Abdominal Pain in Nonpregnant Female Patients

Introduction

Acute pelvic pain in the female patient is a common complaint in the emergency department (ED). For the purposes of classification and discussion, acute pelvic pain is generally defined as pain in the pelvis or lower abdomen lasting less than three months.1 Clinical assessment has limitations, as signs and symptoms, even for classic disorders, are often varied or nonspecific. While some causes of pelvic pain have a low risk for complications, others, such as ovarian torsion, can have significant consequences if not diagnosed and treated promptly. A useful and sometimes critical test is a point-of-care urine pregnancy test obtained as soon as possible, for example at triage. However, pregnancy-related causes of lower abdominal pain are beyond the scope of this article and will not be discussed here. Rather, this article will focus on nonpregnant females of reproductive age who present to the ED with acute pelvic pain. The history, clinical presentation, diagnostic evaluation, and management of female patients with acute pelvic pain will be reviewed, with special emphasis on the safest and most efficient imaging strategies for this patient population.

Executive Summary

- The history and physical exam are the cornerstones of diagnosis, but some serious pelvic conditions can have a nondescript history and minimal physical findings.

- Pelvic ultrasound is the recommended initial imaging modality.

- Because of the incidence of gonococcal and chlamydial infection, have a low threshold for empirically treating women with acute pelvic pain and suggestive physical findings for pelvic inflammatory disease.

- Pain control can facilitate the physical exam, enhancing the ability to localize abnormalities.

History and Physical Examination

An appropriate history and physical exam will narrow the differential diagnosis and help guide the selection of laboratory and radiographic testing. Ask about the onset, location, radiation, mitigating or exacerbating factors, quality, severity, and timing of symptoms. Explore the past medical history, with special emphasis on history of ovarian cysts, uterine fibroids, sexually transmitted infections (STIs), number of sexual partners and use of condoms, and any past gynecological and abdominal surgeries. A study of ED patients diagnosed with ovarian torsion showed that 53% had a known history of ovarian cyst, highlighting the importance of eliciting past gynecologic pathology.2

Patients may not have an accurate recollection of their prior medical conditions, laboratory and imaging results, and surgeries. The explosion of electronic medical records and the growth in health information exchanges enables the physician to often corroborate the past medical history obtained with the patient with searchable records. Spending time to review these documents can be helpful. Conversely, over-influence of past problems on the physician’s analysis can lead to premature closure in the decision making. As the saying goes, the best way to miss something (as in a new condition causing the patient’s current symptoms) is to find something (as in information about a past different diagnosis with similar symptoms).

For the physical examination, note the vital signs and focus on the abdominal examination. Examine the flank and back, as well, to evaluate for costo-vertebral angle (CVA) tenderness or point muscle tenderness, which can signal a urinary or musculoskeletal etiology of pain, respectively. Maneuvers that significantly exacerbate the pain, such as twisting, bending, or flexing the torso, or increased tenderness with tensing the abdominal wall during palpation (Carnett’s test), suggest musculoskeletal causes for the pain.

The next step is to perform a pelvic exam, particularly if gynecological complaints are elicited on history, and especially in patients with undifferentiated lower abdominal pain in which results of history and urinalysis make gastrointestinal and urinary tract diseases less likely. While historically considered one of the most important parts of the physical exam in a female patient with lower abdominal pain, the limitations of this exam and the practical aspects of performing it deserve consideration.

The pelvic exam can be cumbersome in a busy ED, where private rooms and lithotomy stretchers are often in short supply. The exam, which can be uncomfortable and embarrassing for the patient, requires the presence of a chaperone. One study showed that despite attempts to reduce physical and psychological distress of the exam, 41% of women described an ED pelvic exam as being either moderately or severely painful.3

While the use of lithotomy beds is encouraged for better visualization and palpation of pelvic anatomy, placing the patient’s legs in stirrups may actually increase the sense of vulnerability and physical discomfort during a pelvic exam.4 While not ideal, if a lithotomy bed is not available, the pelvic exam can be performed on a regular gurney with the hips flexed and pelvis elevated on a bedpan or stack of blankets. Regardless of the bed, take time to explain each step of the exam to the patient to help reduce any associated anxiety and discomfort.

The authors encourage performing a pelvic exam on all females with acute lower abdominal pain unless another diagnosis is clearly evident and can account for the patient’s symptoms. Furthermore, perform a pelvic exam on all patients with vaginal bleeding, as potential sources can sometimes be identified (e.g., cervical tumors or polyps). It is useful to document the severity of hemorrhage.

Our recommendation for the performance of pelvic exams is tempered by awareness of the exam’s limitations and the accuracy of findings determined by the physician. Emergency physicians (EPs) and residents have poor inter-examiner reliability when it comes to evaluating the uterus, cervix, and adnexa,5 and even gynecology attending physicians are often poor at detecting adnexal masses on exam.6 Since the pelvic exam can lack sensitivity irrespective of examiner level of experience, further testing is often warranted.

Laboratory Evaluation

Once pregnancy has been excluded, ancillary testing is often done on urine and blood samples. With few exceptions, the results of blood count and chemistry panels are rarely diagnostic. Most of the time, the results are normal and serve to provide reassurance of the patient’s general stability and decrease the concern over a rare and unsuspected problem. As discussed below, there are times when blood tests complement the clinical assessment and provide support for a diagnosis.

The urinalysis is a simple test that is most often used to substantiate the clinical diagnosis of a urinary tract infection (UTI). Hematuria is a finding that has a large number of potential causes, some of which originate from the pelvis. If the patient has vaginal bleeding, the clean-catch urine sample is often contaminated by red cells, so if the distinction is important, obtain a catheterized urine sample to determine whether there is true hematuria.

Pyuria (defined as greater than 5 white blood cells [WBC]/high powered field [hpf] on microscopic exam) suggests a possible infection, as bacteria invoke an inflammatory response of the lining of the urinary tract that is shed into the urine. The sensitivity and specificity of pyuria for detecting a UTI varies according to the patient population, age, gender, and symptoms. In general, the sensitivity varies between 80-95%, with only a modest specificity of 50-75%.

The leucocyte esterase (LE) and nitrite (NIT) portions of the urinary dipstick have similar test characteristics as urine microscopy; sensitivities and specificities vary according to the setting. The LE dipstick test has a sensitivity of 84%, with a specificity of 78%.7 The NIT dipstick test has a lower sensitivity at 50%, but has excellent specificity of 98%.7

The urinalysis results should be evaluated in the appropriate clinical context, as pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) and appendicitis can also present with a mild degree of pyuria.8 Similarly, urinary tract symptoms can occur in acute appendicitis and PID, so their presence should not exclude these diagnoses. A greater degree of pyuria typically points toward a UTI rather than to PID or appendicitis. Moderate pyuria (urine WBCs > 50/hpf) and moderate bacteriuria are good predictors of UTI.9

About 8% of patients with acute renal colic have a concomitant UTI; however, pyuria has only a moderate accuracy in identifying an infection in this setting. Clinical features of UTI, a greater degree of pyuria, and female sex increases the likelihood of UTI in the setting of acute renal colic.10

Not all patients with a urinary tract infection benefit from sending a urine culture; the majority of otherwise healthy women respond to empiric antibiotic therapy chosen to be effective against the common urinary pathogens, and the results of the urine culture do not change management or affect outcome. In some forms of urinary infection, urine cultures are recommended because they have a higher likelihood of influencing management after therapy is initiated in the ED. Typical populations in whom urine culture is recommended include women with suspected pyelonephritis, women with recurring or non-resolving symptoms, and women who present with atypical symptoms.11

Blood tests are indicated if the patient has significant pelvic pain and no actionable diagnosis is identified by clinical assessment and the urinalysis. A complete blood cell (CBC) count with differential may find an elevated white blood cell (WBC) count in patients with suspected infection. The hemoglobin and hematocrit measurement is useful in patients with vaginal bleeding or signs of anemia. In patients with intra-abdominal infection, inflammatory serum markers such as C-reactive protein (CRP) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) are often elevated, but the percentage varies according to the duration of symptoms and the cutoff value chosen for a positive test. Thus, normal inflammatory markers should not exclude the diagnosis of infectious processes such as appendicitis, PID, and pyelonephritis. Consider a basic metabolic panel in patients with suspected serious urinary tract pathology and possible renal dysfunction or to evaluate serum electrolytes in patients with vomiting and/or diarrhea.

If a pelvic exam is performed, collect a sample from the cervical canal with a swab that is sent to the laboratory for chlamydia and gonorrhea testing that can be done by a variety of technologies, including culture, nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs), nucleic acid hybridization and transformation tests, enzyme immunoassays (EIAs), and direct fluorescent antibody (DFA) tests. The NAAT technique is recommended by the CDC because of its sensitivity. If a pelvic exam is not performed, urine can be analyzed by NAATs with sensitivities and specificities nearly identical to that from endocervical samples.12 If a sexually transmitted infection (STI) is suspected, include testing for syphilis with either a VDRL or RPR.

In patients who might require a blood transfusion or emergency surgery, consider ordering a type and screen from the blood bank. Coagulation factor disorders are not common causes of uterine bleeding, so routine coagulation studies are not indicated, but should be considered in patients with very heavy vaginal bleeding or a hemoperitoneum.

Differential Diagnosis

When considering the differential diagnoses to guide further assessment, it is beneficial to think of the lower abdomen as divided into thirds, with each third associated with possible diagnoses for acute pelvic pain. (See Table 1.)

Table 1: Differential Diagnosis of Acute Pelvic Pain

| Location of Pain | Differential |

|---|---|

|

Right lower abdomen |

Gynecologic: Ovarian torsion, TOA/PID, hemorrhagic ovarian cyst, mittelschmerz Genitourinary: Pyelonephritis, renal colic Gastrointestinal: Appendicitis, colitis |

|

Mid or entire lower abdomen |

Gynecologic: Degenerating fibroid, endometriosis, PID, adenomyosis, dysmenorrhea Genitourinary: Cystitis, urinary retention Gastrointestinal: Colitis, IBD, IBS |

|

Left lower abdomen |

Gynecologic: Ovarian torsion, TOA/PID, hemorrhagic ovarian cyst, mittleshmerz Genitourinary: Pyelonephritis, renal colic Gastrointestinal: Diverticulitis, colitis |

Differential Diagnoses: Nongynecologic

In the nonpregnant patient, gastrointestinal and genitourinary pathologies can present with acute lower abdominal or pelvic pain. When the patient has classic symptoms and signs, the diagnosis of acute appendicitis, nephrolithiasis, or bowel disease can be made with reasonable confidence, especially if the pelvic exam is unremarkable.

Appendicitis. The presentation for appendicitis is notoriously variable, and individual symptoms and signs are inconsistently present. Periumbilical pain migrating to the right lower quadrant and associated with nausea and anorexia is only seen in 50% of patients presenting with appendicitis. It is possible for none of these "classic" features to be present. About 18% of patients present with atypical symptoms of diarrhea or constipation, resulting in the common misdiagnosis of gastroenteritis.13

Figure 1: Appendicitis

Ultrasound of an inflamed appendix demonstrating a blind-ended, tubular, non-peristalsing, non-compressible structure measuring > 8 mm in diameter with a small amount of peri-appendiceal fluid. Other sonographic features of appendicitis include presence of an appendicolith and appendiceal wall hyperemia.

Furthermore, in a study of 500 patients with acute appendicitis, one-third of patients complained of dysuria or flank pain, and one in seven patients had pyuria greater than 10 WBCs/hpf.14

For patients who require imaging to accurately make the diagnosis of acute appendicitis, the American College of Radiology recommends a CT scan.15 While traditionally a CT with intravenous contrast is performed, multiple articles suggest that noncontrast CT is an accurate and effective technique for diagnosing acute appendicitis and has the added benefit of being less time-consuming and avoiding potential contrast-related reactions.16-18

Gynecologic causes of lower abdominal pain often mimic appendicitis, and the highest percentage of misdiagnosis occurs in women of childbearing age.19 Because clinical diagnosis is less certain in women, it is a common practice to obtain an imaging study in women with suspected appendicitis. As an alternative to CT in a thin, cooperative female with lower abdominal pain, consider ultrasound as the initial imaging modality for evaluation of the appendix, as this approach can reduce exposure to potentially harmful ionizing radiation.

Sonographically, the appendix appears as a blind-ended, tubular structure that lacks peristalsis and traces back to the cecum. An inflamed appendix typically measures greater than 6-8 mm in diameter, is noncompressible, and can be associated with an appendicolith with posterior shadowing, appendiceal wall hyperemia, and/or peri-appendiceal fluid. (See Figure 1.) While sonographic appendix visualization rates range from 22% to 98%, and sensitivities for acute appendicitis range from 83% to 88%, specificities of sonographic diagnosis of appendicitis were comparable to that of CT, at about 94% for both adults and children once the appendix was visualized.20

While appendicitis is a common cause of right lower quadrant pain, ovarian torsion has also been noted to have a slight (3:2) right-sided predisposition (presumably due to the effects of the sigmoid colon being on the left).21 This further supports the use of ultrasound as the primary imaging modality in a young healthy female to simultaneously evaluate for both etiologies. Because of lower sonographic accuracy, if the ultrasound is negative or equivocal for appendicitis or pelvic pathology, proceed to CT.

While a delay in the diagnosis of acute appendicitis is more common in women than men, it generally does not lead to an increased incidence of complications. Overall, the risk of appendiceal rupture increases after 24-36 hours,22 so a delay of 12 hours is acceptable without any increased risk of rupture, complications of appendectomy, operative time, or hospital stay. If the initial evaluation is nondiagnostic, there is value in a period of observation or instructions to return for repeat evaluation in 12 hours.23

Renal Colic. The classic presentation for acute renal colic is sudden onset of severe flank pain with radiation to the groin. At least 50% of patients will also have nausea and vomiting. Gross or microscopic hematuria is present in approximately 85% of patients with kidney stones, but the degree of hematuria is not predictive of stone size or likelihood of passage.24

While CT is often the modality of choice for first presentation of renal colic, unclear diagnosis, or for the possibility of associated urinary tract infection, not all patients require imaging in the ED; such studies can safely be deferred until after ED discharge. If the patient is pain-free after receiving analgesics, she can be discharged from the ED to undergo outpatient radiologic imaging in 2-3 weeks without increased morbidity.25

Clinician-performed ultrasound may also be used as an adjunct in the evaluation of a patient with suspected renal colic. In a retrospective review of 177 patients who had a renal ultrasound performed by the EP, as well as a noncontrast CT, patients with no or mild hydronephrosis on sonography were less likely to have a stone of greater than 5 mm on CT. The negative predictive value was 88%, indicating that this degree of hydronephrosis is generally associated with a smaller stone.26 However, because larger stones will sometimes have mild or no hydronephrosis, persistent pain despite analgesics can be used to decide when a CT scan should be performed.

Urinary Tract Infections. Features of acute uncomplicated UTI are frequency and dysuria. In an immunocompetent woman of childbearing age who has no comorbidities or urologic abnormalities, treatment is with oral antibiotics. Young, healthy females with flank pain or CVA tenderness without concern for structural abnormality may also be treated with a course of oral antibiotics for presumed pyelonephritis as long as vital signs are normal. Flank pain is nearly universal in patients with pyelonephritis, and its absence should raise suspicion for an alternate diagnosis.27 A low threshold for admission and treatment with intravenous antibiotics is encouraged if there is evidence of early sepsis, as hematogenous spread of infection is possible.

Figure 2: Pyelonephritis

Renal ultrasound with color Doppler demonstrating decreased perfusion to the affected parenchyma (asterisk).

Most women with acute pyelonephritis do not need imaging unless symptoms do not improve or there is a recurrence.28 Imaging serves to identify an underlying structural abnormality, such as occult obstruction from a stone or an abscess. CT with contrast is considered the imaging modality of choice in nonpregnant women. Alternatively, renal sonography can be used as well, with high sensitivity and specificity for detecting parenchymal changes in acute pyelonephritis.29 Common sonographic findings associated with pyelonephritis include diffuse or focal enlargement of the kidney (normal length is 8-12 cm) and variations in parenchymal echogenicity (usually hyperechoic).30 Color and power Doppler evaluation typically demonstrates decreased perfusion to the affected parenchyma, thought to be due to arteriolar vasoconstriction and interstitial edema in response to bacterial infection.31 (See Figure 2.) A kidney with pyelonephritis frequently appears normal on ultrasound, so this imaging modality should not be used to rule out disease.

Colitis, Inflammatory Bowel Disease, and Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Diarrheal diseases account for 20-35 million episodes of illness yearly in the United States, often with associated abdominal pain. Lower abdominal pain associated with watery or bloody diarrhea should raise suspicion for a gastrointestinal etiology.

Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC) are idiopathic, inflammatory bowel diseases that usually cause chronic, recurring abdominal pain. Most patients are diagnosed in the second or third decade of life, so it is possible for females of reproductive age to present with acute lower abdominal pain in the setting of an initial episode.32

Most cases of inflammatory bowel disease diagnosed in the ED are found after a CT is performed on patients with severe, unexplained abdominal pain.33 Final diagnosis is made via colonoscopy and biopsy. The sensitivity of CT for inflammatory bowel disease varies between 70% and 90%, depending on the extent of disease and severity. Thus, a normal CT does not exclude the diagnosis.

CT is used in patients with known disease who present with acute abdominal pain, especially with peritoneal findings or sepsis, to exclude abscesses or other intra-abdominal disease. Patients who present to the ED with an exacerbation of known inflammatory bowel disease and do not have peritoneal signs or findings of sepsis do not require CT.

Pseudomembranous colitis is another potential cause of acute lower abdominal pain that typically presents with profuse watery or mucoid diarrhea associated with tenesmus, fever, abdominal cramps, and abdominal tenderness. A history of antibiotic therapy within one week may be elicited. Stools may be frankly bloody or Hemoccult®-positive. The stool should be tested for Clostridium difficile toxin. CT can be used to evaluate patients who appear particularly ill and to detect intra-abdominal complications, such as toxic megacolon.

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a functional gastrointestinal disease characterized by abdominal pain and altered bowel habits. Common sites of pain include the lower abdomen, specifically the left lower quadrant. While pain is typically a chronic dull ache, acute episodes of sharp pain can compel patients to seek care in the ED.

The diagnosis of IBS is suspected based on characteristic features in the history as defined in the Rome III criteria: patients with recurrent abdominal pain or discomfort at least 3 days per month during the previous 3 months that is associated with 2 or more of the following: relief with defecation, onset associated with a change in stool frequency, or onset associated with a change in stool form or appearance.34

The physical exam in patients with IBS may demonstrate tenderness, but there should not be signs of inflammation (guarding or rebound), and laboratory results should not show abnormalities. Management consists primarily of providing psychological support, recommending dietary measures, and gastroenterology referral.

Differential Diagnoses: Gynecologic

In the nonpregnant patient, ovarian torsion is the most serious gynecologic cause of acute pelvic pain in which emergent identification is necessary to prevent ovarian infarction and prevent infertility. Ovarian masses, such as hemorrhagic cysts and endometriomas, can cause peritoneal irritation and acute pelvic pain as well, especially after rupture. Dysmenorrhea and mittelschmerz (pain with ovulation) can cause severe, recurrent pelvic pain, with diagnosis facilitated based on their occurrence at specific phases of the menstrual cycle. Note that primary dysmenorrheic pain can be intense and justifies swift treatment by the EP to facilitate patient comfort.35

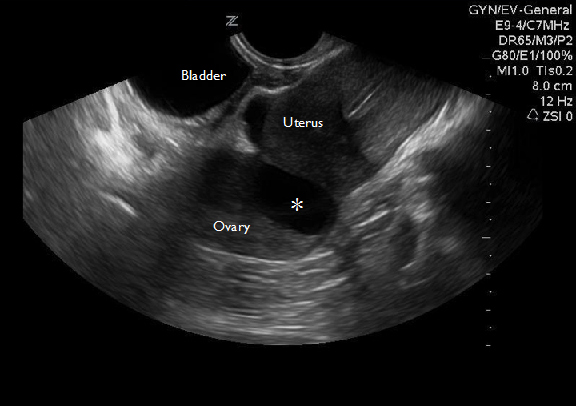

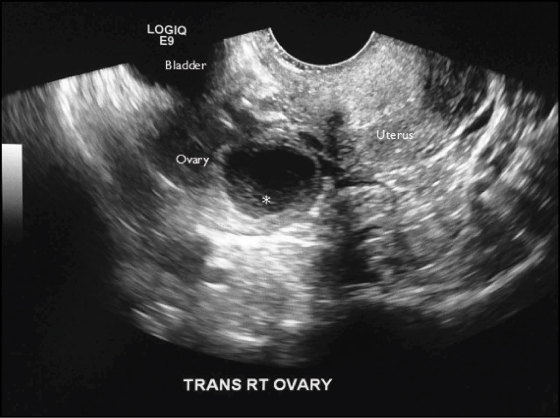

Figure 3A: Ovarian Torsion

Transvaginal ultrasound of an enlarged ovary with an ovarian cyst (asterisk) that acted as a lead point for torsion.

Figure 3B: Ovarian Torsion

Transvaginal ultrasound of an enlarged ovary demonstrating multiple peripheral follicles due to vascular congestion.

Patients with exacerbations of chronic pelvic pain, defined as nonmenstrual pain of 3 months duration or longer that localizes to the anatomic pelvis, often seek care in the ED. Chronic pelvic pain can cause significant functional disability and usually requires outpatient specialty referral. A detailed history and review of available medical records is important if chronic pelvic pain is suspected, as this will prevent the patient from receiving repeat invasive and potentially harmful procedures.36

Tubo-ovarian abscess (TOA) and PID can cause pelvic pain, and if on the right, may mimic appendicitis, as they are often associated with fever and leukocytosis.37 Uterine fibroids, while largely asymptomatic, can also cause acute pelvic pain or bleeding if they undergo torsion, necrosis, or prolapse through the cervix.

Ovarian Torsion. Always consider ovarian torsion in the female patient with acute unilateral pelvic pain. The prevalence of ovarian torsion is greatest in women in their reproductive years, likely due to the increased occurrence of physiologic and pathologic ovarian masses, as well as therapy for infertility.38

Although torsion can occur in normal ovaries, increased incidence is associated with a long mesosalpinx and ovarian masses that can act as a lead point for torsion. The masses are typically benign, such as ovarian cysts or teratomas. Malignant ovarian masses or ovarian enlargement due to hyperstimulation syndrome or polycystic ovary also increase the risk for torsion.

Although less common, ovarian torsion may only present with subtle findings such as ovarian enlargement or an adnexal mass. A retrospective review of 87 cases of surgically confirmed ovarian torsion noted that 29% of patients had no tenderness and 53% had no palpable mass on initial physical examination.2

Ultrasound is considered the gold standard for diagnosis of ovarian torsion, and should be the initial imaging choice for acute pelvic pain.39

The most consistent sonographic finding in ovarian torsion is a unilaterally enlarged ovary.40 The ovary can also demonstrate multiple peripheral follicles measuring 8-12 mm, thought to be due to transudation of fluid into follicles from vascular congestion. (See Figures 3A and 3B.) Fluid in the cul-de-sac may be present. The ovary may be displaced medially, or it may be posterior or superior to the uterus due to twisting of the pedicle.38

The absence of venous waveforms within the ovary has been shown to have a positive predictive value for torsion in 94% of cases.41 However, it is crucial to recognize that the presence of arterial and venous flow does not exclude torsion because the ovaries have dual blood supply. In cases in which clinical suspicion is high despite positive flow on ultrasound, consulting gynecology and advocating laparoscopy for visual inspection to exclude ovarian torsion is an approach supported by some authors.42

Hemorrhagic Ovarian Cyst. Benign ovarian masses such as hemorrhagic cysts can also cause acute pelvic pain without torsion. A functional ovarian cyst is a sac that forms on the surface of the ovary during or after ovulation. It holds a maturing egg and usually resolves after the egg is released. Bleeding into a functional ovarian cyst can cause stretching of the ovarian parenchyma, and rupture of the cyst can cause irritation of the peritoneum, producing acute pelvic pain.

Sonography has a high positive predictive value in the diagnosis of hemorrhagic ovarian cysts. Characteristic sonographic features include an avascular hypoechoic mass with fine linear echoes that have a "fish-net" appearance and represent internal fibrin stranding. It is also typical to see a retracting clot with concave margins along the wall of the cyst.39 (See Figures 4A and 4B.)

Figure 4A: Hemorrhagic Cyst

Transvaginal ultrasound of a hemorrhagic cyst demonstrating a retracting clot (asterisk) with concave margins along the wall of the cyst.

Figure 4B: Hemorrhagic Cyst

Note the fine linear echoes (asterisk) consistent with internal fibrin stranding.

Rarely, a hemorrhagic cyst that results in a large amount of pelvic bleeding may require a blood transfusion or operative intervention for hemostasis. Most hemorrhagic cysts resolve within 8 weeks, with 30% resolving in 2 weeks; thus, short-term follow-up with a gynecologist in 4-12 weeks is recommended.43

Endometriosis and Endometriomas. Endometriosis is characterized by the presence of endometrial tissue located outside of the uterus. This ectopic endometrium can be a cause of acute pelvic pain, dysmenorrhea, and adhesions. Implantation sites include the ovary (most commonly), uterine ligaments, cul-de-sac, fallopian tubes, and sigmoid colon. While small implants and adhesions cause pain, they are not well visualized by sonographic or CT imaging, and usually require laparoscopy for definitive diagnosis.

Larger adnexal implants are termed endometriomas, which may lead to endometriotic cysts, also known as "chocolate cysts," essentially a collection of blood around an area of endometriosis. Endometriomas can rupture, causing pelvic pain due to hemoperitoneum. While laparoscopy is the gold standard for the diagnosis of endometriosis, sonography can achieve a high degree of accuracy in diagnosing endometriomas.44 Endometriomas may have a variety of appearances on ultrasound, but the most suggestive sonographic features include the presence of a hypoechoic mass that contains diffuse, homogeneous, low-level internal echoes and hyperechoic wall foci.45-46 (See Figure 5.)

Figure 5: Endometrioma

Transvaginal ultrasound demonstrating two endometriomas (asterisks) with homogeneous low-level internal echoes and hyperechoic wall foci.

Stable patients with endometriomas can be discharged with gynecologic follow up for repeat imaging, especially if the endometrioma has atypical features. Due to the risk of malignant transformation, endometriomas are frequently removed.47

Pelvic Inflammatory Disease and Tubo-ovarian Abscess. Pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) is an infection of the female reproductive organs that usually begins in the vagina and ascends through the cervix to the uterus, fallopian tubes, and/or ovaries. Patients classically present with acute lower abdominal pain and purulent vaginal discharge. Cervical motion tenderness and uterine and/or bilateral adnexal tenderness are key clinical signs. However, PID can have physical exam findings that range from mild subclinical disease to frank peritonitis.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommend empiric treatment for PID in sexually active young women (25 years old or younger) and other women at risk of STI (multiple sex partners or history of STI) if they are experiencing acute pelvic or lower abdominal pain, if no cause for the illness other than PID can be identified, and if one or more of the following is appreciated on bimanual pelvic examination: cervical motion tenderness, uterine tenderness, or adnexal tenderness.48

In more severe cases of PID, fever, leukocytosis, elevated ESR and CRP, and an adnexal mass may be present. Under these circumstances, transvaginal sonography is indicated to rule out a tubo-ovarian abscess (TOA).

Sonographically, a TOA appears as a mass-like, heterogeneous structure with peripheral hyperemia and posterior acoustic enhancement.39 (See Figure 6A.) Ultrasound can also reveal a thickened or slightly heterogeneous endometrial stripe if endometritis is present, or a dilated and debris- or fluid-filled fallopian tube consistent with salpingitis. (See Figure 6B.)

Figure 6A: Tubo-ovarian Abscess

Transvaginal color Doppler ultrasound of a TOA demonstrating hyperemia and posterior acoustic enhancement (asterisk).

Figure 6B: Tubo-ovarian Abscess

Transvaginal ultrasound of a fluid-filled fallopian tube consistent with salpingitis.

Approximately 10-15% of cases of PID will be associated with a TOA, which can be an indication for hospitalization and IV antibiotics.49 For most small- to medium-sized TOAs, antibiotic therapy alone can be curative, while larger TOAs may require additional intervention, such as minimally invasive drainage procedures or invasive surgery. Intra-peritoneal rupture of a TOA can result in septic shock.

Uterine Leiomyomas. Uterine leiomyomas (also called fibroids or myomas) are common in females of reproductive age. Fibroids are identified in 4% of women age 20 to 30, 11-33% of women age 30 to 40, and 33% of women age 40 to 60. They are more common in African-American women, nulliparous women, obese women, and women with a positive family history of fibroids.50-52

Symptoms of fibroids include pelvic pain, menorrhagia, infertility, pregnancy loss, pelvic pressure, or obstructive symptoms due to the size and location of fibroids.53 Fibroids may cause acute pelvic pain due to uterine cramping or fibroid degeneration. Degeneration occurs in about 4% of fibroids and is thought to be due to infarction as the tumor outgrows its blood supply.54

Fibroids often cannot be palpated on exam, and ultrasound is the preferred imaging modality for initial evaluation. Sonographically, fibroids typically appear as well-defined, solid masses with a whorled appearance. (See Figure 7.) These masses are usually isoechoic or hypoechoic when compared to the myometrium and can cause an alteration of the normal contour of the uterus. Degenerating fibroids may have a complex appearance with areas of cystic change.55

While CT is not the imaging modality of choice, fibroids are often found incidentally on CT scan. The typical finding on CT is a bulky, irregular uterus or a mass that is continuous with the uterus. Degenerating fibroids can appear complex, with areas of fluid attenuation or peripheral calcification. Once fibroids are diagnosed, outpatient MRI is the preferred imaging modality for characterizing uterine fibroids and identifying their exact anatomical location.

Figure 7: Uterine Fibroids

Transvaginal ultrasound demonstrating two well-defined solid masses with a whorled appearance.

Typically, treatment is reserved for symptomatic fibroids, and includes both medical and surgical therapy. Although rapid growth of fibroids may raise concern for malignancy (leiomyosarcoma), studies report the incidence is quite low (0.27%), even in patients with rapidly enlarging fibroids.56

Adenomyosis. Adenomyosis is characterized by ectopic glandular tissue found in the myometrium of the uterus. In this condition, infiltration of endometrium causes a hypertrophic and hyperplastic reaction within the myometrial smooth muscle.

Adenomyosis is found in 20-30% of the general female population and is most common between the ages of 35 and 50. While many patients are asymptomatic, symptoms, if present, can be debilitating, with severe cramping and sharp, knife-like pelvic pain during menstrual shedding of the endometrium. Associated symptoms include abdominal enlargement, pelvic pressure, abnormal uterine bleeding, dysmenorrhea, and dyspareunia.53

Pelvic examination can reveal bleeding, as most patients present during times of uterine bleeding, cervical motion tenderness, or adnexal tenderness with a large, full uterus. Adenomyosis is often associated with leiomyomata or endometriosis.

While adenomyosis is usually confirmed by MRI or surgical specimen, sonography is the recommended initial imaging modality. A recent meta-analysis of the accuracy of ultrasound in the diagnosis of adenomyosis showed that it has a sensitivity of 82.5% and a specificity of 84.6%.57 The sonographic markers of adenomyosis include any of the following: uterine enlargement, cystic anechoic spaces in the myometrium, uterine wall thickening (most commonly the posterior wall), subendometrial echogenic linear striations, heterogeneous echo texture, and an obscure endometrial/myometrial border.53 (See Figure 8.)

Figure 8: Adenomyosis

Transvaginal ultrasound demonstrating uterine enlargement with heterogeneous echo texture, cystic anechoic spaces in the myometrium, and posterior uterine wall thickening.

For patients presenting with possible adenomyosis, the ED course typically includes provision of pain medications, evaluation for hemodynamic stability if severe menorrhagia is present, and discharge with gynecologic referral for further treatment.

Malignant Masses. While peak incidence of ovarian tumors is in women 55 to 65 years of age, approximately 30% of women are diagnosed with ovarian cancer in their reproductive years.58 Patients may present with acute pelvic pain related to mass effect, typically associated with pelvic pressure and bloating. Patients may also complain of urinary frequency, constipation, or vaginal bleeding due to abnormal hormone secretion.54

If physical examination reveals a mass, this should be evaluated by pelvic ultrasound, either in the hospital if the patient requires admission for heavy bleeding and/or pain management, or coordinated with outpatient gynecology. If the origin of a pelvic mass is in doubt, MRI is indicated.

Imaging Considerations for Nonpregnant Females with Acute Pelvic Pain

The American College of Radiology recommends sonography as the initial imaging modality for the evaluation of acute pelvic pain in women of childbearing age.59 Ultrasound is noninvasive, radiation free, and cost-effective, demonstrating high sensitivities across critical etiologies of pelvic pain such as ovarian torsion, ovarian cyst, and pelvic inflammatory disease. Many studies report the success of using pelvic ultrasound in diagnosing other etiologies of acute pelvic pain as well.37-39, 60-69

Often, likely due to the widespread availability of the machine, CT is the initial imaging modality chosen to evaluate females who present with lower abdominal and pelvic pain.70 As noted, CT is not the best imaging modality for gynecologic conditions. An abdomino-pelvic CT exposes a patient to a radiation dose equivalent to 200 plain radiographs.1

A recent study showed that 40% of emergency abdomino-pelvic CT scans performed on women of reproductive age had negative findings. Furthermore, 22% of CT scans revealed only gynecologic conditions, which could have been identified just as accurately with ultrasound.70

Similarly, a prospective study of 1,011 patients evaluated in the ED for lower abdominal and pelvic pain found that the highest sensitivity and least amount of radiation exposure was achieved using ultrasound as the initial imaging modality, followed by CT in circumstances in which ultrasound results were negative or indeterminate.60 Other studies using diagnostic imaging algorithms with ultrasound as the initial imaging test have revealed similar results.71,72

An occasional statement on the CT interpretation is that when pelvic pathology is being considered, ultrasound may be useful to identify a potential problem not apparent on CT. The value of this recommendation has not be validated, and at least one study showed that if CT is ordered first for acute lower abdominal pain, immediate re-imaging with pelvic ultrasound after negative CT scan typically does not yield additional information or alter acute care.73

Clinician-Performed Ultrasound in the ED. Oftentimes, the rate-limiting factor in performing a pelvic ultrasound for women with acute pelvic pain is the availability of trained sonographers. In some settings, sonographers are not available past business hours or may need to be called in from home, which can delay the study for more than an hour. If an ultrasound is not available, the EP may resort to ordering a CT scan instead, contributing to their overuse.

Many EDs have attempted to remedy this situation and make ultrasound more available by training EPs to perform pelvic ultrasound at the bedside. Termed clinician-performed ultrasound, it can be a safe, accurate, and efficient diagnostic tool across multiple applications.

The advantages of clinician-performed pelvic ultrasound in pregnant females include significantly reduced length of stay in the ED.74,75 Clinician-performed pelvic ultrasound has also been shown to be useful in women with symptoms of PID in the diagnosis of TOAs, in the diagnosis of appendicitis, and for decision making in nonpregnant female patients with undifferentiated right lower quadrant pain.61,76,77

Conclusion

The history and physical exam are the cornerstones of the diagnosis of acute pelvic pain. However, some acute pelvic pain conditions may have minimal physical findings, so imaging is often necessary to exclude potentially serious conditions. Pelvic ultrasound is the recommended initial imaging modality. Clinician-performed ultrasound can lead to more rapid diagnosis and shorten ED length of stay.

References

- Kruszka PS, Kruszka SJ. Evaluation of acute pelvic pain in women. Am Fam Physician 2010;82(2):141147.

- Houry D, Abbott JT. Ovarian torsion: A fifteen-year review. Ann Emerg Med 2001;38(2):156159.

- Patton KR, Bartfield JM, McErlean M. The effect of practitioner characteristics on patient pain and embarrassment during ED internal examinations. Am J Emerg Med 2003;21(3):205207.

- Seehusen DA, Johnson DR, Earwood JS, et al. Improving women’s experience during speculum examinations at routine gynaecological visits: Randomised clinical trial. BMJ 2006;333(7560):171.

- Close RJ, Sachs CJ, Dyne PL. Reliability of bimanual pelvic examinations performed in emergency departments. West J Med 2001;175(4):240244discussion 244245.

- Padilla LA, Radosevich DM, Milad MP. Accuracy of the pelvic examination in detecting adnexal masses. Obstet Gynecol 2000;96(4):593598.

- Mellick L. Positive nitrites and negative leukocytes? Emergency Medicine Pearls and Pitfalls. Available at http://www.reliasmedia.com/emreports/pearls/pearls36.html.

- Tanagho EA, McAninch JW. Smith’s General Urology. 14th ed. East Norwalk, Conn: Appleton and Lange; 1995.

- Meister L, Morley EJ, Scheer D, et al. History and physical examination plus laboratory testing for the diagnosis of adult female urinary tract infection. Acad Emerg Med 2013;20(7):631645.

- Abrahamian FM, Krishnadasan A, Mower WR, et al. Association of pyuria and clinical characteristics with the presence of urinary tract infection among patients with acute nephrolithiasis. Ann Emerg Med 2013;62(5):526533.

- Colgan R, Williams M. Diagnosis and treatment of acute uncomplicated cystitis. Am Fam Physician 2011;84(7):771776.

- Cook RL, Hutchison SL, Østergaard L, et al. Systematic review: Noninvasive testing for Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Ann Intern Med 2005;142(11):914925.

- Yeh B. Evidence-based emergency medicine/rational clinical examination abstract. Does this adult patient have appendicitis? Ann Emerg Med 2008;52(3):301-303

- Tundidor Bermúdez AM, Amado Diéguez JA, Montes de Oca Mastrapa JL. [Urological manifestations of acute appendicitis]. Arch Esp Urol 2005;58(3):207212.

- American College of Radiology. ACR Appropriateness Criteria: Right lower quadrant pain — suspected appendicitis. American College of Radiology website. http://acr.org/~/media/ACR/Documents/ AppCriteria/Diagnostic/

R\ightLowerQuadrantPainSuspectedAppen- dicitis.pdf. Accessed Dec. 12, 2013. - Ege G, Akman H, Sahin A, et al. Diagnostic value of unenhanced helical CT in adult patients with suspected acute appendicitis. Br J Radiol 2002;75(897):721725.

- MacKersie AB, Lane MJ, Gerhardt RT, et al. Nontraumatic acute abdominal pain: Unenhanced helical CT compared with three-view acute abdominal series. Radiology 2005;237(1):114122.

- Lane MJ, Katz DS, Ross BA, et al. Unenhanced helical CT for suspected acute appendicitis. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1997;168(2):405409.

- Paulson EK, Kalady MF, Pappas TN. Clinical practice. Suspected appendicitis. N Engl J Med 2003;348(3):236242.

- Doria AS, Moineddin R, Kellenberger CJ, et al. US or CT for diagnosis of appendicitis in children and adults? A meta-analysis. Radiology 2006;241(1):8394.

- Chiou S-Y, Lev-Toaff AS, Masuda E, et al. Adnexal torsion: New clinical and imaging observations by sonography, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging. J Ultrasound Med 2007;26(10):12891301.

- Bickell NA, Aufses AH, Rojas M, et al. How time affects the risk of rupture in appendicitis. J Am Coll Surg 2006;202(3):401406.

- Abou-Nukta F, Bakhos C, Arroyo K, et al. Effects of delaying appendectomy for acute appendicitis for 12 to 24 hours. Arch Surg 2006;141(5):504506discussion 506507.

- Press SM, Smith AD. Incidence of negative hematuria in patients with acute urinary lithiasis presenting to the emergency room with flank pain. Urology 1995;45(5):753757.

- Lindqvist K, Hellström M, Holmberg G, et al. Immediate versus deferred radiological investigation after acute renal colic: A prospective randomized study. Scand J Urol Nephrol 2006;40(2):119124.

- Goertz JK, Lotterman S. Can the degree of hydronephrosis on ultrasound predict kidney stone size? Am J Emerg Med 2010;28(7):813816.

- Colgan R, Williams M, Johnson JR. Diagnosis and treatment of acute pyelonephritis in women. Am Fam Physician 2011;84(5):519526.

- American College of Radiology. ACR Appropriateness Criteria. Acute pyelonephritis.http://www.acr.org/secondarymainmenucategories/quality_safety/app_criteria/pdf/expertpanelonurologicimaging/acutepyelonephritisdoc3.aspx. Accessed December 20, 2013.

- Mitterberger M, Pinggera GM, Colleselli D, et al. Acute pyelonephritis: Comparison of diagnosis with computed tomography and contrast-enhanced ultrasonography. BJU Int 2008;101(3):341344.

- Farmer KD, Gellett LR, Dubbins PA. The sonographic appearance of acute focal pyelonephritis 8 years experience. Clinical Radiology 2002;57(6):483487.

- Majd M, Nussbaum Blask AR, Markle BM, et al. Acute pyelonephritis: Comparison of diagnosis with 99mTc-DMSA, SPECT, spiral CT, MR imaging, and power Doppler US in an experimental pig model. Radiology 2001;218(1):101108.

- Howard FH. Pelvic Pain: Diagnosis and Management. Philadelphia, PA. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: 2000.

- Adams JG. Emergency Medicine. Philadelphia, PA. Saunders Elsevier: 2008.

- Longstreth GF, Thompson WG, Chey WD, et al. Functional bowel disorders. Gastroenterology 2006;130(5):14801491.

- Ayan M, Sogut E, Tas U, et al. Pain levels associated with renal colic and primary dysmenorrhea: A prospective controlled study with objective and subjective outcomes. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2012;286(2):403409.

- Neis KJ, Neis F. Chronic pelvic pain: Cause, diagnosis and therapy from a gynaecologist’s and an endoscopist’s point of view. Gynecol Endocrinol 2009;25(11):757-761.

- Shadinger LL, Andreotti RF, Kurian RL. Preoperative sonographic and clinical characteristics as predictors of ovarian torsion. J Ultrasound Med 2008;27(1):713.

- Chang HC, Bhatt S, Dogra VS. Pearls and pitfalls in diagnosis of ovarian torsion. Radiographics 2008;28(5):13551368.

- Kamaya A, Shin L, Chen B, et al. Emergency gynecologic imaging. Semin Ultrasound CT MR 2008;29(5):353368.

- Albayram F, Hamper UM. Ovarian and adnexal torsion: Spectrum of sonographic findings with pathologic correlation. J Ultrasound Med 2001;20(10):10831089.

- Ben-Ami M, Perlitz Y, Haddad S. The effectiveness of spectral and color Doppler in predicting ovarian torsion. A prospective study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2002;104(1):6466.

- White M, Stella J. Ovarian torsion: 10-year perspective. Emerg Med Australas 2005;17(3):231237.

- Okai T, Kobayashi K, Ryo E, et al. Transvaginal sonographic appearance of hemorrhagic functional ovarian cysts and their spontaneous regression. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 1994;44(1):4752.

- Moore J, Copley S, Morris J, et al. A systematic review of the accuracy of ultrasound in the diagnosis of endometriosis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2002;20(6):630634.

- Asch E, Levine D. Variations in appearance of endometriomas. J Ultrasound Med 2007;26(8):9931002.

- Patel MD, Feldstein VA, Chen DC, et al. Endometriomas: Diagnostic performance of US. Radiology 1999;210(3):739745.

- Heaps JM, Nieberg RK, Berek JS. Malignant neoplasms arising in endometriosis. Obstet Gynecol 1990;75:10231028.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines. Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep 2010;59 RR-12.

- Paik CK, Waetjen LE, Xing G, et al. Hospitalizations for pelvic inflammatory disease and tuboovarian abscess. Obstet Gynecol 2006;107(3):611616.

- Lurie S, Piper I, Woliovitch I, et al. Age-related prevalence of sonographically confirmed uterine myomas. J Obstet Gynaecol 2005;25(1):4244.

- Kjerulff KH, Langenberg P, Seidman JD, et al. Uterine leiomyomas. Racial differences in severity, symptoms and age at diagnosis. J Reprod Med 1996;41(7):

483490. - Wise LA, Palmer JR, Stewart EA, et al. Age-specific incidence rates for self-reported uterine leiomyomata in the Black Women’s Health Study. Obstet Gynecol 2005;105(3):563568.

- Shwayder J, Sakhel K. Imaging for uterine myomas and adenomyosis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 2013; Dec 3 [Epub ahead of print].

- Ueda H, Togashi K, Konishi I, et al. Unusual appearances of uterine leiomyomas: MR imaging findings and their histopathologic backgrounds. Radiographics 1999;19 Spec No:S131145.

- Wilde S, Scott-Barrett S. Radiological appearances of uterine fibroids. Indian J Radiol Imaging 2009;19(3):222231.

- Parker WH, Fu YS, Berek JS. Uterine sarcoma in patients operated on for presumed leiomyoma and rapidly growing leiomyoma. Obstet Gynecol 1994;83(3):414418.

- Meredith SM, Sanchez-Ramos L, Kaunitz AM. Diagnostic accuracy of transvaginal sonography for the diagnosis of adenomyosis: Systematic review and metaanalysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2009;201(1):107.e16.

- Ovarian Cancern National Alliance. Statistics. http://www.ovariancancer.org/about-ovarian-cancer/statistics. Accessed Dec. 29, 2013.

- American College of Radiology. ACR Appropriateness Criteria: Acute pelvic pain in the reproductive age group. American College of Radiology website. http://acr.org/~/media/ACR/Documents/ AppCriteria/Diagnostic/AcutePelvicPainReproductiveAgeGroup.pdf. Accessed Dec. 10, 2012.

- Laméris W, van Randen A, van Es HW, et al. Imaging strategies for detection of urgent conditions in patients with acute abdominal pain: Diagnostic accuracy study. BMJ 2009;338:b2431.

- Tayal VS, Bullard M, Swanson DR, et al. ED endovaginal pelvic ultrasound in nonpregnant women with right lower quadrant pain. Am J Emerg Med 2008;26(1):8185.

- Fleischer AC, Cullinan JA, Kepple DM, et al. Conventional and color Doppler transvaginal sonography of pelvic masses: A comparison of relative histologic specificities. J Ultrasound Med 1993;12(12):

705712. - Desai SK, Allahbadia GN, Dalal AK. Ovarian torsion: Diagnosis by color Doppler ultrasonography. Obstet Gynecol 1994;84(4 Pt 2):699701.

- Tepper R, Zalel Y, Goldberger S, et al. Diagnostic value of transvaginal color Doppler flow in ovarian torsion. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 1996;68(1-2):115118.

- Peña JE, Ufberg D, Cooney N, et al. Usefulness of Doppler sonography in the diagnosis of ovarian torsion. Fertil Steril 2000;73(5):10471050.

- Derchi LE, Serafini G, Gandolfo N, et al. Ultrasound in gynecology. Eur Radiol 2001;11(11):21372155.

- Ignacio EA, Hill MC. Ultrasound of the acute female pelvis. Ultrasound Q 2003;19(2):8698, quiz 108110.

- Vandermeer FQ, Wong-You-Cheong JJ. Imaging of acute pelvic pain. Clin Obstet Gynecol 2009;52(1):220.

- Stunell H, Aremu M, Collins D, et al. Assessment of the value of pelvic ultrasonography in pre-menopausal women with right iliac fossa pain. Ir Med J 2008;101(7):216217.

- Asch E, Shah S, Kang T, et al. Use of pelvic computed tomography and sonography in women of reproductive age in the emergency department. J Ultrasound Med 2013;32(7):11811187.

- Gaitini D, Beck-Razi N, Mor-Yosef D, et al. Diagnosing acute appendicitis in adults: Accuracy of color Doppler sonography and MDCT compared with surgery and clinical follow-up. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2008;190(5):13001306.

- Poletti PA, Platon A, De Perrot T, et al. Acute appendicitis: Prospective evaluation of a diagnostic algorithm integrating ultrasound and low-dose CT to reduce the need of standard CT. Eur Radiol 2011;21:25582566.

- Gao Y, Lee K, Camacho M. Utility of pelvic ultrasound following negative abdominal and pelvic CT in the emergency room. Clinical Radiology 2013;68(11):e586e592.

- Shih CH. Effect of emergency physician-performed pelvic sonography on length of stay in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med 1997;29(3):348351, discussion 352.

- Thamburaj R, Sivitz A. Does the use of bedside pelvic ultrasound decrease length of stay in the emergency department? Pediatr Emerg Care 2013;29(1):6770.

- Adhikari S, Blaivas M, Lyon M. Role of bedside transvaginal ultrasonography in the diagnosis of tubo-ovarian abscess in the emergency department. J Emerg Med 2008;34(4):429433.

- Melnick ER, Melnick JR, Nelson BP. Pelvic ultrasound in acute appendicitis.

J Emerg Med 2010;38(2):240242.

Subscribe Now for Access

You have reached your article limit for the month. We hope you found our articles both enjoyable and insightful. For information on new subscriptions, product trials, alternative billing arrangements or group and site discounts please call 800-688-2421. We look forward to having you as a long-term member of the Relias Media community.