopic pregnancies, but this figure can be higher in ART conceptions.21,22

Previous uterine surgery also may lead to defects in the myometrium that can facilitate intramural implantation.23 Cesarean delivery scar pregnancies are thought to occur in 1 in 1,800 pregnancies and comprise 6% of ectopic pregnancies in women with a prior cesarean delivery.21 IVF and embryo transfer in women with a history of cesarean delivery increase the risk of cesarean scar pregnancy.24 Cesarean scar pregnancy can lead to uterine rupture if it is not diagnosed correctly and treated expeditiously.24

Pregnancy of Unknown Location

The term “pregnancy of unknown location” (PUL) refers to a positive pregnancy test with no clear intrauterine or ectopic pregnancy shown on transvaginal ultrasonography (TVUS).7 This state can be challenging diagnostically because the increase in beta-human chorionic gonadotropin (beta-hCG) level can be similar in women with an early viable pregnancy, ectopic pregnancy, or early pregnancy loss.13 Seven percent to 20% of women identified with PUL will be diagnosed subsequently with an ectopic pregnancy.21 The following three situations are possible when an intrauterine pregnancy (IUP) is not seen on ultrasound:

- An ectopic pregnancy;

- An IUP that is too early for ultrasound detection;

- An IUP that is abnormal.

Clinical Features

The most common presenting symptoms of a non-ruptured ectopic pregnancy are first trimester bleeding and abdominal pain.6 The classic triad that is described is a missed menstrual period, abdominal pain, and vaginal bleeding. However, only about 50% of ectopic pregnancies present with all three symptoms.25

Physical exam findings of hypotension, tachycardia, moderate to severe abdominal or pelvic tenderness that is specifically lateral, and/or peritoneal signs such as rebound tenderness and guarding indicate rupture.26 It is important to note that vital signs have not been found to correlate with the degree of hemoperitoneum and may be normal in the setting of ruptured ectopic pregnancy.27

Differential Diagnosis

Vaginal bleeding and abdominal pain also can occur with IUP, spontaneous abortion, or in nonpregnant women. (See Table 2.)

Table 2. Differential Diagnosis of Acute Abdominal Pain in Early Pregnancy |

|

Obstetric and Gynecologic Causes

Nonobstetric Causes

|

Abdominal Pain

Acute abdominal pain in pregnancy can be caused by obstetric as well as nonobstetric etiologies. Therefore, physicians should maintain a high index of suspicion for nonobstetric causes. For instance, the physiologic changes of pregnancy can increase the risk of an acute abdomen.28 In addition, the diagnosis of acute abdominal pathology may be limited, missed, or delayed because of the reluctance of providers to use X-ray or computer tomography (CT) scan in pregnant patients.

Moreover, pregnancy may exacerbate nonobstetric etiologies of abdominal pain. For example, hormonal variations can delay gastric emptying, increase intestinal transit time, and cause gastro-esophageal reflux, abdominal bloating, constipation, nausea, and vomiting in up to 80% of pregnant females.28

Nonobstetric causes of abdominal pain that must be considered include appendicitis, cholecystitis, biliary colic, pancreatitis, peptic ulcer, urolithiasis, intestinal obstruction, inflammatory bowel disease, ruptured aneurysm, and trauma. The most common nonobstetric surgical emergency during pregnancy is acute appendicitis, followed by cholecystitis.28 Leukocytosis may be physiologic, but a left shift or the presence of bands indicates an underlying inflammation.28

Elevated serum cholesterol and lipid levels, decreased gallbladder motility and emptying, and insoluble bile acid accumulation in pregnancy can predispose the patient to the formation of gallstones.28 The clinical features of acute cholecystitis are similar to those in nonpregnant adults. Ultrasonography is the diagnostic study of choice.

Obstetric causes of acute abdominal pain can be physiologic or pathologic. One physiologic etiology is pain caused by stretching of the round ligament. Round ligament pain occurs more commonly in multiparous women, complicates up to 30% of pregnancies, and typically occurs during the end of the first trimester.28 Typically, the pain is cramp-like, is localized in the lower quadrants, and radiates to the groin.28

Uterine and ovarian torsion, molar pregnancy, ovarian cyst, and degenerating uterine fibroids also are in the differential diagnosis. In the setting of trauma, uterine rupture must be considered.28

Vaginal Bleeding

Twenty-five percent of pregnant women experience vaginal bleeding before 12 weeks’ gestation.6 Bleeding equal to or heavier than normal menstruation and accompanied by pain is associated with an increased risk of an abnormal pregnancy.6 Nonobstetric causes include cervicitis, uterine fibroids, trauma, cervical cancer, polyps, and dysfunctional uterine bleeding.29 Obstetric causes include bleeding in a viable IUP, early pregnancy loss, subchorionic hemorrhage, and ectopic pregnancy.

Diagnosis

An evaluation for pregnancy is part of the initial examination for any woman of childbearing age who presents to the ED with abnormal vaginal bleeding or abdominal pain. If the woman is known to be pregnant, the menstrual history and prior ultrasonography can help to establish gestational age as well as the pregnancy location. Severe bleeding and/or abnormal vital signs should shift the initial focus to hemodynamic stability and resuscitation.

Physical Examination

Some providers have begun to question the utility of routine pelvic examinations in patients who present with first trimester bleeding and abdominal pain. One recent study supported the safety of omitting pelvic examinations in women with a confirmed intrauterine pregnancy on ultrasound unless specific clinical concerns are present.30 Speculum examination may assist with identification of nonobstetric causes of bleeding, such as vaginitis, cervicitis, decidual cast, or cervical polyp. Products of conception that are visible on speculum examination indicate an incomplete abortion.13 The pelvic examination also may include a way for the clinician to quantify how much bleeding is occurring and to determine whether the cervical os is open or closed. In a pregnant patient, abdominal pain with peritoneal signs should prompt immediate evaluation by an obstetrics and gynecology (OB/GYN) specialist.

Serum Beta-hCG

Beta-hCG can be detected in the plasma of a pregnant woman as early as eight days after ovulation.31,32 Serial beta-hCG concentration measurements are used to distinguish normal from abnormal pregnancies. In early pregnancy, serum beta-hCG levels increase in a curvilinear pattern until they peak at approximately 100,000 mIU/mL at 10 weeks’ gestation.7 Beta-hCG typically will plateau or decrease by 10 weeks’ gestation.13 In almost 99% of viable first trimester IUPs, beta-hCG values increase by at least 53% every 48 hours.6,22

Ectopic pregnancy, viability of pregnancy, or location of a gestation cannot be diagnosed by a single serum beta-hCG value.7 TVUS demonstrates an intrauterine gestational sac with nearly 100% sensitivity at beta-hCG levels of 1,500 to 2,000 mIU/mL.13,31,33 If the beta-hCG level is greater than this cutoff and a gestational sac is not visible, ectopic pregnancy is likely.29 Although failure of the beta-hCG level to increase at an appropriate rate can suggest an abnormal pregnancy, such as an ectopic or a nonviable IUP, 1% of patients with a viable IUP will have a slower rate of increase, and 21% of ectopic pregnancies will have beta-hCG level increasing appropriately.6 Therefore, when monitoring the trend in beta-hCG levels, an increase of ≥ 66% in 48 hours is indicative of a viable IUP.22

Atypical beta-hCG measurement also may occur with twin gestations or heterotopic conception with one conceptus failing. In this instance, there may be a higher than expected beta-hCG before the failure of one conceptus, followed by a lag in the normally expected increase rate, and then resumption of a normal increase.34 Decreasing beta-hCG values in the first trimester indicate a failing pregnancy and may be used to monitor spontaneous resolution.7 Rupture of an ectopic pregnancy can occur at any beta-hCG level, including low or declining beta-hCG or both.35,36 Accurate gestational age calculation is the best determinant of when a normal pregnancy should be seen on TVUS.7 The uncertainty of a single serum beta-hCG measurement and its correlation to findings on ultrasound and pregnancy status highlights the importance of considering all available data when determining the pregnancy location.

Discriminatory Zone

The discriminatory zone is the beta-hCG range at which an IUP should be seen on TVUS, with sensitivity approaching 100% at the upper level.9 The concept originally was established using abdominal ultrasonography but now is widely accepted using TVUS. The discriminatory zone can vary with the type of ultrasound machine used, the sonographer, the body habitus of the patient, the presence of uterine fibroids, the degree of ovarian pathology, and the number of gestations.6,21 As beta-hCG increases, the specificity of ultrasonography also increases; however, cases of viable IUPs not detected by ultrasonography have been reported with beta-hCG levels up to 4,300 mIU/mL.6 A discriminatory zone of 1,500 to 3,000 mIU/mL is used most commonly.6,9,29 Each institution should set the discriminatory cutoff based on that hospital’s success in identifying intrauterine pregnancies correctly. Some clinicians may choose a low cutoff of 1,500 mIU/mL, which would have a high sensitivity but at the cost of low specificity. This would increase the possibility of incorrectly classifying a developing IUP as an abnormal gestation. Alternatively, some clinicians may choose a higher cutoff of 3,500 mIU/mL.7 This may provide reassurance in correctly diagnosing an early viable gestation but may delay the diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy, decreasing the sensitivity.9

Other Laboratory Testing

A baseline hemoglobin and Rhesus (Rh) factor testing should be obtained for all patients with suspected ectopic pregnancy.13 Patients being considered for medical management of ectopic pregnancy should have screening labs with complete blood count, serum creatinine level, and liver and kidney function tests to evaluate for contraindications to methotrexate administration.6

Initial progesterone measurement as a predictor for treatment failure of methotrexate administration has failed to demonstrate prognostic significance, and testing is not recommended at this time.9,37

Transvaginal Ultrasonography

TVUS is the method of choice for visualizing a pregnancy.2,38 When used by emergency physicians in the diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy, bedside TVUS provides sensitivity and negative predictive values of > 99%.39

For gestations greater than 5.5 weeks, a TVUS examination should identify an IUP with near 100% accuracy.9 The first sign of an IUP is a small sac located eccentrically within the decidua. This will evolve into a double decidual sign, which appears as two rings of tissue around the sac, followed by a yolk sac becoming visible around the fifth week on TVUS.2 (See Table 3.)

Table 3. Early Pregnancy Ultrasound Findings2,29,45 |

|||

|

Gestational Sac |

Yolk Sac |

Embryo |

|

|

Normal early pregnancy |

Appears 4-5 weeks after LMP |

Appears 5-6 weeks after LMP, when diameter of GS is > 10 mm |

Appears ~6 weeks after LMP when diameter of GS is > 18 mm, with cardiac activity appearing 6.5 weeks after LMP when embryonic CRL is > 5 mm |

|

Suspicious for early pregnancy loss |

Mean GS diameter of 16-24 mm and no embryo visualized; absence of embryo with cardiac activity 7-13 days after US shows GS but no YS |

Absence of embryo with cardiac activity 10 days after US shows GS and YS |

CRL < 7 mm and no embryonic cardiac activity; absence of embryo > 6 weeks after LMP; embryo heart rate < 85 beats per minute |

|

Diagnostic for early pregnancy loss |

Mean GS diameter is > 25 mm and no embryo visualized; absence of embryo with cardiac activity > 2 weeks after US with GS without YS |

Absence of embryo with cardiac activity > 11 days after US with GS and YS |

CRL > 7 mm and no embryo cardiac activity |

|

CRL = crown-rump length; GS = gestational sac; LMP = last menstrual period; US = ultrasonography; YS = yolk sac |

|||

A yolk sac should be visualized when the gestational sac is greater than 10 mm in diameter.29 The presence of a yolk sac on ultrasound is the first non-controversial finding of an IUP.29 (See Figure 1.) An embryonic pole appears at approximately six weeks.2 When the embryo exceeds 5 mm in length, cardiac activity should be present.29 (See Figure 2.) An IUP can be confirmed absolutely by the presence of an intrauterine sac with an embryo that has a detectable heartbeat.2 (See Figure 3.) The crown-rump length is the most accurate way to date an early pregnancy.29 A normal gestational sac or embryo should grow at the rate of 1 mm per day.29

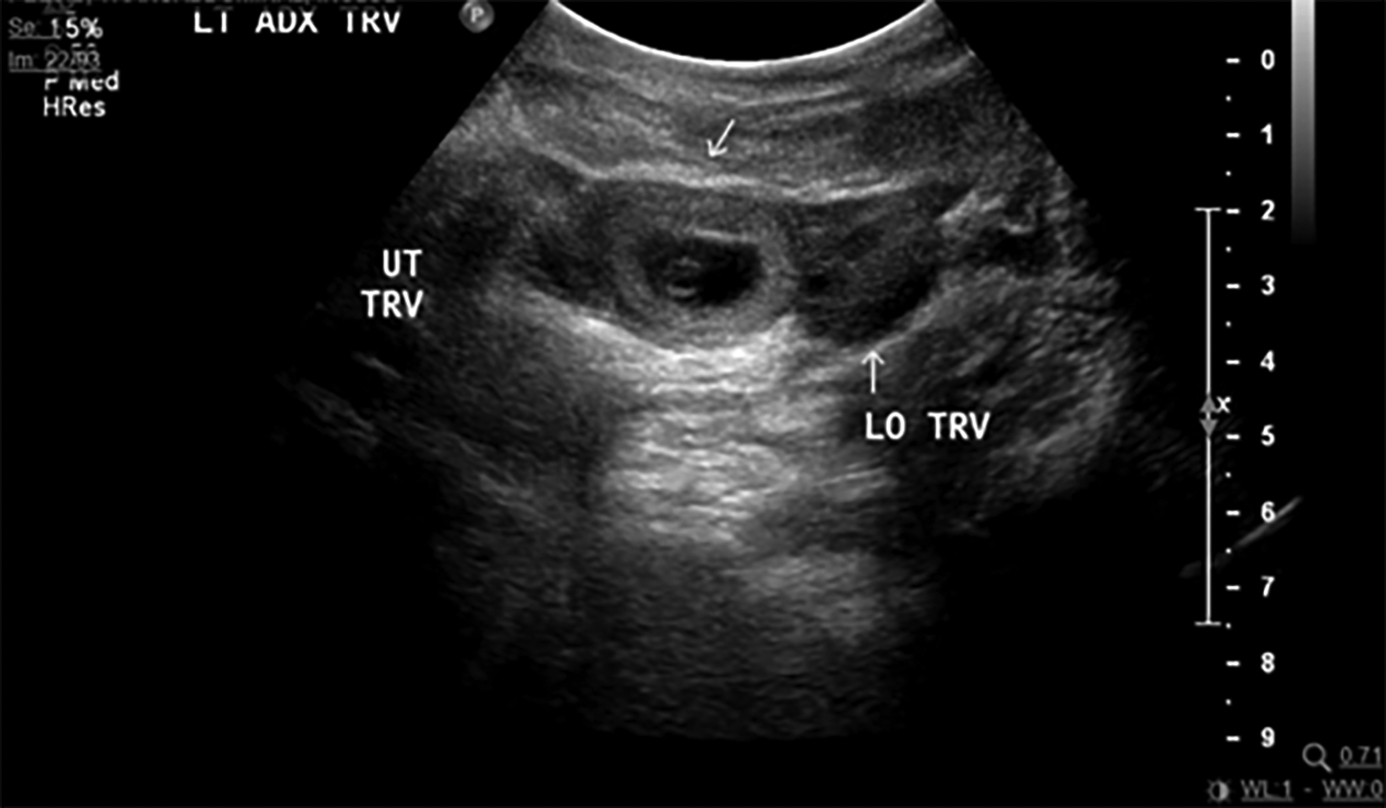

Figure 1. Intrauterine Gestational Sac With a Yolk Sac (White Arrow) |

|

|

Image courtesy of Dr. Basil Hubbi. |

Figure 2. Intrauterine Pregnancy |

|

|

Transvaginal ultrasound image depicting an intrauterine pregnancy. There is a gestational sac containing a yolk sac and a fetal pole (white arrow). Image courtesy of Dr. Basil Hubbi. |

Figure 3. Intrauterine Pregnancy |

|

|

Transvaginal ultrasound image depicting an intrauterine pregnancy with a fetal heart rate of 163 beats per minute detected in M-mode. Image courtesy of Dr. Basil Hubbi. |

TVUS is recommended over transabdominal ultrasonography for suspected ectopic pregnancy because of superior visualization of an ectopic mass.6 Transabdominal scanning is less sensitive and will show the typical landmarks of an IUP approximately a week after they are visible on TVUS.29 The most common finding in tubal ectopic pregnancies is visualization of a mass with a hyperechoic ring in the adnexa which moves separate from the ovary.21 To look for the “sliding organ sign,” apply pressure with the tip of the endocavitary ultrasound probe to see the sliding of the cervix, the uterine fundus, and the ovaries relative to the pelvic wall or intestines.40 A negative sliding organ sign is seen with ectopic pregnancies in the cervix, cesarean delivery scar, and ovary.41 An embryo with cardiac activity outside the uterus is diagnostic of an ectopic pregnancy.29 Other signs suggestive of an ectopic pregnancy include a complex adnexal mass and cul-de-sac fluid.13 Anechoic or echogenic free fluid visualized within the pouch of Douglas or Morison’s pouch suggests hemoperitoneum secondary to rupture. However, this is not diagnostic of ectopic pregnancy and is seen with other conditions, such as rupture of an ovarian cyst.21

In ectopic pregnancy, the uterine cavity often is described as “empty” on ultrasound, but in some cases it has a collection of fluid within the endometrial cavity, referred to as a “pseudosac.”21 The pseudosac occurs from bleeding of the decidualized endometrium when an extrauterine gestation is present. The pseudosac is distinguished by its central location, filling the endometrial cavity.9 Figure 4 shows an ectopic pregnancy as a complex mass in the adnexa or as a gestational sac containing a yolk sac and/or a fetal pole. Figure 5 shows an ectopic pregnancy with a fetal heartbeat. (See Table 4.)

Figure 4. Ectopic Pregnancy in Left Adnexa |

|

|

Transvaginal ultrasound of an ectopic pregnancy in the left adnexa. Indicated in the image is the uterus in transverse view (UT TRV) and the left ovary (LO). There is a gestational sac in the left adnexa with a yolk sac (white arrow). Image courtesy of Dr. Basil Hubbi. |

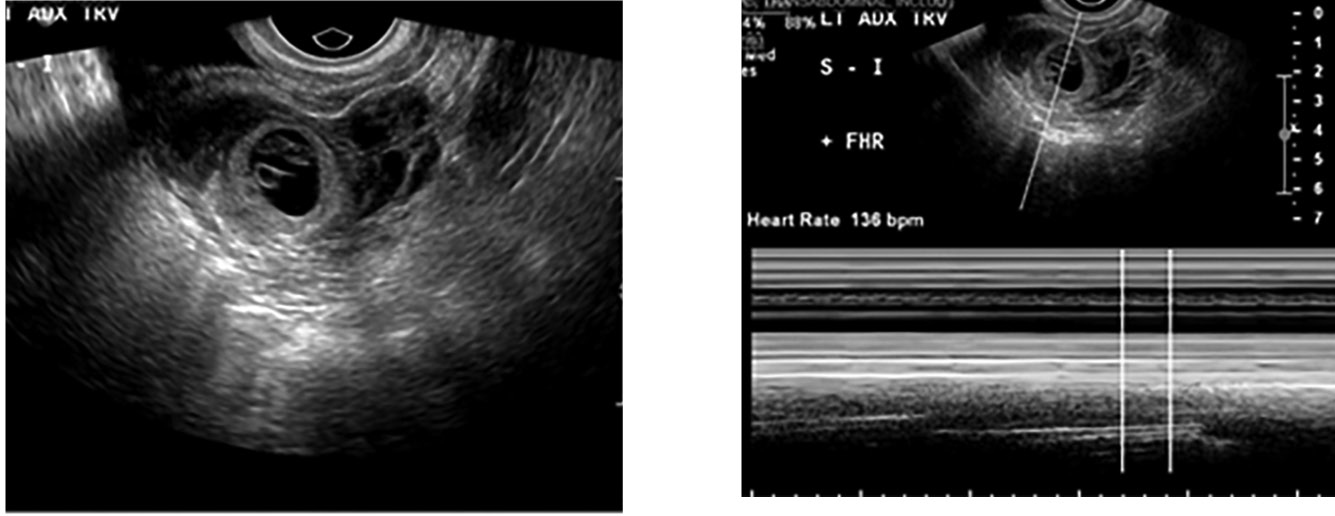

Figure 5. Ectopic Pregnancy With Fetal Pole |

|

|

Transvaginal ultrasound depicting an ectopic pregnancy in the left adnexa. There is a fetal pole that has a heart rate of 136 beats per minute seen in M-Mode (image on right). Images courtesy of Dr. Basil Hubbi. |

Table 4. Sonographic Criteria of Ectopic Pregnancy Locations |

|

|

Type of Ectopic Pregnancy |

Sonographic Criteria21 |

|

Tubal |

|

|

Interstitial |

|

|

Cornual |

|

|

Cervical |

|

|

Cesarean Delivery Scar |

|

|

Ovarian |

|

|

Abdominal |

|

Even if an IUP is identified, there is still a very small chance that the patient has a heterotopic pregnancy. In a heterotopic pregnancy, an adnexal mass may be seen but may be mistaken for a hemorrhagic corpus luteum or ovarian cyst, especially in hyperstimulated ovaries.4 Figure 6 shows a heterotopic pregnancy visualized on TVUS.42 The heterotopic pregnancy may go unnoticed in the setting of an IUP. Other suggestions of a heterotopic pregnancy include signs and symptoms of an ectopic pregnancy, beta-hCG levels higher for the period of gestation with an IUP, hemoperitoneum, hematosalpinx, and free fluid in the peritoneum, pelvis, or pouch of Douglas.4

Figure 6. Heterotopic Pregnancies |

|

|

Transvaginal ultrasound showing heterotopic pregnancies. The intrauterine pregnancy is seen on the right side of the image with a horizontal arrow pointing to the fetal pole. The ectopic pregnancy is visualized as a sac-like structure in the right cornua of the uterus (indicated by the vertical arrow). Image courtesy of Dr. Basil Hubbi. |

Management

Resuscitate any hemodynamically unstable patients and obtain emergent consultation.

Surgical Management

Surgical management is indicated for patients who are hemodynamically unstable, have contraindications to medical treatment, or have failed medical treatment. Cardiovascular instability, intra-abdominal bleeding, significant pain or peritoneal signs, or evidence of moderate to large hemoperitoneum on ultrasound indicates rupture, necessitating surgical management.2,13 Laparoscopy is the preferred approach for surgical management because of decreased surgical blood loss, amount of analgesic used, cost, and shorter hospital length of stay.9 Laparotomy is reserved for patients who are hemodynamically unstable, have extensive intraperitoneal bleeding, or have poor visualization of the pelvis during laparoscopy.6

Medical Management

Methotrexate (MTX) is a folic acid antagonist that inhibits DNA synthesis and cell replication, selectively killing rapidly dividing cells.9 Because of its effect on highly proliferative tissues, MTX has a strong dose-related potential for toxicity.43 Medical management with MTX is safe and effective in carefully selected patients. MTX use in the treatment of ectopic pregnancy is off label and has not been licensed or approved for this use by the Food and Drug Administration. Tables 5 and 6 highlight the criteria to consider during patient selection for medical management. MTX should be avoided in patients with significant elevations in serum creatinine, liver transaminases, or bone marrow dysfunction indicated by significant anemia, leukopenia, or thrombocytopenia.7 Because of its adverse effect on rapidly dividing tissues, MTX should not be given to women with active gastrointestinal or respiratory disease.7 Adverse effects include nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, stomatitis, conjunctivitis, impaired liver function, bone marrow depression, and photosensitivity.6,43

Table 5. Criteria for Management of Ectopic Pregnancy6,22,29,44 |

||

|

Expectant Management |

Medical Management |

Surgical Management |

|

|

|

Table 6. Patient Contraindications to Methotrexate Treatment (Absolute Contraindications) |

|

Before administering MTX, it is important to reasonably exclude the presence of an IUP. Most physicians prefer to consult with obstetric specialists.7 Relative contraindications to MTX include embryonic cardiac activity detected by TVUS, high initial beta-hCG, ectopic pregnancy > 4 cm in size on TVUS, and refusal to accept blood transfusion.7 MTX is used for ectopic pregnancies located outside the fallopian tube, such as cervical, interstitial, ovarian, and abdominal gestations, and often is a first-line treatment because of the difficulty and risk of surgical resection.9

There are different treatment protocols, but the single-dose regimen is the most common.22 Since there is significant commitment to follow-up with OB/GYN specialists for serial beta-hCG levels regardless of the regimen, it is prudent to have shared decision-making between the treatment team and the patient. The single-dose regimen includes MTX 50 mg/m2 of body surface area intramuscular injection, followed by monitoring of symptoms and measurements of beta-hCG levels at four and seven days after injection. Levels should decrease by at least 15% from day 4 to day 7. If the beta-hCG level does not decrease appropriately or increases, then treatment failure is assumed and additional MTX administration or surgical intervention is indicated.6 (See Table 7.) Levels should be monitored weekly until undetectable, which may take five to seven weeks.6

Table 7. Methotrexate Protocols46 |

|

|

Single Dose |

Administer MTX 50 mg/m2 IM and obtain serum hCG on day 1. Obtain serum hCG on days 4 and 7.

|

|

Two Dose |

Administer MTX 50 mg/m2 IM and obtain serum beta-hCG on

|

|

Multi-Dose |

Administer MTX 1 mg/kg IM and obtain serum beta-hCG on day 1. Administer folinic acid 0.1 mg/kg IM on day 2. Administer second dose of MTX 1 mg/kg IM on day 3. Obtain serum beta-hCG and if > 15% decrease, stop MTX and follow beta-hCG levels weekly. If < 15% decrease, proceed with plan.

|

|

MTX = methotrexate; IM = intramuscular |

|

The overall success of systemic MTX treatment for ectopic pregnancy ranges from 70-95%.7 Beta-hCG levels are the most predictive of successful treatment, with failure rates approaching 40% when the initial beta-hCG level is greater than 2,000 mIU/mL.6 Medical management is more cost-effective and avoids the risks associated with surgery and anesthesia.6 The main drawback is the need for repeated visits over a seven-day period to assess for treatment effectiveness, which may result in loss to follow-up.37

Educate patients who are treated with MTX about the risk of ectopic pregnancy rupture as well as the signs and symptoms of rupture.7 Some patients may experience an increase in abdominal pain six to seven days after receiving the medication, referred to as a separation pain resulting from tubal abortion or hematoma formation with distention of the fallopian tube.9 Patients who were treated with MTX and want to attempt a new conception should delay pregnancy until the medication is cleared from their system, typically at least three months.

Expectant Management

Expectant management is an option for properly selected and counseled patients. Patients who are potential candidates have low and decreasing beta-hCG levels, no evidence of an ectopic mass on TVUS, minimal symptoms, and hemodynamic stability, and are compliant with access to care.2,6,44 Expectant management should be made by the OB/GYN consultant in conjunction with the emergency physician and the patient.

Management includes obtaining a beta-hCG level every 48 hours to confirm there is an appropriate decline, then weekly levels until it is zero. If beta-hCG levels increase or plateau, or if there is increasing pelvic pain or increasing adnexal mass on TVUS, then medical or surgical management is considered.44 Twenty-five percent of ectopic pregnancies are associated with declining beta-hCG levels, and almost 70% of these pregnancies will resolve spontaneously without medical or surgical treatment.44 A drop in a beta-hCG level of at least 15-30% over a 48-hour period suggests that the pregnancy is nonviable, regardless of location, which can justify withholding treatment such as MTX or surgery if the patient is otherwise stable.2

Expectant management success rates are inversely related to beta-hCG levels at diagnosis, with an 80% success rate when the initial beta-hCG level is

< 1,000 mIU/mL.44 Tubal rupture has been documented in asymptomatic patients with low and declining beta-hCG values, so these patients must be counseled on the risk of tubal rupture and the need for close surveillance.44 If the patient develops increasing pain or if beta-hCG levels increase, surgical management is indicated.44 Ensure that patients have access to appropriate medical care and that they understand clearly when to seek care.

Heterotopic Pregnancies

A heterotopic pregnancy is when ectopic and intrauterine gestations occur concurrently. The incidence is quite rare; however, this diagnosis is more frequent in patients who receive ART treatment, where the incidence can be as high as 1 in 100.6,7,9,21,42 Because of the presence of a concurrent intrauterine gestation, there may be a delay in the diagnosis of the ectopic gestation.5

If the ectopic component is ruptured, it typically is treated surgically, and the IUP is expected to continue normally. If the ectopic pregnancy is identified early and is not ruptured, treatment options include expectant management or aspiration and instillation of either potassium chloride or prostaglandin into the gestational sac.4 Systemic MTX or local MTX injection typically is not used if the IUP is desired.4

Rh Status

Rh (D) immune globulin (Rhogam) is indicated within 72 hours for all Rh-negative patients with bleeding, regardless of the final outcome of the pregnancy, to protect against Rh alloimmunization.6 A 50 mcg or 120 mcg dose is recommended before 12 weeks’ gestation, although 300 mcg can be administered if lower doses are not available.

Pregnancy of Unknown Location

It is common for beta-hCG levels to be less than 1,500 mIU/mL with sonographic findings that are not diagnostic for pregnancy location. In these cases, it is reasonable to perform a repeat ultrasound after one week in a stable and asymptomatic patient.29 Early treatment reduces the morbidity associated with a ruptured ectopic pregnancy, but it risks overtreatment of an evolving spontaneous abortion or interruption of a viable pregnancy.6 Alternatively, observation over time allows the provider to determine the location of the pregnancy, but confers the risk of morbidity from a delay in the diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy. These risks and benefits are part of shared decision-making with the patient.

It is appropriate to monitor serial beta-hCG measurements until either a diagnosis is made or until the level is undetectable.13,29 Follow-up to confirm an ectopic pregnancy diagnosis in a stable patient avoids unnecessary exposure to MTX, which can lead to interruption or teratogenicity of an ongoing IUP.7

The PUL can be diagnostically challenging because it does not exclude ectopic pregnancy, and rupture of ectopic pregnancy can occur at any beta-hCG level. Ensure the availability of close follow-up for those patients who are stable and being discharged.

Summary

Ectopic pregnancy has significant health consequences and represents an important cause of morbidity and mortality for women of reproductive age. Making the diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy expeditiously is critical to reduce morbidity and mortality associated with the condition.

A single beta-hCG level cannot diagnose viability or location of a gestation. TVUS is the method of choice for visualizing a pregnancy. The presence of a yolk sac is the first non-controversial finding of an IUP. It generally appears five to six weeks after a woman’s last menstrual period. After a definitive diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy has been made, treatment options include MTX therapy, surgery, or expectant management. Surgical management is indicated for patients who are hemodynamically unstable, have contraindications to medical treatment, or have failed medical treatment.

Heterotopic pregnancies, defined as the presence of multiple gestations with one present in the uterine cavity and the other outside the uterus, are rare historically. However, as infertility treatments are used more widely, the incidence of heterotopic pregnancy has increased.

REFERENCES

- Creanga AA, Shapiro-Mendoza CK, Bish CL, et al. Trends in ectopic pregnancy mortality in the United States. Obstet Gynecol 2011;117:837-843.

- Carusi D. Pregnancy of unknown location: Evaluation and management. Semin Perinatol 2019;43:95-100.

- McGurk L, Oliver R, Odejinmi F. Severe morbidity with ectopic pregnancy is associated with late presentation. J Obstet Gyneacol 2019;39:670-674.

- Hassani KI, Bouazzaoui AE, Khatouf M, Mazaz K. Heterotopic pregnancy: A diagnosis we should suspect more often. J Emerg Trauma Shock 2010;3:304.

- Clayton HB, Schieve LA, Peterson HB, et al. A comparison of heterotopic and intrauterine-only pregnancy outcomes after assisted reproductive technologies in the United States from 1999 to 2002. Fertil Steril 2007;87:303-309.

- Barash JH, Buchanan EM, Hillson C. Diagnosis and management of ectopic pregnancy. Am Fam Physician 2014;90:34-40.

- [No authors listed]. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 193 Summary: Tubal Ectopic Pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 2018;131:613-615.

- Chang J, Elam-Evans LD, Berg CJ, et al. Pregnancy-related mortality surveillance — United States, 1991-1999. MMWR Surveill Summ 2003;52:1-8.

- Seeber BE, Barnhart KT. Suspected ectopic pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 2006;107:399-413.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Ectopic pregnancy — United States, 1990-1992. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 1995;44:46-48.

- Mikhail E, Salemi JL, Schickler R, et al. National rates, trends, and determinants of inpatient surgical management of tubal ectopic pregnancy in the United States, 1998-2011. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 2018;44:730-738.

- Strandell A, Thorburn J, Hamberger L. Risk factors for ectopic pregnancy in assisted reproduction. Fertil Steril 1999;71:282-286.

- Hendriks E, MacNaughton H, MacKenzie MC. First trimester bleeding: Evaluation and management. Am Fam Physician 2019;99:166-174.

- Reekie J, Donovan B, Guy R, et al. Risk of ectopic pregnancy and tubal infertility following gonorrhoea and chlamydia infections. Clin Infect Dis 2019; Feb. 18. doi:10.1093/cid/ciz145. [Epub ahead of print].

- Schrager S, Potter BE. Diethylstilbestrol exposure. Am Fam Physician 2004;69:2395-2400.

- Li C, Zhao WH, Meng CX, et al. Contraceptive use and the risk of ectopic pregnancy: A multi-center case-control study. PLoS One 2014;9:e115031.

- Neth MR, Thompson MA, Gibson CB, et al. Ruptured ectopic pregnancy in the presence of an intrauterine device. Clin Pract Cases Emerg Med 2019;3:51-54.

- Roussos D, Pandis D, Matalliotakis I, et al. Factors that may predispose to rupture of tubal ectopic pregnancy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2000;89:15-17.

- Bouyer J, Coste J, Shojaei T, et al. Risk factors for ectopic pregnancy: A comprehensive analysis based on a large case-control, population-based study in France. Am J Epidemiol 2003;157:185-194.

- Ahmad SF, Brown JK, Campbell LL, et al. Pelvic chlamydial infection predisposes to ectopic pregnancy by upregulating integrin β1 to promote embryo-tubal attachment. EBioMedicine 2018;29:159-165.

- Kirk E. Ultrasound in the diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy. Clin Obstet Gynecol 2012;55:395-401.

- Barnhart KT. Clinical practice. Ectopic pregnancy. N Engl J Med 2009;361:379-387.

- Vagg D, Arsala L, Kathurusinghe S, Ang WC. Intramural ectopic pregnancy following myomectomy. J Investig Med High Impact Case Rep 2018;6:1-4.

- Pedraszewski P, Wlazlak E, Panek W, Surkont G. Cesarean scar pregnancy — a new challenge for obstetricians. J Ultrason 2018;18:56-62.

- Alsuleiman SA, Grimes EM. Ectopic pregnancy: A review of 147 cases. J Reprod Med 1982;27:101-106.

- Dart RG, Kaplan B, Varaklis K. Predictive value of history and physical examination in patients with suspected ectopic pregnancy. Ann Emerg Med 1999;33:283-290.

- Hick JL, Rodgerson JD, Heegaard WG, Sterner S. Vital signs fail to correlate with hemoperitoneum from ruptured ectopic pregnancy. Am J Emerg Med 2001;19:488-491.

- Zachariah SK, Fenn M, Jacob K, et al. Management of acute abdomen in pregnancy: Current perspectives. Int J Womens Health 2019;11:119-134.

- Deutchman M, Tubay AT, Turok D. First trimester bleeding. Am Fam Physician 2009;79:985-994.

- Linden JA, Grimmnitz B, Hagopian L, et al. Is the pelvic examination still crucial in patients presenting to the emergency department with vaginal bleeding or abdominal pain when an intrauterine pregnancy is identified on ultrasonography? A randomized controlled trial. Ann Emerg Med 2017;70:825-834.

- Wilcox AJ, Baird DD, Weinberg CR. Time of implantation of the conceptus and loss of pregnancy. N Engl J Med 1999;340:1796-1799.

- Cole LA, Ladner DG, Byrn FW. The normal variabilities of the menstrual cycle. Fertil Steril 2007;91:522-527.

- Paspulati RM, Bhatt S, Nour SG. Sonographic evaluation of first-trimester bleeding. Radiol Clin North Am 2008;46:437.

- Savaris RF, Braun D, Gibson M. When a pregnancy seems like an ectopic … but isn’t. Obstet Gynecol 2007;109:1439-1442.

- Murray H, Baakdah H, Bardell T, Tulandi T. Diagnosis and treatment of ectopic pregnancy. CMAJ 2005;173:905-912.

- Sivalingam VN, Duncan WC, Kirk E, et al. Diagnosis and management of ectopic pregnancy. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care 2011;37:231-240.

- Brunello J, Guerby P, Cartoux C, et al. Can early βhCG change and baseline progesterone level predict treatment outcome in patients receiving single dose methotrexate protocol for tubal ectopic pregnancy? Arch Gynecol Obstet 2019;299:741-745.

- Dooley WM, Chaggar P, De Braud LV, et al. The effect of morphological types of extrauterine ectopic pregnancies on the accuracy of pre-operative ultrasound diagnosis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2019; Apr 1. doi:10-1002/uog.20274.

- Stein JC, Wang R, Adler N, et al. Emergency physician ultrasonography for evaluating patients at risk for ectopic pregnancy: A meta-analysis. Ann Emerg Med 2010;56:674-683.

- Timor-Tritsch IE. Sliding organs sign in gynecological ultrasound. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2015;46:125-126.

- Jurkovic D, Mavrelos D. Catch me if you scan: Ultrasound diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2007;30:1-7.

- Stanley R, Fiallo F, Nair A. Spontaneous ovarian heterotopic pregnancy. BMJ Case Rep 2018; Aug 9. doi:10.1136/bcr-2018-225619.

- Hajenius PJ, Mol F, Mol BW, et al. Interventions for tubal ectopic pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007;1:CD000324.

- Craig LB, Khan S. Expectant management of ectopic pregnancy. Clin Obstet Gynecol 2012;55:461-470.

- Rodgers SK, Chang C, DeBardeleben JT, Horrow MM. Normal and abnormal US findings in early first-trimester pregnancy: Review of the Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound 2012 Consensus Panel Recommendations. Radiographics 2015;35:2135-2148.

- Alur-Gupta S, Cooney LG, Senapati S, et al. Two-dose versus single-dose methotrexate for treatment of ectopic pregnancy: A meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2019.01.002. [Epub ahead of print].

Ectopic pregnancy has significant health consequences and represents an important cause of morbidity and mortality for women of reproductive age. Making the diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy expeditiously is critical to reduce morbidity and mortality associated with the condition.

Subscribe Now for Access

You have reached your article limit for the month. We hope you found our articles both enjoyable and insightful. For information on new subscriptions, product trials, alternative billing arrangements or group and site discounts please call 800-688-2421. We look forward to having you as a long-term member of the Relias Media community.